Squatting at the End of History

"Squatting at the End of History" is part of Embedded, a series of writings on the moving image. Artists, musicians, and writers choose a piece of media—embeddable on a web page—and elaborate on why it has lodged itself in their psyche.

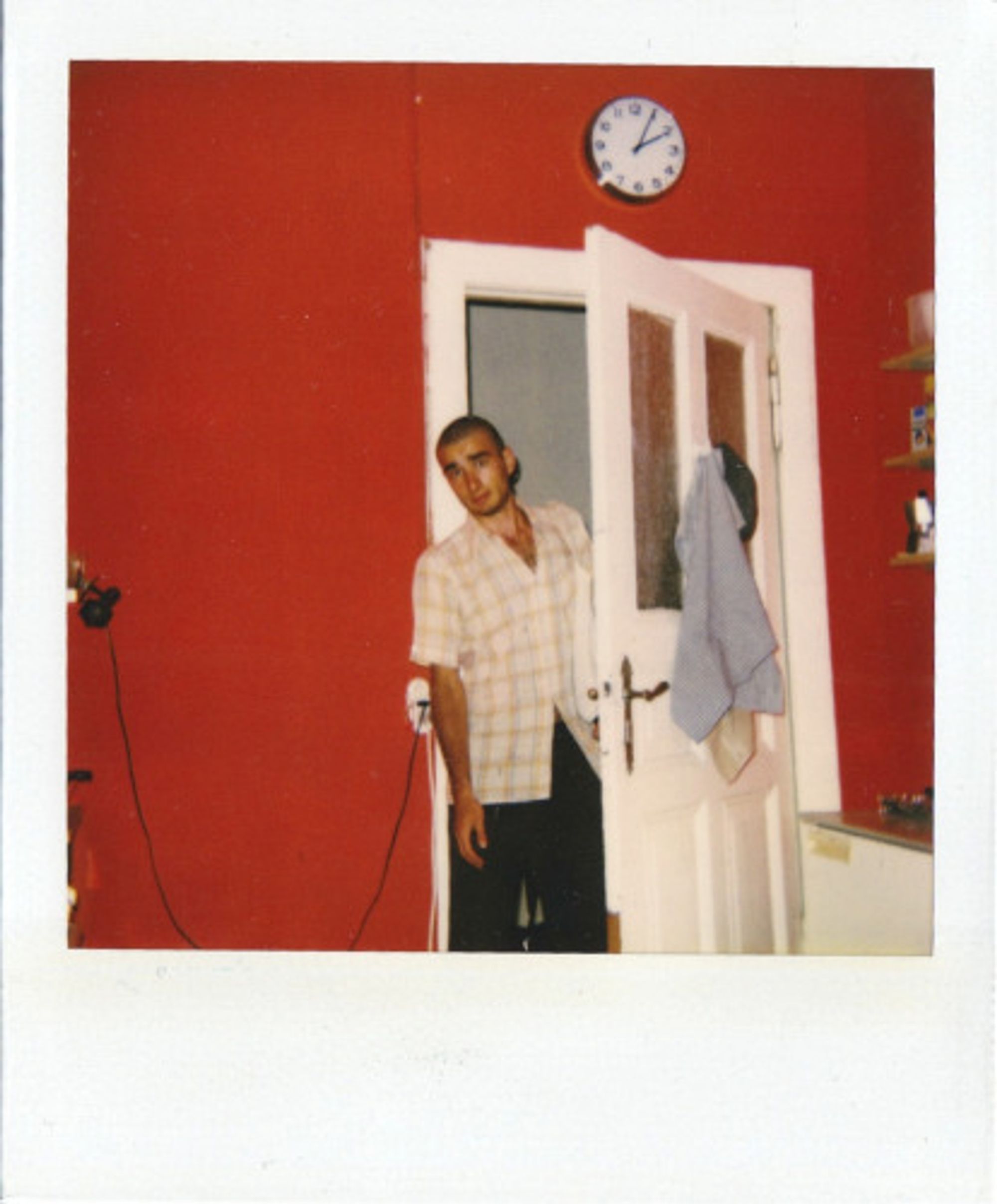

An old friend recently sent me a video that propelled me back to our squatter days in Geneva—an age of 1990s innocence. The video, “Production Artistique des Squatts de Genève” (or “Artistic Production in Geneva Squats”), depicts a squat across town from our own: fellow members in what was actually a very large scene for a small bourgeois city (around two thousand squatters in a town of two hundred thousand). The video shows the squatters among their extravagant murals, poky underground bars, experimental pop gigs, and roomy apartments. We hear them talk about their lives with deadpan sincerity. The clumsy footage will look banal to most, even to some squatters of the time, but it’s painfully charged to me. Watching the video, what I see are versions of myself, and how I must have come across when our own squat was turned into a nationally syndicated reality show.

For a few months, in 1996, our lives in an occupied building were broadcast on a show called Voilà. Unlike the above footage, Voilà is not available online. It’s a rare cultural artifact that lives in the offline shadows. Voilà is prehistoric. Spectral. From a time when a DJ and a bartender could just sit there in the half-light, no phones in sight. The last days of disco: a generation as melody. As long as it remains offline, that innocence is preserved.

Voilà aired once a week before the evening news—prime time. The show offered mainstream audiences a weekly glimpse into the lifestyles of “rebellious youth.” It’s easy to see why the show’s producer was enticed by our squat in particular. We were a textbook assemblage of telegenic twentysomethings: architects and artists discovering the joys of post-structuralism, avant-garde watchmakers, transcontinental jet-setting DJs, overeager humanities nerds like myself, and at least one alleged alcoholic.

We lived among our building’s original inhabitants: two sex workers, both of them in their sixties, still taking customers. They had both lived there since the ’80s (when the place was still a five-floor brothel, right in the middle of downtown), and had only stopped paying rent when we moved in. One of them was polite and slender, with sophisticated pantsuits and a pug. The other was cranky, big-boned and monosyllabic, and wore an enormous red wig at all times. We called her Mozart. We were 20 little smurfs, 20 different lifestyles. Racy and Queeny, Geeky and Freaky: you are free to guess which stereotype your trusted writer fulfilled.

In the ’90s, there seemed to be more at stake in television than there is today. It wasn’t easy to talk TV without stirring up a strident opinion. TV as the future. TV as the past. TV as mass conformism. TV as popular critique of the elites. It was the medium of choice; just as monumental as the internet is today, but already charged, at that point, with a good half-century of impact. Although I was a student at the time, devoted to homework and little else, the first thing I said on camera was, “I’m working on a novel.” Don’t ask me why. It just seemed like something a self-assured person would say. Like some people say they’re “investing in stocks,” or “taking time off to be with the family.”

The Voilà crew followed us around as we painted walls, did the dishes and complained about one another. Off camera, they encouraged this bickering—anything to spark the interest of a prime-time audience. So hey. Any idea why X looks so frustrated? Hey. Y says you don’t clean up after yourself. Do you agree? Kind of a strong accusation, if you think about it. Oh, and they said you have problems with Z. Why does she irritate you so much?

Voilà was one of the first shows of its kind. An early milestone. Historic. Second to The Real World but well before Big Brother. The crew dropped by for just a few hours at a time, so it wasn’t exactly nonstop surveillance and social media lynch mobs, even if the show was laying the groundwork for just that. Such were the ’90s. We paved what many might consider a path to ruin, heading straight for those colorful catastrophes to come.

Compared to the bohemian charm of the “Production Artistique des Squatts de Genève,” our own squat was a bit more techno and polyester. But these are cosmetic differences. There was the same critical yet comfortably ironic attitude, the same perennial sleepiness at endless kitchen tables, the same ubiquitous plumes of tobacco smoke, the same gigantic espresso percolators, the same charismatic mix of assiduous and scruffy, civil and stroppy—all adding up to the very same ’90s nonchalance.

It may have not immediately occurred to us then, but the zeitgeist was overwhelmingly sympathetic to our happy-go-lucky generation. The fact that mass media was so supportive of our rebellion clarified perfectly well, even to us rebels, how subversive it actually was. But these were, to state the obvious, different times. Back then, a video call was akin to time travel. We were comfortable in our time, confident in our role. The squats embodied the strange mix of youthful alternatives and ironic detachment. We had distanced ourselves from the television sets of our parents’ generation and minced those grainy black-and-white beliefs to quicksand.

Young people nowadays, the ones I teach at college, they don’t fuck around. For all their tattoos, they are surprisingly professional. There’s little left of the buoyancy we took for granted. They are used to being recorded, performing on camera. Last year, the college where I used to teach threw a ’90s-themed party. I considered sending my students this YouTube video, or the Voilà collection on VHS, which my cousin had located in the mid-2000s, to everyone’s delight. (My mother, upon watching, had laughed until she cried.) They might have recreated our looks, our nylon shirts and bucket hats. But fashion is the smallest part of it. What’s impossible to replicate is the state of mind. The posture. That rare ability to smile like time is on your side. To walk and talk like your sense of irony and the welfare state will somehow conspire to see you through. These were the perks of the end of history: a brute sense of dayglow optimism—one that’s pretty unlikely to appear again. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast