Debut: Lauren Lee McCarthy's "Muted"

I think one day we will be able to go outside again. Honestly, I am fantasizing about this day. Seeing you. Reaching out and touching. Breathing, talking, anything really.

These lines are from the beginning of Lauren Lee McCarthy’s work Later Date (2020), an early-pandemic performance in which the artist hosted text-based, one-on-one chats with people to imagine future plans that could only transpire “later.” Once meeting up was possible again, McCarthy planned to share the chat transcripts with participants and make a date to enact their plans. This would be the second part of the work, or a way to bring it to completion. Over a year after the piece was created, as both the pandemic and the question of how to safely share physical space with one another lingers, the idea of “later”—as well as the work—remains unresolved. But in a moment when it feels like there are no clear timelines, irresolution seems fitting.

As 2020 blurred into 2021, McCarthy continued to process her reaction to the evolving pandemic through four more performances, which would later comprise her Muted series. In its own way, each piece explores questions of mediation, vulnerability, and intimacy through the lens of COVID-19, digital technologies, and the newly outsized effect of both on our lives. In one performance called I Heard TALKING IS DANGEROUS (2020), McCarthy would show up to friends’ doorsteps to deliver a monologue via text displayed on her phone screen. Participants were then invited to visit a URL to continue a text-based, in-person conversation about danger, safety, and the uncertain future.

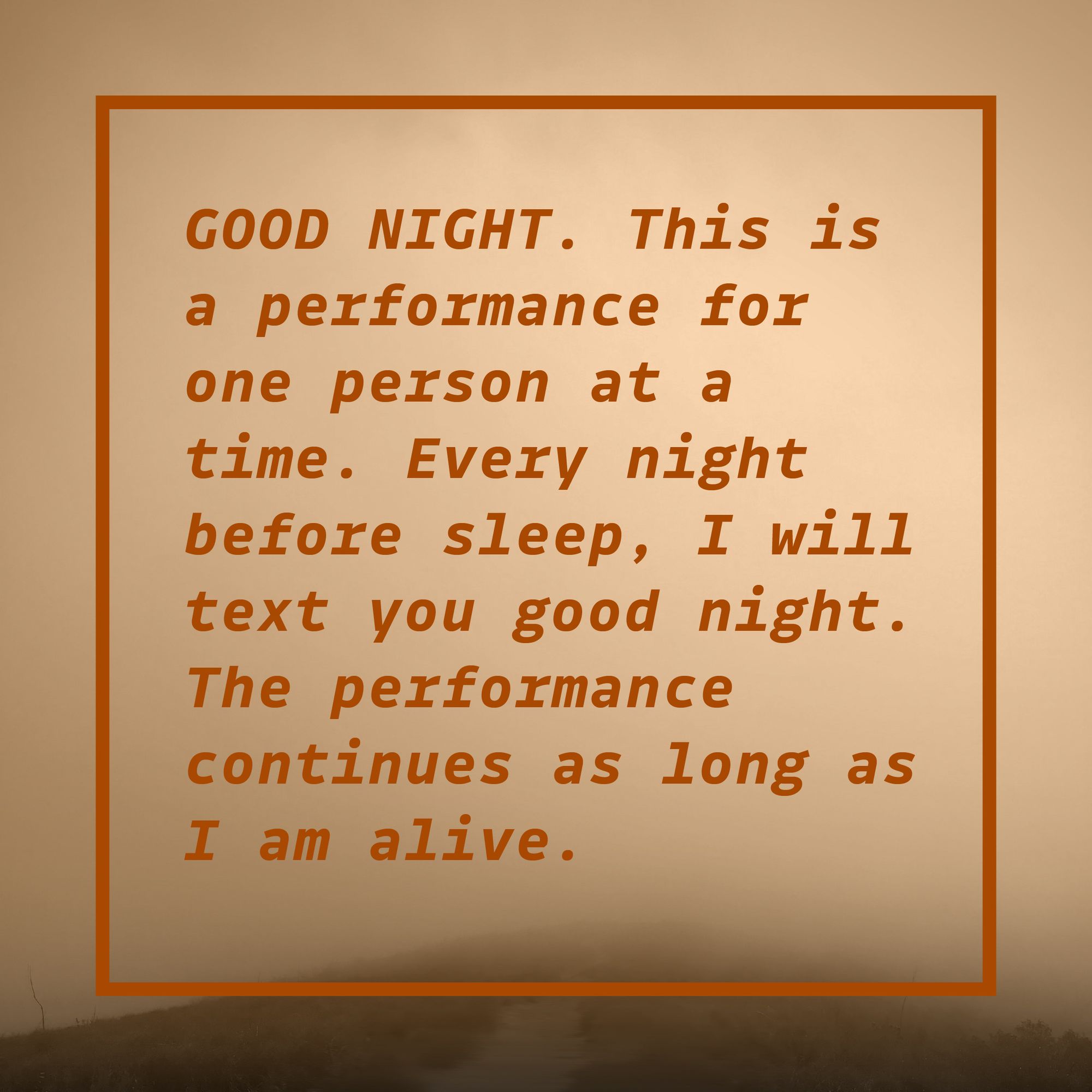

In another performance titled What do you want me to say? (2020-21), McCarthy created a digital clone of her own voice that anyone could control through their browser as a way to say “all the things [they] previously hadn’t been able to embody.” Two more performances, titled Sleepover (2020) and Goodnight (2021-ongoing), each position McCarthy in relationship with another person in ways that feel both intimate and estranged. In the former, McCarthy would show up to a friend’s yard with a sleeping bag, text them “hello,” and then spend the night outside their home—without ever coming into physical contact. And with the latter, she promises to text “goodnight” to a designated recipient every day before she goes to sleep for as long as she is alive.

Throughout the series, McCarthy uses tech-mediated performance as a way to experiment with questions of presence, intimacy, and safety, and to conjure possible alternatives for maintaining connection across physical divides. Now, the artist has stitched together documentation and poetic impressions from the five performances and synthesized them in one web-based work. Titled Muted, the multi-sensory piece uses text, audio of the artist’s voice, sound recordings, and photo documentation from each performance to take viewers into McCarthy’s emotional state during the pandemic as she struggled to make sense of it, process its intensity, and move forward. Please click Join to experience the piece, and read below for an interview with the artist about creating Muted, experimenting with accessible web formats, the pandemic-induced digital age, and what it feels like to confront one’s own mortality.

– Willa Köerner

To experience this work through a web browser, please click here.

I'd love to rewind back to the beginning of the pandemic, and your first performance of what would become the Muted series, Later Date, in which you hosted one-on-one chats with friends to fantasize about future plans. Can you bring me back to that moment?

At the beginning of the pandemic, I felt very anxious. Since I couldn't see or talk to anyone, the performance came out of my need to feel a connection with other people, to ground myself in the intensity of what was going on, and to process it.

I'm sure you remember in the beginning when everyone thought, "We're going to shut down for a week or two." As that timeline evolved, events kept getting postponed until “later,” but we didn't know when that would be. This project was about trying to understand what "later" meant to us.

The other impetus for the piece was that all the Zoom events were not doing it for me. I wanted to explore what it would look like if, rather than trying to stream more of ourselves online, we limited a connection to just text and our imagination. In doing these performances, I found that the act of imagining together was a higher-fidelity experience, and it gave me a more embodied feeling than streaming my digital presence to another person.

You use that phrase, "highest fidelity," in the piece. What does that mean to you? I was imagining it in reference to being with somebody in person, but maybe it’s more about a connection you can feel.

A lot of my work involves interacting with people over video chat, and with that, sometimes it can feel like there’s a barrier hindering my ability to get in sync with someone. But what I realized with this piece is that “fidelity” was not just a matter of having a better internet connection or higher-resolution video. It’s more like a state of mind, or a matter of really being present with someone. It occurred to me that if the video part of the connection is put aside, we could focus on other aspects of presence.

It was also a provocation for myself, like, are in-person interactions always more intimate and meaningful? While I don't think it’s true, it is easier to be present with someone when you're in-person. But it isn’t because of the physicality, necessarily—I think it has to do with where we place our attention and what we're prioritizing.

It's interesting to think about how our relationships have evolved over the course of this ongoing pandemic. Most of us are more deliberate about who we see in person now, and bringing our physical bodies into spaces with other people has become an intentional decision. Do you think this stripping away of default, casual physicality has changed our sense of what's important in relationships?

"Intentional" is a good way to capture it. Over the past year and a half, the status quo of our individual lives was completely disrupted. For many people, it has been a time to question what you're doing with your life, and who you're spending time with. But it’s been tricky. As a shy person, it’s become harder to not feel isolated and alone. There were so many Zoom social events in the early pandemic, and I felt like, “I didn't even like going to social events before, and now... I just can't do this.” So for me at least, nurturing my actual relationships in purposeful ways has become extremely important.

So much of your work is about how we're mediated through technological interfaces and platforms, which is something that the pandemic forced us all to confront, consciously or not. Have you picked up on any broader changes in this phenomenon, as we’ve massively shifted online?

Because of the work I make and also the kind of person I am, I'm always thinking about the unspoken rules that are shaping our behavior, interactions, and relationships with each other. Whether we notice them or not, we’re all constantly making assumptions about other people based on unspoken codes of conduct. With digital platforms, because of the way the technology is built, a lot of those rules get programmatically encoded into the software or into the design. You are presented options to “like” something or “follow” a person, or given certain word lengths for your messages. Or, algorithms bring people into your life by suggesting their profiles to you.

As almost all of our communication has moved online these days, we’ve all become more aware of how these rules and decisions affect us. My hope is that we take the next step in questioning who’s making these decisions and why, and seek out ways to shift the rules a little bit to subvert online spaces. Otherwise, we’ll have to accept this as the new status quo, and we risk not seeing the implications of the limits being placed on us.

I’m curious how you think the pandemic has changed our sense of humanity, especially our relationship with mortality. In your last piece from the Muted Series, Goodnight, you set the prompt to text someone goodnight every night until you die. Why did you address your own demise in such a way?

Over the last year and a half, death has been much more present for all of us. Depending on your culture, belief system, and where you are in the world, it can mean a lot of things—but in the United States, it's not something that most of us think about until we are confronted by it directly. So in a lot of ways, the pandemic brought many of us closer to the idea of dying than we had been before.

For me, this confrontation with death helped me reframe a lot of the decisions I was making in my life. So while some of my friends said of the piece, "That's so intense, you’re going to text someone ‘goodnight’ for the rest of your life?", I thought, "Yeah, but I could be gone next week." Even COVID aside, any of us could be. So I was thinking, "I need to start this performance soon, before I die.” [Laughs]

Over the course of the pandemic, you made five different performances, and with Muted, you've grouped them all together into one piece. Was it tricky to mesh the previous performances together? Or did it feel like a natural way to relive the past year and a half?

Bringing all the performances together into Muted was a way of processing all the works, and all of the emotion and reflection that went into them, on a deeper level. Looking back at texts I'd written while developing the individual pieces, and adding sound, helped me remember what I was feeling at the time, and what the people I was interacting with might've been feeling, too.

Putting it all together was sort of an experiment. I knew I wanted to make a sound piece because being able to walk around and listen to things, and being away from the computer screen, was something that really helped me in the past year and a half. So the audio came first, working with sound artist and filmmaker Chisato Hughes, and then I designed the piece as a screen-based experience as a way to make it more multi-sensory.

I've also been thinking about disability and accessibility lately. In creating the web-based experience, I wanted to experiment with image descriptions, audio descriptions, and captioning. For most of the five performances, I selected one image that I felt represented the piece, and had most chapters open with a text-based description of that image that was written and read by artist and writer Dalena Tran. I got excited about different ways to incorporate more senses into the piece, in addition to the sound itself. So you're listening to something, but you're also hearing a visual description, and you're hearing an emotional description, too.

It’s nice how making the piece accessible was also a way to add more layers and depth.

Yeah. The pandemic has brought up so many questions around illness and disability. I was really moved by an essay that Johanna Hedva wrote, that Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain referenced in their project Get Well Soon. It was about what we do when we're actually forced to confront issues of vulnerability and collective care. Johanna’s ideas got me thinking hard about, “Who actually has access to these spaces, and who do we not see?”

In some ways, being remote improved some accessibility issues. People now realize we need a few more protocols for interacting, instead of just going with mainstream group norms. We also have to be more explicit about inclusion, by doing things like including our pronouns when we introduce ourselves, making sure images are described, and things like that. In this piece, I was trying to think about what I have learned over the past year and a half, and how I can bring that into the work.

As a viewer, what came through most for me was how poetic and full it felt because of how the sounds, descriptions, images, and texts all worked together. It’s a good proof of concept for how making things accessible actually improves the experience overall, for everyone.

Yeah, that was the hope. I was also trying to achieve this feeling of having almost too much stimulus coming in, which was how I felt a lot of times sitting in front of my computer throughout the pandemic. A reference point for this is Carolyn Lazard’s video, A Recipe For Disaster, in which they layered captions and audio over an episode of Julia Child’s The French Chef. You can't actually focus on everything at once, so you have to selectively zone in on one part at a time. My interpretation of the piece is that instead of thinking that disabled people are missing something that non-disabled people aren’t, we should reframe it as, “What if this is all too much information, and we’re all taking in different amounts of it?”

It feels important to acknowledge that we all get equally lost at points in our lives, and that’s okay. Similarly, one shift that happened with my work over the pandemic is that it became much less goal-oriented. I haven’t felt the need to tie things up in a neat package, which is something I used to strive for. So I think this piece is that: something that’s not totally resolved.

Just like the pandemic.

Yeah. I'm just trying to capture some of what’s been going on, reflect on it, and remember it.

As part of the Tech Residency showcase, Lauren Lee McCarthy - Wake Words (2021) is on view at Pioneer Works from October 11 to November 11, 2021. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast