My Daughter Was Laying Eggs

"My Daughter Was Laying Eggs" is part of Embedded, a series of writings on the moving image. Artists, musicians, and writers choose a piece of media—embeddable on a web page—and elaborate on why it has lodged itself in their psyche.

As a psychoanalyst, my day to day centers on the obscene—the scene behind the scene, the profane and unacceptable that can only be uttered in a private room, below the whirring of a white noise machine, to a witness sworn to secrecy. When I leave my office I enter again into the world of polite society, which is filled with media that promotes neatly packaged narratives about who we are and what we want, as if these things could be so easily known. The conflictual, nonsensical, and vulgar are kept out at all costs. It’s rude dinner party fodder, for instance, to suggest someone is afraid of being trapped in their mother’s anus or is spiraling because they're identified with shit being flushed down the toilet. And perhaps it is this stark division, between what is permitted inside and outside of the office, that accounts for my double take when I stumbled into the world of Mani Mani People. In this dark, strange wormhole of an English dub manga series, the grotesque and paradoxical logic of the unconscious reigns.

This series, though especially popular in Japan, is watched worldwide; Mani Mani People has received 1.4 billion views since the channel was created in 2019. The manga stars a man named Mr. Moroboshi—an “entrepreneur slash scientist slash doctor” and patriarch of the Moroboshi company, hospital, and family. He stands in as an ideal self for a less fortunate cast of characters who suffer from strange afflictions, phobias, and perversions galore. The show’s cutesy, cookie-cutter graphic style is a striking contrast to its extreme subject matter, which ranges from body-swapping and shrinking men to uncontrollable farting and hairy tongues. The characters often enter states of unbearable arousal. It’s the stuff that is banished to the far recesses of porn sites, or the analytic couch or the nightmare, yet here, on YouTube, is fully elaborated—in peppy, cartoon detail.

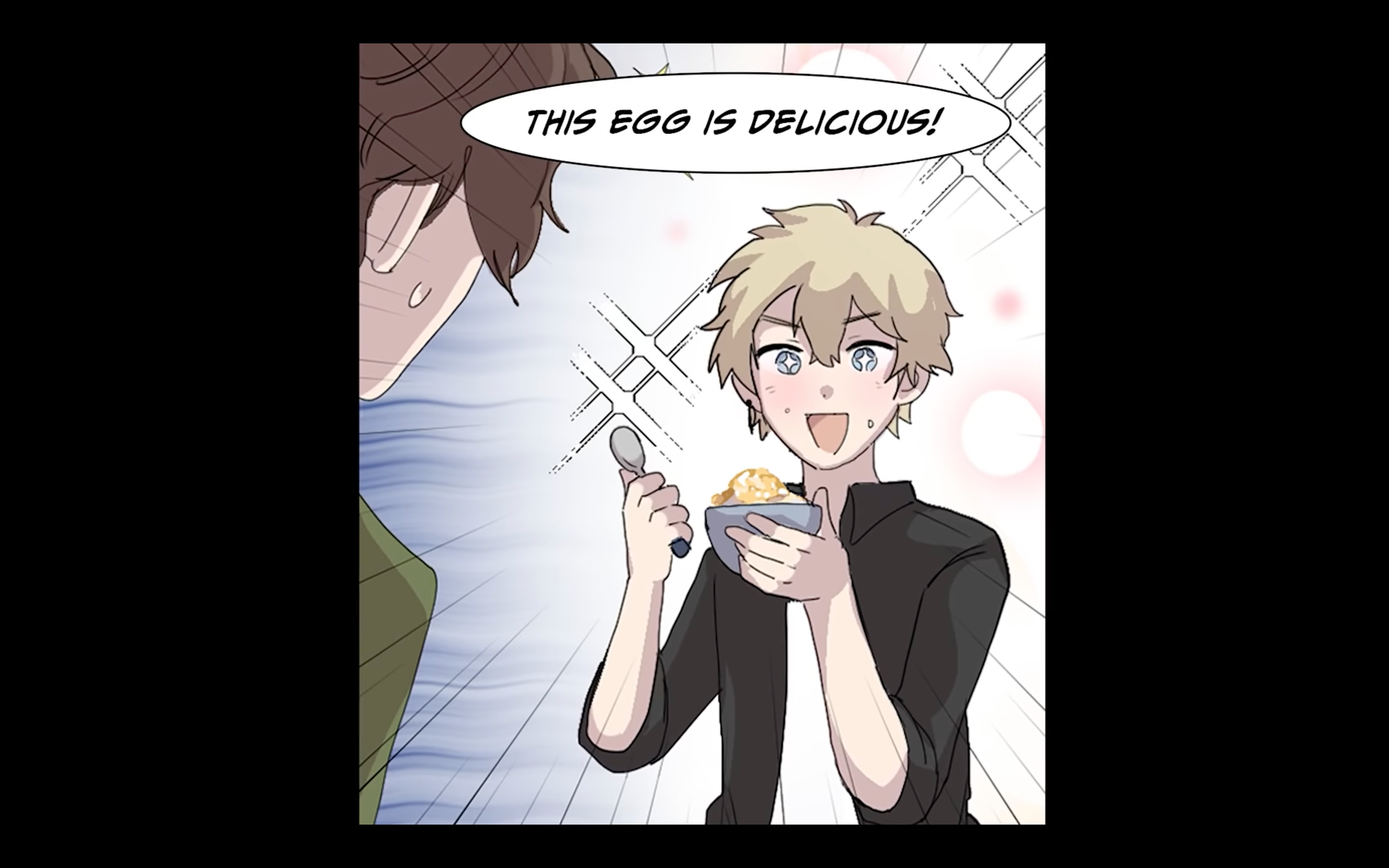

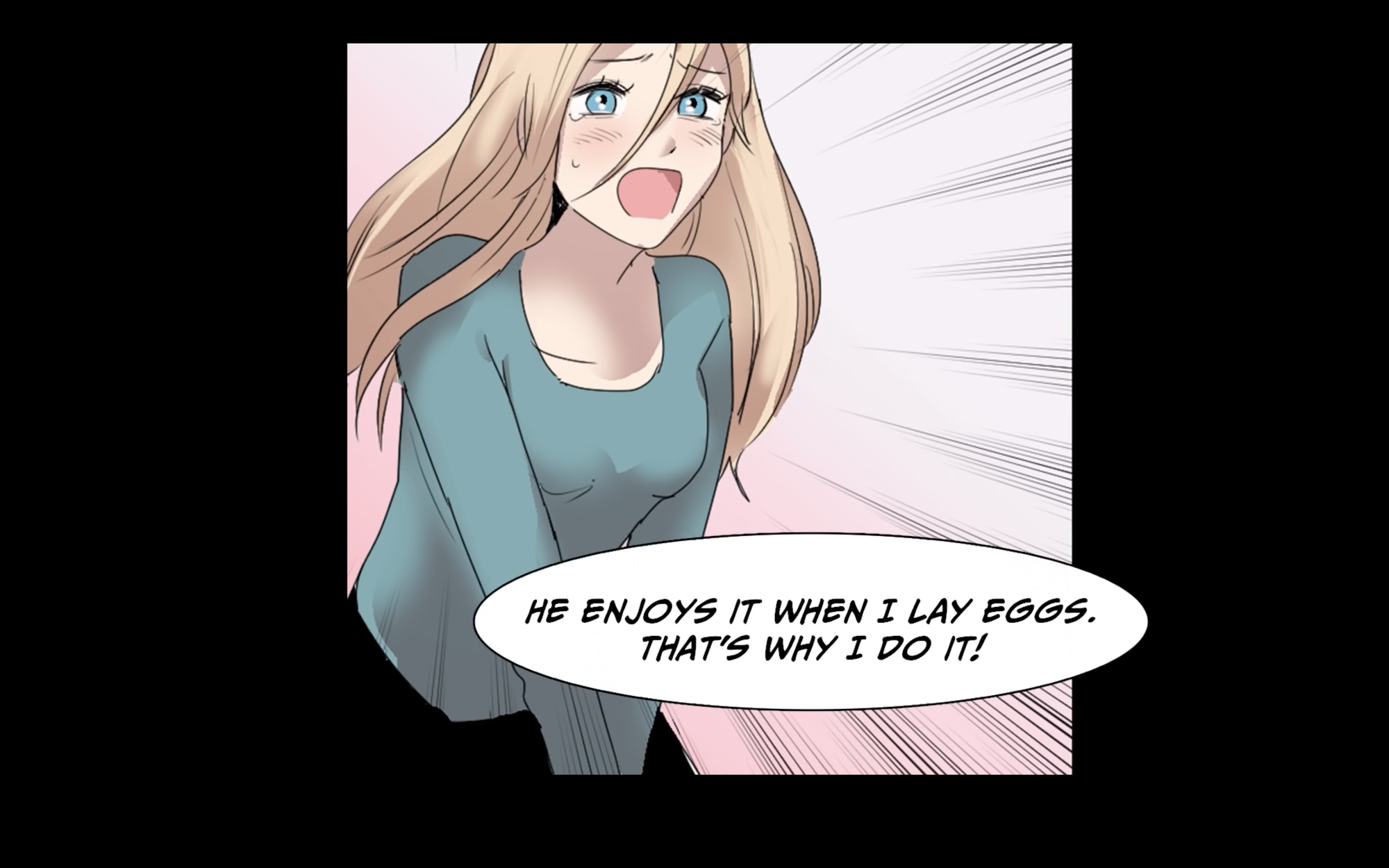

As I’ve delved more deeply into the series, watching and rewatching episodes, I’ve grown convinced that there is little in contemporary culture that so tellingly—and whimsically—evokes Freud’s theories of our sexual unconscious. The word “manga,” after all, comprises two Japanese characters that translate as “whimsical” and “pictures.” Here, at the meeting point of the cute and the abject, the comedic and the repulsive, the unconscious gets its time in the sun. In one of my favorite episodes, “My daughter was laying eggs...! This is why…,” a truck driver named Mikai comes home to find his fourteen-year-old daughter, Lisa, screaming and panting in her room. Lisa, it turns out, is laying eggs. She’s ashamed, but her father is fascinated. So much so that he steals one of her eggs and gives it to a coworker, who cooks it sunny side-up and finds it “delicious.” When Lisa’s egg-laying persists, Mikai takes her to a skeptical surgeon who accuses the father of inserting the eggs himself. Lisa finally comes clean: after Mikai witnessed Lisa’s mother die in a car accident, he developed multiple personality disorder. Lisa fell in love with one of the personalities (named William) who enjoys watching her lay eggs. After the truth is revealed, father and daughter are placed in separate mental clinics. The episode closes on a scene of Lisa begging the doctors not to “fix” her dad, as she can’t live without William. This fable reads like a roundabout response to a child’s questions about reproduction: what does it mean that there are “eggs” in a woman’s body? How did they get there? Can you eat them? Does the father know about the eggs and want to watch the daughter lay them? If the mother dies, can the father and daughter be together?

These are the kind of questions that Freud brings to public attention in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, first published in 1905 and revised repeatedly through 1924. His second essay, “Infantile Sexuality,” introduces the idea that the instinct for knowledge coincides with the first peak in the child’s sexual life, typically between the ages of three to five. This instinct is attached, though not exclusively, to early questions of birth, sex, and later, sexual difference. Freud calls this “the sexual researches of childhood,” an exploration that is carried out by the child alone. Before encountering the question of the difference between the sexes, Freud proposes, the child faces the question of their origin, and the related threat of displacement by the arrival of another child. The discovery of this threat leads to our first fundamental riddle: where do babies come from?

Freud tells us that children often theorize babies are cut out of the body, come out of the breast or navel, or are produced by a special kind of ingestion and defecation. The theories of the Mani Mani characters are more advanced and elaborate, although equally fantastical. As children find the tale of the stork unconvincing, perhaps the medical description—an egg fertilized by a sperm—is just as unsatisfying an explanation for the adult. As we grow older, perhaps "sexual research” continues, with no less absurdity, from the same wellsprings of instinct we can observe in early childhood. Mani Mani characters take research seriously, through tools and procedures: they observe sperm under microscopes, use X-rays to see inside the body, and conduct experiments to determine things like whether women can get pregnant in swimming pools.

As the series encourages us to conduct sexual research, it also takes us on a tour of the classic erotogenic zones. As Freud writes in the third essay in Theory of Sexuality, “The Transformation of Puberty,” each zone is tied to a psychosexual developmental stage, to particular libidinal instincts that relate to each other and to the desired object. In the oral stage, for instance, the erotogenic zone is the mouth and involves the instincts of sucking, swallowing, and spitting. The Mani Mani characters journey through these zones: the oral (“The girl who was a kiss addict...”, “An incapable couple who licks each other's wounds, too dark and disturbing!”); the anal (“A medical mistake makes her defecate through her mouth...”, “His girlfriend cleans the toilet with his toothbrush every day...”); and the scopic (“What happens when you get hooked on blindfolds?”, “I could see everything that my neighbor was doing through her window...”). Yet the characters in these videos never reach the final developmental phase of sexual organization articulated by Freud, when all the components come together under the single erotogenic zone of the genitals. Perhaps this is the truth of sexuality, and “adult genitality” as Freud envisioned is itself a fantasy of maturity that we never reach.

Still from My daughter was laying eggs...! This is why... [Manga dub].

Courtesy of Mani Mani People.

Still from My daughter was laying eggs...! This is why... [Manga dub].

Courtesy of Mani Mani People.

Still from My daughter was laying eggs...! This is why... [Manga dub].

Courtesy of Mani Mani People.Often, I hear from my patients about powerful fantasies concerning a perfect sexual relation—the idea that if they just met the right person they would be able to eradicate disgust, severing it from lust and attaining total satisfaction. People attempt to ward off what Gen Z calls “the ick,” a term to describe when initial attraction to a person suddenly flips into repulsion. In Mani Mani People, the ick factor is dramatized, perhaps so that sexual research can continue. The videos suggest that arousal and disgust may not be as divisible as we think.

Like pornography, the characters in Mani Mani People function as recognizable roles and archetypes: fathers and daughters, doctors and patients, girlfriends and boyfriends. Whereas in most porn a familiar relation is set up and then enthusiastically transgressed, Mani Mani People sets up such premises in order to maintain the tension, which allows the plot line to continue. There are no portrayals of genitals in Mani Mani People, but it feels, in ways, far more pornographic than live action sex ever could be.

It would be easy to read a preference for animation as part of a trend of rejecting the “real body” in favor of simulated perfection. But perhaps sexuality, as it originates from our infantile imaginations, has always been cartoon-like—exaggerated, satirical, untethered to reality. These fantasmatic scenes—of vomit, urine, breastmilk, feces, body fat, pus, semen, sweat, saliva, and blood—become a parade of the earliest wishes and fears that structure our so-called civilized lives. The unconscious, like the seemingly endless scroll in the bowels of YouTube, never stops producing fantasies and defenses against these fantasies. Perhaps we would do well to emulate the anonymous creators of this series, who wittingly or not, have joined in Freud’s project: to set aside moral injunctions, embrace the disgust, and become curious about these fantasies—since they aren’t going anywhere, anytime soon. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast