We Are What We Consume

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, The Good Life Sign Up Form, Enron Simulator, 2017.

Courtesy of the artistsFor more than a decade now, Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne—who recently concluded a residency at Pioneer Works—have strived to make the biases of abstract data concrete, palpable, and personal, in original and often humorous ways. They explore how automated systems gather and process information, in realms ranging from surveillance and consumerism to labor, ecology, and environmental management. Their popular work, Smell Dating (2016), was a dating service that matched users based on smell alone; it asked them to send in t-shirts worn for three days and nights and then circulated swatches for participants to select a preferred partner from. Four years later, at the beginning of the pandemic, Brain and Lavigne created New York Apartment (2020), commissioned for artport, the Whitney Museum’s gallery for net art. For the project, the duo compiled thousands of New York real estate listings into a fictional property page for one massive apartment. The website’s multiple frames of image galleries show off the property’s 65,764 bedrooms spread throughout all five boroughs.

At a time when algorithmically-driven systems are increasingly affecting societies, and artificial intelligence is changing our lives, Brain and Lavigne’s investigations of how technologies orchestrate our experiences have become ever more relevant and prescient. We recently sat down to discuss their independent practices and artistic process, how their collaboration has evolved, and the what they're working on now.

I've been following your practices for a long time, and also had the pleasure of working with you on two occasions. Tega, your work has consistently explored issues of ecology and automation and the interplay of digital networks and environmental phenomena. And Sam, you've also engaged with issues of automation, as well as the ways that data processing intersects with surveillance, natural language, and more. Together, you have created projects that investigate how technologies shape our agency, and the biases at play in how we gather information.

What I find really impressive about your work is that, on the one hand, it is extremely focused—examining large-scale datasets, the corporatization of data, the aesthetics of the corporate data space—and, on the other, has a lot of breadth. You cover broad territory in your collaborative and individual projects, from ecology to the real estate market, and it always feels like something new and unexpected emerges from the very focused subtext. I think it’s quite an achievement to strike that balance.

Both of you have individual practices, and you collaborate. How do you navigate between the two, and how did your collaboration get started?

It came about in a fairly organic way. We both moved to New York around 2013, and those were really vibrant years in the city’s art and tech scene. It was post-Snowden, and there was a lot of critical engagement with surveillance and data collection, broadly.

We went to this Art Hack Day at Pioneer Works a year or two later, in the middle of a blizzard. We spent three days intensely collaborating on a project where we duplicated the entire archive of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) making just one small edit. We replaced the phrase “climate change” with the word “capitalism.” This kept the grammar of the archive intact, but enhanced its meaning. From then on we stayed in conversation, and started to produce participatory work together, often online, to ask questions of data and its politics.

We still talk about that first IPCC project, called the Intergovernmental Panel on Capitalism (2015). In a weird way it set the stage for stuff that we continue to do. It’s funny, it was also the first time we got into trouble, because we used the “find and replace” command on every single thing that they had ever produced—their website, their reports, all of their video archives—and republished the materials. Somehow they got wind of the website, and then sent a complaint to the U.S. State Department about it. They didn't get in touch with us directly, they just immediately went to a higher power to intervene. We ended up having a funny email exchange with them.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Capitalism is a microcosm of how our interests and skills intersect really well. My background is in environmental engineering. I'm really interested in ecology and how our responses to the environment play out. Sam's background is comparative literature and web development. And, together, you can see in that project that we both like to play with software tools and programming. Although sometimes we focus on other things, in the last decade our work has come back to these questions of technology and the environment.

And narrative also.

For artists working in your area and doing that kind of critical work engaging with politics—or topics intersecting with politics—it's not at all unusual to get into “trouble,” with cease-and-desist letters flying. It's part of the game.

Yes, it's part of the practice, isn't it?

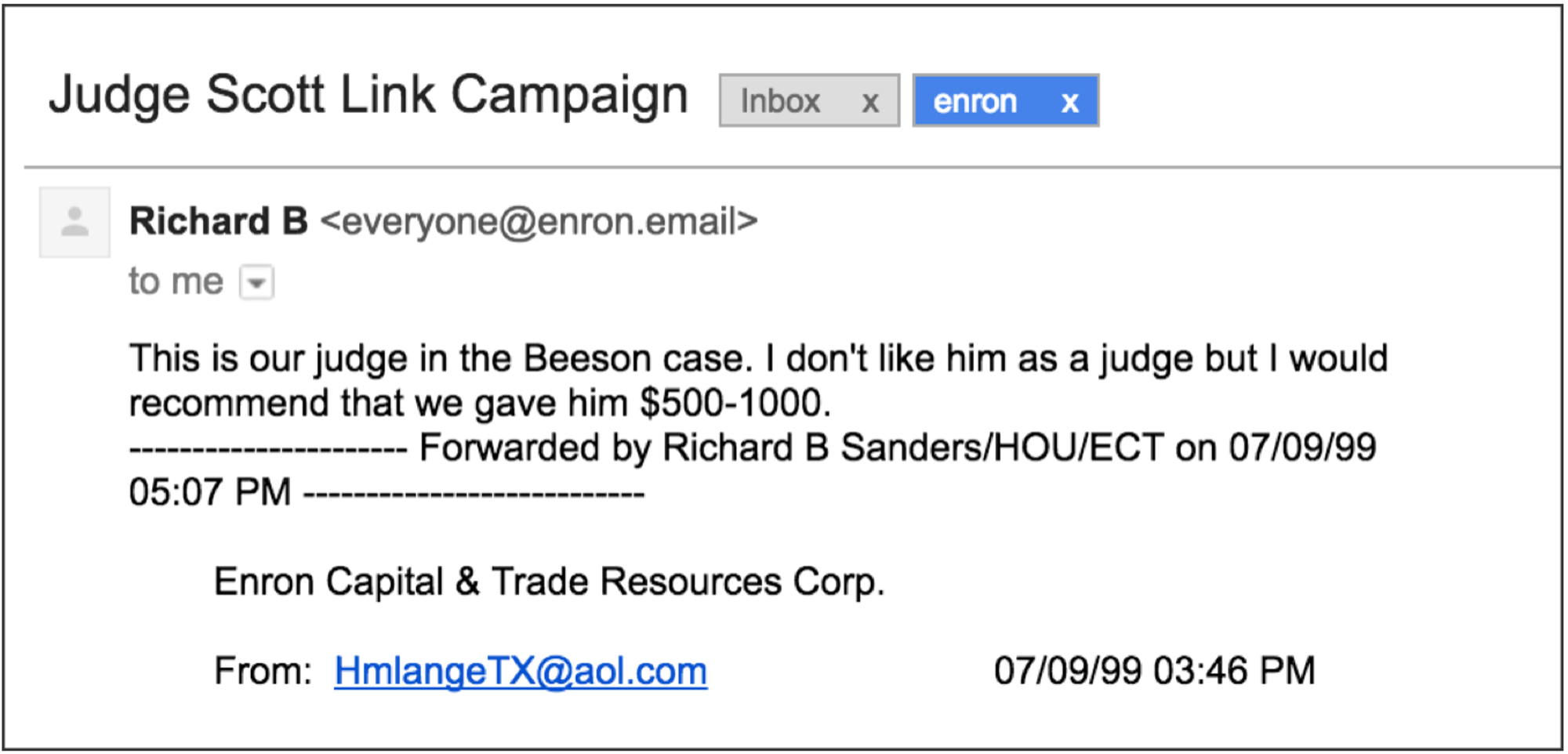

Absolutely. One of your early landmark projects was The Good Life (Enron Simulator) (2017), which explored profound questions concerning the patterns and biases existing in datasets used to train machine learning systems. Of course AI has exploded since then—looking back, has the work’s meaning conceptually shifted? You were clearly ahead of the time.

I don't know if the meaning of the work has shifted so much since 2017, but definitely the question of how we define the English language is more relevant than ever regarding AI. Of course now the people who make language models draw from sources far broader than just Enron’s white collar, corporate criminals. The Enron Email Archive consists of communications from the top 150 executives. It was released to the public after Enron was federally investigated for massive financial fraud in 2001. We used this dataset in The Good Life, which is a service that lets people sign up to receive all of that digital correspondence in their inbox. Initially, you could get sent every message over a five day period, which overloaded our servers. Eventually we changed the timeline to over seven years. It’s an unimaginable number of emails.

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, The Good Life (Enron Simulator), 2017.

225,000.

225,000 very personal, very banal and corporate, and very dodgy emails. You can see the whole rise and fall of that empire. But what we were really interested in was how this archive was used as a foundational tool for machine learning. The first version of Siri was partially trained on it.

I found the immense banality of what these systems get trained on just mind-boggling. You can clearly see the problem of that data becoming representative of, well, anything.

The idea that we could gather enough data to make a universal model for the human language is a persistent, reductionist dream that overlooks how complex and diverse communications and human culture really is. In the years since, the project anticipated how we've seen a lot of researchers and media artists auditing datasets or critically thinking about what's in the data and the decisions made in producing it. Even in 2003, publishing the Enron corpus was a big production. Former Enron employees were hired to filter all the problematic stuff out, like social security numbers. The huge amount of human labor that went into preparing this information makes you wonder who, exactly, is determining what’s “universal.”

Sam and I also really think about this project as a reenactment. Performativity is something we're really interested in. How do you make a time-based performance out of data—something that an everyday person would typically never encounter, or look at?

It's also important to note that your work always has a sense of humor. In Deep Swamp (2018), you nicely tease out the absurdities embedded in machine learning and datasets themselves, which I think is important.

Tega Brain, Deep Swamp, 2018.

Photo: Tega BrainExactly. So, in that project—where a number of wetland environments are managed by AI agents who can modify them—the question of what we optimize environments for was central. Should we optimize our environments for attention? In ways that center a particular species’ perspective? The politics of optimization is so pivotal to automated systems, how they get designed, who designs them, and so on.

In the context of ecologies and the environment, the two of you have recently collaborated on Offset (2023-ongoing), which examines the quantification and financialization of the carbon cycle. And you have also written about it in an article published in e-flux Architecture, “All that is Air Melts into Air.” What are your goals for this work and how do you translate this type of research-based practice into art?

The thinking for this project began when we received a small grant from NYU for a climate-based project, but instead of trying to make something ourselves, we decided we’d redistribute the grant to four people working on the frontlines of environmental activism and who’d been incarcerated for their work. So we spoke to someone from the Earth Liberation Front, someone from the Dakota Access protests, a Sudanese activist, and an activist from Blockade Australia. We split our grant up and gave it to them for their service. Afterwards, we were thinking about how we could make this kind of financial support more sustainable. We started to look at the way capitalist enterprises do this, through carbon credit marketplaces. The way a carbon marketplace works is, for example, I own a forest that’s absorbing all this carbon from the air, and you are Microsoft with all of these emissions from your data centers, and you want to find some way to compensate for those emissions. You can buy the carbon that my trees are sucking out of the air, and then claim you’re doing something that's not negatively impacting the environment. It's very problematic and very bullshitty, for lack of a better word. All it really does is exacerbate the problem of high emissions, while prolonging a status quo that operates on the false assumption that the planet has infinite resources, and that an environmental equilibrium is possible without changing the underlying mechanisms of production.

For Offset, we want to take advantage of this marketplace by calculating the carbon benefits of direct action, like activists shutting down a pipeline for a week, and then selling that benefit as a carbon offset. In effect, we give the earnings back to the activists. It’s a way of financializing industrial sabotage, and takes the data-as-commodity model to its natural conclusion. It also asks what gets to qualify as carbon beneficial to begin with. In a moment where governments around the world are litigating against climate activism, it becomes a weird kind of funding scheme, while also broaching the legality of these prosecutorial efforts. As for your question of how it works as an art project, I think that's something we're still dealing with. Obviously it operates successfully as a concept, but we're imagining these offsets as art objects as well. Tega, do you have anything to add to that?

Like many of our works, Offset exists online, so you can visit our carbon registry at https://offset.labr.io/. We're also taking suggestions for case studies of direct actions that could potentially be listed as offsets. So the project functions as an archive of these efforts and an attempt to actually look at their carbon savings, which obviously has a touch of satire. We’re currently working on launching the marketplace itself, where the actual buying and selling will happen. We've done a number of pilots and experiments over the past year, and in 2025 we’re having an exhibition of our collaborative work at Pioneer Works. Offset will be presented in that show as an installation—a physical experience that will include the certificates, some video material, some visualizations, and a whole lot of research material.

Translating this research-based practice into installations is always a huge challenge. How do you approach that? It's not the first time you're doing it.

I think our strength is storytelling around opaque technological systems, and we use humor and satire to lure audiences into sticky questions. We love working online and using the anonymity and ambiguity of the web strategically. We’re happy if audiences never quite know if it’s an artwork or a real thing. Sam and I are both working on translating this ambiguity into physical experience. We've been looking at different printing techniques for the certificates and thinking about how authenticity or authority is established through printing, like how forging money is prevented through scale and different materials. It's all in process at the moment, but I think trying to connect it with other histories of exchange is what we're trying to do here.

We’re also thinking about the spectacle of finance, and how you can take something that's nothing and attribute value to it. That's one of the strategies we're going to employ in our exhibition. And the other, of course, is taking all the material that we've collected and presenting it in a way that can be explored in some form. So there's this surface-level gimmick of financializing climate activism, which hopefully gives way to deeper engagement with our material.

We've gotten really into how authority is established through the appearance of mathematics and corporate aesthetics, which you can see a little in the Enron project. What do these carbon registries look like? How do you visually convey their authority or establish trust in them? We also try to push this to an extreme where it gets really strange. Sam's been scraping existing carbon registries and LinkedIn for oil company executives’ profile pictures. We've been working with that as a dataset to emphasize how preposterous it is quantifying the world in terms of carbon, and the surrealism of viewing every action for its carbon impact. We want to create really overwhelming experiences.

Web scraping is where you build a computer program to download vast amounts of website material. It harkens back to the very first days of the internet, when the web was designed with no central index so it was immediately necessary for someone or some group of people to create one. That's how search engines came about. They rely on the continual use of web scrapers to build an index of the web. Today, generative AI comes from scraped material—ChatGPT, Claude, all of them. But when an individual does some web scraping, it can be for a variety of purposes. I've been working on this concept called scrapism, which is web scraping as a poetic or cultural practice rather than a business practice.

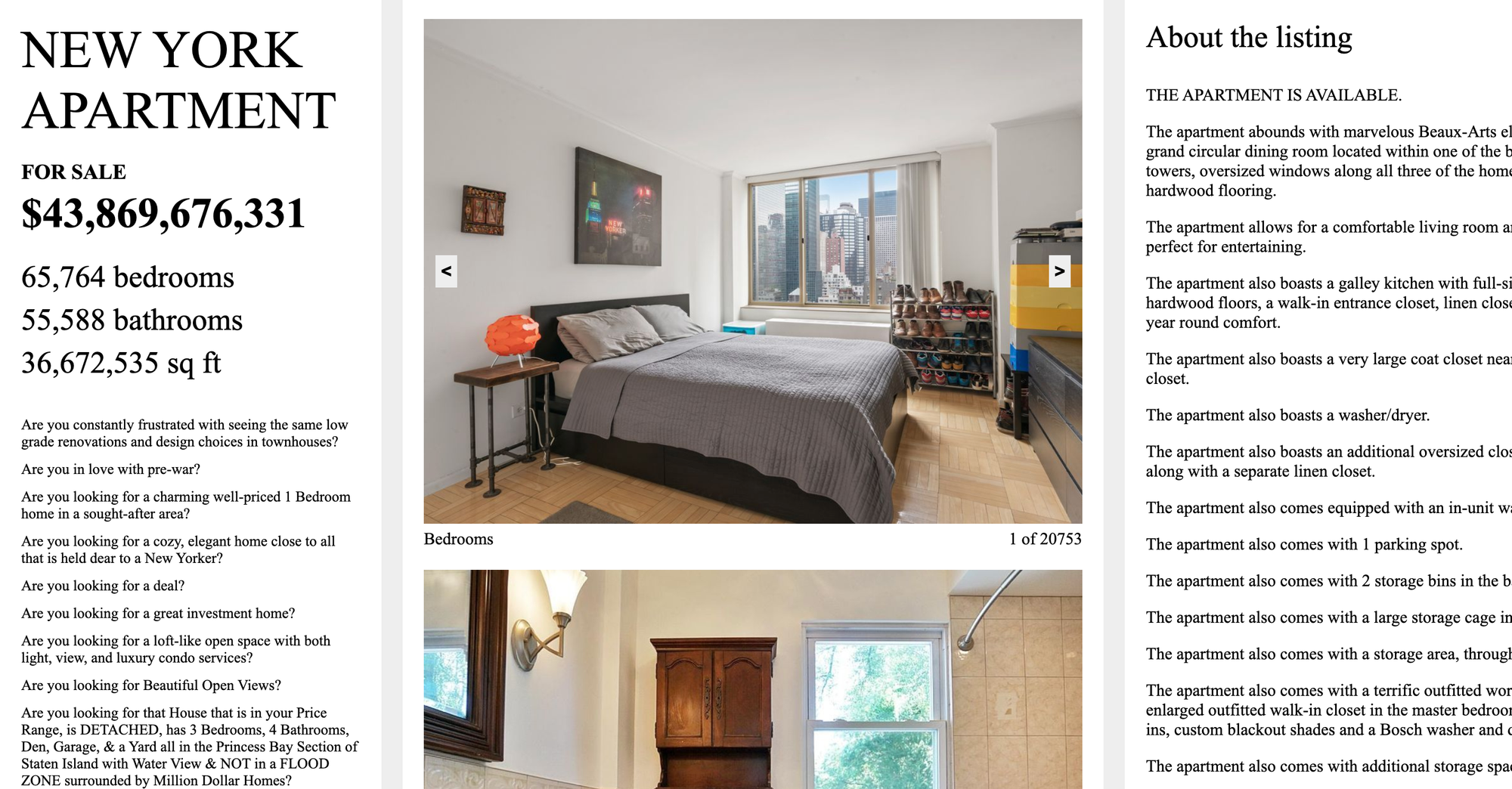

Building on this idea of scrapism, you two worked with me on the Whitney Museum-commissioned New York Apartment (2020) at the start of the pandemic. The piece is a website advertising a fictitious New York City apartment for sale that covers more than 300 million square feet and spans the five boroughs, an overwhelming dataset culled from actual online real estate listings. The work collapses the high and low ends of the market—architectural periods, styles, neighborhoods, and pricing—into a single space. It functions as a beautiful portrait of New York City and its real estate market, and a look at how our aspirations manifest in marketing language. Returning to the poetic qualities you mine from corporate aesthetics, what inspired you to find these moments of storytelling in data?

I was looking for an apartment the year before, and as I'm sure anyone who lives in New York or any big city with housing shortages knows, you spend a lot of time on real estate websites making snap decisions about whether it's worth seeing. Are the images real? How do they correspond to a floor plan? Trying to process a lot of online information all at once is nauseating and stressful. While I was apartment hunting, Sam decided he would scrape the entire real estate website StreetEasy, and create a database of every NYC listing for me. The project obviously emerged from there.

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, New York Apartment, 2020.

Courtesy of the artistsNew York Apartment had a very maximalist approach. We had collected a huge quantity of material—hundreds of thousands of images, descriptions, floor plans, and videos. Typically, when we try to make decisions about what to do with a lot of content, we think about what to cut. But for this project, we were like, let's not cut anything. Let's just have as many things as possible. That scale of abundance is something you can really only do on the web. We were interested in communicating the totality of housing as a commodity, at least as it exists in New York. And so, we just kept adding more and more to it until it became a sublime fever dream.

It also became one of those works reshaped by life’s circumstances. The pandemic hit and suddenly it felt like we were living in this gigantic apartment connected via Zoom, with everybody in their own little spaces that resembled the more abstract floor plans you had created. I think the work really resonated with people in this new context. Of course it was a portrait of the housing market, but it was also a reminder of how we were all a part of this weirdly connected space.

Sam, coming back to what you mentioned in terms of scraping, you’ve created technological tools from python scripts for creating automatic video and audio to a p5.js library. In the ’90s in particular, within the net art and software art community, there was a trend towards tool-creation. The term “artware” was used a lot and frequently. How would you describe that relationship between creating tools and artwork? If you experience it as one fluid landscape, how do tools and art connect for you?

Everything I'm doing involves code at some point or another. And when you're working like that, you often make something quite specific, which becomes interesting for others if you tweak it just a little. If that comes up, it’s very exciting. And it happens in two ways: one is that a project’s code will be open, so that the artwork itself is reproducible. The whole code for New York Apartment is on GitHub. The other way is that I'll be working on something and it’ll become clear that the tool is useful outside of an art context, like my project Videogrep which lets you automate video editing. These tools also become part of my teaching practice sometime. Students will use my tools and modify them, or a new tool will emerge.

Both of you teach or have taught. Tega, how has that informed your work?

We both teach coding and software in New York art and design programs. For me, that's really important, because it's a way of opening up these technologies to communities outside the disciplines that have had a monopoly on programming education, like computer science and engineering. The goals of art and design students playing around with programming are really different from those of, say, people working in STEM. They’re using it critically, they’re experimenting, and of course, self expression is really important. Teaching has given Sam and I a lot of freedom to develop our research-driven work, which is not particularly commercial. Teaching has enabled us to be very experimental and not worry about making money, because we pay rent by other means. Being in the classroom also causes you to slow down and articulate your research and interests publicly. I have some mixed feelings about how much time teaching takes, but find the process of a semester allows you to move slowly through all this material, deal with questions from folks who are unfamiliar with what you’re doing, and listen to countless perspectives to see how these issues land for people from all different backgrounds. The process is incredibly generative. ♦

Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain’s 2023-2024 Pioneer Works residency is supported by the Rockefeller Foundation’s inaugural Working Artists Fellowship program, a part of the Foundation’s The Artist Impact Initiative.

Subscribe to Broadcast