Press Play: No Money in Poetry, The First Year of 1080press

This column is an offshoot of the Press Play fair, the Pioneer Works book and music fair celebrating the merits of independent publishing and the dissemination of the arts through publication, recorded sound, and their expanded mediums.

On a Saturday evening in July, I attend a poetry reading at a test kitchen in one of Bushwick’s converted warehouses, up four long flights of serrated metal stairs, with hand-written signs pointing the way. 1080press has just published the latest of the four chapbooks in its inaugural series. There had been talk of starting at sunset, but it has rained, so the readings begin when it is determined we have a quorum.

Publisher Vladimir Nahitchevansky tells me that, from the beginning, 1080press was "less about design, or even an editorial statement, but about distribution." It’s a month later, and I’ve caught the publisher somewhere between Newburgh and Kingston, NY, on his way home from work. The distribution model is unconventional. Each book is published in an edition of three hundred, of which most copies are sent—free of charge—to an open-subscription mailing list. A small insert asks the reader to consider donating to the poet or to the press, and payment information is given for both.

Nahitchevansky has thus far financed the enterprise through a combination of donations, pandemic unemployment funds, and revenue from the sale of his personal belongings via Craigslist. "The books are distributed for free, and they’ll continue to be distributed for free," he tells me. "And my thinking behind that is—for one, you can automatically reach a larger audience, which is to the benefit of the writers. At the end of the day, everyone more or less agrees there’s no money in poetry." That's not to say poets shouldn't make money, he is quick to add, but since the readership is well aware of the time, labor, and material costs involved, "we've been able to raise money without having to ask all that much for it."

The books themselves are gorgeous—far nicer than anything else you might expect for free. Every detail has been seen to with the utmost care, from the cover art to the typography. The mailing list began with Nahitchevansky’s personal address book and has expanded little by little from there. One of the central factors, he says, that led to the founding of the press was that "none of my friends had books out. So there was nowhere for us to read each other’s work and discuss it."

"I’ve taken stacks of books to the coffeeshop, or the bar," he says, "and just passed them out to people." The press has a website, which apparently crashes any time more than two people are on it. ("It was funny, so I left it that way.") At the reading, on a table in the back of the room, the books are offered for a suggested donation of $5 each.

Nahitchevansky talks about the books “working as sequences,” “workbook-style” in the mode of Philip Whalen, “the poet showing the mind thinking.” (Per Leslie Scalapino, “The poem is always leaping out of one's mind.”) They are full of dreams and dirges. Much enamored of poetry, they are occasionally suspect of its place in the world. They all refer familiarly to friends and lovers, citing them as the sources of myriad inspirations and disappointments. Nahitchevansky enjoys a close editorial relationship with each of the authors, and typically designs their books. “You start thinking of the book as an artist book,” he says, “as an entire piece that’s not being broken."

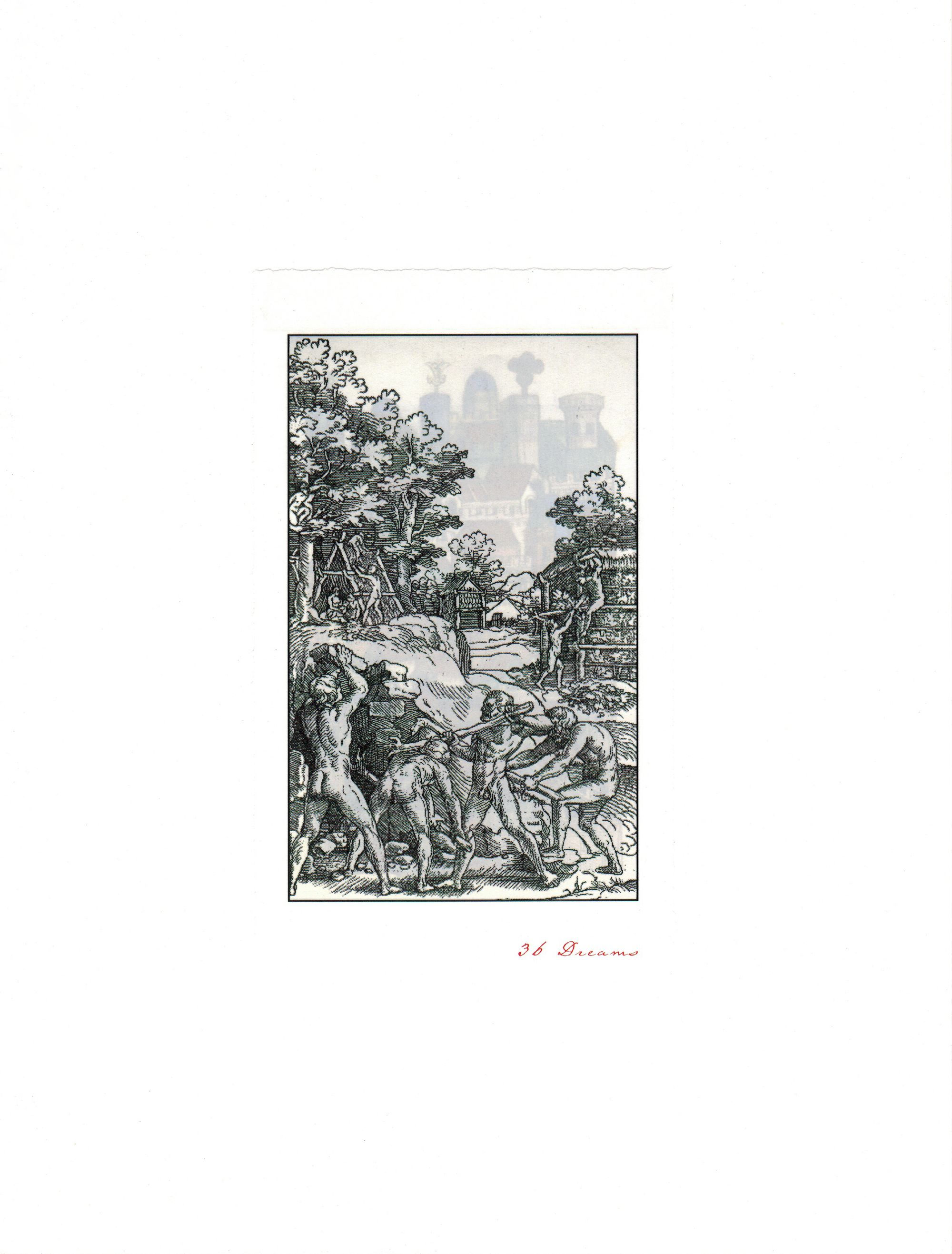

The first book published by 1080press was Terrence Arjoon's 36 Dreams (June 2020). On its cover, a color plate from a 15th century German manuscript sits under a translucent piece of vellum, itself printed with a 16th century woodcut by Georg Pencz. The cumulative effect is of a distant city seen through a haze, with more rudimentary structures being erected in the foreground by naked laborers.

Inside, its numbered blocks of double-spaced prose sketch a world of ritual and expectation, in which the animals of the forest are marshaled for war and espionage. There are references to "the MOUSE CITY," but also to "BRIGHTON BEACH'' and "MARBLEHEAD." The seasons turn rapidly, as in a succession of letters from a distant place. The narrator is variously a young boy and an old man, is either "I" or "you." He seems to live, as many do, in simultaneous opulence and precarity. The book is dedicated, "for Juliet and the forest," and the former appears repeatedly as a character: teasing the narrator, shuffling the coals of a fire, dancing as a vision in a candle's flame. The whole thing reads a bit like the daybook of someone whose relatively placid life coincides with a turbulent period of history.

As Arjoon reads, he wipes sweat from his brow with the palm of his hand and presses it into his hair, which by this manner is held perfectly coiffed above his ears. He is interrupted periodically by the sound of a table saw through the wall; by the churning of the HVAC system; by errant ringtones; and by a mild stutter, which provides for the occasional lyric delay. Finally, he is interrupted by his own deep, boffo laughter, not always with an obvious antecedent, which is met with a scattered response from the crowd, which makes him laugh all the more. Then he reads the next line.

The second chapbook, by Tenaya Nasser-Frederick, is at first illegible. Lavender Cats (August 2020) forgoes the mylar slipcover that the other books ship in, packaged instead with a folded sheet of brown paper. Printed on its face is the first piece from the collection, a concrete poem whose characters only occasionally approach signification and do not linger long. "The plane climbed yellow in teh autumn sky ao r sandy r f os from toot a af clams", one line reads—by far the most coherent on the page. The book continues like this for almost half of its length, with flashes of clarity becoming gradually more frequent.

If it were simply gibberish, there would be no merit to the struggle it makes of reading, but the little that is intelligible is enticing. Even the inscrutable crackles with sentience. “U pu er tongue writ e on a z es lump in we throat” seems a line worth pausing over, yielding different meanings depending on how one resolves its contradictions. Elsewhere, “a grave in heat” is an intriguing piece of solid footing in the morass.

Toward the book's center, the once-dense blocks of prose become more spritely. Finally, the automatic writing machine cycles down, and distinct poems emerge. Some are dated, all from the darkest weeks of New York's Covid-19 outbreak. On April 15, Nasser-Frederick writes, "it seems to me regular speaking isn't true to the irregular interior, isn't even false." The sentiment seems almost a statement of purpose for the entire project, which admits only irregular speaking, valiantly choking on itself along the way. Its stream of consciousness has flooded its banks.

At the reading, Nasser-Frederick begins, muffs the first line, takes a swill of beer, and tries again. Certain moments from the text are rendered as exasperated grunts. When he gets into his stride, the microphone weaves small circles about his mouth in time with the cadence of his voice. After one poem, he looks toward the back of the room: "Someone over there, my phone is plugged into the wall, and I'm gonna need it."

“Sometimes I think of these poems as being somehow darkly comic, but I don’t know if that’s true,” says Christina Chalmers, by way of introduction. She pulls her glasses to the end of her nose and peers over them. In her voice there is the tone and timbre of reading charges or pronouncing judgment—firm, formal, solemn—belying the trenchant wit of her words.

Chalmers finds her métier in navigating the jagged shoals of sense and syntax, picking precisely through her own thorny formulations, rendering their occasional absurdism serious and urgent. Even on the page, the lines demand to be read aloud. Heard live, their polyrhythmic prosody is pronounced in the poet’s sharp Scottish dialect.

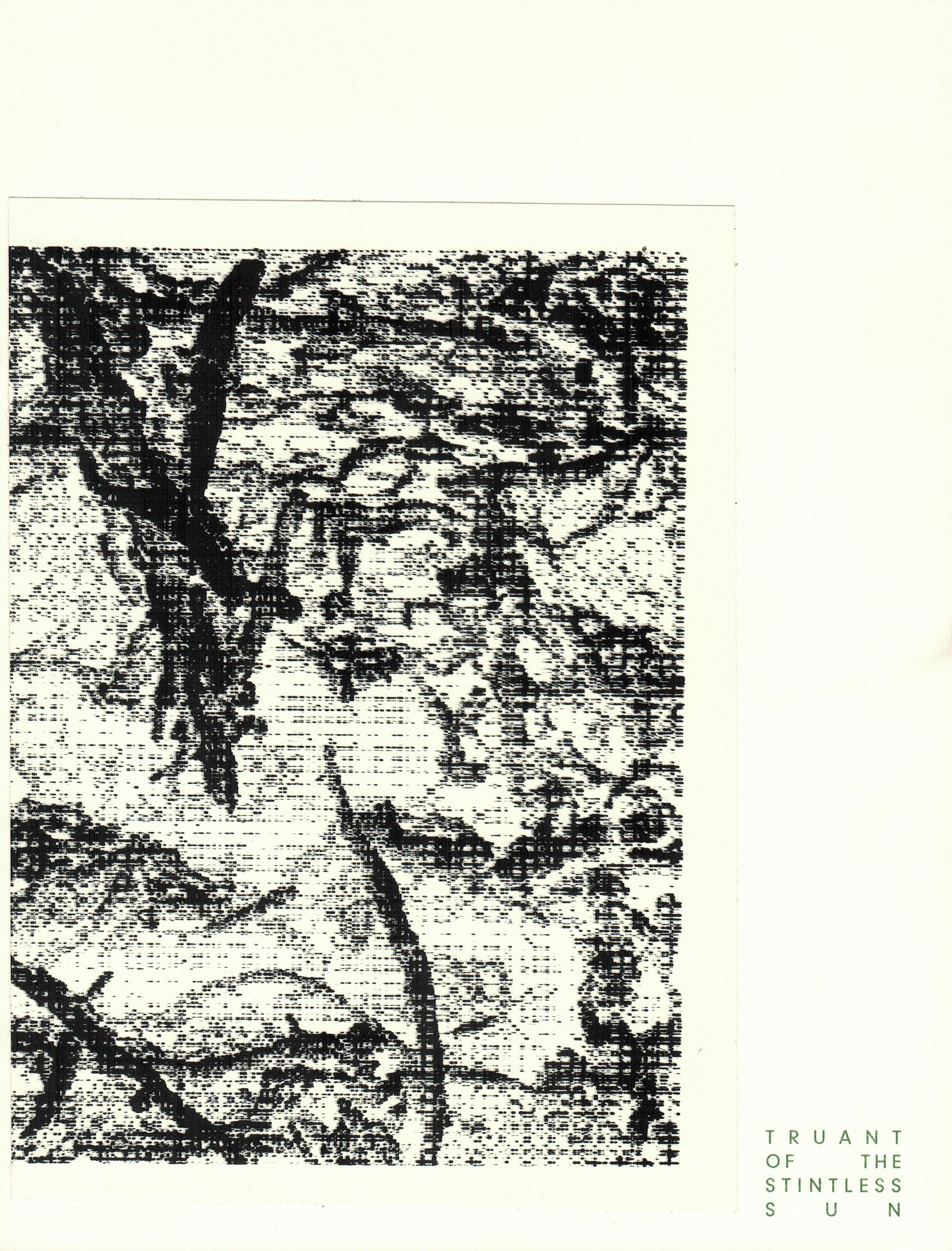

Her book, Truant of the Stintless Sun (April 2021), is adorned with magnified images of dust on either cover, and the poetry within appears resigned to the involvement of our matter with all others', the impossibility of extraction. It laments the endless procession of days, with much to say about the light of the sun, which "comes / and goes daily doing itself / wonders." These might be the observations of an insomniac, someone banished to the other side of the clock. “This is not a representation of hell,” she writes, anticipating the question.

Long columns of narrow lines commingle with blocks of prose. Here, too, is something like a pandemic diary. The poems are mostly dated from the months of February, March, April, and May 2020. Chalmers considers briefly the state of the craft in the midst of a crisis: “The condition of poetry is breath / that is not a condition of life."

From the colophon, we learn the book was written "with the memory of" Chalmers's father, who died in 2019. Much of it is given over to grief. "I love so fucking much," she writes, "the ones / already dead.” She draws the dead “up / and out of the well, like a draught." Elsewhere, she fabulates a "woe that worked." Many of these poems end in moments of brief respite: “I leave me alone.”

When Sarah Lawson brushes the hair off their face, it regathers mostly where it was. "It's just reached its final form," they say of something they are about to read. Lawson rejected an early design of their book, reaching (July 2021), and substituted their own. "They set it the way that they saw it," says Nahitchevansky. The cover was a collaboration: "I had found this box of aerial photographs, and Sarah said, ‘Well, I want them red.'” It was made so, and they were affixed to a matte blue paper. As I bought my copy, I was given a choice of three and picked the one with the most trees. I like how their shadows make the woods look like water.

Like Chalmers, Lawson uses page breaks for formal variation, with blocks of prose seated across from double-spaced verse. The narration's second-person pronoun gradually yields to the first. Densely woven, insistent repetitions knot internal rhyme, alliteration, and consonance for a catalog of extenuating circumstances.

The voice seems to maintain more than one conversation, interrupting itself to speak over its shoulder. Once, a word even invades another: “repla//surrounds//cing.” The poem's comma-separated values are sometimes distinct and sometimes dependent, broken otherwise by em-dashes, semicolons, question marks, lacunae, slashes and double-slashes, and the very occasional full stop.

"You dream you keep the heart and for a little while, I know I lived forever once." Lawson returns to the idea of eternal life set in the indeterminate past. Elsewhere, in a passage of color observations, vision becomes metaphor for feeling: “I feel blue and you feel everything there is to see.” For all its playfulness, it is an intensely personal work. “what do I make public of this,” it asks, and proceeds to answer, by turns tentative and assured.

When I spoke to Nahitchevansky, 1080press had just moved into its own space, near his home in Kingston. The publisher had come into a Heidelberg Windmill, a letterpress printer, so-called because of its automatic paper-feed mechanism. He is also the proud owner of a Vandercook proofing press and a Chandler & Price letterpress. "Whether or not I was aware of it," he says, "I had been acquiring all of the components of a print shop for the past two years and squirreling them away in my apartment."

Although these first four books were printed with G&H Soho, a commercial printer in Lincoln Park, NJ, future 1080press publications will be letter-pressed, xeroxed, and saddle-stitched all in-house. A book by Madeleine Braun, who hosted the reading in July, is currently in production. Nahitchevansky hopes the press can eventually become an autonomous space where poets and printers come together to work collaboratively. He expects to continue providing the results free of charge.

As we say goodbye, he extends a gracious invitation to visit: “If you’re around ... I think we’re gonna print Maddie’s book at the end of October, and the more hands on deck the better.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast