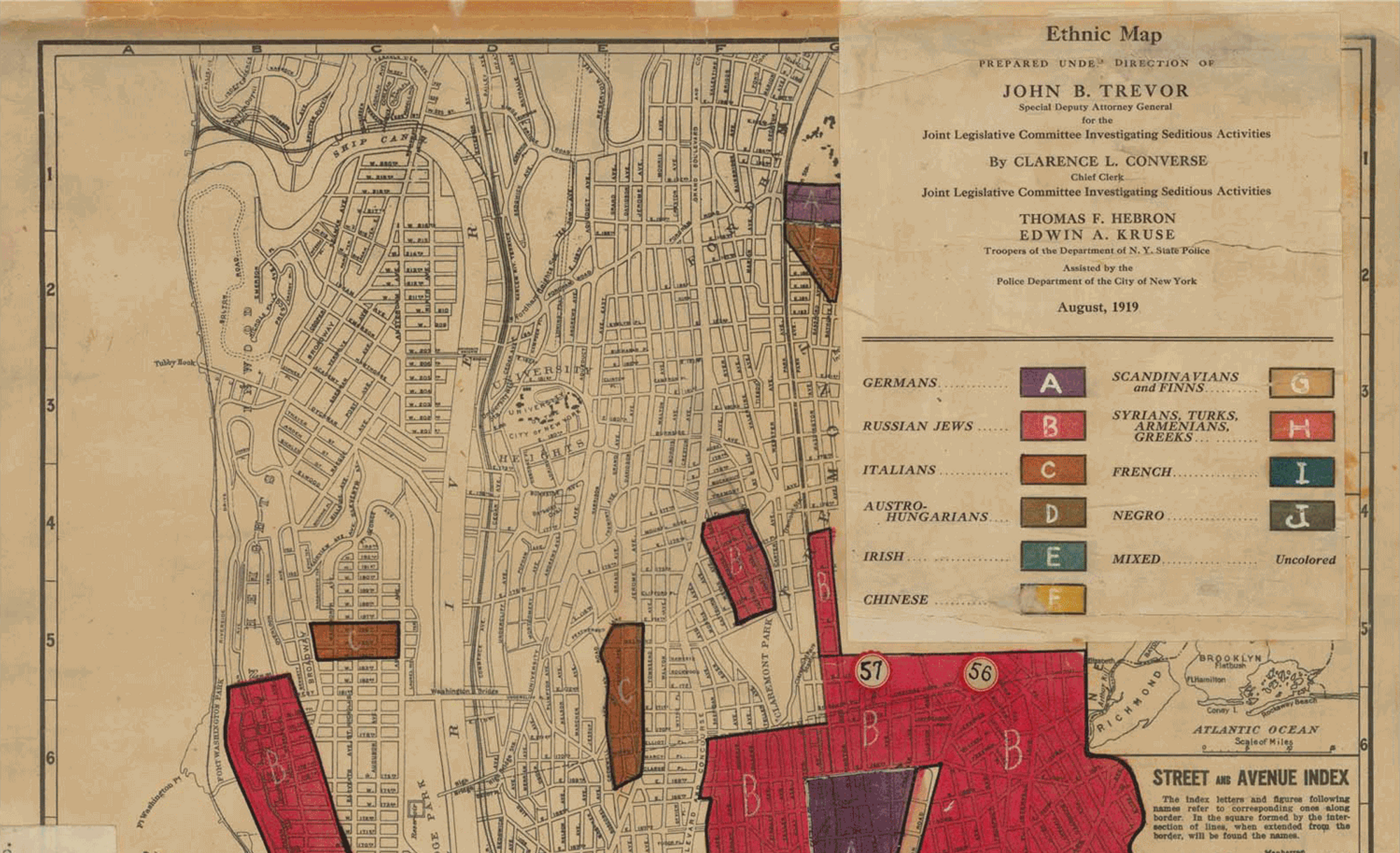

Cartophilia: John B. Trevor's "Ethnic New York"

We’ve been hearing a lot, in our age of derangements and dogmas and violent acts born of mad ideas on the internet, about a vile bit of bred-on-4chan dross called “the Great Replacement.” You’d be forgiven for having the impression, from reading accounts of this “theory,” that all our ills derive from white Americans being “replaced” by non-white ones, that its embracers’ core ideas leapt into existence, from the web’s nether regions, only recently. But as is made plain in John B. Trevor’s seminal “Ethnic Map of New York” (1919), their ideas are anything but new.

Trevor was a wealthy attorney who became America’s most notorious jazz age xenophobe: an unelected power broker, in the Robert Moses mold, who never won public office but nonetheless shaped U.S. immigration policy—and mainstream ideas about who counts as “white”—for decades. Trevor got his start working on Wall Street alongside the prominent eugenicist Madison Grant, whose 1916 book The Passing of the Great Race was a touchstone for their movement. A decorated Army veteran, Trevor became an officer in the Military Intelligence Division after World War I, charged with monitoring Communist sympathizers and foreign agents in New York. Then he moved to Washington to work as a lobbyist. As “special counsel” to the U.S. Senate, he became a key architect of the 1924 Immigration Act––the law that enshrined his and his fellow eugenicists’ obsession with “national origins” as the core of U.S. immigration policy, banning all arrivals from Asia and severely limiting those from Eastern and Southern Europe. That notorious policy, which wasn’t repealed until 1965—when the end of the “quota system” helped create our polyglot populace of today—was Trevor’s central legacy. But it was during a stint as New York’s Special Deputy Attorney General, in 1919, that he drew on his passion for surveilling immigrants to create this map that’s as much a fascinating portrait of the city’s ethnic makeup at the time as it is a twisted portrait, as telling in its gaps and conjured bugbears as in the sites its maps, of the xenophobe’s mind.

By the time Trevor and his cronies in the NYPD endeavored to chart the suspect sectors of Manhattan and the Bronx, such demography-tinged mapping of a city’s zones of ill repute wasn’t new (witness Charles Booth’s “poverty maps” of Victorian London). But one distinctive aspect of Trevor’s visualization of ethnic enclaves was its misleading depiction of them as wholly homogenous, in contrast to those “mixed” zones—left white on the map—that it saw as WASP-dominated. Another is what its color-coded areas suggest about how many people now seen as white didn’t count as such in 1919. Trevor’s map doesn’t just chart the “Negro” precincts of Central Harlem, the Chinese ones of Chinatown, and sprawling swaths of urban space on the Lower East Side and uptown and across the Bronx, colored red for the “Russian Jews” who were, to Trevor, perhaps most vexing of all. (This is a man who later argued fiercely against the U.S. admitting Jews fleeing Hitler.) His chart also maps an olive-tinged thicket of “Austro-Hungarians” ringing Gracie Mansion, “Syrians, Turks, Armenians, Greeks,” circling Madison Square in orange, and too, in a menacing splash of mustard above Mount Morris Park, the “Scandinavians and Finns” then clustered along Lenox Avenue.

The geography of “seditious activities” that’s overlaid onto this map of ethnicity implies a causal link—to be ethnic, here, is to be seditious—that’s made concrete in its 65 sites where “radical meetings are held” and the further 44 where such meetings’ devotees, perhaps, espoused their views in print. Among the latter category are the offices, marked by blue stars, of publications ranging from Voice in the Wilderness to Voice of the People to Negro World and The Nation to a panoply of other lefty rags—from Il Proletario to Klassenklampf—not printed in English. For “seditious” assembly, the spots indicated on this map include a predictable litany of union halls and Labor Temples, and no fewer than seventeen addresses with “socialist” in their names, from the Local Socialist Headquarters to the Greek Socialist Union of America to the Socialist Party, Bohemian Branch. There’s also a place, on Avenue A, called the Progress Casino (not to be confused with the Progress Hall, on East 10th Street), and not a few prestigious institutions of education and culture (Carnegie Hall, Cooper Union). The name of the Beethoven Club, on East 5th Street, may suggest a roomful of music-lovers, but its membership, at least according to Trevor’s map, housed more sinister goals.

It's perhaps a fair bet to claim that Trevor’s own aims, as the kind of man who saw anyone who looked or thought differently than himself as a threat, were more dangerous by far. The need to prove that that’s so, in the century since he surveyed New York, has not lessened. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast