Faking Bad WiFi, Growing Xenobots, Drumming to Heartbeats: A Year in Review

If 2020 was unanimously deemed an annus horribilis, for the lack of consensus we may consider 2021 an annus discors, a discordant year. As we end a year that was in ways both more hopeful and exhausting than the one before, Broadcast reflects on the stories we published that attested to the present’s complex uncertainties. From small shifts in perspective to radical, field-transforming discoveries, may these selections provide reflection, guidance, or at the least, a welcome, engrossing distraction.

This year saw the devastating loss of many cultural giants, including the pioneering scientist, artist, and free jazz drummer Milford Graves, who liberated percussion from rigid timekeeping standards. In a wide-spanning and life-affirming conversation between Graves, executive director of the Haitian Cultural Foundation Jean-Daniel Lafontant, and writers Jake Nussbaum and Catherine Despont––which Broadcast republished from The Pioneer Works Journal at the time of Graves's passing in February––Graves recalls when he taught basic drumming at Bennington College. Students from different cultural backgrounds would enroll, lamenting that they didn’t have any rhythm.

“Those kids really believed that!” Graves exclaimed. “So I would record their heart sounds and find all kinds of rhythms. There’s a lot of hidden things in the heart––it’s amazing. It’s like I’m discovering the DNA of heart sounds.”

While it is crucial to honor the dead, these passings also remind us that it is equally important to praise the living, and give our artists their roses while they are alive. One such artist is the psychedelic soul musician Swamp Dogg, who was scheduled to open for Prine before the tour’s COVID’s cancellation. In a studio concert recording of his album “Sorry You Couldn’t Make It,” Swamp Dogg establishes himself as one of the greatest living musicians to grace us today.

Milford Graves at his drum set in his practice pagoda studio.

Photo by Coke Wisdom

Swamp Dogg: Sorry You Couldn't Make It

Photo by David McMurryAs time becomes harder to track, where better to look to than art that plays with the temporal order? In his provocative and at times salacious essay, David Everitt Howe writes on such art, namely the performance duo Gerard & Kelly. For their exhibition CLOCKWORK, they staged an accompanying performance where two dancers executed gestures that alluded to memories:

3 PM…

rushed Italian voices

scouring your neck for the marks of some anonymous other

Fire Island

The performers recited their scores throughout slits of sunlight that came through twelve windows covered with tinted vinyl. This “light show,” Howe writes, indicated more than the chronology of a day or year, but an “abstract map of planetary movement––an unfathomable timeframe stretching millennia, against which our lives are but a blip, if even.”

The conception of time is inextricably tied to the conception of space, a relationship that has forever motivated scientists, like the physicist Roger Penrose. Astrophysicist and Broadcast’s editor-in-chief Janna Levin breaks down the drawing that won Penrose a Nobel prize “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity”:

“ …a star begins to collapse and he draws the lines of the outer atmosphere shrinking as we move up the figure and into the future …even light is driven mercilessly inward as represented by the cones pointing toward the future. Since nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, everything is driven inevitably away from the event horizon deeper into the hole.”

The notion of space connotes both the infinitely vast universe and the everyday sense of moving freely through one's surroundings. The latter concept of space, and how it's structured by race, class, and gender, was the subject of one of Pioneer Works' first exhibitions when we reopened in April: Brand New Heavies, guest-curated by creative powerhouses Racquel Chevremont and Mickalene Thomas and featuring large-scale works by Abigail DeVille, Xaviera Simmons, and Rosa-Johan Uddoh. After a period of caution and seclusion, this exhibition was remarkably the opposite: bold, daring, and large-scale. “Many artists of color, specifically female artists of color, don’t have the same opportunity to create monumental work.” Thomas says in a behind the scenes video. “We are rarely given the opportunity to take up a lot of physical space.”

As we grew further disenchanted with Zoom, artist Sam Lavigne playfully suggests that maybe we don’t have to live like this. Extending the framework of sabotage that the labor leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn defined as “the withdrawal of efficiency,” Lavigne examines what “digital sabotage” may look like. Taking the form of artistic creations that invite destruction, Lavigne’s proposals include Slow Hot Computer (2016), a website that makes your computer run slower and hotter, and Zoom Escaper (2021) which distorts your audio stream on Zoom to feign a spotty internet connection, loud construction, or even nearby hysterical weeping.

The artist and programmer Everest Pipkin turned away from teleconferencing applications and toward the “lush, blocky, user-design nightmare” gaming platform Roblox, which offers a bevy of different genres of games, “from obstacle course (“obby”), disaster survival roleplay, high school, and ~ vibe ~.” Roblox showed that, despite the fact that the internet is over thirty years old, there still exists completely novel ways to interact with each other. Take a safari game that Pipkin played with their friend V:

“V became a zebra, and I was a lioness. We ran around a broad plain populated by other animals, trees in the distance, low clouds overhead, and the buzzing of insects on a two-minute loop.” V was swiftly killed by a cheetah, who announced the fresh meat to the other players in the chat. “Summoned, I did so, and as I ate the still-living digital body of my friend in the company of a stranger in the shape of a wild dog, I thought, ‘Oh. This is special.’”

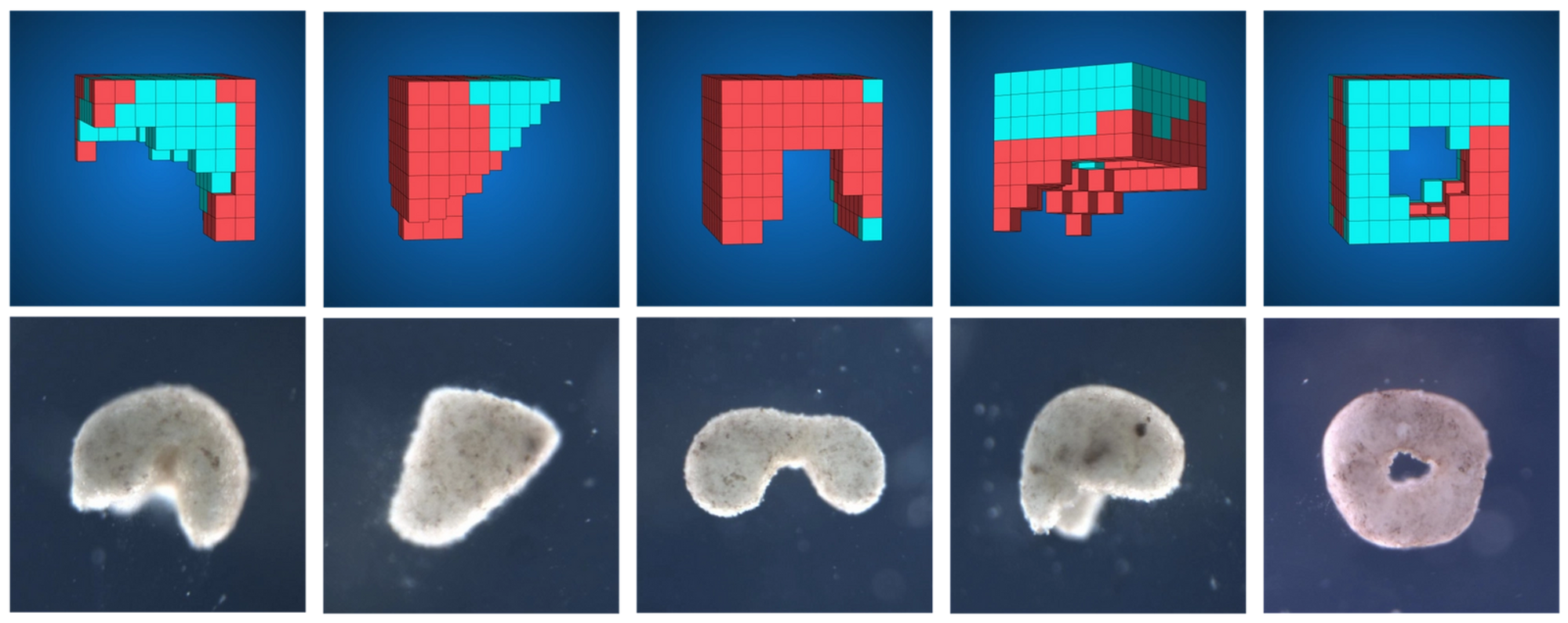

Musician and writer Claire Evans investigates a different type of mirrored life: xenobots, the “world’s first programmable organism,” or, as it was fleetingly considered by scientists, “a living deepfake.” The frog embryo specimen is carefully pipetted into a mold until the cells knit together, forming a tight sphere of living goo. A microsurgeon, using a tiny scalpel and cauterizing iron, physically carves the sphere into shapes suggested by an algorithm. “You watch in awe as the biological Xenobots behave exactly like their silicon counterparts, moving and cooperating… Voila: a computer-designed creature brought to life.” As Evans writes, what this implies is that cognition, then, isn’t binary: “it’s a long continuum that reaches back into evolutionary history, all the way from naked chemical networks to cells, to bacteria, organs, and then whole organisms and humans.”

With the evolution of variants and the current rise of COVID cases, this year is ending as––and for some, even more––difficult than it began. In an elegiac, meditative essay, writer and illustrator J.P. Brammer muses on love, loss, and burrowing in the miracle of a moment amid grief and desolation. Brammer recalls a picturesque road trip with his lover, while his mother’s breast cancer and the romance’s dissolution crept in the shadows.

“Thinking about it just jinxes everything. The sun is so bright here, and the sky is a kind of blue that makes me happy. It’s different from ours back home. We can’t afford to go anywhere, but we’re going somewhere. We’re never going to be together, but we’re together. There’s a wide open road and hours to kill. For a little bit, we can do whatever we want.”

Happy new year, from Broadcast. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast