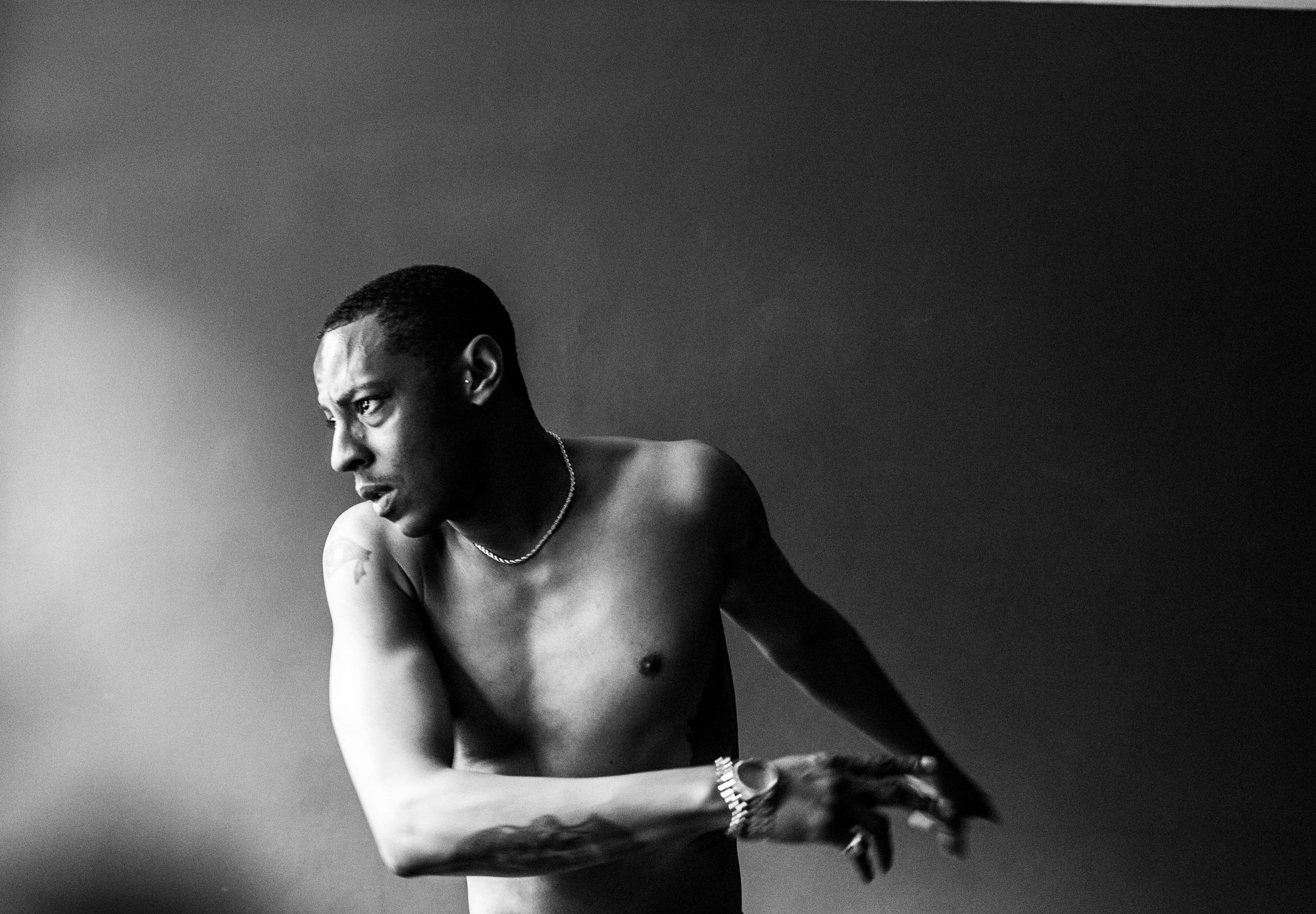

Naeem: Onto The Next Thing

I first met Naeem in 2017, in Wisconsin of all places. He was performing at the Eaux Claires Music and Arts Festival, that Justin Vernon and Aaron Dessner started in 2015. I still remember his performance vividly as I had no real expectations. I knew and regularly played Yoyoyoyo, his debut album as Spank Rock that was released in 2006, but I hadn’t consistently kept up with his music. I just remember Ryan Olson who brought him there telling me repeatedly “Don’t miss Spank Rock” and it ended up being one of the best performances I had seen in ages. Over the last three years, I’ve been lucky to witness the growth of Naeem’s artistry and he has been an essential part of Pioneer Works programming. Performing with us on numerous occasions and last year he participated in our residency program as he was departing from his Spank Rock project and releasing new music under his mononym.

How old were you when you started performing, standing in front of a crowd with a mic?

I was probably like sixteen, when I was first rapping in front of people. I was really bad at it.

Somehow, I don't believe that. Because every time I have seen you perform, you are so hard on yourself and you're like "I was terrible” and you killed it every single time.

[Laughs]

You might've been sixteen and just had the gift off the bat.

Yeah, I don't know. I had dreadlocks and I was a backpack rapper and I was learning how to rap through the Raucous Records scene. Mos Def and Kweli were my favorite. Also Boot Camp Clik, Wu-Tang–trying to learn how to rap from there. KRS-One was really influential for me for a minute. Common and The Roots. Black Thought was super influential. I was trying on all these very wordy, technical, jazz-rhythmic backpacker raps.

It wasn't until I started working with Alex Epton and we did the Spank Rock record where all that changed. I remember Alex was like, "Yo, Naeem, you're way more fun than this. All you want to do is party, so why're you talking about all this serious stuff?"

I love the fact that Alex was like, “maybe you're not being your full self.” I think with Spank Rock I got off-balance a little bit; it was too much party, and I think this album feels more well-rounded for me. Like who I am actually as a person. I’m able to have more control and bring some of that more serious side back into the fold.

I was reading the interview you did with Moses Sumney where he asks you, "don't you want to be more than a rapper? Don't you think of yourself as more than a rapper?"

And you said, “I'm a rapper, I'm proud of that.” Basically, “rapping is a thing of artistry.” Which was really beautiful. It's that endless conversation about the merits of craft and art. In your view, which is mine also, craft shouldn’t have to be placed under art.

But with this album I can't describe you as solely a rapper anymore. Like if I played someone Startisha, a few of the songs would work just fine, would even fit seamlessly into the Spank Rock catalogue such as ‘Woo Woo Woo” then if you played them “You and I” for example it would just confuse them. They’d be like, “wait—this ain’t rap!”

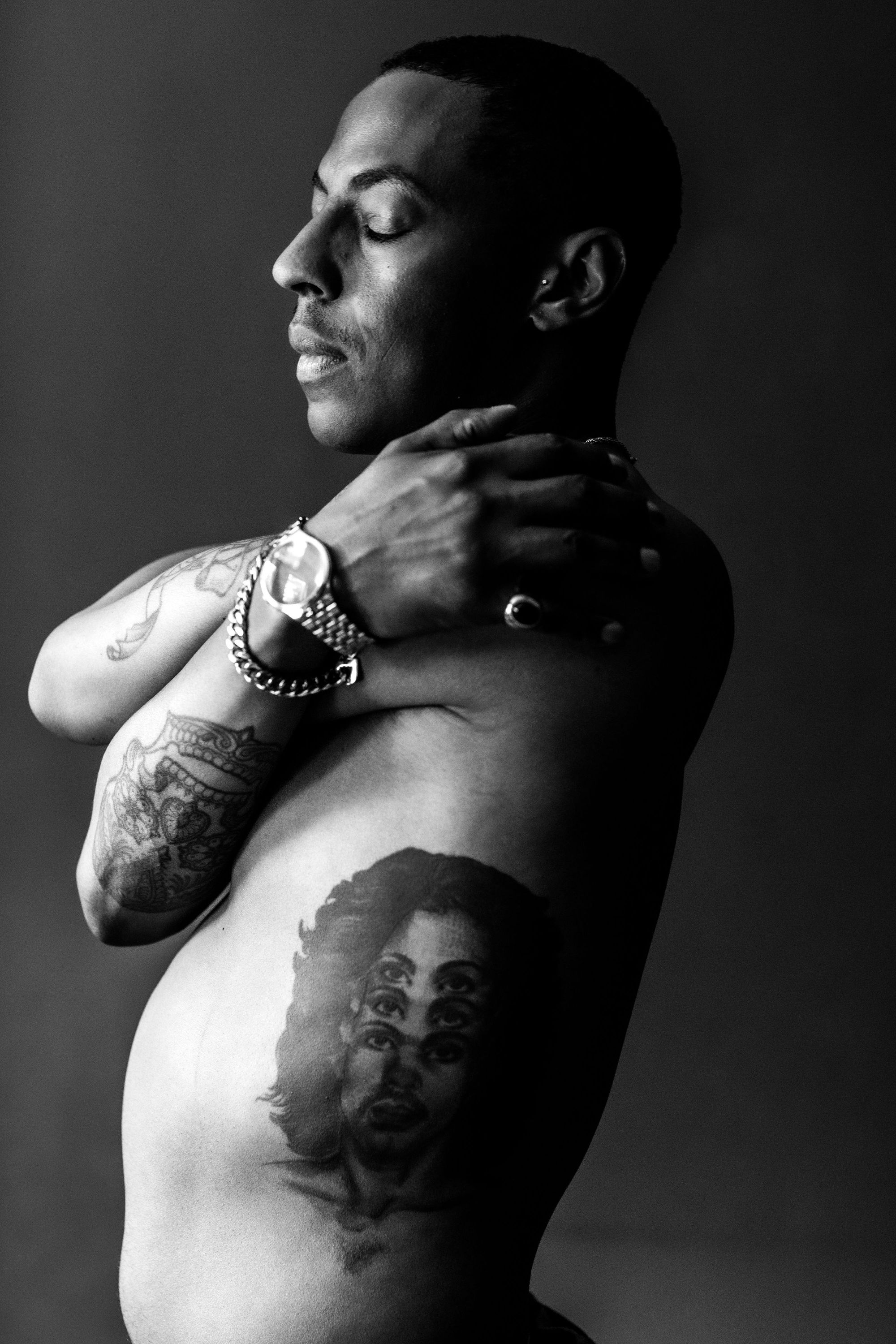

I always wanted to be a musician. I wanted to be Prince my entire life, but I never learned how to play an instrument. I didn't know how to sing. I still kind of don't really know how to sing. Rap was a way for me to get as close to be a musician as possible. I love rap music. I grew up on rap music. But the music I listen to at home is not usually rap. Probably like by the age of like twenty or twenty-one, I was only listening to singer-songwriters. I'm always listening to Prince, always listening to Bowie.

And in your house growing up, what was your family listening to?

Everything. My mom and dad are really big music fans. My mom leans a little more into rock. Elton John and David Bowie are her favorite artists. The Beatles. Very big Beatles fan. But she also listened to a lot of P-Funk, massive P-Funk fan. And on the other side of that, my dad listened to a little bit of reggae, definitely some hip hop. I remember Boogie Down Productions, and KRS-One. And then, like, Tracy Chapman. I remember going to see Tracy Chapman with my dad when I was probably seven years old.

I still remember that iconic album cover.

Exactly. Any records that they brought into the house I would play the records and read all the lyrics. A lot of my joy for music is lyrically based. I know so many Prince songs by heart. I could probably sing that Tracy Chapman album even today because I was reading the lyrics as it was playing. And I think that's what kind of got me into liking rap too because I was actually listening—the words meant a lot to me. The poetry meant a lot to me.

Startisha feels like it has different places in it and a real evolution. What, over five years, were the cities and places and people that were crucial to Startisha being a fully formed thing?

It's definitely a Philadelphia album through and through. Sam Green and Grave Goods get executive production credit on the album, they’re two kids from the Drexel Music School in Philly. I wanted them to be in Philly because I wanted to be able to walk to their houses. I only wanted to work with producers in the city I lived in, because I needed to make music as a daily habit. My writing process there was happening while I was walking to these studios, even catching the blue line out to West Philly - the train kind of goes from underground to above ground and once you hit 52nd Street you start seeing all those ESPO graffiti messages on buildings, and they would end up influencing my songwriting.

Then once most of the songs were written we took it to Minneapolis to work on it with Ryan Olson. Then that turned to something I didn't even expect to happen. I didn't expect Justin Vernon to be involved. I didn't expect Velvet Negroni—I was always a big fan of Jeremy and that first Velvet Negroni album. Everyone in Minneapolis would just hang out together all the time, you know, always collaborating and shit. And I don't like collaborating. I keep it really small.

But once I got into that world it opened up to being something I couldn't imagine on my own. So, then it became like a Minneapolis album.

Right. So, its language is all Philly but then it has a Minneapolis accent over the whole thing.

Yeah. And the reason why it took a long time was because I was building relationships. I was also changing the way I view being a songwriter. Remembering that songwriting is not—or at least the way I want to practice it—it’s not for selling a product; it's for capturing the spirit on record that's supposed to last for all time.

I really did take my time because I wanted to be able to look at the credits of this album and be like “fuck, I love every single one of these motherfuckers. Every single person that touched this album is a true friend of mine.” I wanted to feel that way at the end.

And that takes time because you have to build up trust. Me, Sam Green, and Grave Goods spent a lot of time becoming brothers through this. I remember we were in Minneapolis working on the record and shit was not going well and we had to like to go back to my apartment and sit there and talk to each other really openly and honestly and it got heated and it got emotional. Then from there we got to the other side of our relationship where we had full trust in one another.

But the practice was always about capturing the spirit on record. So, it's all the honesty, forming strong relationships, and this group of people working together to capture what we were feeling in that moment in time. Which makes the music valuable regardless of what I feel about it.

I know you don’t give outside critic to much thought. But it is something that anyone putting something out hopes will come through positively, or at least not get totally overlooked or slammed. There is that nervous wait and right when Startisha had just come out, I still hadn’t seen too much about it and went into a coffee shop in Red Hook and the New York Times was just open on the bench and your picture was on the front of the arts section. I just screamed I was so happy. I had to apologize to the gentleman standing six feet behind me. It wasn’t just because I know you and it was surreal, but It just feels so good when recognition is put where it should be. How does that feel for you that this album has been received so well?

When this stuff started coming out in the press, I didn't have any expectations for it. I already knew people didn't necessarily like me as an artist and weren't really waiting for my next album to come out. [Laughs] No one gave a fuck because Spank Rock or Naeem could never put out another album again and no one's crying about it.

So, I had very low expectations about how it would be received. Once I started seeing it being talked about and it being received well - it doesn't make me view the music any more positively. Like I don’t feel it as validation but I do remember all the hard work I put into it, all the hard work we all put into it, and the intention of it was never to make like a hot commodity for the moment that, is going to have like 100 million streams.

I guess when people respond to it in a positive way, I know that they're actually responding to us being successful in capturing the spirit on record. I like watching people. I like knowing that I was successful in capturing spirit.

As far as the gap between an album getting great press and that actually transferring over to making money. It seems to be such a struggle to actually figure out how to navigate. How do you feel about where the industry is at now, as you have seen it change drastically over the years?

The industry is actually better off now than it was when I started. When YoYoYo came out, that was at the beginning of things completely falling apart. Now they’ve found out ways to monetize music through the Internet and you have more chances of making money.

You just have to be really aware of like how the numbers break down. A million Spotify streams equals something like $6,000.

Damn, I thought the goal was to get to a million...

[Laughs] Right, right, yeah, exactly. It's just weird, because a million streams...

That's a lot!

That's a lot. That's real engagement.

And $6,000 is unfortunately not a lot. Well in America, at least—that’s for sure.

Right, right, right. That incongruity. You can feel successful by looking at one number on the Internet but in real life the number becomes way, way smaller. You just have to know how the numbers break down because then you can set your goals.

I like that musicians can put out music on their own now. If I was to put this record out independently and I made six thousand bucks and that money came straight to me, then I'd be like, “okay, I'm chilling.” But now it’s being split between record labels and things like that. You just have to really learn about how the numbers break down and how to move forward.

I'm not someone who's driven by money, by making money. Money has never motivated me. Popularity also doesn't motivate me. [Laughs] To not be motivated by those two things, I'm just fucked, you know?

Recently, I read a review of Startisha where the critic describes you as “this kind of like closeted gay kid.” I realized we never discussed that moment in your life. So, I wasn’t sure if that was the case. Was that the experience of coming into your own sexuality?

No. I got kind of upset when I read that, basically, he said like, “the song 'Startisha' is about Naeem reminiscing to an old friend about growing up as a closeted gay kid in Baltimore.” I didn't grow up closeted.

Right, it’s like he’s building your character for you and not letting you have your own identity.

Exactly. One thing that makes me really comfortable in being an artist is knowing who I am and knowing that my life is not just a cliché. I like that.

What was your experience like?

Well, I didn't know what gay culture was. My parents didn't have any gay friends. I went to a private all-boys school—being gay there was not an option. I had no understanding or awareness of what it meant to be gay or what gay was other than it being a negative thing.

Since I didn't understand my sexuality as being queer or gay as I was going through my adolescence, I didn't and don't know what it's like to be like a closeted gay kid in high school or middle school. I wouldn’t and can’t place my experience in a binary.

I don't know what it's like being twelve years old and starting to develop a sexuality and realizing you're gay and your sexuality doesn’t fit with anything else around you. When I was going through puberty, and I was becoming more sexual, I did what others were doing in that I gravitated towards women. That's just how it was. That didn't change until I went to college and I started meeting people who were open and out and actually gay. That’s when I understood, “oh, gay people actually exist?” [Laughs]

To me as a kid, it was just a myth. I'd never met a gay person before in my life—I mean an openly gay person—until I moved to Philadelphia. When I had real representation of the LGBTQ community in my life is when I realized it was an option, one I wanted to explore

It’s interesting that this writer felt comfortable to reduce your experience that is more generic and fits the general bill of what most ignorant people assume it is like to be gay.

Right. Growing up in the ’90s we didn't have the same vocabulary to talk about sexuality like we do today. It's way more common now to talk about sexuality as being this spectrum. We say we're “non-binary” or we're “fluid”—we didn't have that vocabulary or perception. I didn't even know to think about sexuality that way.

It’s funny my experience was a bit different from yours. My dad's gay and I was raised around so many gay men and gender fluidity was a sort of norm I was brought up around. I was always like, “why don't I like boys?” [Laughter] I’d wonder, “why am I not gay? Why am I straight?”

Each of us have distinct experiences of coming into sexuality. I think it’s important for people to hear stories of personal truth—so that for people who are going through their own experience know there is no real “Norm.”

I think I told you, but the first James Baldwin book I read was Giovanni's Room. It’s a story about a white American guy who is living in France with his girlfriend. When his girlfriend goes on vacation to Spain, he has this gay experience. James Baldwin describes that feeling like a beast is awakening inside this person. And I was like “oh, that's like . . .okay”. It made sense to me. That's more how I dealt with my sexuality. It was like I didn't even know that was there. I didn't even know it was an option—then it appeared and exposed itself.

And I read Baldwin's book after I’d already had a bunch of boyfriends. I wasn't even wrestling with it.

So, it was the first time that the idea of a gay experience resonated with you?

Right. It's always been really important for me. It makes me feel like I have something to say. And also, I think it's unfair to my boyfriend. He knew he was gay at a very young age and had to go through coming out to his family when he was living in his parents' house. That fear to me is unimaginable. I didn't have to go through that, and I couldn't imagine having to go through that at a young age. I think a reductive critique of the experience takes away from those people who did go through that. When kids go through that at a young age they run away from home and they become homeless. They get shunned, a lot of kids, they kill themselves.

Some people’s stories and so many people’s current realities are unimaginably difficult and intense. How long have you been in a relationship with your partner, Scott? Eight years?

Eleven. I wrote a song for him on the new album. It’s called Stone Harbor.

Man... That’s the song that you listen to and you're like, “I wish that somebody would write a song like that about me.”

I set some rules for the album and one of the rules was to write as many love songs as possible. [Laughs] I felt like I woke up one day and I had been in a ten-year relationship and at the end of it I still viewed myself as this like very independent, crazy “drugs, sex, and rock ‘n’ roll” sort of like kid. And I was like, “That's not your life. You've been in a relationship for ten years now—you can write a love song.”

And so, writing that song was just about coming to terms with the fact that I'm not that cool rock ‘n’ roll guy that I [laughs] imagined myself to be anymore.

How can I go through life without trying to write a love song? I was embarrassed that I had never written love songs before. What does that say about me?

I don't think Spank Rock could write a love song. You had to shed the Spank Rock moniker because it was limiting. Do you feel like you’ve had to reinvent yourself with your new name? Are you relieved?

There's definitely a relief. I hate to quote a music journalist . . . [laughs] but Rolling Stone just put out a review and the writer said, "Naeem's new album is not as much a reinvention as it is an epiphany."

I was like, “Holy fuck.” I was like, “That is what happened. That is what it was.”

That must've felt good to read that. I think sometimes you are too self-deprecating and don't give yourself credit for doing the things you do.

I never thought of it before on my own. It's true, it was an epiphany. At the beginning of making this album it felt very depressing. I was setting rules for myself to get through the process. But I think setting those rules was an epiphany. It was like, “who do you want to be? You think you're this amazing musician. You want to be Prince or Bowie or whatever, but you've got this puny-ass catalog. You have not written a love song before in your life.”

This is where the epiphany came from, the feeling that, if I want to actually be like the artists, I admire then I'd better fucking wake up. Completely change the habits of how to commit myself to be a songwriter. That's the epiphany, being like, “all these things that are clouding my mind or distracting me or making it hard for me to produce, I can get rid of them. They have no space. I can take my time. I can build new relationships. I don't have to be cluttered with negativity or doubt.”

It was an epiphany I didn't even recognize as an epiphany. It felt like I was acting out of desperation.

Spank Rock meant a lot to a lot of people, including me. That must've been intense, to change your name. What was that feeling like? I remember, even I was scared because although I knew the name change was necessary artistically, it was a scary prospect commercially.

It wasn't scary to me. I didn't want to change my name for a very long time because I felt like it was recognizing I failed. The fact that I couldn't keep Spank Rock going, to me that was a failure. But then, this time around, changing the name felt like a fresh start, like I was shedding something more than changing something. I was getting back to a truer, more elemental experience. It wasn't scary; it felt refreshing.

Epiphanies are exciting because when they arrive––it feels like they’re coming from God or something. There's a little bit of magic in an epiphany. I was ready to give myself over to it.

Subscribe to Broadcast