The Quiet Image

Dawn Kim is an artist, photographer, and Fall 2021 Visual Arts Resident at Pioneer Works. For Broadcast, the writer Lynne Tillman responded to a selection of Dawn's images.

Sometimes a wish is evident in a dream, sometimes a picture can seem to picture it. A disaster, broken bodies, and broken-heartedness, a rubble-strewn street. Sometimes smiles and a half-eaten dinner. Susan Sontag wrote “against interpretation”—photographs resist interpretation but also court it. Look at this old kitchen sink, here’s a person whose face is weather-beaten, look at these characters laughing, here’s a battleship in a harbor, sailors on board saluting...

A photographer’s work is paradoxical—making a thing to be looked at, proposing an object for consideration, while offering a work whose meanings are bound to be oblique, an object whose interpretations can vary viewer by viewer.

***

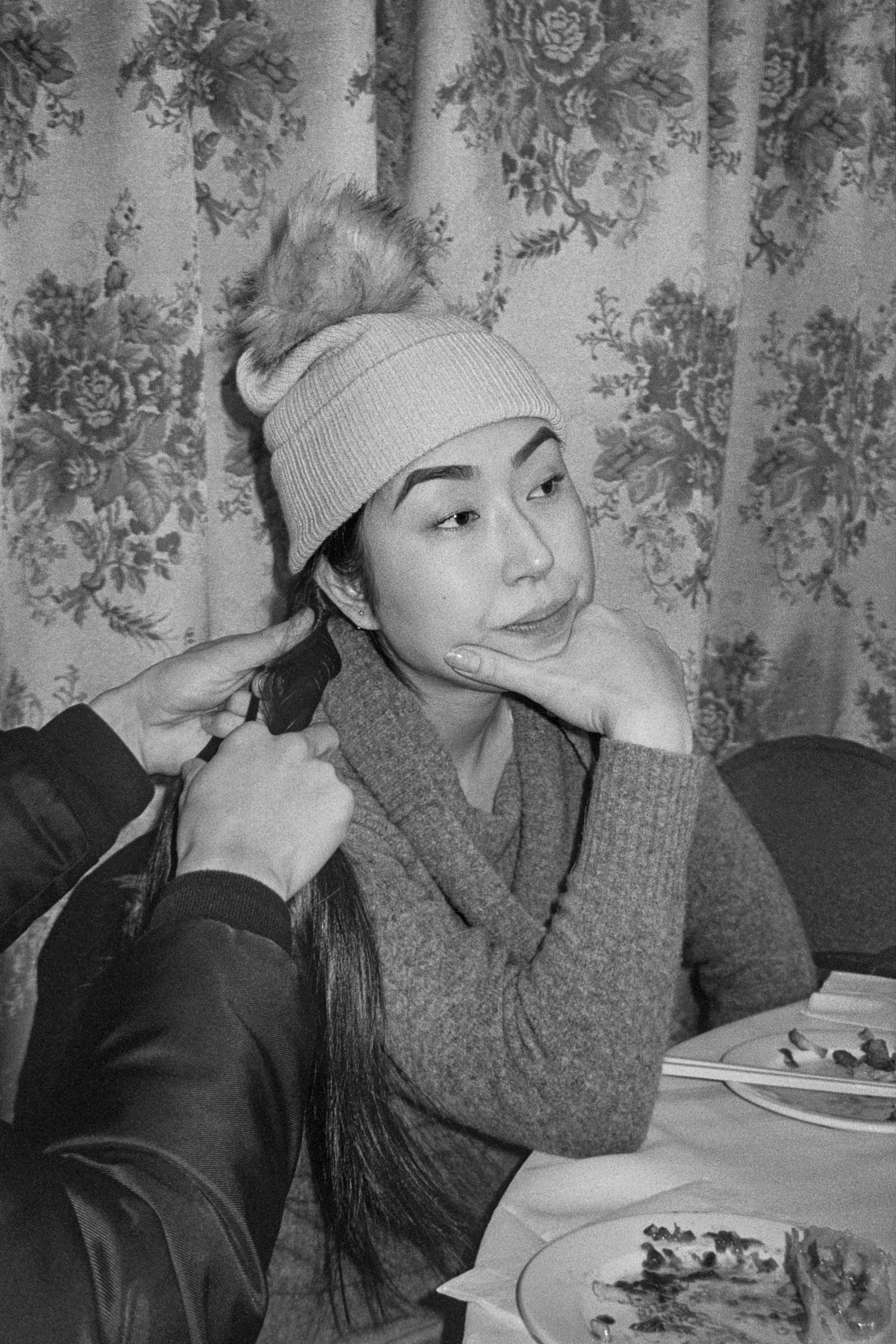

A woman looks away from the camera. Her long, dark hair is held in two hands, probably those of a man. He may be stroking or braiding it. The photograph is in black and white, enunciated by the dark hair and white hat. The woman wears a white, knitted cloche, at its top a fluffy ball. Maybe a faux bit of fur. The cloche covers or disguises much of her forehead, maybe it’s a high one. Her chin rests on her hand, which forms a V-shape, and it covers her chin. The V of her hand exaggerates the upward tilt of her lips, and, like arches, her V-like eyebrows frame her eyes. Floral wallpaper hangs behind her.

