An Index of Indexes

Our ever-evolving and impossible-to-name ecosystem of “arts” and “technology” has many initiatives, texts, and organizations that attempt to define these terms and their intersections, but only a few highlight the interlocking networks of people that animate these spaces. That's what excites me about Mindy Seu's work. She's not particularly interested in domain definition but instead committed to revealing a more complex story of multiplicity, transformation, slippage, and deviation. I first met Mindy Seu in 2018 when I was part of Refresh, a collective of new media artists working across science and technology. At that time, Mindy was working on early iterations of the Cyberfeminism Index––a catalog of online activism and net art from 1991–2020—and she shared thinking and research for the project. Our touchpoints quickly went from hallway chats at events and programs to check-in calls about our work to an invitation to Refresh to contribute to the Index. In the four years since, I’ve found it a true honor to witness Mindy’s quiet and big work of gathering Us and reflecting back to Us a continuum of thinking that exists not in a straight line, but instead with many beautiful divergences, fractions, and cycles.

Collecting is a practice rooted in care and commitment. It’s very clear that Mindy cares and is committed to chasing and weaving the threads. On the occasion of Cyberfeminism Index’s book launch at New Museum, we got together to discuss this vibrant and sprawling project.

Thank you for seeing, finding, and bringing these histories together. How did this book come to be? How did you begin exploring cyberfeminist histories?

We know so many people in our communities pushing the bounds of tech, who are thinking about critical technologies and its implications on our society. In spite of its problems, I’ve been inspired by the Whole Earth Catalog, as well as the New Women’s Survival Catalog, which was billed as “the feminist Whole Earth Catalog.” This subjective but comprehensive compendium of second-wave feminism in the U.S. doesn’t nearly receive the type of attention that the Whole Earth Catalog does. I wanted to see something similar that shows what our friends are working on now, and it was really difficult to find. So I just started making lists as a resource guide for myself. Once I shared it with others, I realized that this actually seems like a valuable resource for specialists and newcomers.

It’s so beautiful to have a repository like this because one of the challenges is that we’re not as connected as one might think we are.

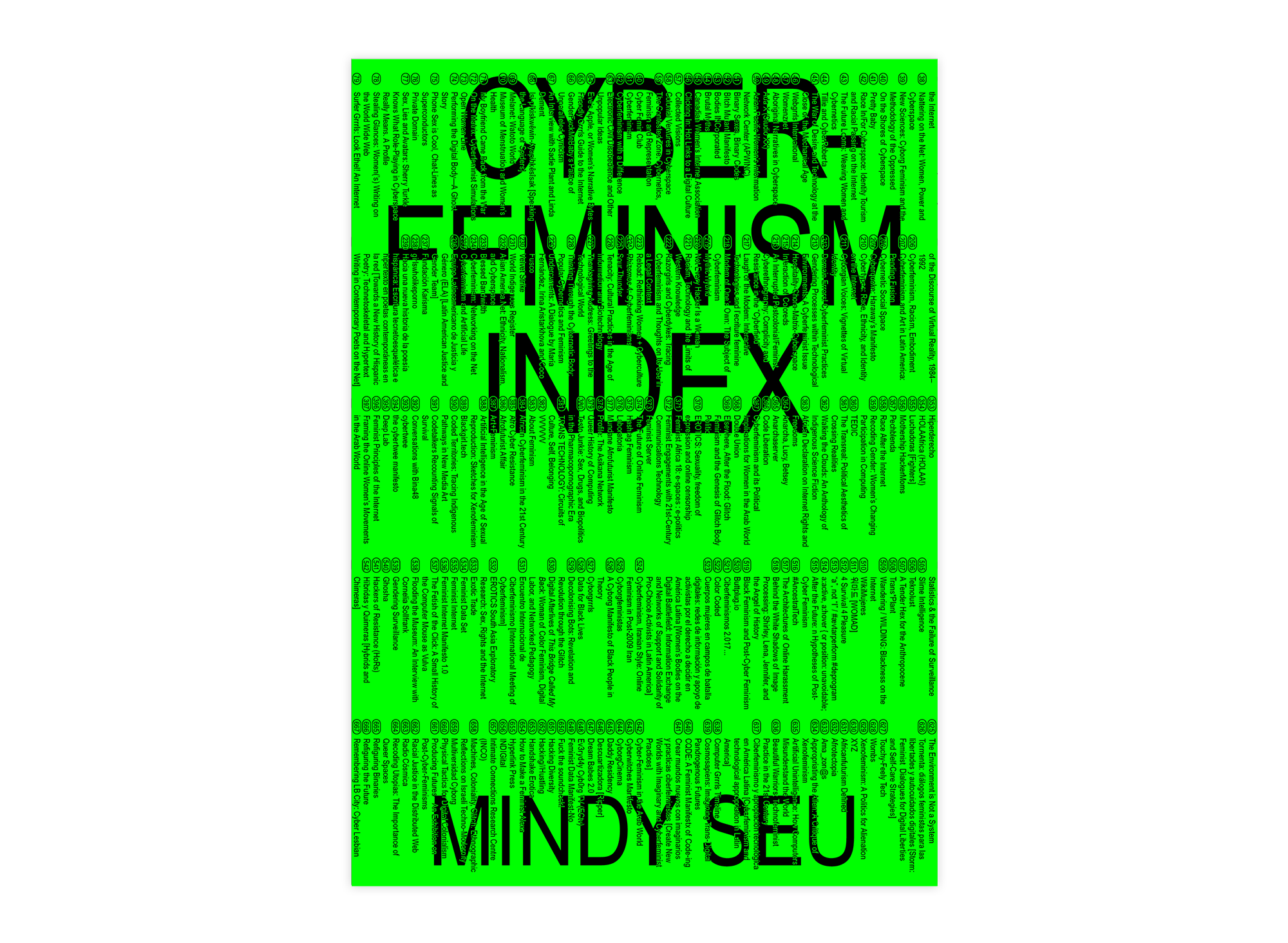

Yes, showing this interconnectedness of practices was the goal: a subjective, living, and ever-evolving collection. The Cyberfeminism Index started off as an open-access spreadsheet. I added the first several hundred, and then people added hundreds more, and it continues to be crowd-sourced. We got the bulk of submissions outside of our direct community. It was heartwarming to see familiar names submitting things that are more historical or more contemporary, even things that I might not have personally identified as Cyberfeminism. But that’s what’s great about this term; it’s so malleable and porous. The book has 703 entries. The website has more.

In your intro for the book, you write that “Cyberfeminism is a mutating word with a nebulous history. Its evolution is less a single root system with multiple branches than a network of entangled rhizomes, constantly and multidirectionally moving.” It’s clear that cyberfeminism has never been faithful to any origin, and is non-authorial. So what kind of parameters did you set in your indexing process? Or specifically, why does the chronology start at 1991?

1991 is the year the term “cyberfeminism” came into prominence, from two distinct groups: media theorist Sadie Plant in the UK and the collective VNS Matrix in Australia. Coming from cybernetics, “cyber” gets affixed to cyberspace and texts like William Gibson’s Neuromancer. Even if it predicted the sensory network computing landscapes that we’re now enmeshed in, it was also characterized by the male gaze, filled with fembots and cyberbabes. So when “cyber” was affixed to feminism in 1991, it felt like a provocation, asking marginalized communities to consider what their version of technoutopia might be.

What throughlines stood out to you when you were organizing the materials? What shifts or fractions did you notice moving through time?

This is a tricky question, because it’s not only about time, but also place. The other timelines of “women and media” or “gendered technology” that I came across primarily focused on the United States, Australia, and Europe. When I started doing research, I found hackfeministas in Latin America, Netfemis in Korea, and complementary movements happening simultaneously, like Womxnist Afrofuturism, Xenofeminism, and more. I put these under the imperfect umbrella of cyberfeminism.

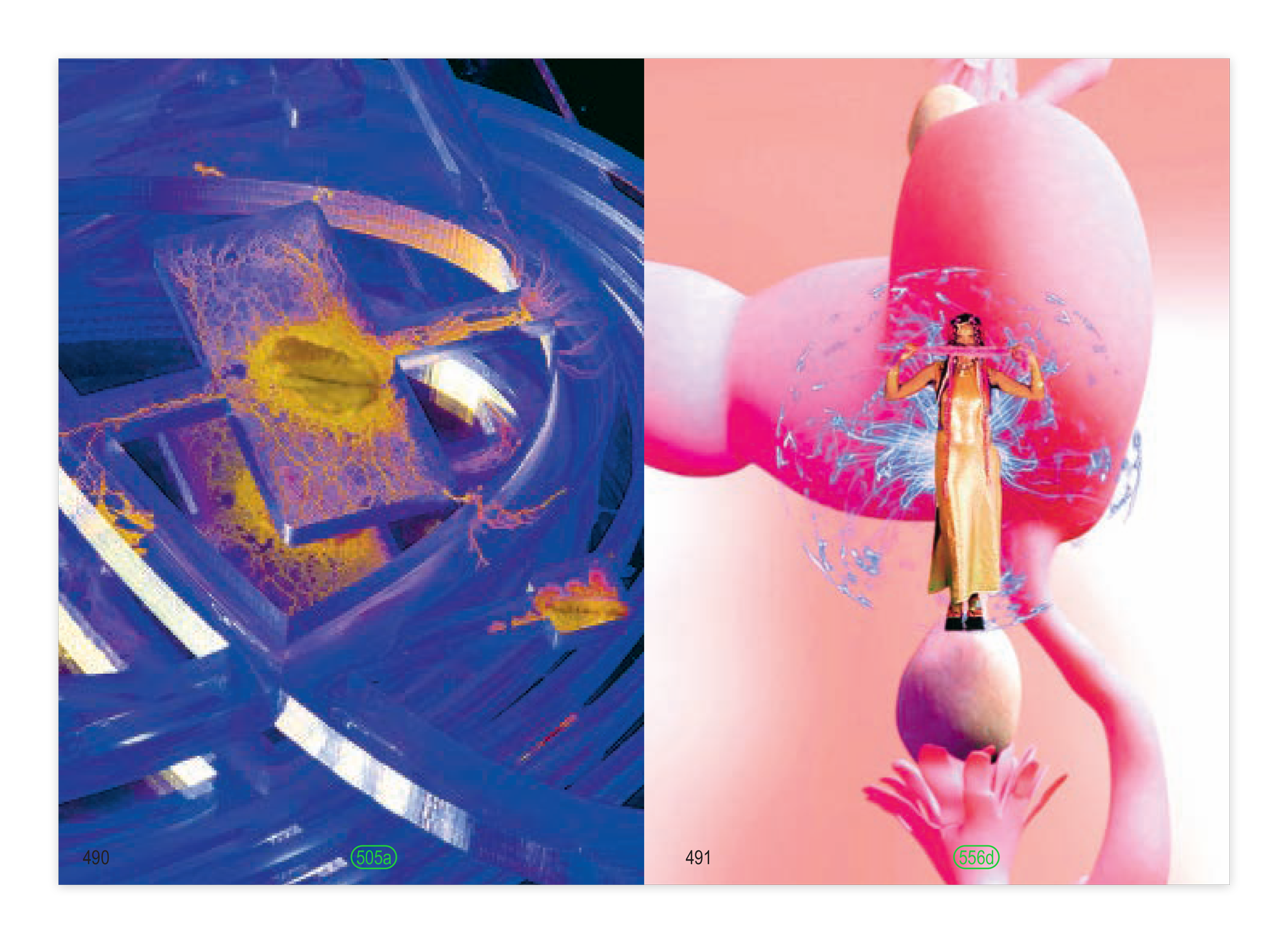

We’re able to trace this between the blurry bounds of Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Web3. In Web 1.0, people built experimental online microsites, from hypertext fiction like Gita Hashemi’s shifting shadow solitude (1999), instructions for getting online like FLAME/FLAMME: Sisters On-Line (1994) , and webrings to create community online like WWWomen WebRing (1996) . Early Web 2.0 also created networked spaces like FemTechNet (2012). Unfortunately, Web 2.0 as we know it is shaped by the rise of platform oligopolies, templates, and a growing disillusionment with the internet’s potential. From this, we see the rise of hashtag activism, such as MEXA! Feminist Online Takeover (2017). It moves outside of the screen, like 3D-printed speculums by Gynepunk (2014) and Mary Maggic’s hormone hacking Open Source Estrogen (2015). Then as we veer towards Web3, we start to see works that deal with the internet’s impact on ecology and the economy, revealing its relationship to currency. Sex workers being some of the first early adopters of blockchain because their work was villainized and avoided by standard payment processors, birthing cryptocurrencies like Titcoin (2014).

Can you talk about the iterations of this project as a book and a website?

I’ve always been interested in the complementary form of books and websites. People think books are fixed, while websites are interactive, but they are both quite interactive with learned interfaces. In a book you have a cover, a table of contents, foreword, etcetera. Websites have similar conventions, so my collaborators Angeline Meitzler and Laura Combs were both drawing attention to and trying to break these standards. We also worked with Lily Healey to import this into InDesign, so they flow between each other.

You’ve referred to it as a “hyperlinked network journey.” The design of the book demands a playful exploration.

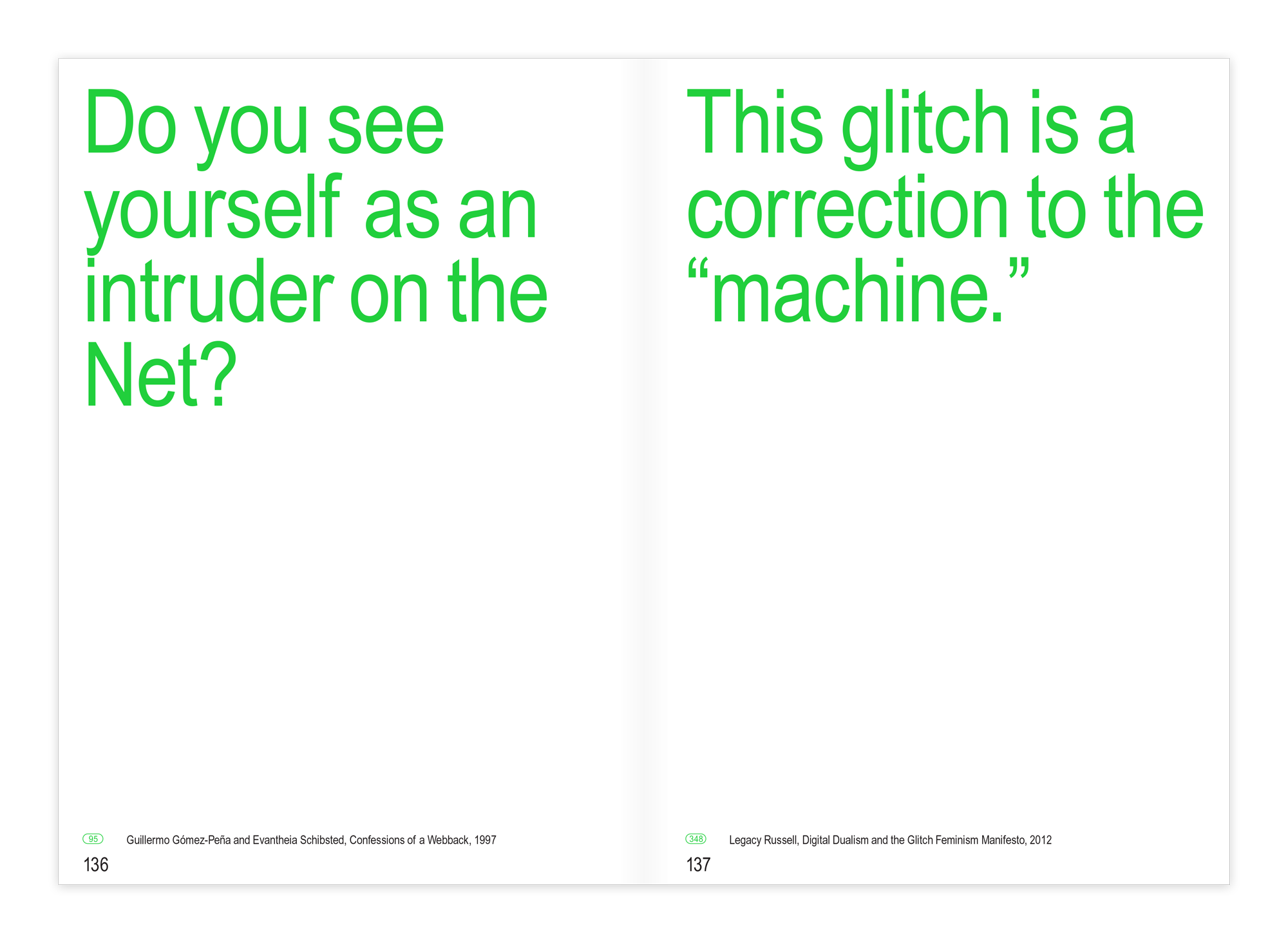

The cross-references are a big part of it. In the history of print, the idea of a hyperlink occurred long before what we think of as a digital hyperlink, in forms such as bibliographies, indexes, and footnotes. Hyperlinks are ways of juxtaposing or complementing ideas. Sometimes it feels like it’s jumping to a related keyword, while other times it jumps to an entry with an opposing idea.

The book is also an index of indexes, similar to an encyclopedia rather than an essay anthology. If someone gives you an encyclopedic volume, you don’t need to read in a linear fashion from the beginning. You open it, randomly find a section, and then associative trails emerge. We also invited artists and collectives to curate their own collections, as various entry points into the book, as a mirror of their practices.

What are some notable examples from the book?

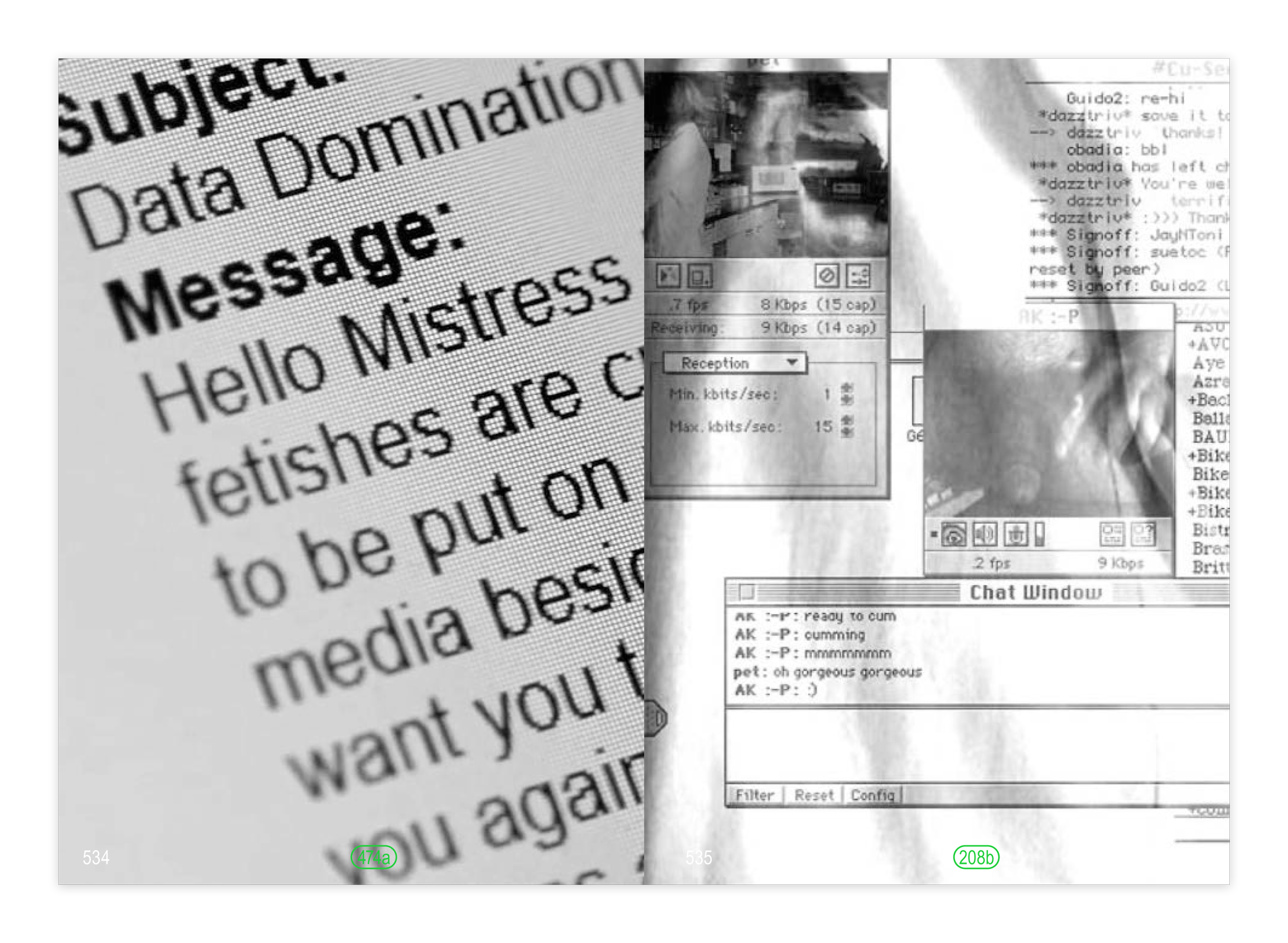

Data Domination is fascinating. It’s a subset of BDSM under the umbrella of tech domination—so it’s not necessarily about camming or nudity. The sub gives remote access controls to the dom, relinquishing power over your machine, accounts, and data.

It makes me think about how sex workers are early adopters of the internet and technology tools and platforms who really give frame and shape to new modes of engagement.

Absolutely. It makes you question our common understanding of sex and its relationship to technology. The artist and educator Melanie Hoff describes sex as “the world our desires produce,” which can be physical, remote, or a psychological power play. Nahee Kim’s project is also related. She makes work that questions the family structure and her own sexuality. In her piece Daddy Residency (2019), she takes applications for “daddies” so she can have a variety of companions for her artificially-inseminated child.

There’s also this early 90s collective called FLAMME. It was an early African network that formed around the fifth Regional Conference on Women in Dakar in 1994 which was focused on getting women online and learning information technology. From Latin America, one of my favorite artists is Klau Kinky, who now goes by Klau Chinche. They made this powerful net art piece called Anarcha, Lucy, Betsey (2013), which interrogates body colonization by revealing the stories of the three enslaved women who were used for gynecological experiments by Dr. Skene. Even now, in our bodies, the gland that becomes engorged during orgasm is called the Skene’s Gland. In Anarcha, Lucy, Betsey, Chinche demands that this be renamed as Anarcha’s Gland.

If you did a part two, which I know is a daunting thought since part one just came out, what would you focus on and include in a second iteration?

Beyond a second iteration, I’m thinking about how this project can continue to create publics and modes of discourse. I’m thinking about complements that feel more rooted in practice than theory. And while there are plenty of examples of practice in this book, the form of the book itself is what Judy Malloy calls “YACK / HACK”—YACK is discourse whereas HACK is practice. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast