Healed by the Beat: Milford Graves & Jean-Daniel Lafontant in Conversation

Editor’s Note: To coincide with POTÓPRENS, the large survey exhibition of Haitian contemporary sculpture in 2018, Pioneer Works introduced the polymath Milford Graves to the Vodou priest and teacher Jean-Daniel Lafont and recorded their conversation, which appeared in the fifth issue of The Pioneer Works Journal. Upon his recent passing on February 12th, we’re re-publishing the original discussion here, in text and audio.

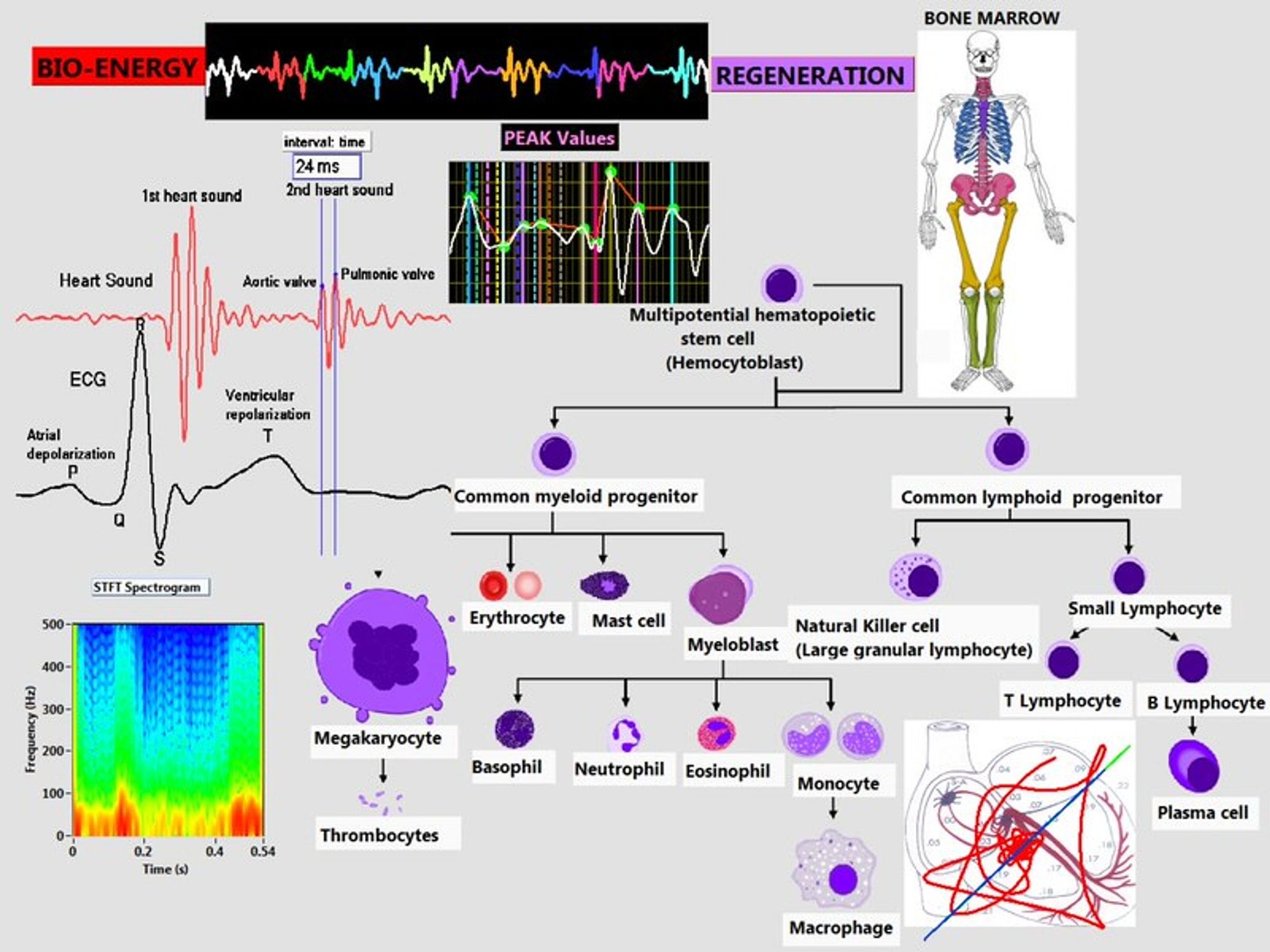

A little over thirty years ago, avant-garde jazz percussionist Milford Graves discovered a record while rooting through the medical section inside of the flagship Barnes & Noble in New York City. He had stumbled upon Normal and Abnormal Heart Beats, a 7” record put out by the facility White Laboratories that listed track titles with medical jargon such as “Typical Systolic Murmur of Dilated Heart and Incompetent Mitral Valve” and “Blowing Diastolic Aortic Area.” Graves heard something else: unorthodox rhythms. During that time, Graves, a practitioner of homeopathic medicine, was a professor of music at Bennington College, where he started recording his students’ heartbeats as a way to research the human proclivity for rhythm. That research led him, along with two embryologists, to look into a theorized beneficiary relationship between stem cell regrowth and vibrational rhythm. Guided by the principle that any mechanical movement creates a percussive noise, Graves has designed software to explore the micro sounds of the tiny cardiac rhythms in between each loud “da-dum” of the pulse.

Musically, his results sound like an internal free jazz of the human body. Medically, Graves is credited for discovering “VHR,” (variable heart rate), a concept about the variety of micro-patterning within our heartbeats that has particular use in the field of embryology. Scientists have begun working with vibrations to stimulate growth in stem cells, and they are working alongside Graves to find how variable rhythms could improve their results.

Haitian Vodou has a rich lexicon of percussive rhythms, and as a houngan (vodou priest) and the executive director of the Haitian Cultural Foundation, Jean-Daniel Lafontant knows them both as a scholar and practitioner. Different spirits or loas require specific rhythms in order to be invited to mount a body, where it can adjust its physicality, including heart rates. Lafontant believes these spirits are capable of making their hosts perform super-human tasks. To Lafontant, the spiritual and communicative power of the drum has historically helped organize the Haitian people to overcome the yoke of French colonization and has continued to draw people out into the streets in solidarity over injustice.

In 2017, Graves and Lafontant met up at the home and garden of Graves in Queens, as lovingly seen in the film Full Mantis, with Jake Nussbaum and Catherine Despont of Pioneer Works to discuss the potential of self-induced healing, the relationship between the heart and the drum, and the instrument as a protest and revolutionary tool.

I had originally thought to turn this conversation toward the multidisciplinary approaches that you both take in your work, but as I was setting up you immediately began to talk about the relationship between drumming and healing. Jean-Daniel, you explained to me how a Vodou priest has to be able to sing, to drum, to build things with their hands, to heal people. You also mentioned the history of Vodou drumming, especially drumming’s effect on the body. And Milford, you take a very similar approach as a healer, drummer, and scientist. When we first met, we spoke about this same topic: how sound waves, the drum, and the membrane play roles in healing. So maybe you each could begin by describing how you developed a healing practice?

1975—I was in the medical section of a Barnes & Noble bookstore and found this recording of pathological heart sounds put out by a pharmaceutical company. My intuition said, “buy this recording.” When I went home and listened to it I could hear traditional African drum rhythms in the heart sounds. I immediately called up all these drummers and told them about what I was hearing. These pathological heart rhythms were similar to the rhythms that a drummer gets into when in a state of possession. Everybody thinks a normal heart should beat like ba-boom, ba-boom, ba-boom, but it might not actually beat like that. When a drummer gets into a state of possession you can hear all kinds of heart rhythms, not just ba-boom, ba- boom, ba-boom. But since no one was recording a drummer’s heart when he or she was playing, no one knew! Now with wireless microphones, or Bluetooth, somebody can be in ritual, and you can pick that stuff up. If you want to know more about the heart, then you gotta know about African drum rhythms, and that includes the diaspora—Afro-Cuban or Haitian drummers who use all their fingers or whole hands—that all counts.

I’m amazed at what you’re saying, and I’m extremely touched for several reasons. The drum is a sacred element of Vodou. I’m not a musician, but as a priest, drumming is a vital part of ritual. The male drummer, an ountògi, has to go through a process of initiation to be able to beat the drums. To confirm what you’re saying, Vodou has 21 nations and 421 families of spirits. They all have their own rhythms, their own rights, and their own ways of playing the drums. The further you go into the mountain, the higher and faster the tempo. The beat of the drum allows people to transform themselves from humans to beings of a different nature—part human, part something else. It gives us stamina. People can walk far distances riding on the rhythm, the constant rhythm, of the drum.

Very recently, I was speaking to a friend of mine, a very sophisticated lady of Haitian descent, which means she has Vodou in her DNA. She told me that one day a rara band procession passed near where she was working at the Little Haiti Cultural Center in Miami. She started following them and ended up walking for several kilometers, not realizing how far she was walking or where she was going. It was only after the rara band stopped playing that she realized how far she had gone: she was in a no man’s land neighborhood. She was so scared that she asked two guys from the rara band to take her back to her car. She didn’t realize she had been hypnotized by the sound of the drums until they had stopped.

The drum is for us a divine instrument, not just for Africans, but for many indigenous people as well. It was the first instrument. And what you’re saying is correct: the drum is actually the heart. And it can transform men into anything, good or bad. It can heal. It can cure. It can make you crazy. It can increase your sex drive. I am thinking right now of particular beatings of drums and feeling almost aroused. Because a drummer can transform people, a drummer is, in a sense, a god. So you are a god, Milford. You are a living god because you are a drummer and you can transform people. You are a creator. So this is a point that I wanted to make.

One thing I want to add is that all human beings have a very sim- ilar basic rhythmic pattern. I learned this when I started recording heart sounds up at Bennington College, where I taught for thirty-nine years. It was a great experience—all these kids from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds wanted to take my class and learn basic drumming. I’d ask, “So why do you want to learn to drum?” And they’d tell me that they wanted to learn rhythm because they didn’t have any. I was like, “This is deep, man.” People used to say that white drummers had no rhythm. That they knew harmony and melody, but they don’t have the rhythm. Those kids really believed that! So I would record their heart sounds and find all kinds of rhythms. There’s a lot of hidden things in the heart—it’s amazing. It’s like I’m discovering the DNA of heart sounds.

I once had a student, a twenty-eight-year-old white American woman who had spent some time in Ghana. I recorded her heartbeats and trans- formed them into equivalent melodies and rhythms. And I told her, “My gracious, this is some heavy-duty, beautiful stuff you got coming out of you.” When she heard it, it blew her away. Because she recognized these 12/8 patterns, ga ding gong,ga ding gong, and I said, “That’s in you!” I don’t care where you come from, man. I’ve had people of European ancestry, African, Asian, everybody. We all got these basic patterns.

One of the things I’ve noticed about Vodou drumming and about Haitian people was that you had a better sense of your vibration, that the conditions that you were put under in order to survive caused you to go into another kind of vibrational mode. Spiritually, man, you gotta vibrate. Just the fact if you want to live, that causes you to vibrate. And so that instinct thrived in the Americas more than it did in Europe. They got too intellectual in Europe—they started worrying too much about machines and industry and forgot about their soul, man. So they didn’t vibrate the same kind of way, a rhythmic way, that the African diaspora did, especially the Haitians. Vibration was a form of healing.

CATHERINE DESPONT

Can you both maybe talk about how you understand health? Because I think there is all this misunderstanding of the body—when you’re listening to things, you learn to listen to the body too—and I wonder if you could talk about that part of the process—how the understanding of the body is connected. For people in Western cultures things like rhythm, health, mind, and body are separate.

I was sick from abusing alcohol so early in my life. I first got drunk when I was eight years old. I was curious about this bottle of fluid that my father was drinking. He thought he’d hidden it from me, but I knew where it was, and I drank it, and man, I got drunk. After that, I started hanging out with older guys and drinking a lot of cheap wine and eating greasy food on the street corner. By the time I was about eighteen, I’d messed up my whole abdominal system. I was urinating blood, I had no bowel movements or feces. It was excruciating pain. So I had to stop drinking and start healing myself. I remembered that my grandfather was always suggesting herbal remedies. I hadn’t paid him much attention when I was a young man, but after I got sick I went back into the literature and found all the herbs and remedies that my grandfather had mentioned. I started drinking raw cabbage and potato juice, and I became a vegetarian. That’s how I started healing myself. And a lot of people who knew me kept telling me how great I was looking, that I was “walking sideways,” you know, ribs showing and everything. Then people started asking me to help them heal. I’d tell them to take this herb and do this and do that. And that’s how basically I got into healing, you know? By being sick!

For me it was the same. When I was, I think, twenty-five, I’d become very sick. I was living in New York at the time, and I went to see a doctor in Queens. And he told me that I had a disease that appeared to be similar to AIDS. He wasn’t exactly sure what it was, but seeing the state that I was in, he did not think that I was going to live a very long time. So I panicked and immediately went on a coconut water diet—solely coconut water. I didn’t know if it had helped, but after a month, I started eating again. A few months later I went back to see the doctor, and he didn’t recognize me. I figure maybe he thought I was another black man, because some people think all black men look alike. But after speaking to him, I realized that he did not recognize me because my appearance had changed. He looked through my files and he told me that it was impossible that it was me because the person that he saw before should have been dead by that point.

So my learning of healing began with my own sickness. I did many things like learning about herbs. I even became a vegetarian for a while, maybe four years. I stopped, which I really regret. I should have remained a vegetarian my entire life.

I think the worst thing you can do to somebody is stamp a time on when they’re going to die. “You’ve got six months to live.” Doctors will say things like that, but medicine is only one part of it. If people’s spirits are destroyed, the medicine’s not going to do any good. And there are some healers who even use the power of the placebo effect to help people. I mean, what’s wrong with a placebo? If you can get somebody to really believe in it, they’ll be their own internal pharmacy. Nature makes everything that we need, you know? You drank coconut water because you believed it would heal you. Otherwise, it must have been some good coconut water.

Some very good coconut water. To me, the body is constituted of three main aspects: the physical, the mental, and the spiritual. It’s kind of a triangle, and each tip has to be taken care of. Treating one aspect of the body without treating the other could provoke instability, which will create, I believe, a bigger disaster. To give you an example: A friend of mine wrote a book about how people are given treatment in different parts of the world. In one section, he wrote about how two Haitian men with AIDS, at the same stage of infection, were given different treatments. One of them was treated by conventional medicine and the other by traditional medicine. The man who was treated with traditional medicine saw a priest who told him that he had received a kind of spiritual disease, and that he should not have sex with people because that disease could be transmitted through physical means. But because the priest had told him this, the community in which he was living accepted him, and that man lived for many years.

The other man, however, was treated by conventional doctors who told the people in his community that he had AIDS and how to treat him. But they did not accept him back and instead banished him. He had to live in different places, and died much earlier than the other man. So quite often the stress of not being in a social environment, of not being around other people, makes you very sick. We are like ants. We are creatures of community. And this is one thing that’s being destroyed today.

We have to take the total of human consciousness in the world and see how we can work as one big unit. Scientists aren’t going to do it. Non-science people aren’t going to do it, They’re both missing things and need to work together. That’s what I’m seeing, you know? I’ve actually been collaborating with this Italian microbiologist named Carlo Ventura and his team to develop non-embryonic stem cells. He has been trying to prompt stem cell growth by using different frequencies, so when he found out about my work with heart sounds, he got in touch. Now I supply all the frequencies from the heart sounds I’ve recorded. What we’re doing is something that none of us thought could be done, you know? But it’s collaboration— without them, I don’t know if I would have found out about certain things, and maybe without me, they wouldn’t have found out about certain things. All our names are on the Google patent we have on the project. These are legitimate scientists; Carlos is both a microbiologist and a cardiologist. So they’re world class, you know?

This is great. I also don’t think we should separate conventional science from traditional science.

It’s a new kind of science so it’ll need a new name.

Yes, yes, I agree.

There has to be a new way, a new philosophy. There has to be a new way of mathematics, for instance, because mathematics is nothing but symbology for a concept. And when you try to plot out motion with mathematics, you create a veve. I always tell people this, whether they want to accept it or not. That’s a Vodou symbol.

I completely agree.

But if you want to interpret further, which is what some intellectuals do, you can go down into the nervous system, which is divided between the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems—a yin and a yang. We observe nature in one way and science uses a different way. For instance, you can observe electrons through a machine, but you can also observe electrons in humans when you see someone possessed by rhythm. We’ve got to study the movement of those electrons as well. So I’m telling these scientists that before they go into their big chambers and oscillating machines, man, they need to go into possession through drumming. And after they encounter possession, then maybe go and watch that electron—they may discover something new about it. But if they are all conventional science and no traditional spirit, then that’s not going to happen.

Have scientists tried this before?

No.

Have they practiced any drumming?

See, that’s what I do. That’s my research. I go toward tradition and I take everything from tradition. When I listen to a heart sound or a heart rhythm, I’m thinking of all the rhythms I’m doing and I try to see if I can hear it in the heart. But I’m also coming from a place of possession, which is different than looking at something under a microscope and trying to analyze it. I’ve already got my spirit up. When I hear it, I say, “Oh, that’s what I’m hearing. Well, if I do this and do that what will come out?” That’s a whole different approach. Scientists will probably be doing this soon, because I’ve been talking about it for years. They could be doing it now, but if so, they’re very quiet about it.

That’s what has happened. They’ve been looking for these secrets all over the place.

I know.

They’ve been looking for ages.

And they don’t say nothing.

And I think that, well, they would never say anything because they don’t want you to know that they took it from you.

That’s right. They may be right in the house, man. Incense and ritual going on. Then they publish a paper claiming they just figured out a new formula, you know what I mean? But they ain’t going to acknowledge that traditional stuff, no. They aren’t going to share that.

No, they aren’t going to share it. But they’ve been researching a lot. And I think that many of these discoveries are made when they turn to tradition.

Oh yes, no two ways about it. People are starting to talk about it more.

Even the veve that you were talking about—we don’t know what these signs are, but we know what these signs do. It’s the same way I don’t know how to play the drum, but I know what a drum does to me.

Yeah, but I heard you scat out a drum rhythm with your voice that was pretty slick, man.

Well, I know what it does to me.

But you did something, man. And to be a drummer, the first thing you’ve got to do is sing what you play.

I’m not a drummer.

Yeah, but you can sing rhythms.

Well...

Maybe your hands ain’t playing what you singing, but some guys who play with their hands can’t sing what they are doing. What you just did—they can’t do that.

There is something we can’t not talk about since you are both sitting here together. I was wondering if could you tell the story, as you see it, of the role that drumming played in the Haitian Revolution and the civil rights movement?

Before the revolution, there were and still are multiple Vodou beliefs in Haiti. The Revolution was born at the Bois Caïman ceremony in August 1791, when the spirit nations and families of Vodou came together as a congress—and I call it a congress—to unite as one in its diversity in order to fight the oppressor. During that congress, Vodou drumming uplifted the people, changing their physiological bodies into supermen. That was how the Haitian slaves, what we call the Indigenous Army, those maroons, those barefoot men, defeated the mightiest power in the world at that time, the army of Napoleon Bonaparte. Only the drums and rituals of Vodou could give them that power to defeat the Bonaparte army. Only them.

During the ’60s, I was often called to play at political rallies, particularly rallies that dealt with civil rights-like nationalist movements. For example, in 1965, there was a parade in Harlem that took place when the Black Arts Theater opened up. People were waving both the Black Arts flag and the American flag. Amiri Baraka and a few people from the Black Arts movement were up in front leading the parade. A police car followed it from the back. I had a little drum tied around me and was part of a twelve-man band with Sun Ra’s band right behind us. People were hanging out of their windows and on the roof. I’m going from one side of the street to the other, playing my drum. I knew there were certain rhythms I had to play, rhythms that came from the culture of the time. During the civil rights movement, I wasn’t playing to entertain. These rhythms were different. The energy that was in there was of a positive anger. I was angry at the situation that was going on in this country—all the racism and everything that was going on. I was just sick and tired of it. You know? I had a lot of conviction when I hit that instrument. It was like freedom.

I think we need more drums. Like now, in Haiti, there is a similar occupation by people who think money is god. So people take to the streets, and when they do, the drum is always there. If I do Vodou ceremonies, sometimes we play for seven days, nonstop. The drums may stop at some point, but for seven days afterward I don’t sleep, and it is because the drumming is still with me. And now I see the power of the drum within the Black Lives Matter movement. I like it. If the drum is not played with your hands or fingers then the drum has to be played inside your thoracic cavity, inside your heart. The drum carries people through hours and hours of marching. That is why every revolution needs a drum.

Editor's Note: Milford Graves passed away shortly after the closing of a comprehensive exhibition in ICA Philadelphia where archival footage and music was mixed in with new kinetic sculptures that Graves was making combining drawing with wires, medical charts, screens and skeletons. In conjunction with that show, Jake Nussbaum conducted a Zoom conversation about the show with drummers Will Calhoun and Susie Ibarra. Milford Graves enters the conversation at minute 54:00 with a lot to say. Graves would pass away just four days later, leaving this video as his last public appearance and lesson.

Subscribe to Broadcast