She’s in a restaurant, a white plate and chopsticks on the table in front of her. It’s odd that the man, if he is one, plays with her hair there, food around. She doesn’t care, isn’t amused, and might not have liked her food. She didn’t ask him to do it. She seems dissatisfied, faraway in thought, or could be listening to another person at the table. She could be with her family, it’s a Sunday lunch.

The fluff at the top of her cloche is incongruous, because the woman appears serious and determined, and a ball of fluff never is serious. The woman might be about to speak.

In black and white, the work is removed from so-called “real life,” which is in color. Black and white emphasizes its fiction.

I wonder about a photographer’s wonderment.

A wall of concrete divides a landscape. It appears to be in four sections, and juts out diagonally from the left of the frame almost to the frame on the right side. Its placement is curious. In the background, a snow-capped mountain stretches horizontally across the top of the picture. It also doesn’t reach either side, cut from the edges of the picture by two black mounds. The mounds on either side define the space of the wall and the snow-capped mountain. Formally arresting, and not only that, I find myself stopped by it.

In black and white, the scene is denatured.

An abstract work, a geometric space, not a landscape then. Initially, what confronts a viewer is the obvious. The image seems to be interested in the conjunction or perhaps disjunction of culture and nature. But that diminishes the work. Were I to think that, the picture would just represent a sociological idea. The formal aspects of the work are much more compelling.

The word “obvious” shadows, even plagues, the art of photography. Obviously it’s an army barrack, a raging sea. In this picture, Kim is working with a set of forms, obvious objects—wall, mountain, grass—turning it toward something else that’s happening through its composition. A dissonance is constructed through formal means.

In the English and American English language, associations to sheep are not complimentary. A wolf in sheep’s clothing. Don’t be a sheep, a conformist or timid. Sheep are timid, they follow the pack.

All these colloquialisms anthropomorphize the animal.

None of the sheep in this photograph faces the camera. In two rows, six and a quarter sheep (a small part of its rear end is visible, its body primarily out of the frame), Kim presents sheep that are not cute or sweet, they are bodies. They are not individuals, certainly they are not human beings.

In black and white, it’s a somber composition. Sheep are not usually somber subjects—on Google, there are millions of roly poly sheep and sweet baby lambs. Kim’s picture is striking in its profound sense of stillness: they’re lifeless sheep. The photograph’s affect is impersonal, the sheep lack personality, and especially with darkness surrounding them, it’s a melancholy picture.

The three sheep in front are in a line, all sitting in the same way—I thought, like ducks in a row, the setup at a shooting gallery. In the background, two standing sheep appear to be looking at one another, seeing each other. But like statues, they are positioned to face each other, but without a sense that they acknowledge the other, they do not necessarily see each other.

Kim represents living creatures as a still life, as stilled life.

How does the viewer interpret an attitude, if it seems that way to them.

There is nothing obvious about this picture of sheep.

This photograph does not humanize sheep.

It might be a visual commentary on animals and how they are usually depicted. Taking away their supposed human-ness might be why they appear sad to me. So still as to be lifeless, just things, not even animals. Usually a quiet image can produce calm. But this one, this pose, this composition of figures—this one disturbs me.

I am one reader of Dawn Kim’s photographs. Though trying to understand them in formal terms, I am also projecting into them. Over the years, critics believed they could judge work objectively—to my way of thinking, that’s impossible. It’s not even important. Critics have regularly desired absolute appreciation or depreciation of art works, marking good, bad, and I often have wondered: For whose benefit, the artist’s or the critic’s, society’s, culture’s? And long after the artist is dead, the movement, what is it the art proposes to critics who burnish it with praise or rebuke it. It must reside in its meanings to them.

Art doesn’t and can’t stand on its own, and needs responses from others to bring the work into circulation, into discourse. Critics are necessary viewers, because art matters to them. They think about it, study it; they should be knowledgeable. They must also recognize their limits, the way conscientious and conscious artists must. To have a decided position about art, a parti pris, does not address change and differences. New art and attitudes are a sign of different contexts.

An artist, a writer—this one—can be struck or fascinated by how people will understand their art, veering away from their intention, but confirming the theory that meaning is produced by its readers and viewers. Marcel Duchamp puts it so well: “The artist performs only one part of the creative process. The onlooker completes it, and it is the onlooker who has the last word.”

Duchamp is a great authority, because he refuses his authority. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast