13 Ways of Looking: Jenny Odell

Jess, The Unentitled Graces, 1978.

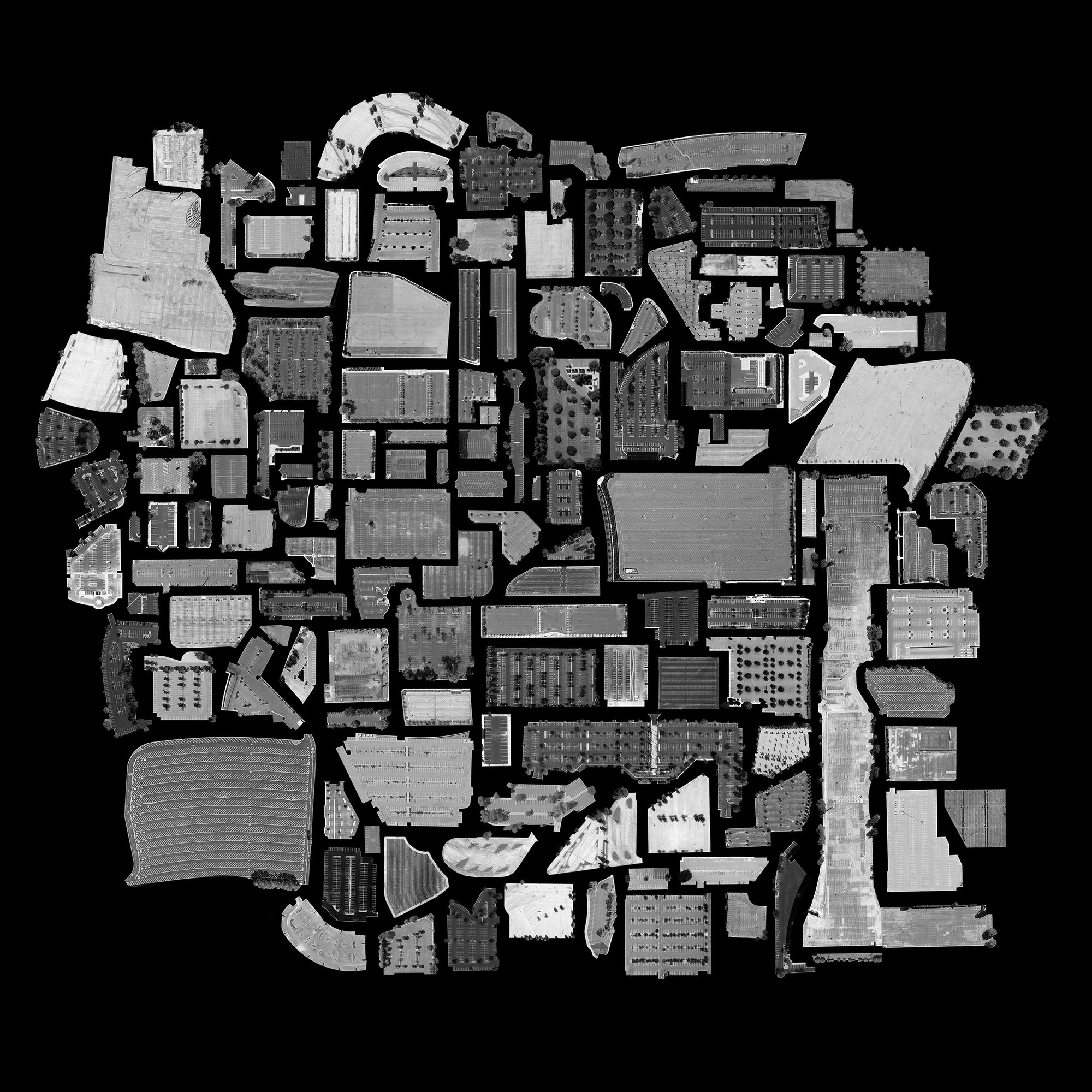

Courtesy of The Buffalo AKG Art Museum.One of the first artistic acts I remember is cutting things out. As a child, I would draw tiny people and cut them out with scissors, mostly for the purpose of tucking them inside the fold of a paper boat. Anyone familiar with my writing would probably be unsurprised by this love of collection, which showed up again in the fragmented, nonlinear essays I wrote in college and in the collages of cutouts from Google Earth I started making in grad school. I still remember the exhilaration I felt copy-pasting the first parking lot onto a blank Photoshop canvas for 144 Empty Parking Lots. Against the black backdrop, the excised shape was now free to enter into a conversation (about parking lots) with other parking lots.

Jenny Odell, 144 Empty Parking Lots, 2009.

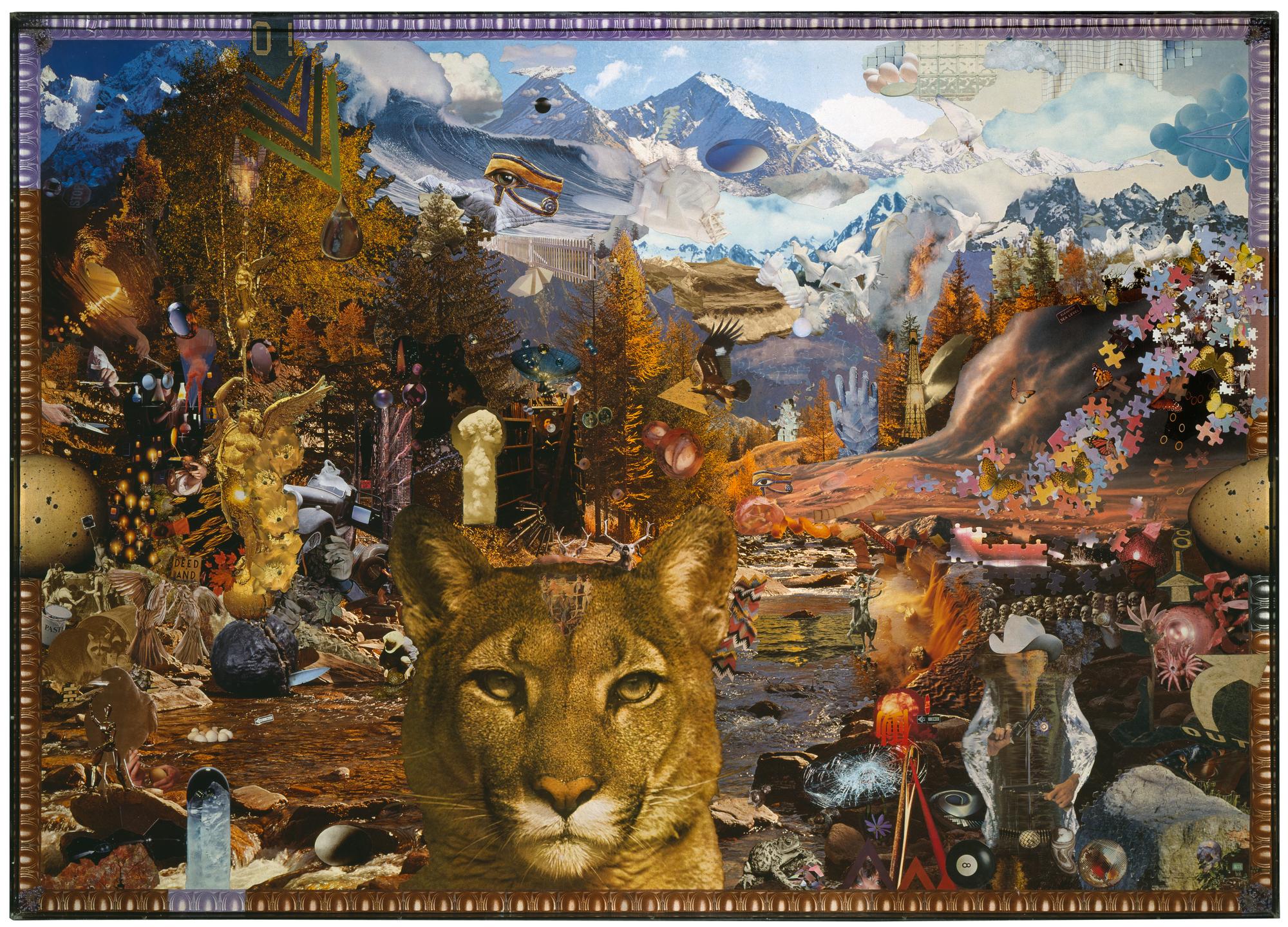

Courtesy of the artist.In 2017, not long before I would start writing the talk that became my book How to Do Nothing, I went to an exhibit on Surrealism at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center and saw a collage I would never forget. It was the five-foot-wide Midday Forfit: Feignting Spell II (Spring), made in 1972 by an artist who went by the mononym Jess. This piece felt like something I had been waiting to see, or had been trying to make, for years without success. It had to do with its sheer scale and coherence, marshaling what must have been thousands of pieces—from magazines, engravings, and puzzles—into one epic tapestry that moved me in an immediate way. I find it significant that even though I didn’t see the image again until years later (it’s almost nowhere online), the shape and effect of it remained in my mind: two figures in the color palette of a luxurious Turkish rug, swinging through a profusion of images that spill onto a wooden frame.

Jess (Jess Collins), Midday Forfit: Feignting Spell II, 1971. Paste-up: magazine pages, jigsaw-puzzle pieces, tapestry, lithographic mural, wood, and straight pin, 50 x 70 x 1 3/4 in. (127 x 177.8 x 4.4 cm). Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Restricted gift of MCA Collectors Group, Men’s Council, and Women’s Board; Kunstadter Bequest Fund in honor of Sigmund Kunstadter; and National Endowment for the Arts Purchase Grant, 1982.30, © Jess Collins Trust.

Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.Midday Forfit and the pieces that represent the other “seasons” of this series are from the middle of Jess’s career, itself somewhat surreal. Born Burgess Collins in 1923, Jess grew up in a conservative family in Southern California, studied chemistry, and was drafted to work on the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, Tennessee (where he also sent away for a copy of Finnegan’s Wake). In the years following the war, he took adult painting classes while working on plutonium production at the Hanford Atomic Energy Project in Washington state, now one of the most contaminated nuclear waste sites in the country. In 1949, Jess had a “nightmare premonition” that the world would destroy itself by 1975. He had also come to the conclusion that “the real truth—if there is such a thing—that you can learn from science is how little we know about reality,” and that “art seemed to address this more openly.” Jess redeployed himself to study painting at the San Francisco Art Institute (the same place where I would later cut up parking lots), dropped his last name, and married the poet Robert Duncan, with whom he’d fallen in love at a poetry reading at UC Berkeley.

Jess eventually moved on from making his own paintings to collaging, assembling found objects, and reworking old paintings that he found in thrift stores. More than one person has used Jess’s training as a chemist to inform a reading of his work as alchemical. (One reviewer in 1993 referred to him as “the supreme alchemist of the junk shop.”) Likewise, even before I knew any of this background, Jess’s work moved me because it so vividly exemplified what I love about collage: it’s not something from nothing, but something from something. The ingredients don’t just hang together in a new way; they truly become something else. Rather than a style of image or gesture, there is a style of use—you know a Jess collage (or “paste-up,” as he called them) when you see one. Duncan, who frequently collaborated with Jess, understood this alchemy better than anyone, writing: “Absolutely no part here is originally the artist’s. What he has achieved is totally his, but in every detail derivative.” This is perhaps most apparent in pieces that Jess made after he noticed that puzzle companies used the same cutout molds on different images, and subjected this knowledge to his own strange ends.

Jess, Deranged Stereopticon, 1974. Collage, 15.5x34.5 inches.

Courtesy of the Pasadena Museum of California Art.As someone equally drawn to the visual and the literary—and who experiences this as a conflict only when conventional boundaries are applied—I felt some deep sense of recognition when I found that the two books on Jess in the UC Berkeley library were in completely different sections: one in visual art, the other in poetry. In some of his earlier collages, recalling Dada, Jess used words alone; he also made his own books (a format he already saw as a “collage space”), which contain gleefully impure mixtures of images, quotes, and his own poetry. Many of his collages are covers for the books and journals of poet friends. Midday Forfit’s fragments may be wordless, but they still pun and rhyme. They frustrate any extractive approach to reading, the idea that content can be detached and refined from its context. In the paste-ups, each piece, each participant, each “word,” takes its meaning from other pieces. It is all selection and placement.

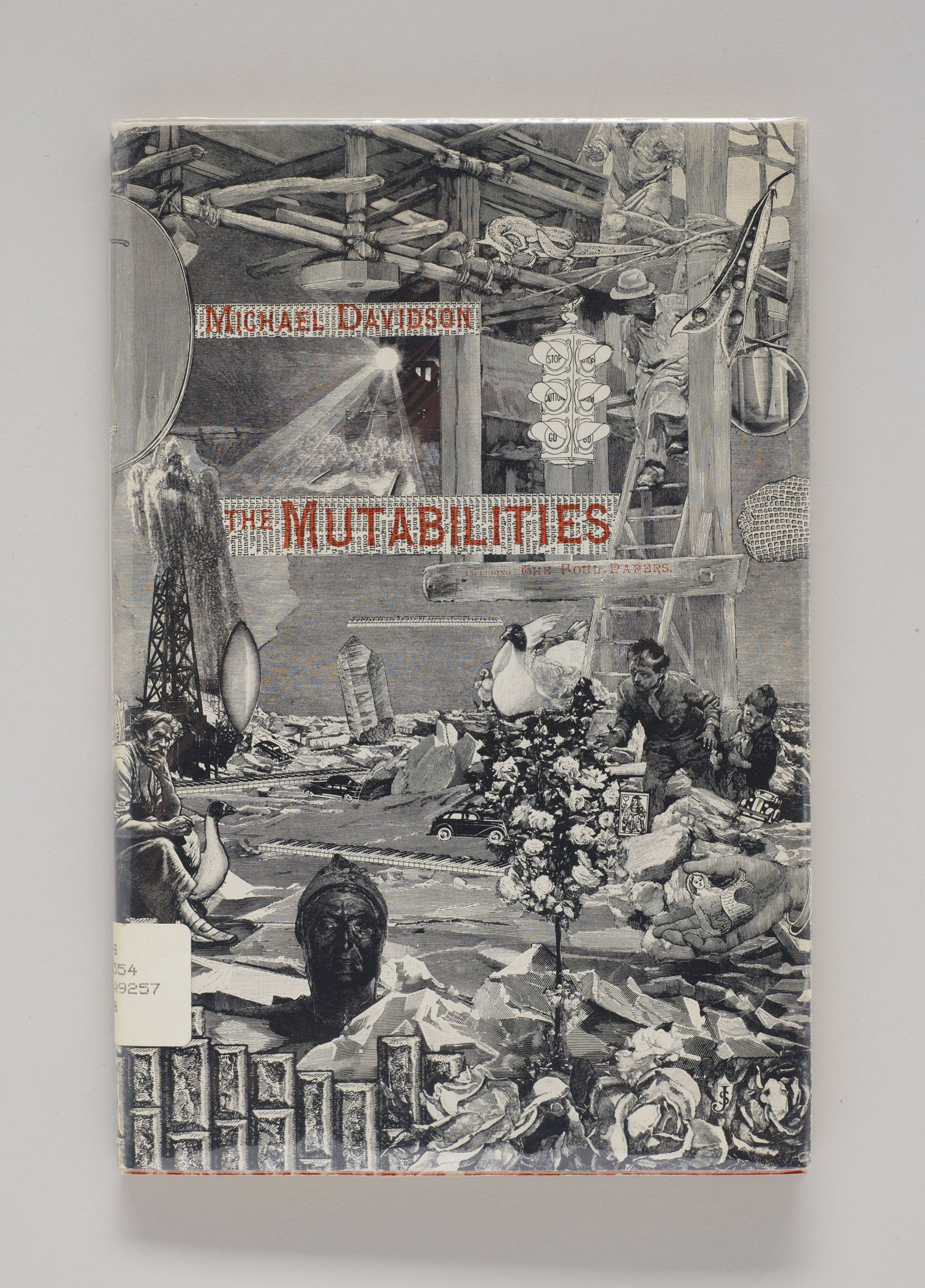

Jess, Mutabilities & the Foul Papers, 1976. Rosemary Furtak Collection, Walker Art Center Library.

Courtesy of the Walker Art Center Library.Not that I think anyone who looks at Jess’s more complex paste-ups would believe they were easy to make, but as someone who works according to a similar logic, I know the unseen periphery of time required of each composition. Some of Jess’s paste-ups took years to make, and his unfinished project Narkissos took decades. This would have included not just cutting and pasting, but noticing, first of all. In one interview, Jess told the curator Michael Auping that he salvaged most of his imagery from books, magazines, and postcards wasting away in thrift stores, but that images could also be salvaged from “a possible obscurity” if they had “spoken up out of the matrix of images that surround them.” Auping reports that Jess treated his scraps like family heirlooms and would sometimes hold on to a clipping for more than 20 years. While 90 percent of his filed-away scraps never made it into a piece, Jess would “ritualistically continue the process of searching, finding, and filing.”

Jess, Arkadia's Last Resort; or, Fête Champêtre Up Mnemosyne Creek, 1976. Magazine cutouts and puzzle pieces, 47 × 71 in. Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund, 1977.15 © The Jess Collins Trust.

Courtesy Dallas Museum of Art.

Jess, A Cryogenic Consideration or Sounding One Horne of the Dilemma (Winter), 1980. Collage, 48x72 inches.

Courtesy of Tibor de Nagy.Searching, finding, and filing—especially in seclusion, as Jess often worked—are what sense-making looks like to me. I grew up in a time of grotesquely proliferating information, easier than ever to access and with a seemingly total lack of structuring narrative. For me, collection and arrangement were a response, a necessary adaptation: you could give up and live in a senseless world, or you could set about building sense from whatever scraps you could find. But this arrangement could be a pleasure in and of itself, full of devotion to each little piece and to the kind of complexity that needs only finding, not making. In a short text collaged into an announcement for Jess’s 1959 show at Dilexi Gallery, Duncan calls Jess’s art “not impression, not expression, but an involvement in what is.” It is this assumption that meaning is to be found among what [already] is that I relate to most in Jess’s work.

Jess, A Western Prospect of Egg and Dart, 1988. Printed papers and jigsaw puzzle parts mounted on board, 56 1/4 x 79 3/4 in. (142.8 x 202.6 cm). Gift of the Marion L. Ring Estate, by Exchange, 1989. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

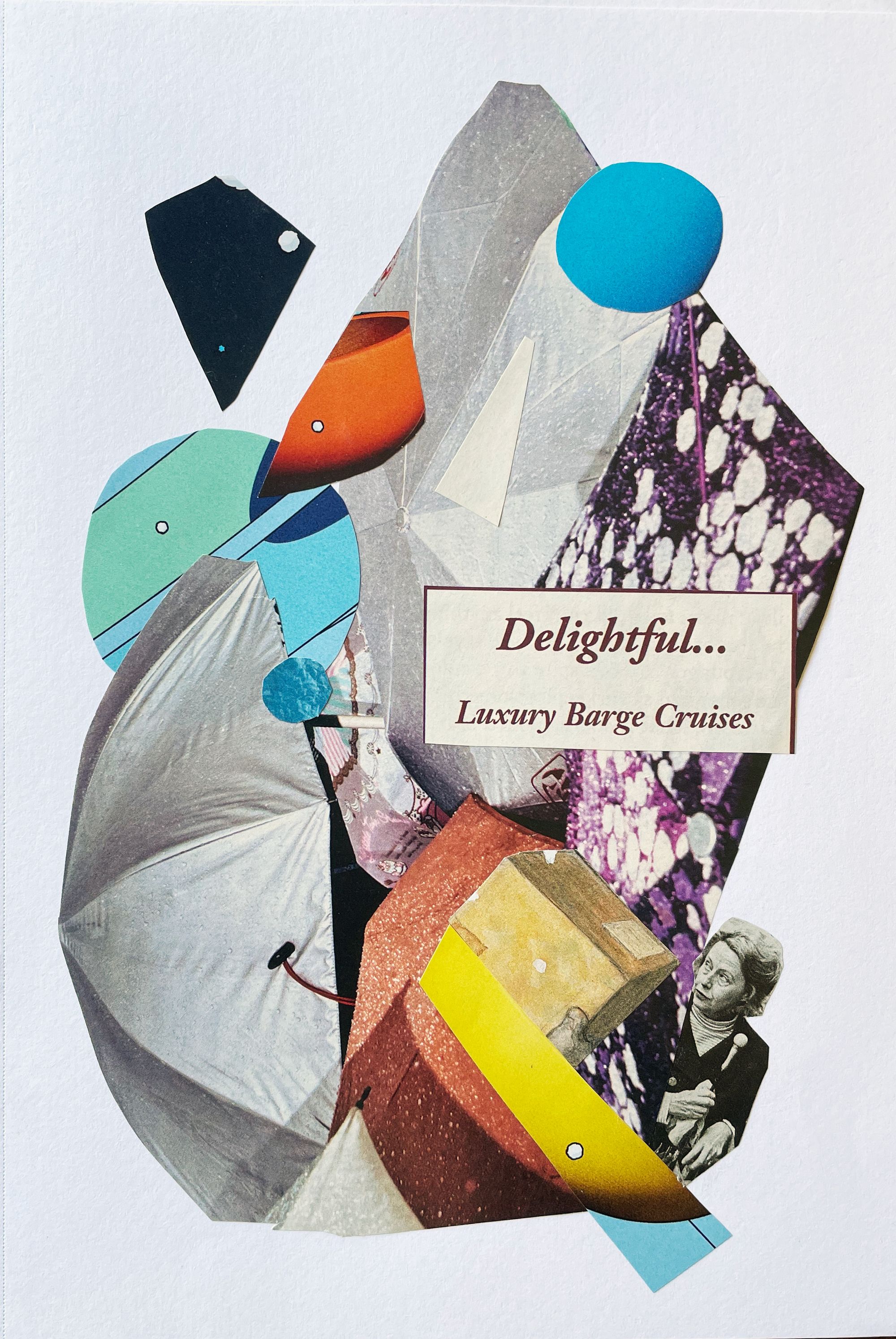

Photo by Lee Stasworth.In the pandemic years, when I was writing Saving Time, I sometimes returned to the humble art of making collages from whatever magazines were lying around, inevitably with Midday Forfit in the back of my mind. I did this not as an art practice, but as a writing practice. Collage reminded me that even in nonfiction, there are so many more ways for things to be related than in a linear, causal manner. Likewise, those little collages were how I remembered that my book was not so much a traditional argument as an arrangement, what Jess might’ve called “a matrix for the imagination.” In How to Do Nothing, I mention the closing exhibition for my residency at Recology SF (the city dump), where I had made something like a collage: an archive of two hundred salvaged objects, monomaniacally researched and presented with tags you could scan in order to learn their life stories. “I don’t get it,” a woman had said to me. “Did you actually make something, or did you just put things on shelves?” The truth was that, with utmost care over months of late nights in the studio, I had just put these things on shelves. I’d compiled these histories, put them there, for her—to help her see them anew.

Jenny Odell, Untitled, 2020.

Courtesy of the artist.

Maybe it’s just because I don’t like being told what things mean, but to me, the most generous thing an artist can do—regardless of medium—is to create a distinctive space, a kind of ego-less garden in which a visitor finds her own way. Auping, the curator, once asked Jess if there was some specific personal history behind Narkissos, a drawing-turned-collage-turned-painting that he started in 1954 and was still working on in 1989, when the Loma Prieta earthquake struck and he had to reorganize all of his files. Jess responded, “There are many stories. I really would not want to tell you what I see and that often changes anyway—because that would limit your seeing.” The work was, for him, “not a narrative, but more a dialogue of presences.” Likewise, for the curator Ingrid Schaffner, the paste-ups offer “no traditional ground to stand on or conventional narrative paths to follow,” calling upon the viewer to perform “an open mode of exploration across a deliberately slippery terrain.” Slippery, but not traction-less. The explorer is not lost. Schaffner is describing the kind of richness and density that offers trust—and, in my opinion, respect.

This means that each viewer’s experience, provided they accept the invitation, is bound to be especially personal. In a review of that 1989 Dilexi show, toward the end of a generous contextualization of Jess’s work and a defense of collage against claims of postmodern cynicism, Rebecca Solnit (an art critic at the time) included a surprisingly touching detail when describing one of the paste-ups. She wrote, “I liked best the tiny lion bearing a cupid as he bounds over a lotus.” I too have little favorites: the woman’s arm turning into a package of saltines in The Unentitled Graces; the bathing man sipping tea spliced into the creek in Arkadia's Last Resort; Or Fête Champêtre Up Mnemosyne Creek [Autumn]; Barbara Streisand’s eye (the only visible remaining remnant of the poster he used) peeking through puzzle pieces in Whatever!; the inviting wooden chair amidst red and white dahlias in On the Way To Rose Mountain, suggesting a place to sit and admire the tangled garden of imagery.

Jess, The Unentitled Graces, 1978. Collage, 39x59 inches.

Courtesy of The Buffalo AKG Art Museum.The day I spent hunched over the two Jess books in the Berkeley library (before they would be re-shelved to their separate homes in art and poetry), I emerged from the building only to find myself in a different collage. The paved walkway was straight, but the campus was made out of fractal paths of noticing, each with its own surprising details: the perfectly constructed beehive outside the library, the man in a skeleton costume posing for a photo in front of the science building, the peregrine falcon shrieking overhead while he did. Every oak leaf, edges backlit by the afternoon sun; every tired shoe crossing Oxford Street; every menu item outside the Persian restaurant; every metal pipe along the ceiling of the BART station; every plastic curve of the AC Transit bus; every scratch on the window through which I saw every stucco wall and peeling billboard. In the visual frame left to me by Jess, the meaning was to be found not in the things themselves, but in the dialogue of their presences. It’s a language I’m still learning how to see and write in. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast