13 Ways of Looking: Jeff VanderMeer

My new novel Hummingbird Salamander is written from the point of view of Jane, a security analyst who has been gifted with a taxidermied (extinct) hummingbird by a dead eco-activist named Silvina—a woman she does not know. As the mystery deepens and Jane’s investigation gets her into trouble, we come to learn more about the antagonists: the wildlife trafficker Langer, Silvina’s father, a wealthy industrialist, and “Hellmouth,” an agent of chaos who both helps and harries Jane at every turn. At stake in this exploration of eco-mystery may be the fate of the world.

The process of writing Hummingbird Salamander has blurred and reconfigured the lines between fiction and nonfiction, inspiration versus collaboration, in what I think are interesting ways. What the reader hopefully finds in the novel is a compelling and fast-paced eco-thriller with elements of a psychological thriller with conspiracy elements as well. But, for me, it’s also been a fascinating journey both literally and figuratively—which these images demonstrate.

Given the protagonist of the novel, “Jane,” lives in the Pacific Northwest, I used my last West Coast book tour, for Dead Astronauts, to learn more about an area I’ve visited frequently and love almost as much as Florida. I had a few guides along the way, including Seattle’s urban naturalist Kelly Brenner, who took me to places both wild and wildly compromised, like this conservation area under an overpass. I was struck by the confluence of the concrete and the native plants, the way in which they’d built the overpass so sound was more dulled than I’d expected, and how used to that environment the ducks and other birds had become. Hummingbird Salamander includes scenes in true wilderness, but also many of what you might call transitional spaces or spaces that are kind of crumbling in both their human usage and their use by wildlife.

For the purely wild aspects of the novel, I became indebted to Damaris Brisco, who has done a wonderful job as an advocate for Roy’s Redwoods, in California. She was extraordinarily kind in showing me around a beautiful ecosystem, which included an unexpected wild mouse popping out of some moss. The confluence of moss, lichen, and trees, the sense of calm, is something I conjured up for the backdrop of parts of the novel, as a counterpoint to the narrator’s desperate situation. But, also, Damaris gave me an up-close view of salamanders and, later, information on sightings of mythical enormous salamanders of the Northwest that went into the novel.

Jane’s journey down the West Coast is often fraught and paranoid and isolating. She thinks she’s being pursued by Hellmouth, who I mentioned in my intro, given what she’s found out about Silvina. So, I kind of method-acted my way down the coast, trying to see the world through Jane’s fractured and paranoid point of view—that I was being tailed, that I had to be aware of people around me at all times. I hugged the coast in desolate places on the drive from Seattle down to San Francisco. It was cold and lonely at times, in a way that I was drawn to. There were long and harrowing segments, while staying in sometimes unusual and eccentric motels—which I stayed in to mimic Jane’s caution in basically staying in out-of-the-way places. One night I wound up in a very suspect motel. It was freezing and when I got to my room, exhausted from a ten-hour drive, I found a space heater glued into the wall, in a way that I’m fairly sure was not up to code. This photo I took in a frazzled moment kind of summed up the confusion and kinetic energy I wanted for Jane’s journey.

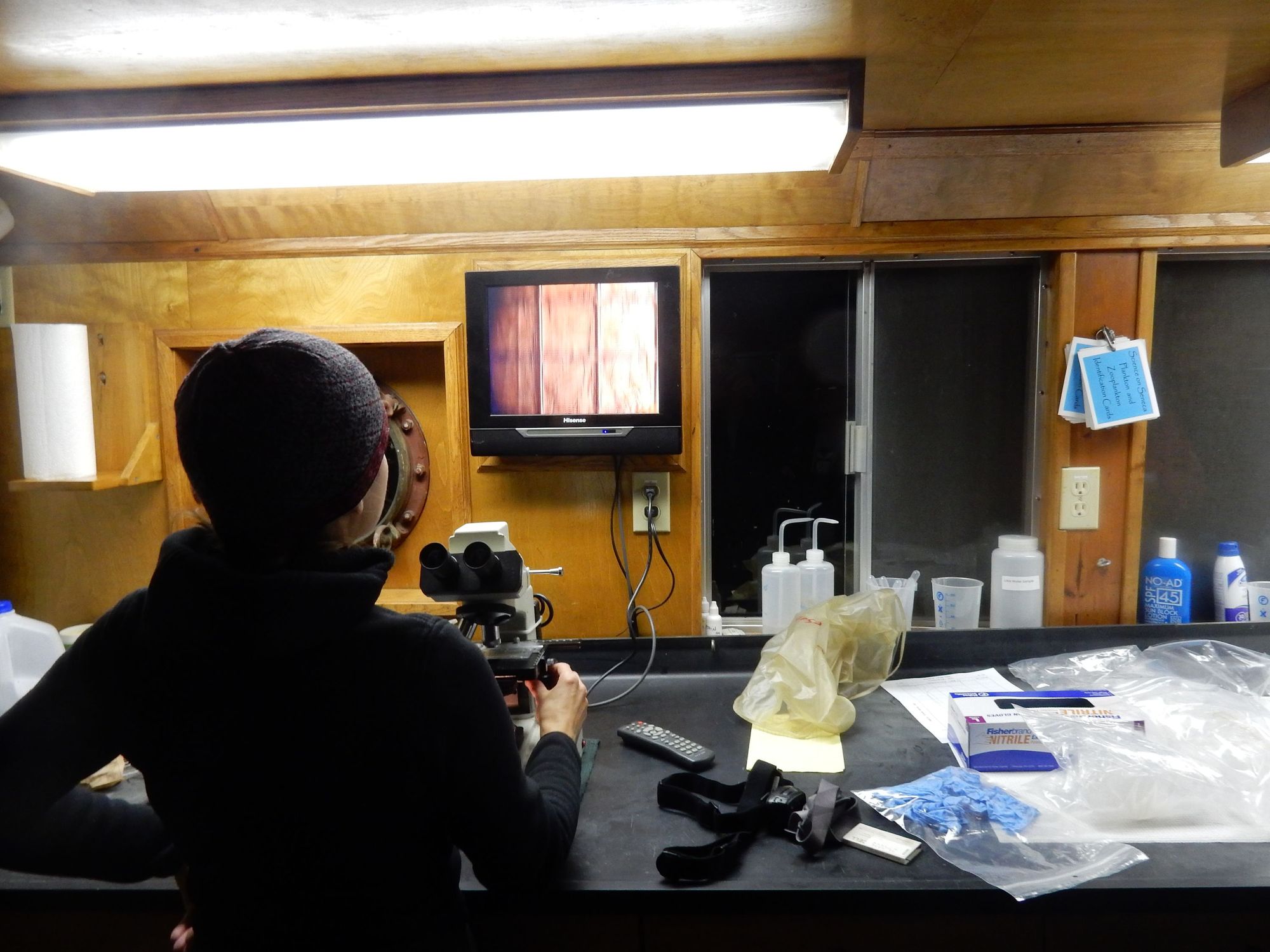

But, also, to go back in time a bit…another formative part of Hummingbird Salamander (and a more orderly, rational one) came from spending a semester as the Trias Writer-in-Residence in 2016-2017, at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. There were so many ways in which my wife Ann and I found it life-changing. But one especially magical moment occurred when biologist Dr. Meghan Brown invited us on a night-time trip aboard the HWS research vessel on Seneca Lake, with students doing research on invasive species. With the catalyst of an introduction from professor and writer Melanie Conroy-Goldman—whose kindness during our HWS trip also influenced the novel—Dr. Brown and I began to talk about the confluence of fiction and nonfiction. These conversations led to her agreeing to create the entire lifecycle and details of the imaginary hummingbird and salamander for the novel. This gave me an interesting constraint and more narrative possibilities than if I had done research and come up those details myself. Sometimes, it’s best to go to source and not try to fake it yourself.

At the same time, I spent a jarring night at the other end of Seneca Lake volunteering to band Saw-whet Owls. I couldn’t help but notice the similarity between the banding process and tales of human alien abduction, and while I see the point of banding, the condition of the nets and the later information I found about how, in fact, larger owls predate on confused Saw-whet owls upon their release… and other disturbing data on how these kinds of collection situations have life-altering effects on the subjects… well, let’s just say it began to suggest fiction. Also suggesting fiction was how a neighbor called the police on our banding operation, claiming our host was cooking up meth, but really just concerned by the late-night noise of fake owl calls to bring the Saw-whet owls to us. Not only did we have to explain to the police that we weren’t cooking meth, but after they left and I attempted to leave, the neighbor actually pulled up in the driveway, and I had to jump out of the way, blinded by the headlights, then quietly crawled through a ditch to my car, wanting to have no part of the impending conversation back at the host’s house. Some of this made it directly into my novel Dead Astronauts, but the general idea of how we treat animals even in situations that seem benign and all the human complications that occur made it indirectly into Hummingbird Salamander.

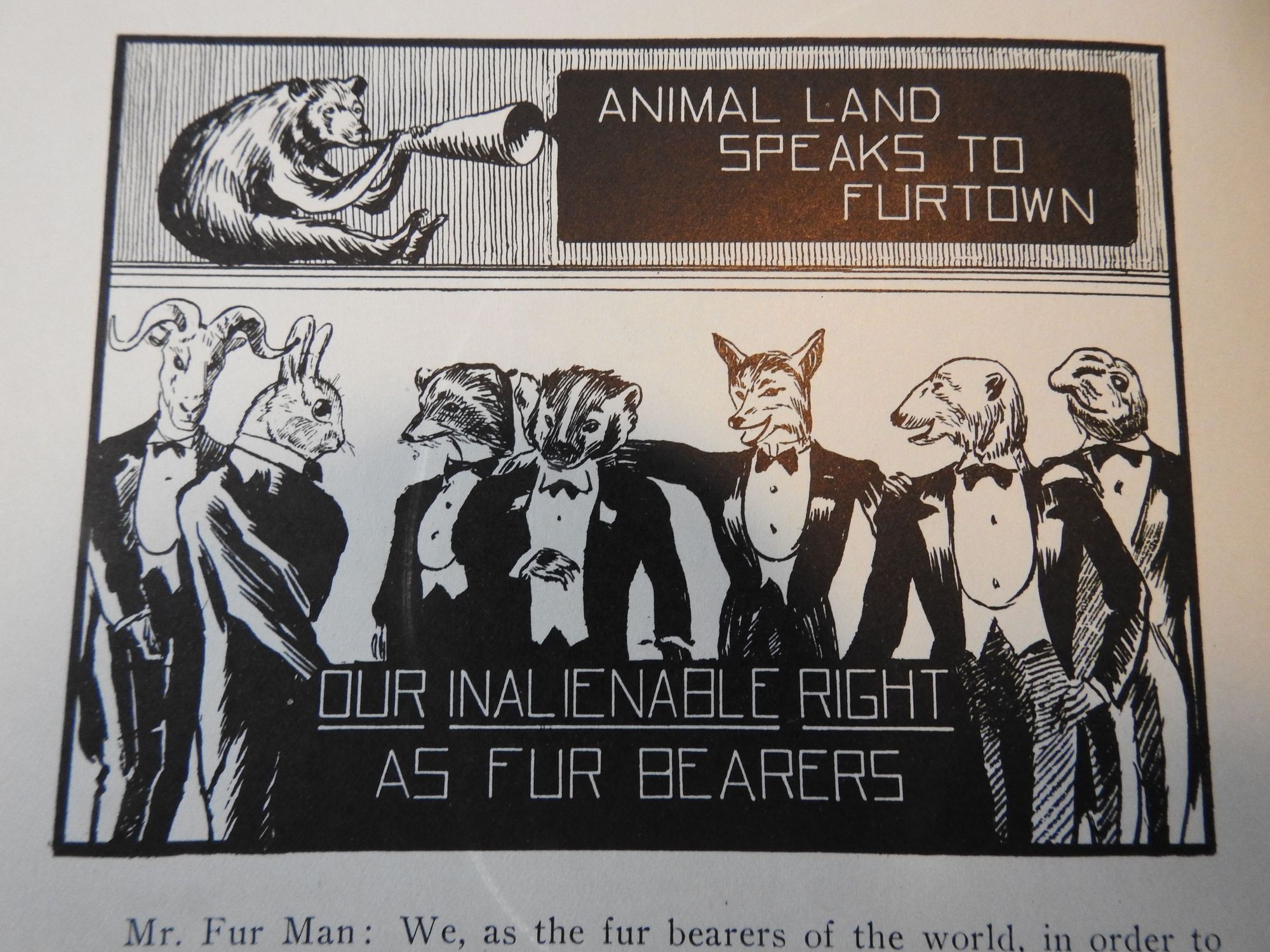

Converging with all of this was something older: a book I found for a dollar in a used bookstore in Minneapolis back in 2009. Oddly Enough: From Animal Land to Furtown from the 1930s had been commissioned by a fur company as propaganda to support the use of furs. As such it had the most outrageous concept for the introduction and as a running theme: that animals actually love to be turned into noble furs. The book is grotesque in how it lays bare this foundational idea that we also see in signs of happy pigs promoting barbecue joints, for example, but taken to an extreme. I bought it because I knew it would wind up in a piece of fiction, and, in fact, Jane finds a copy of this book and buys it and quotes from it, while exploring the mystery of why a dead eco-terrorist has gifted her with some odd taxidermy. It had the same off-kilter vibe as the Hellmouth character and I thought the quotes pointed out something about how we view animals that nothing I could make up could do better—much as it made more sense for Dr. Brown to create the hummingbird and salamander.

Closer to home, the frosted flatwood salamander (nymph stage shown) was my entry-point to the world of salamanders for the novel. The flatwood salamander is native to North Florida and found mostly in a few ponds in the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge. I’ve tried to help with conservation efforts with substantial donations from Annihilation royalties to fund interns and conservation efforts. At one time, I thought Hummingbird Salamander would be partially set in Florida, but when it moved to the Pacific Northwest, the salamander became an imaginary one. And, yet, my personal experience of salamanders is still the local one, and some essence of that still ghosts through the novel, despite the change in setting.

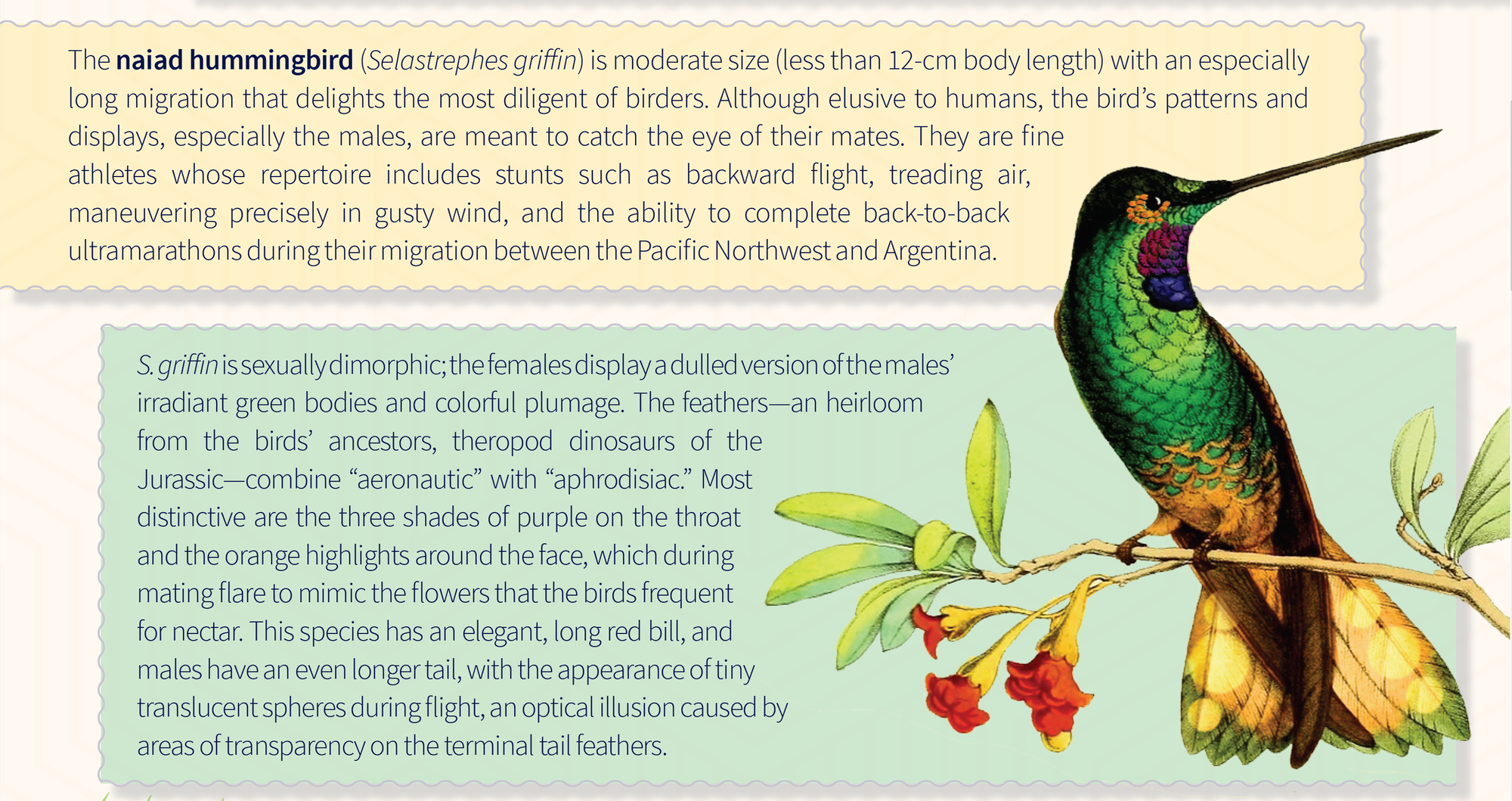

As the real began to merge with the imaginary world of a novel, where fact becomes something other than “information,” the hummingbird and salamander Dr. Brown created for Hummingbird Salamander also took on a meta reality. My frequent collaborator, Jeremy Zerfoss, worked with Dr. Brown to find a public domain image of a hummingbird that could be altered to match the description of our imaginary bird. In doing so, we also created a kind of natural-history museum one-sheet for both hummingbird and salamander for readers to enjoy. This also made me happy because it collects all of the great details Dr. Brown came up with, not all of which made it into the novel. While this image wasn’t inspiration for the novel, it is now potential inspiration for future fiction, which is often how my imagination works when “found objects” from one of my works makes it into the “real world.”

Another intersection of fact and fiction that influenced the novel was, quite simply, our new house on the edge of a ravine in Tallahassee, Florida. Built by a FAMU grad student in the 1970s, inspired by the structure of tobacco barns, especially the roof and upper windows, this place presents as treehouse, Escher creation, and ark. During thunderstorms, the lashings of rain seen from the upper windows make it seem as if you’re in a ship at sea, as does the little “deck” on the upper level. Down in the ravine, though we’re ten minutes from downtown, there’s a wealth of wildlife and we’ve done our part to rewild the yard by getting rid of invasives and putting in native plants. The design of the house, form-fitting the slope, and clearly conscious of flooding, erosion, and ecological concerns in its build, put me in mind of nature centers and environmental communities. The wildlife made me more intensely aware of the lives of hummingbirds, spending a season here before going back to South America. The house has been percolating in my imagination for some time and could be said to be a nexus for some of the benign environmental ideas in the novel.

Another structure that influenced the novel was the sustainable community of De Ceuvel—especially on Unitopia, the eco-commune/ education center created by a dead eco-activist in my novel. Our daughter Erin Kennedy is a senior consultant for the sustainability company Metabolic in Amsterdam and took us to De Ceuvel, in North Amsterdam. I was impressed by the way the “island” was built of recycled materials and how they were reclaiming a once- polluted place. The vibe is very much like this photo from the De Ceuvel site showing a party there. For my purposes, of course, dealing with dystopia, I had to make my Unitopia a more ambivalent place that might raise questions about how we pursue sustainability and whether people will listen. I hope our daughter doesn’t mind the moral ambiguity added, as her work in making cities like Charlotte, North Carolina, self-sustaining and carbon neutral is a source of great pride for us.

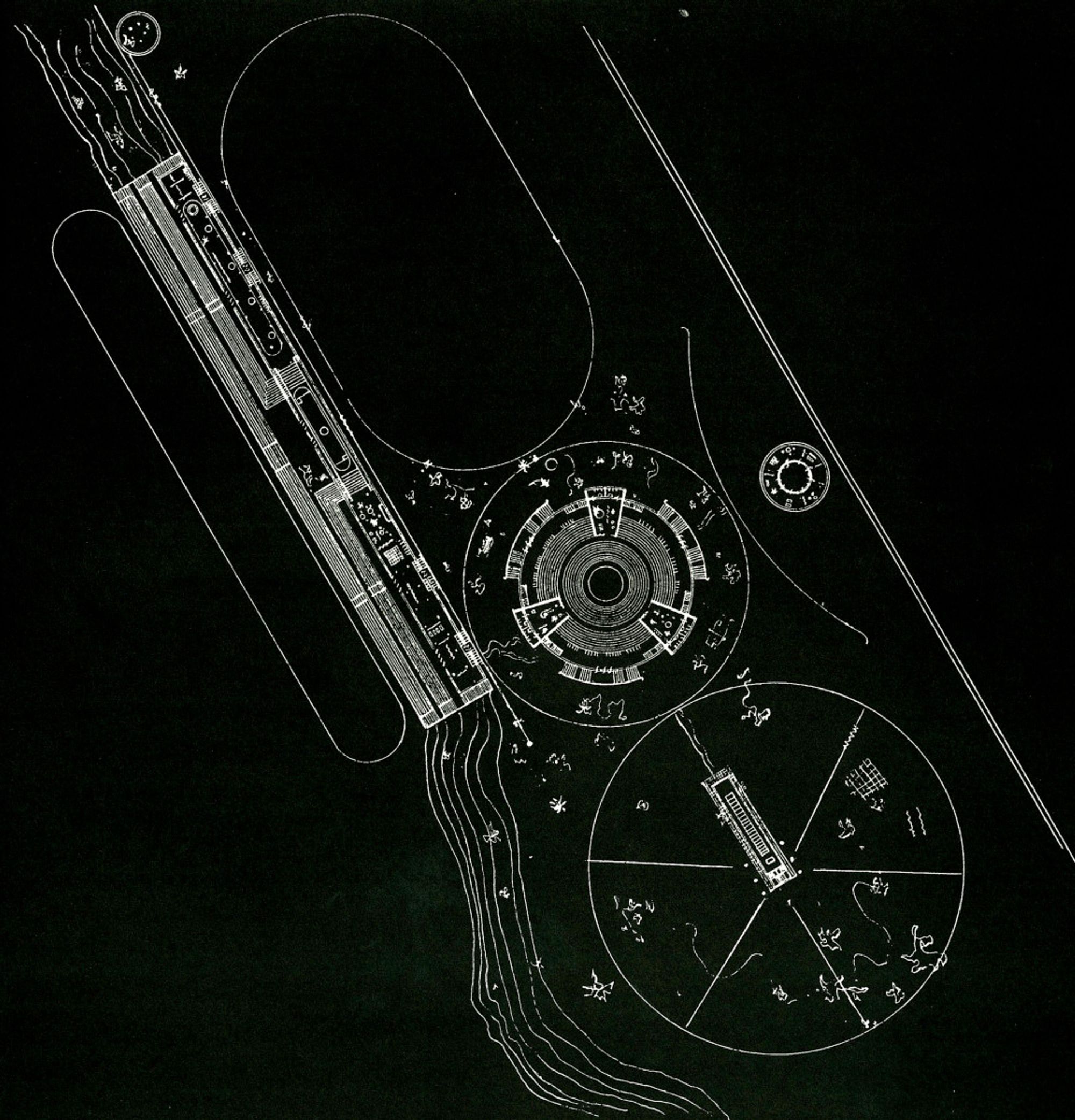

In envisioning Unitopia, which had thematic and practical reverberations throughout the entire novel, I needed an actual blueprint and one that was both utopian and slightly sinister. This “sinister” aspect is a kind of theme running through the novel, although mostly expressed through characters like Hellmouth. So I asked the artist, writer, and teacher Jer Thorp if he knew of any possible examples as he has expertise in related areas.The key was the style of the blueprint, and he suggested old Soviet-era utopian community blueprints. As soon as I saw the image above, I knew this would set the look-and-feel for Unitopia, with the white lines on a black backdrop and the suggestion not just of structure but of something alive. I was struck by how much this image looks in part like looking at microorganisms through a powerful microscope.

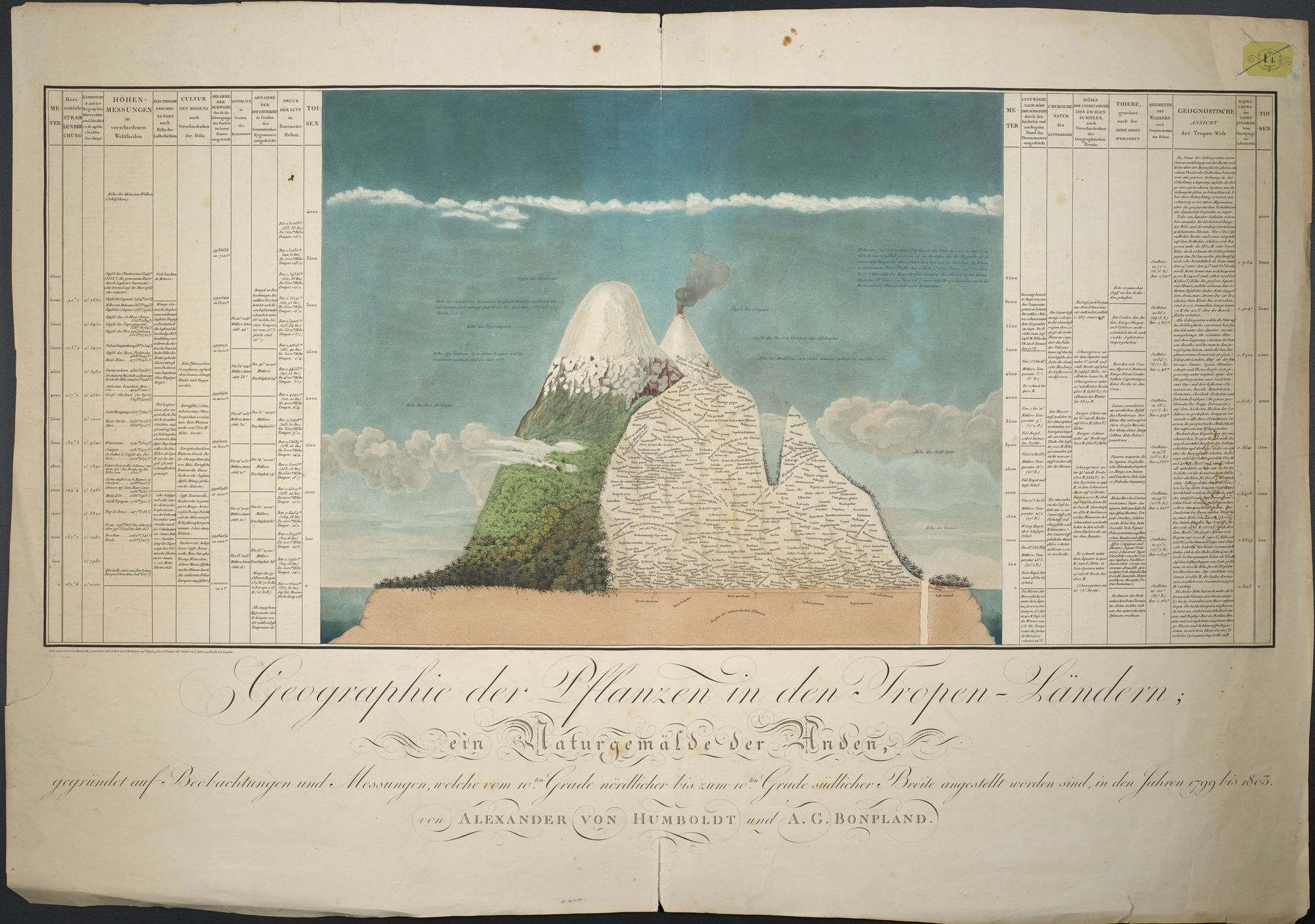

As connected to Silvina and to the idea of “Unitopia” was 1800s naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s idea of “total nature,” exemplified in several diagrams in his work that show the various ecosystems at different levels of mountainous areas of the Andes. I was drawn into Humboldt’s world through a recent book on the subject, but also because I liked the contradictions of his character: he was astonishingly progressive for his time, but was still a European documenting ecosystems subject to indigenous land management for thousands of years and thus an outsider; he was an ecologist but once electrocuted four thousand frogs for a single experiment. I saw the images in his books of the Andes as super-charged and suggestive of utopian ideas and practical ideas about earth-systems at the same time, of both a colonial and a post-colonial view. By including this in the context of Unitopia and other [redacted for spoilers] reasons, it felt like I was layering in a background of complexity that would lead the reader, if they wished to follow, on a journey well beyond the novel itself.

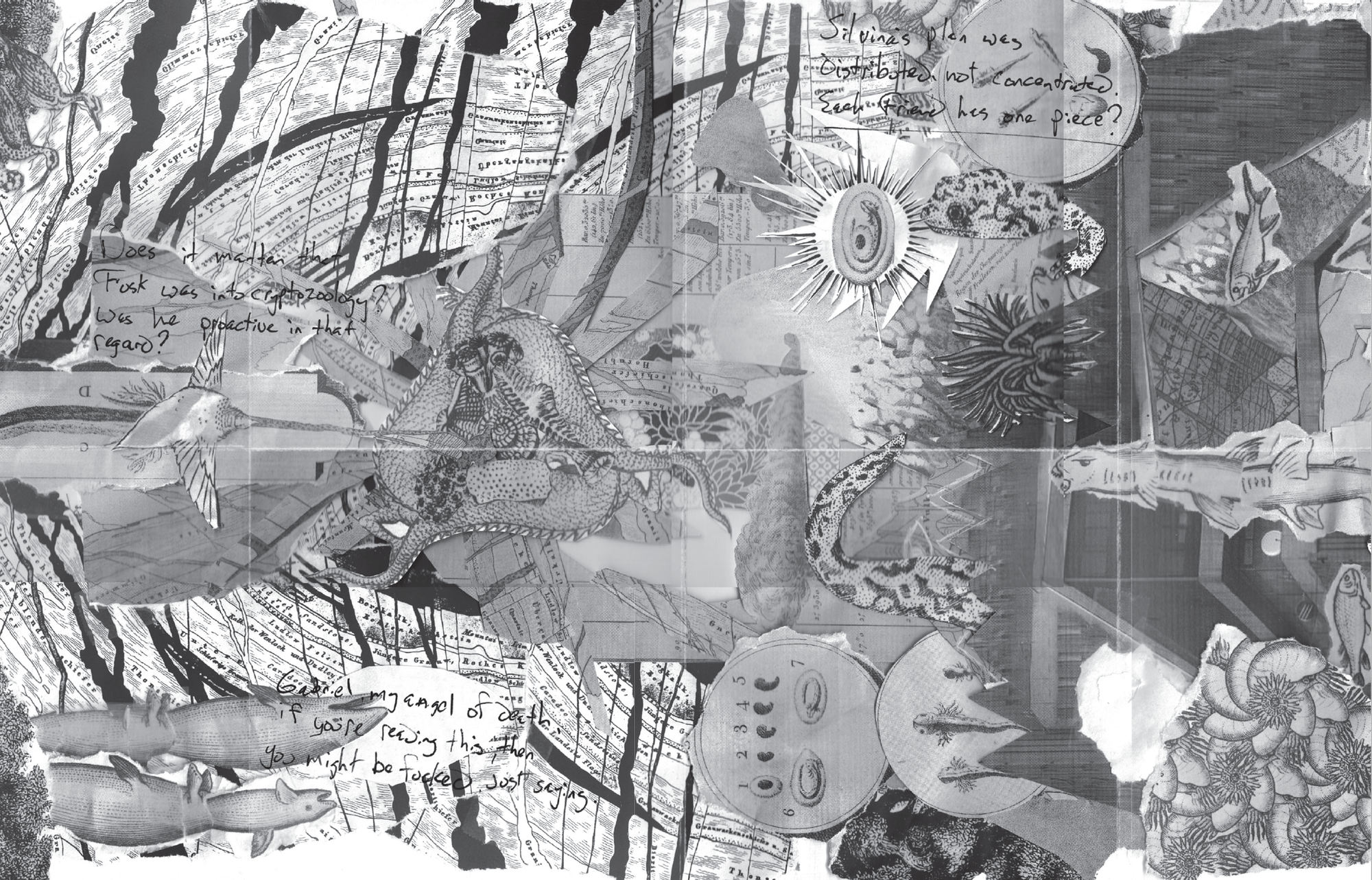

Then, you sometimes experience a frisson of the unexpected when you begin to bring the unreal into the real world. I’d been invested in testing out conspiracy theories and surveillance ideas in my book, but also in doing the research had begun to feel paranoid about who might be watching me as I did so. This kind of research—background for a novel—feels benign, but who knows, given the uncertainty of our times? I had wanted to conjure up Jane’s state of mind as she becomes more and more isolated. It might make me more susceptible to “mind viruses” from the internet for a time, I thought, but surely it wouldn’t result in anything more… which is why I was very concerned when I received the collage pictured, via snail mail, in a manila envelope with no return address. I recognized the elements of the collage, of course—they’re cut up bits of various images from Alexander von Humboldt’s books. But what was scrawled on the collage? And what to make of the note also inside the envelope, purported from the “Friends of Silvina,” an organization I had made up for the novel? The note read simply, “Hellmouth walks the Earth; here is your evidence.” …If I am honest, I am still trying to understand what line I’ve crossed without knowing…and if there is a way back.

Subscribe to Broadcast