Frank's Lake

“Frank's Lake” is part of Embedded, a series of writings on the moving image. Artists, musicians, and writers choose a piece of media—embeddable on a web page—and elaborate on why it has lodged itself in their psyche.

A fish with a telephone in a mountain lake taught me to not leave the faucet on if I’m not using water. It’s hard to know when I first saw Sesame Street’s “Water Conservation” since it premiered when I was two years old, but it left a lasting impression. In the video, a fish named Frank lives in a reservoir next to a house where a boy named Carl is brushing his teeth and getting ready for bed in the bathroom. As Carl absentmindedly lets the faucet run, water drains directly from Frank’s lake to Carl’s sink. Frank phones Carl, who picks up and says, “How are you?” “A little dry actually,” Frank replies. “Could you turn off that water when you wash and brush your teeth?” To this day, seeing water run without purpose gives me acute anxiety. I still imagine Frank nervously watching his life-source drain away around him.

Frank the fish’s plea feels all the more urgent today, but when it first aired, in 1990, it spoke to a specific moment of environmental consciousness in America. The animation of the early ’90s also brought my generation Captain Planet and FernGully, both of which warned against environmental impacts of rapacious global capitalism (not that they called it that.) These cartoons raised awareness of international issues like deforestation and pollution but didn’t necessarily include a critique of larger economic systems decried by turn-of-the-millennium movements such as the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization in Seattle. Captain Planet and FernGully also targeted a slightly older audience than Sesame Street, incorporating popular pre-teen tropes like superheroes and magic. Klasky Csupo, the animation studio responsible for “Water Conservation,” also made the popular ’90s cartoons Rugrats and The Wild Thornberrys, which are recognizable for their mildly grotesque style of clashing color schemes and bulbous-headed characters. Peter Chung, the director of “Water Conservation,” also worked on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles television show and Æon Flux shorts. While the style—and the landline telephone—dates the video, there’s a simplicity to the scene and narration that keeps it from feeling stuck in time.

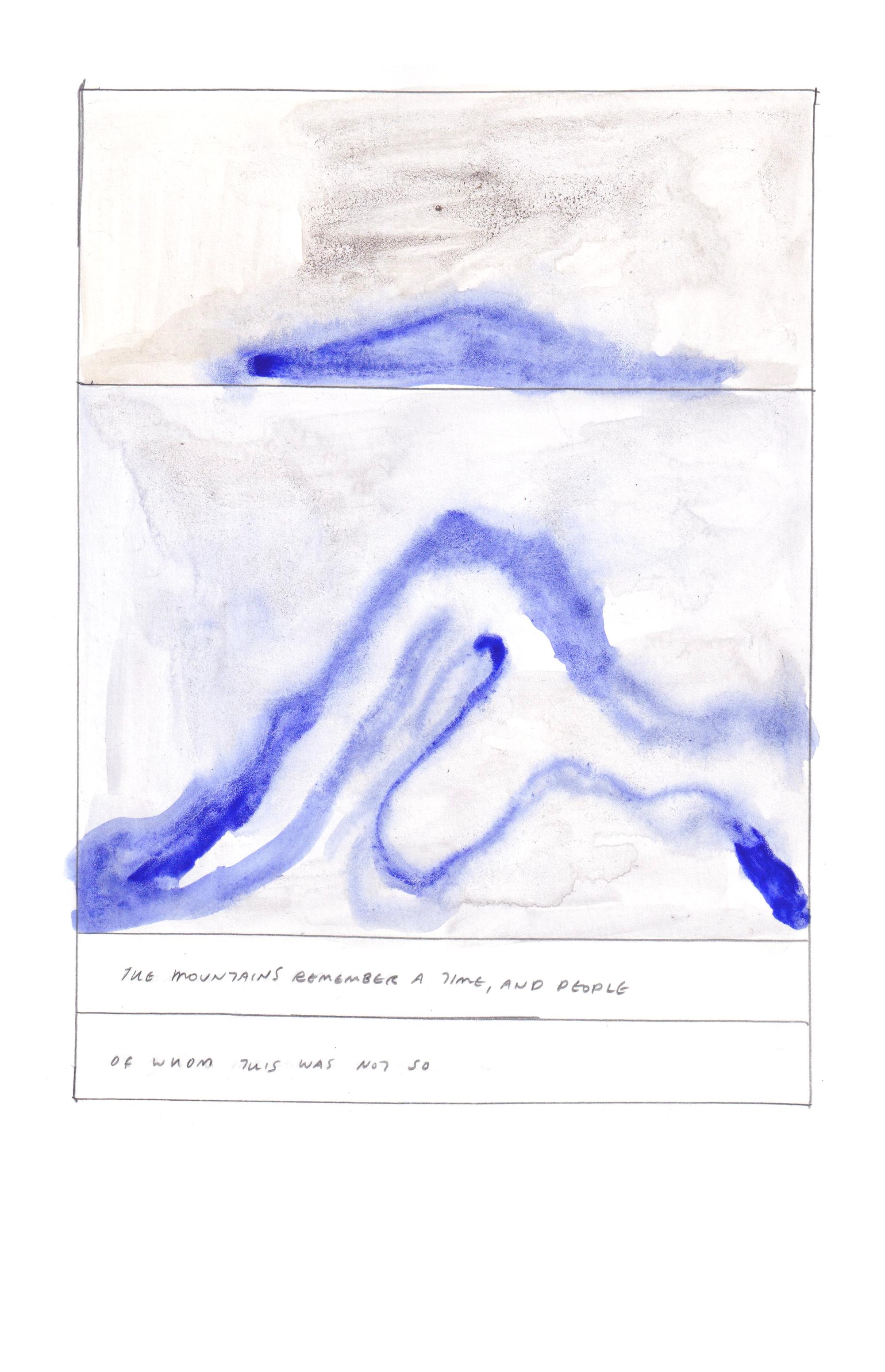

In 2023, Frank’s lake could be one of the many Western reservoirs fed by the Colorado River that have seen a visible drop in water levels from increasing usage and decreasing replenishment. Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, and parts of Mexico all depend on Colorado River water; as snowpack in the Rockies becomes less abundant and predictable due to climate change, the lowering water line becomes a concrete measurement of crisis. Despite negotiations between these seven states and federal government to temporarily reduce usage, long-term regulations have now been delayed to 2026. Until then, untangling the one-hundred-year-old “Law of the River,” which legally could see Arizona receiving almost zero allotments before California gives up any, will be no less of an uncomfortable task.

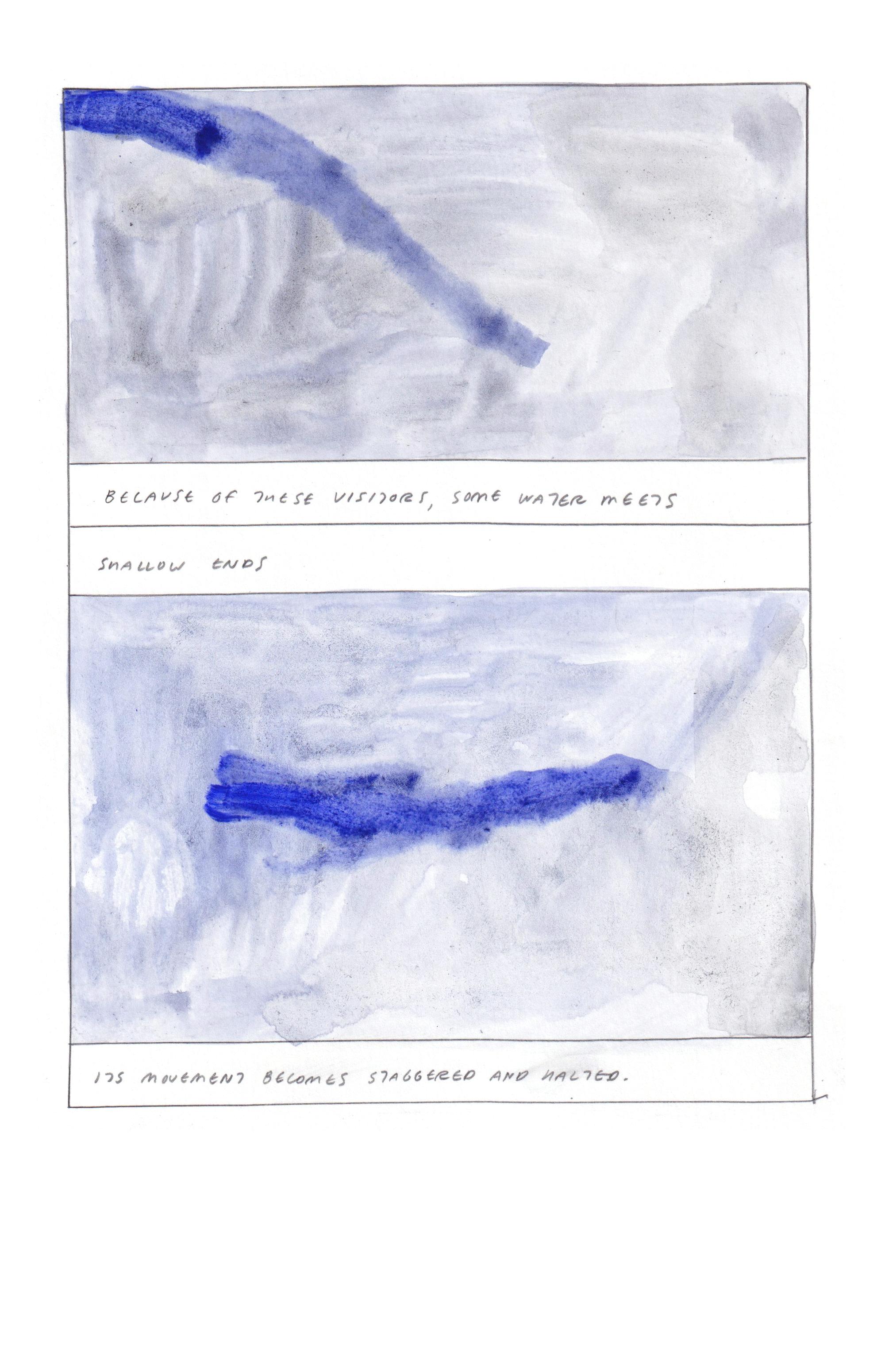

Frank could also represent any number of fish species that are feeling the effects of careless water management. For fish, reservoirs themselves have been a huge problem, even before their water lines started dropping. Legal battles to restore rivers to their wild state by removing dams have been an ongoing imperative by Native American tribes like the Klamath Basin Tribes and Upper Skagit Indian Tribe in Oregon and Washington. Not only has the widespread damming of America’s rivers impeded and interrupted ancient cultural and spiritual connections to water and animals, the practice has also devastated the rivers’ ability to support a sustaining supply of fish. Factors such as sudden changes in flow, lack of shifting debris, temperature increase from stagnation, and adaptations in predator behavior all greatly affect fish that have evolved over millennia in water that freely moves.

Rewatching “Water Conservation” as an adult, I recognize that the issues around this topic are much more complicated than the video’s simple moral. Combatting environmental ruin is more complex than “don’t waste water.” Yet the messaging of the video—and its emphasis on water as a tangible and finite resource—remains effective. Unlike global climate change, which can be hard to see or pin to specific events, crises related to water are extremely local, specific, and easily measurable. Access, abundance, and threats to freshwater also vary greatly. Especially for rural regions dependent on direct access to groundwater—like many of those near me in the Mojave Desert—choices by individuals and communities can have a direct impact on the lives of other people who share the same watershed or aquifer.

Effective water conservation requires large-scale political action and policy, but animations like this are still successful at furthering important concepts. “Water Conservation” was part of Sesame Street’s large breadth of educational shorts, which commissioned artists to make stop-motion, claymation, hand-drawn, and early computer-graphic animations to playfully teach children simple lessons about themselves and the world around them. It’s also key to mention that Sesame Street was founded by Joan Ganz Cooney to try to mimic the style and impact of TV ads on children. “Water Conservation” was just one of the ecologically oriented animations that influenced me when I was young. Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the devastating 1978 rendition of Watership Down, and Disney’s The Fox and the Hound all had a profound impact on my interpretation of how humans could relate to other species and the natural world. Yet, nothing’s stuck with me quite like the image of Frank’s lake draining down the sink.

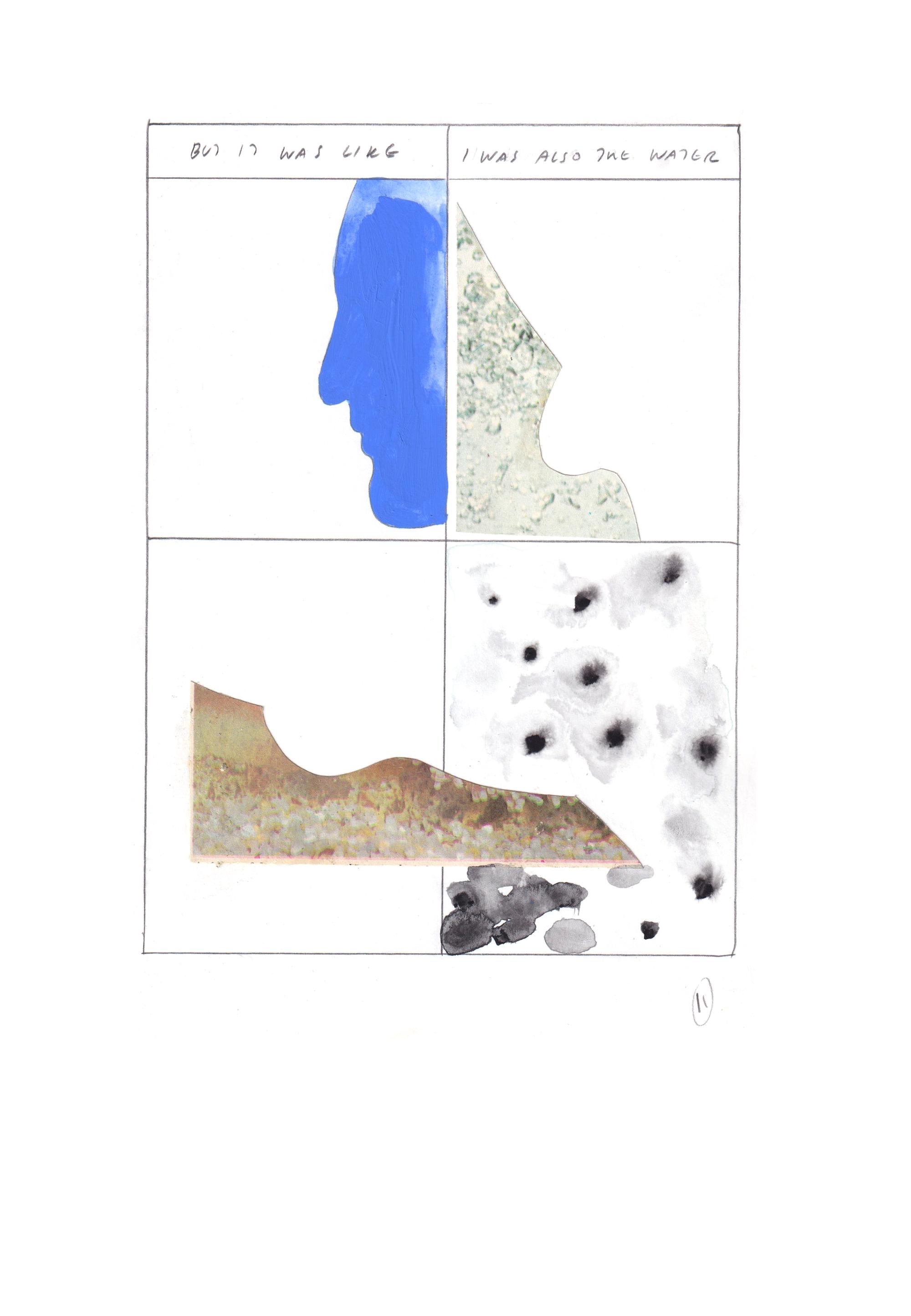

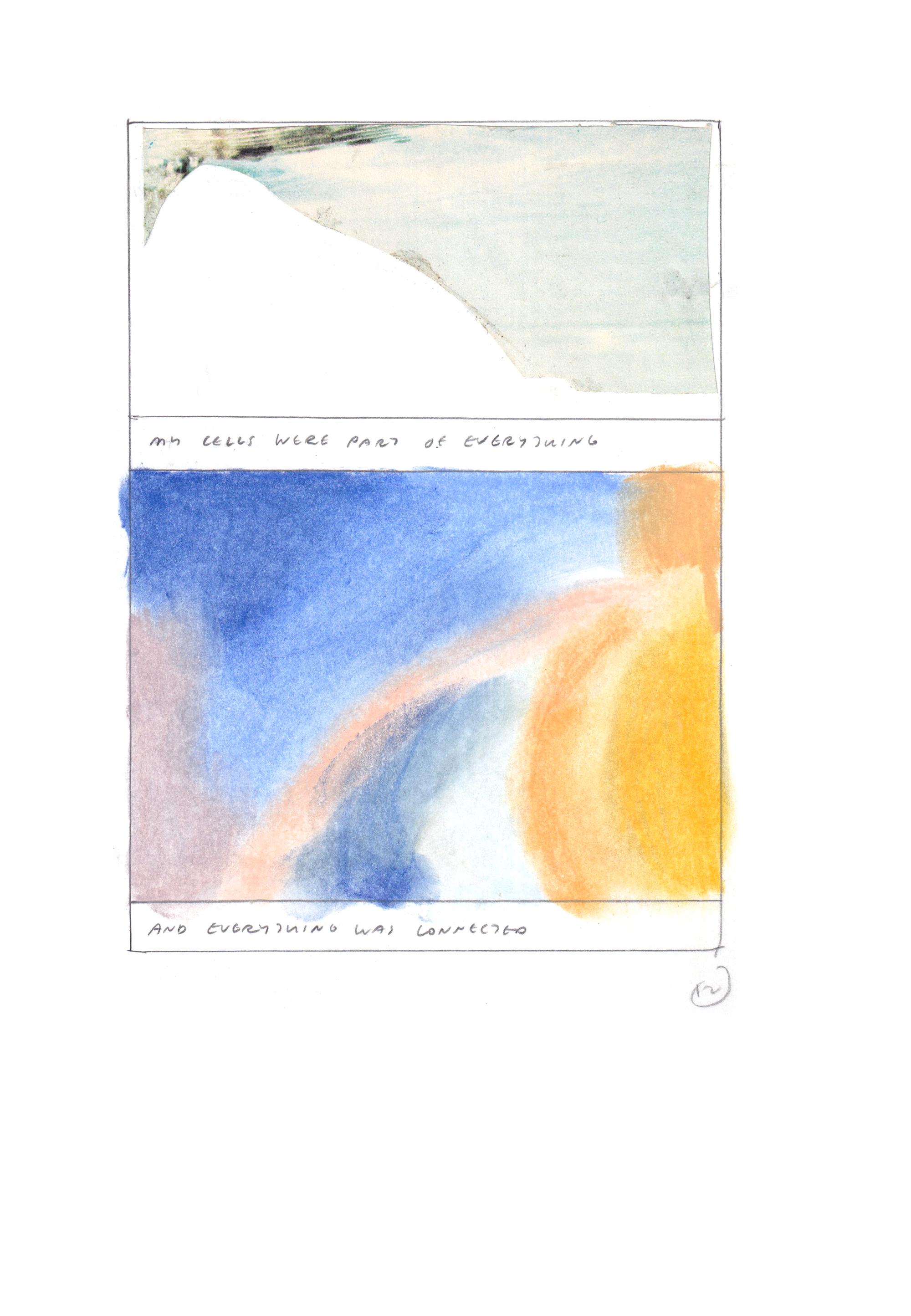

Now that I’m a working artist myself, “Water Conservation'' reminds me that art can function as direct education. As calls for mobilization grow in response to dire circumstances for land, air, water, and living beings (especially the most disenfranchised of our own species), the messaging of activists also needs to diversify. While there are no clear models, I often try to convey this sense of urgency, and consider how my drawing practice can fit into larger ecological storytelling. This includes attempting to adopt nonhuman perspectives within my graphic novels and facilitating interdisciplinary educational experiences through my project the Institute for Interspecies Art and Relations. Although it is difficult to calculate the larger cultural and societal impacts of environmental art and education, the ways artists have shaped my own thinking assures me they are crucial.

In the final seconds of “Water Conservation,” after Carl understands the impact of his behavior, he promptly responds by turning off the faucet. “Sorry,” he says to Frank. “How’s that?” “Good,” Frank replies, relieved yet with a note of distress still in his voice. While good may not be perfect, it may be the best starting point we have. ♦

Excerpts of Aidan Koch's story Man Made Lake and Spiral, from the forthcoming collection Spiral and Other Stories:

Subscribe to Broadcast