Kameelah Janan Rasheed Wants to Name Names

Kameelah Janan Rasheed at Pioneer Works, 2018.

Photo: Walter WlodarczykAs a writer, I've never thought of myself as an artist. Writing is the least sensuous of all the arts, more readily considered a vocation for the geek in the corner: there is no smell of paint in the air or charcoal staining hands, no sound of feet tapping or bodies landing. The outcome is artistic, but the production is not—or so I thought. Kameelah Janan Rasheed's work—rooted in a lifelong ritual of note-taking and archiving, of collection and commitment—is writing as high art, the mastery of using language. As a tool, words are as sharp as any precision knife, as heavy as any brick.

Kameelah's lyrical and associative work defies category, a melange of text and portraiture and drawings and paintings and conversations and certificates. Words spew and stick and float, taking on lives of their own, which goes back to how she arbitrated her practice in the first place: annotations, doing what you can in the margins, asserting one's own space. "When I went to make art, I didn't think about it as art, I thought it was how everyone reads. Aren’t people annotating up and down? Isn’t everyone returning to the same sheet of paper and just writing on top?" With Kameelah, writing is not solely a pursuit, but rather laid plain in all of its multitudinuous-ness: it unlocks, it obscures, it shines, it asks, it sings, it tears, it complements, it answers.

I love that your website’s biography starts in 1991…“My name is Kameelah Rasheed. I am seven years old and go to Flood School.” It makes me feel like you've always taken yourself seriously. Does that feel true?

Yes, it does. My mom would say that even before I could produce language, I was talking. I talk a lot. I always had something to say, and I think I took myself seriously because my parents took me so seriously. They indulged every single curiosity. They never made me feel weird, even when peers did. I recall applying to a Catholic school when I was 13. It was the only school I applied to. I was so hyped. I told my mom, "If I don't get in, I'm not going to high school." When I did get in, I remember my parents said, "Whatever you want to do is on you." They always treated me with a sense of agency, like I had the ability to make sound decisions. And if I made an unsound decision, there was a space to unfold and talk about it. I don’t want to say I had intellectual confidence—because it wasn’t about smarts or intelligence—but I figured out early on that the way I was processing the world needed to be protected. And so I had to take that seriously.

There's nothing I love more than weird Black girls. This reminds me of a story I wrote a few years ago about Whoopi Goldberg. She described something similar, where at one point in her early childhood, her mom sat her down and said, "People are not always going to get your whole thing. You're going to encounter a lot of people who just don't understand it. So you should just make it up, stick to what you want.” That's that access to weirdness. That's why she is the way she is. What do you think about how your parents allowed you to be yourself, and in a broader sense, how your family impacted you as a worker and as an artist?

We didn't watch a lot of TV or listen to a lot of music for the first decade of my life. But we did listen to Stevie Wonder, Babyface, and Gil Scott-Heron. It was just what was on rotation. Islamic nursery rhymes, too. My dad had like 40,000 jobs, one of which was a pharmacy technician. But he threw newspapers in the morning before he went to the hospital. At night, he worked as a cashier at the 7-Eleven. He also sold skincare on the side and worked as an on-call locksmith. Our house was filled with random papers. Newspapers, photocopies. It was a beautiful mess of language. We were also in Silicon Valley, so my brothers and I were on computers very early. I was coding when I was 12 or 13 at Plugged-In. I lived in a very language-heavy, text-infused household. When I decided I wanted to make art formally, I just went to what was natural. Language is the thing that I do. I don't really draw and I don't really paint, but me and words are tight.

A decade and a half ago, I found this maroon binder from my dad. It was all his Islamic studies and Arabic notes from the ’80s, when he was in pharmacy school. He had photocopied and annotated different verses, which he would collage. I brought it back with me to New York because I was afraid my parents would lose it. I gave a talk at Brown once and somebody asked, "To what extent does your father influence your practice?" I didn’t know where that question was coming from, but when she told me to go back a few slides to my dad’s notes, I realized that the way I approach language, the way I approach writing, and reading, is very inflected by his collages and annotations—the way he pulls in all these different, very vernacular approaches to language. When I went to make art, I didn't think about it as art; I thought I was just reading how everyone reads. Aren’t people annotating up and down? Isn’t everyone returning to the same sheet of paper and just writing on top? Aren’t we all doing this? Apparently not. But for me it felt very, very natural. It was in my face all of my life.

Father’s Notes, 1990s.

Father's Notes, 1990s.

Courtesy of the Rasheed Family ArchiveI’m struck by how much of your archival work you've held onto—your early work, the first books that you authored. Who made the decision to hold onto those, and how do they affect your thinking about archiving and legacy and your own work’s future, especially now that you're working much more with computers?

When I was 12, we were forcefully evicted from our house, and in the process of moving we just lost stuff, because there’s only so much you can take with you. Anything that survived was a little miracle to me. When my mom was cleaning out the garage of the house they're in now, a decade ago, she found some of my books I wrote and published when I was in elementary school. I was expecting them to be mildewed and messed up, but they were in pristine condition. That, again, felt very magical to me. Archiving has been a very intentional act of, “I'm going to save this, I'm going to save that." But there's a chance-based element to it as well. In thinking about Black folks, we save everything. Report cards, receipts. I found my grandmother's ledger from when they bought their house in South Central, the first payment they made, and then every payment that they made after that. When I think about my family on both sides, there’s this intense relationship to documentation, because there was a sense that no one else was going to do that for them. No one cared about some Black lady who migrated from Arkansas to California; no one cared, so she had to do it for herself. Now, when I approach archiving, I'm trying to think about the ethics of not only what's collected, but also who gets to access it.

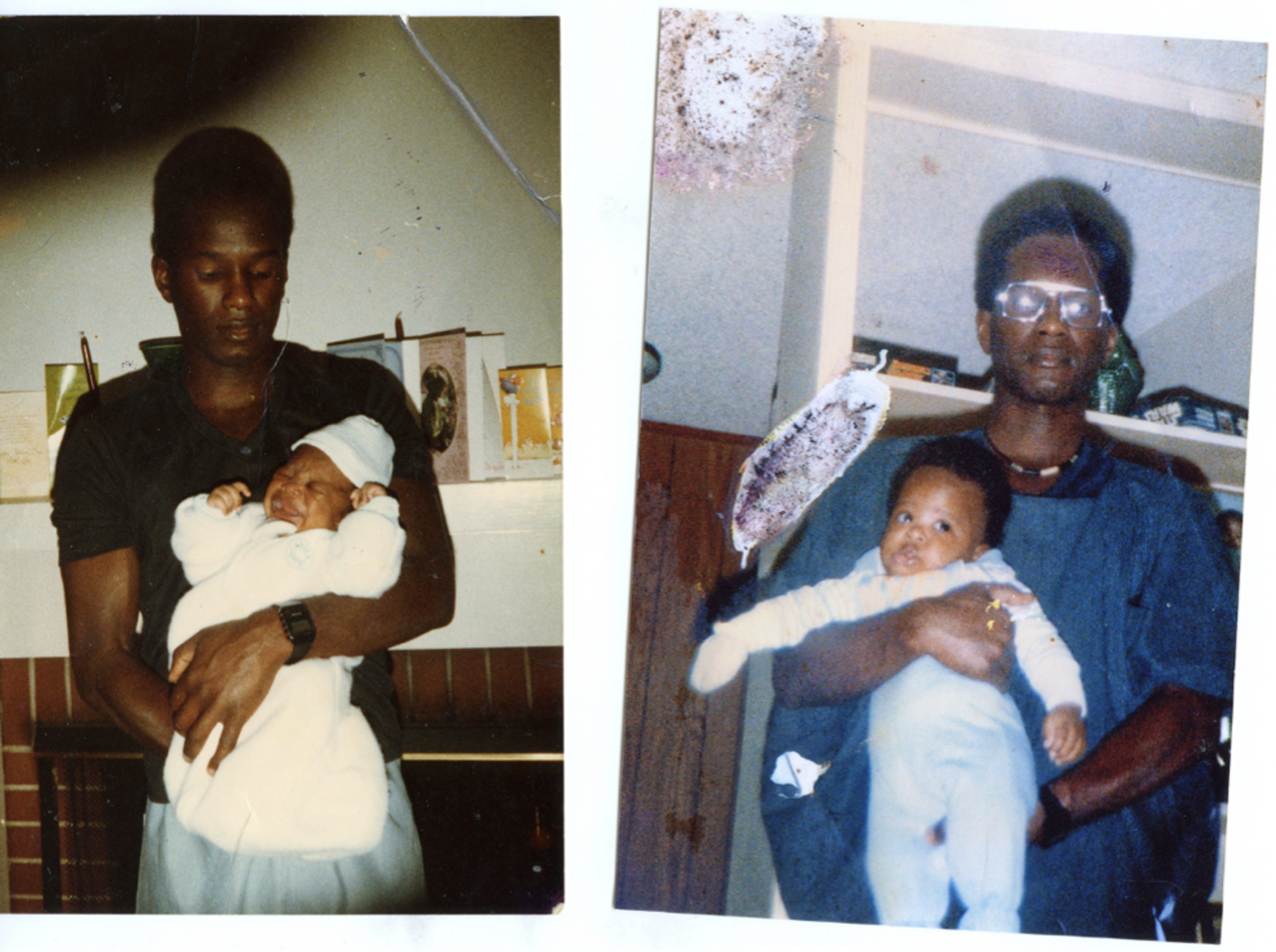

Father, 1983/4.

Courtesy of the Rasheed Family ArchiveI'm working on this project now, Black Orbits, for which I purchase photographs of Black life from yard sales, estate sales, eBay. I had lost pictures of my family, so I was looking for photos of other Black families that reminded me of ones that we didn't have anymore. And it just became this mass collection of over 4,000 images. I was going to put them all online, until I became haunted by the question of, what if the person photographed doesn't want people to see them in this context? I'm working with a web designer now to create an archive that thinks about access. Instead of simply Googling for a picture, you have to register for a library card. You have to answer a couple of questions that center and ground you. Then you get to see the images, but you can't take screenshots of them and you can't copy them. And then they're out of circulation after 30 days. This project has taken me 12 years to realize, because I was trying to build an archive without replicating the violence of Black material culture being circulated as a commodity.

I've been contacting people on Ancestry.com for a personal genealogy project, to find the family that owned my daddy's family. They had big plantations in the Montpelier, Maryland area. I've been contacting these white ladies, saying, "Hey, we share a family tree. I don't need anything from you. I'm just trying to see if y'all got a name, because my ancestor is just listed as an unknown Black woman without record.” These women have read my messages and have not responded. I’ll be in Maryland soon to look at records, and I want them to know that I'm coming for y'all. And I don't even want anything; I just want them to tell me this lady's name. I know that maybe feels like a silly thing, but I just want to know her damn name.

No, it's not silly at all. You are getting acknowledgement of this person's existence, of this past, of this everything. And the craziest thing of all is when white people get all quiet and secretive about the evils of slavery. I hate it. We know so much about the transatlantic slave trade because white people were taking notes. They were writing it in their diaries. They were bragging about all the shit they were doing.

Y’all were trading tips. You made a whole book. I flipped through this book, about the Snowdens, and they’ve said nothing about slavery yet. I got through the first couple of pages, and y'all talking about iron, y'all talking about George Washington, with no mention of slavery. Who do you think was working at the iron mills? It wasn't y'all.

How were these people in the same circles as George Washington? Through their wealth. Where did their wealth come from?

From iron, Jazmine. Iron.

Yes. The iron that just rose up in their backyards, and they just...

Exactly. Who had corn stocks? Did they go and harvest it themselves?

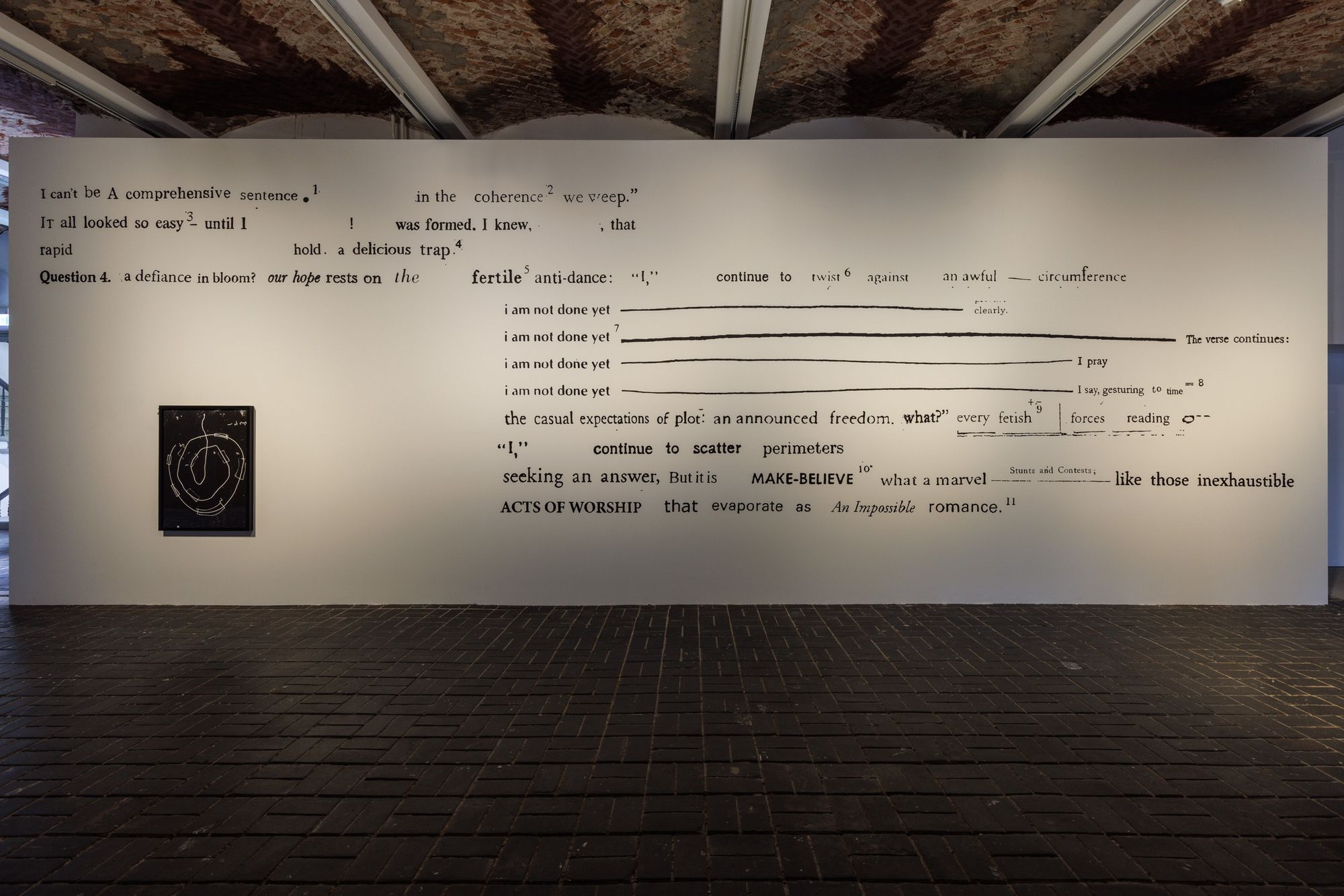

Installation view of Kameelah Janan Rasheed, i want to climb inside every word and lick the salty neck of each letter at REDCAT (March 27-August 11, 2024).

Installation view of the exhibition Schering Stiftung Award for Artistic Research 2022: Kameelah Janan Rasheed – in the coherence, we weep at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2023; All works: Courtesy the artist and NOME Gallery, Berlin.

Installation view of the exhibition Schering Stiftung Award for Artistic Research 2022: Kameelah Janan Rasheed – in the coherence, we weep at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2023; All works: Courtesy the artist and NOME Gallery, Berlin.

i am not done yet, 2022. Solo at Kunstverein Hannover (Hannover, DE) Archival Inkjet Prints, Vellum, Xerox Paper, Acetate, Plexiglass, Acrylic, Watercolor, India Ink and Oil Stick Painting, Video. Courtesy of the Artist and NOME Gallery, Berlin

Between your personal and professional projects, how many are you working on right now?

I have ADHD and OCD, so the idea of starting and finishing things is not part of my cosmology. It’s hard for me to think about doing a project without doing something in parallel, because all of my works are intricately connected. I'm learning from one project to make sense of another. So there are about six or seven out there.

I can't imagine a world in which your projects aren't in conversation and informing each other, because it's all an extension of you.

Yes. [laughter] I’m laughing because I actually tried to give myself a challenge: to finish one project, release it, then move on. Literally in the middle of doing that, I started another project. And it's not even that I love doing them as much as I really love learning, and if there's an opportunity for me to learn something new, well then, why wouldn't I?

I have a consulting business called Orange Tangent Study. We disperse microgrants to artists for weird ideas that may not be funded otherwise. I was speaking to someone who, unfortunately, didn’t receive a grant, but I offered her a complimentary consulting session. She asked me how I figure out what I’m going to put in front of the world. We were talking about informal practices and that not everything needs a gigantic announcement. You can just be like, "Here's my weird little game I made," or "here's my weird little zine." Part of the reason why I'm working on multiple things at once is that all of them are characters in what I would call a large ongoing screenplay, where they all need each other. And anyone who goes off-stage, they're still in the mix, but they're never exiting the context. In the same way, I think about projects as understudies for other projects. Sometimes I'll get 80% through a project and then realize it’s not what I’m supposed to be doing. I’ll consider it just research for the next thing. It's definitely frustrating for people trying to fund work. They just want a timeline, and I can't give it to them.

That's not how ideation and creativity works. It's not supposed to move in a linear line. Your work is so ranging and searching. It's like you're on a mountain or in the woods and you're just looking for cell phone service. Your work is constantly trying to connect to something else. You can't put a time period on a search.

But capitalism requires a certain sense of finality, and me and capitalism haven't gotten along. I know her. I don't want to know her, but I know her very well. My refusal to follow a linear path is one of the things I've been told has held my career back. I recognize I could be doing more, but I'm happy with what I'm doing right now. It just doesn’t work like that. I’ve tried.

I've heard you talk about going to residencies to play. Work can come out of it, but you're there to have fun. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I think this sounds counterintuitive for a lot of artists, but I never wake up and decide I’m going to make work about blah blah blah and then do it. I’m literally just outside, and something will spark my curiosity. And if it holds me long enough where it shows up in a lucid dream, I talk and think about it a lot, and that's when I know that I have to latch on and do something with it. There’s this thing Muslims say all the time from the Quran: "We plan, Allah is the best of planners." While I take that seriously, I can’t count the number of times I’ve planned things that have not gone my way, so there's always a part of me that thinks I’m putting too much energy into trying to be perfect. I should just put the intention out there and then see what happens.

I think one of the interesting things about this Working Artist Fellowship is that it’s been the first time I was assertively transparent on a residency application and wrote, “Please give me $50,000 so I can study play for a year." I said to myself, "These folks are not going to fund this application." When I learned that I got it, I was actually a bit stunned. Not because I don't think I deserve it, but because I have often found it difficult to actually say what I want, which in this case was to teach classes about play, to make games, and to interact with other people. So I ended up starting something called the Little Octopus School. We have a group opening up soon called Info Dumper Anonymous, which is for people who info dump but don't have an audience for it. And then we're doing our summer reading program, where you get a certificate for reading a certain amount of things. I make objects because they’re visible and tangible, but the thing that I like the most is being in conversation with people. I might be on a plane, sitting with somebody who's interesting, and something about how they smell, or how they look, or what they're saying might impact me in ways I don’t know.

You've referred to some of your texts as ancestrally co-written, which is interesting in light of the atmosphere or attitude you bring to your work. Who are you in conversation with when you're creating?

That comes from Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who in M Archive (2018) talks about M. Jacqui Alexander's Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred as an "ancestrally cowritten text." What seems most important is the insistence that, as she writes of Alexander's work, we "create textual possibilities for inquiry beyond individual scholarly authority." I am excited about forms and methods that dispel the notion that we work we put into the world is made alone. Everything I create comes from decisions made by someone else before me. My parents decided to move to East Palo Alto. And because of that, I had access to certain types of opportunities and experiences. And so there is the intention of sitting with my ancestors and thinking about them and talking to them and doing this work and dreaming—which I take very seriously—but there's also this sense of that implicitly happening regardless of my intent.

The reason why I want to know the name of this woman from the Snowden family so badly is because myself, my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother all look the same. We have all the pictures. Knowing someone’s name is important to me when I’m sitting to make work, whether it’s Constance, Berthina, Gwendolyn, or Kameelah. For me, there’s this notion that if I write or work or make long enough, I will get to know her and what her life was like. I recently learned that most of the women in my family were teachers. I'm a teacher. I don't know. I just feel like there's a sense of being tethered to all of these histories that I didn't know before. I know that when Alexis Pauline Gumbs talks about this as ancestrally co-written, she's talking about an elder who has passed away that she's riding alongside. So that's one register. But there's also traveling alongside someone you don't know, until you reach a point where something starts to make sense.

I think that's the most enjoyable part for me. I can talk, as you can see. Emotionally though, my verbal processing is very slow. I have to write everything out, double-check it, and then make sure everything comes together. Part of my interiority involves trying to accept that, while also becoming confident in my emotional processing. It is okay for me to say things as they come, rather than trying to make sense of them beforehand. Sometimes I just have to say the thing, even if it doesn't come out the way that I expect. There's something that will catch it. There’s a net. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast