Cartophilia: For the Love of Maps

Cartophilia is a regular column by Pioneer Works alum and current advisor Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, illuminating hidden stories and ways of knowing revealed by some of Jelly-Schapiro’s favorite maps from history and today.

Few emblems of a culture signal more about its values than its maps of how people move. Nothing evokes old Europe’s Age of Exploration like maritime charts crisscrossed with rhumb lines. We Americans, during a century defined by the automobile, came to know our country not through charts of its rivers or rainfall but from highway maps picked up at gas stations. No New Yorker isn’t familiar with an iconic chart of infrastructure—the subway map—by which city-dwellers get around.

During the past year of lockdown and strife, many of us haven’t gotten around as much as we’re used to. But that lack of physical movement has only accelerated our reliance on another breed of infrastructure: the fiber optic strands encased in plastic, mostly, by which we access the digital signals through which we work and play and fill our days, with digital gestures like this Broadcast, conjuring Pioneer Works’ mores and mortar in Brooklyn. The world-wide-web is now essential, as everyone knows, to how culture shifts and grows. But it’s a striking fact of this era that the internet’s literal geography—the means by which our data travels—isn’t better known.

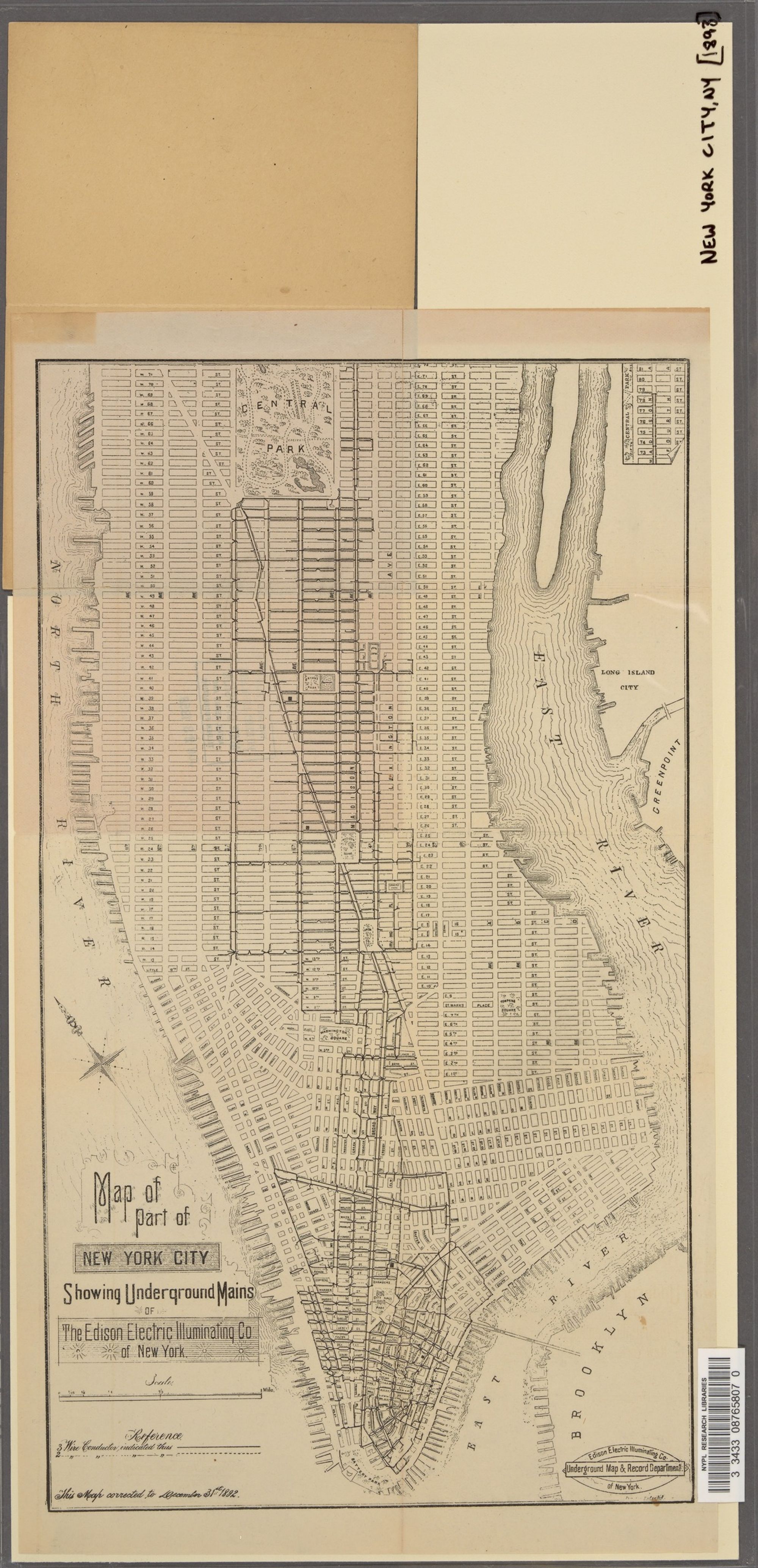

I thought of this fact, and that geography, the first time I glimpsed this gem of a map, from the collections of the NYPL, that charts wires of a different era. Produced by the Edison Electric Illuminating Company in 1893, it recalls an era whose technological magic involved not staring at liquid crystal displays, but causing an orb of glass to exude light at a switch’s flick. It was only a few years after Lewis Latimer, a Black inventor in Queens who perfected the filament that allowed Thomas Edison’s lightbulbs to glow, that Edison’s namesake company rushed to lay the braided copper twine beneath Manhattan’s streets, by which its office-towers’ lamps would spark. But one thing that’s striking about this early map of the electric “mains” laid under New York by the company that become Consolidated Edison, when viewed from the vantage of today, are the way its wires’ lines mirror current-day efforts to map the internet.

When a few years ago the writer Andrew Blum published a book about these efforts, and the geography of the web, he called it Tubes. The title was a riff on an infamous remark by a senescent US senator who described the internet, during a hearing concerning its regulation in 2006, as a “series of tubes.” For that remark, Ted Stevens of Alaska was ridiculed. But as Blum’s book underscored, the senator had a point. Notwithstanding the web’s rhetoric of clouds and wonder and wireless life, the internet is also collection of places like those visited by Blum in his book—a windswept bluff in Nova Scotia, where a key trans-Atlantic cable joining Europe’s data to North America’s hits land; an earthly warehouse in the Oregon desert, where Google’s “cloud” stores your photos on whirring servers; the lattice of old conduit made from iron and clay, beneath Manhattan’s streets, which once were stuffed with telegraph wire but are now lined with the fiber optics that pulse toward internet hubs like the old Western Union Building, at 60 Hudson Street in Lower Manhattan, where lines from across the city and the world converge.

Among the achievements of the Edison Electric Illuminating Company was its opening, on Pearl Street in Manhattan a few blocks from hub at 60 Hudson, of the world’s first “central station”—a breed of power plant that supplied power only to customers directly tied to its wires. That’s not how power works today, in our era of the grid and “network society.” But this map is a reminder that electricity has a geography, too. And that that geography still shapes how, say, this column is reaching you from Brooklyn. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast