13 Ways of Looking: Kate Zambreno

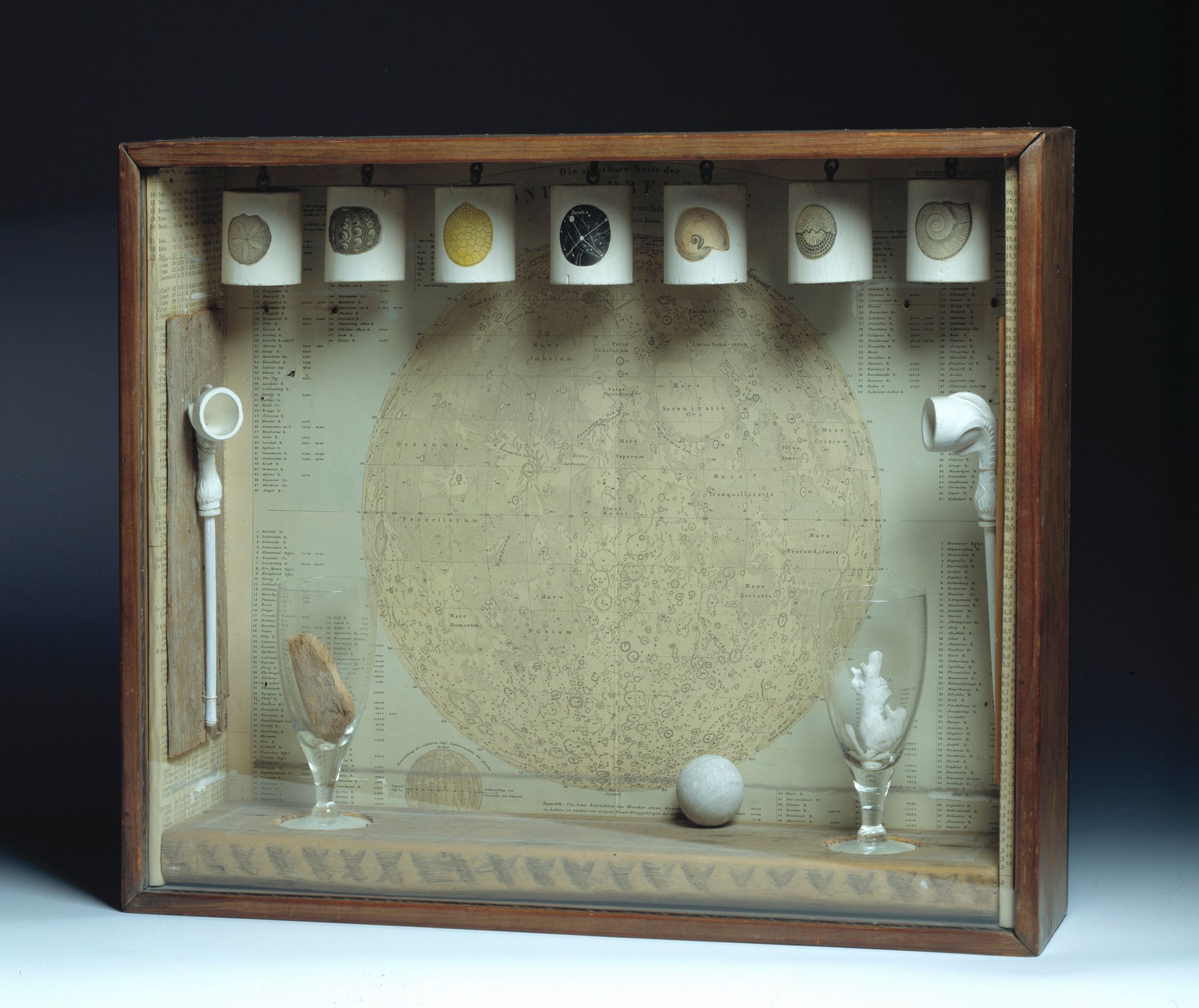

One of my first mystical encounters with art was returning to visit the Joseph Cornell rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago, when I came of age in that city. Often I would take the train just to see Cornell’s boxes, which at the time were in a darkened series of rooms, a nesting atmosphere like the artist’s cellar. In the backroom, you could push a button for the blue light to go on, in one of the owl boxes. Everything felt so bright and glassy and different once they were moved to the new Modern Wing years later. Thinking of Cornell’s poetics of organization helped me think about form as I became a writer—the page as a room or a box, inhabited by objects—and allowed me to think about tone, which had something to do with light. How could a passage of text somehow glow with its inner memory? How could writing be somehow about the mystery and magic of collection?

Often, the letters and diaries of Joseph Cornell have illuminated my work—they appear in my book Drifts, which is about thinking through writing as correspondence, and the (small) life of the interior. And I return to Cornell as a patron saint of The Light Room, a project that attempts to document the beauty and exhaustion of two years spent mostly indoors with small children, with excursions to parks and other public spaces. The book takes the form of a series of meditations whose energy and shape are informed by Cornell’s own ways of looking, his own life of thinking and artmaking. Even the idea of a series, or working within variations, is inspired by Cornell—one of the main movements of the book, “Medici Slot Machines,” thinks through childhood toys and collectibles; it’s named after his assemblages that herald children as nobility, as well as his soap bubble sets, that also gesture to the beauty and ephemera of childhood. But the inspiration of Cornell, and his idea of “illuminations”—observations of the outside world, often gleaned from daily walks—is everywhere throughout The Light Room’s first movement, “Lightboxes.” It’s set in a domestic interior—sometimes cozy, other times claustrophobic—but marked by muddy and solitary walks in the park, amidst brightness and shadow. Perhaps the atmosphere I was looking for in this winter notebook was the feeling of looking through a series of lighted windows.

Whenever I write a book, I search for ways to categorize its forms—for The Light Room I turned to forms of light, notebook pieces that felt to me like translucencies. A friend who read it suggested that the book reads like a calendar, which I really liked. Visual calendars were an inspiration for The Light Room, as well as what I am actively looking at in its pages. The paintings of Etel Adnan, who died when I was writing the book, and whose poetics linger throughout, were key, as was her belief in finding energy in the seasons. In the book, I write about the first time I see art again in the outside world during the pandemic—it’s the Etel Adnan show at Galerie Lelong, in the winter of 2020. I recall holding the hand of my oldest, while wearing my newborn, regarding both Adnan’s small vertical planet paintings—the simple beautifully colored circles that look like calendars for children—as well as the quartet of her seasons, the blots of paint around the black lines of trees.

Etel Adnan’s paintings are so wonderful to look at with children. The title of the show, “Seasons,” is a quote from Adnan’s 2017 book-length poem Surge, which I love and teach—“Why do seasons regularly follow their appointed time, deny their kind of energy to us?” I think in The Light Room, beginning with the winter notebook, I am asking whether a narrative can emerge out of the seasons.

For so long I have been trying to think about how to write the poetry of Yuji Agematsu, his gleanings from his daily walks around New York City. He collects bits of detritus off the streets—pieces of gum, feathers, wisps of hair, candy wrappers, assemblages—which he gathers together in the cellophane wrappers of daily cigarette packs—what he calls “zips”—which are then arranged in calendar-like monthly rows in Plexiglas cases, miniature ecosystems that continue to decay over time. Throughout The Light Room, I think about Agematsu’s “zips” when watching the accumulation of things in my apartment, the charge of the juxtaposition of things, both inside and outside, as Jane Bennett writes in Vital Matter. So much of The Light Room, and my thinking through domestic time, comes from meditating on artists who made conceptual work out of time, out of the ritual of gathering and organizing, which reminds me of the play of children.

I began to think of this as a box practice—mine, Cornell’s, Agematsu’s. David Wojnarowicz’s Magic Box, the collection he kept under his bed of 59 small objects, stored in a wooden citrus pine box. I first saw it in a show curated by Julie Ault at Galerie Bucholz, on the Upper East Side, in 2016. In The Light Room I think about how Joseph Cornell and David Wojnarowicz collected what children often collect, or how the Magic Box was possibly an actual collection kept from childhood, or recollected, like Cornell, after being an adult.

What did it mean, I wondered, that Wojnarowicz’s Magic Box contained objects like my five-year-old child’s own box practice: the toy horses, the plastic bugs, the beaded necklaces, the foreign coins, the stones, glass and crystals arrange by color, sometimes housed in tiny embroidered purses and even tinier boxes; items that took on a magical, almost totemic, function in Wojnarowicz’s videos and paintings. There is a magic, also, to the list of objects, as recorded in the finding aid at the Fales Library at NYU, to the actual fragments on the page, that I repeat in The Light Room. A list taking on its own thingliness.

Much like Joseph Cornell’s boxes, The Light Room is also enthralled by the weirdness of the natural history diorama, its play of reality and unreality. The second movement in the book, “The Hall of Ocean Life,” thinks through ecological grief and planetary despair, finding solace in David Wojnarowicz’s grief journal, which reveals a deep love of the natural world, the land of forest and swamps, of reptiles and dogs, clouds and trees, filtered through the black and white photographs of Wojnarowicz’s mourned love and mentor, Peter Hujar. I document trying to write about the grief journal, and also Wojnarowicz’s unfinished film of the beluga whales at the Coney Island Aquarium, which he and Hujar would visit as Hujar was dying, a spectacle they found beautiful and devastating. I write through visiting the Natural History Museum and the polar bear diorama I knew first from the photograph of Hiroshi Sugimoto, which most likely prefigures Wojnarowicz’s own famous photograph of a buffalo diorama in Washington DC.

While walking through the Hall of Ocean Life at the Natural History Museum, I also think about Etel Adnan’s love of the horizon in her paintings, and Sugimoto’s own horizon photographs, and how Wojnarowicz wrote about clouds, the play of darkness of light, the utter abyss.

Often in The Light Room I’m searching for artists who document the ongoingness of domestic time. “The Hall of Ocean Life” is layered over several winters, going from early pregnancy before the pandemic to breastfeeding a growing baby. In this movement I think about that Peter Hujar photograph of the baby breastfeeding against the planet of his mother’s breast, the utter absorption of time passing. Mierle Laderman Ukeles considered breastfeeding part of maintenance art: the often invisible, often arduous domestic labor documented in her manifesto as well as in artworks like her piece “Dressing to Go Out/Undressing to Go In.” I reference this work in “Lightboxes”: the artist putting on and off the outside winter coats and boots of her two children, with white dust cloth and a chain as a three-dimensional object, care work as endless repetition.

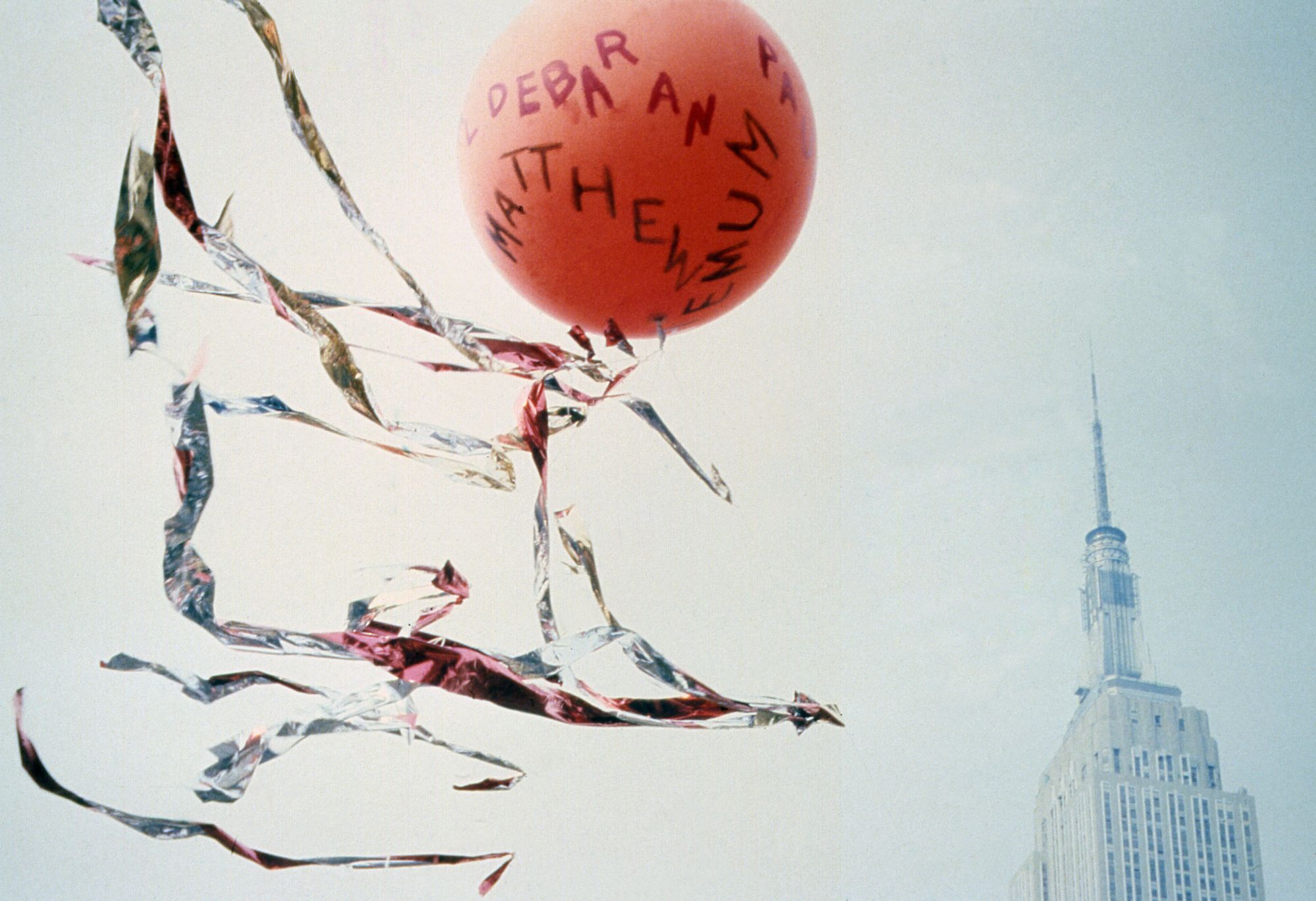

The last movement of the book, “Translucencies,” is a notebook of seasons, holidays, and exhaustions. It’s dedicated to the sisters Rosemary and Bernadette Mayer, inspired by their ways of looking, and their conceptual projects documenting time and the ephemeral. When looking at foil birthday balloons stranded in bare park trees, or watching children build melting snowmen, I think of Rosemary Mayer’s outdoor installations, which she called temporary monuments, her balloons or snowpeople, transient festivities.

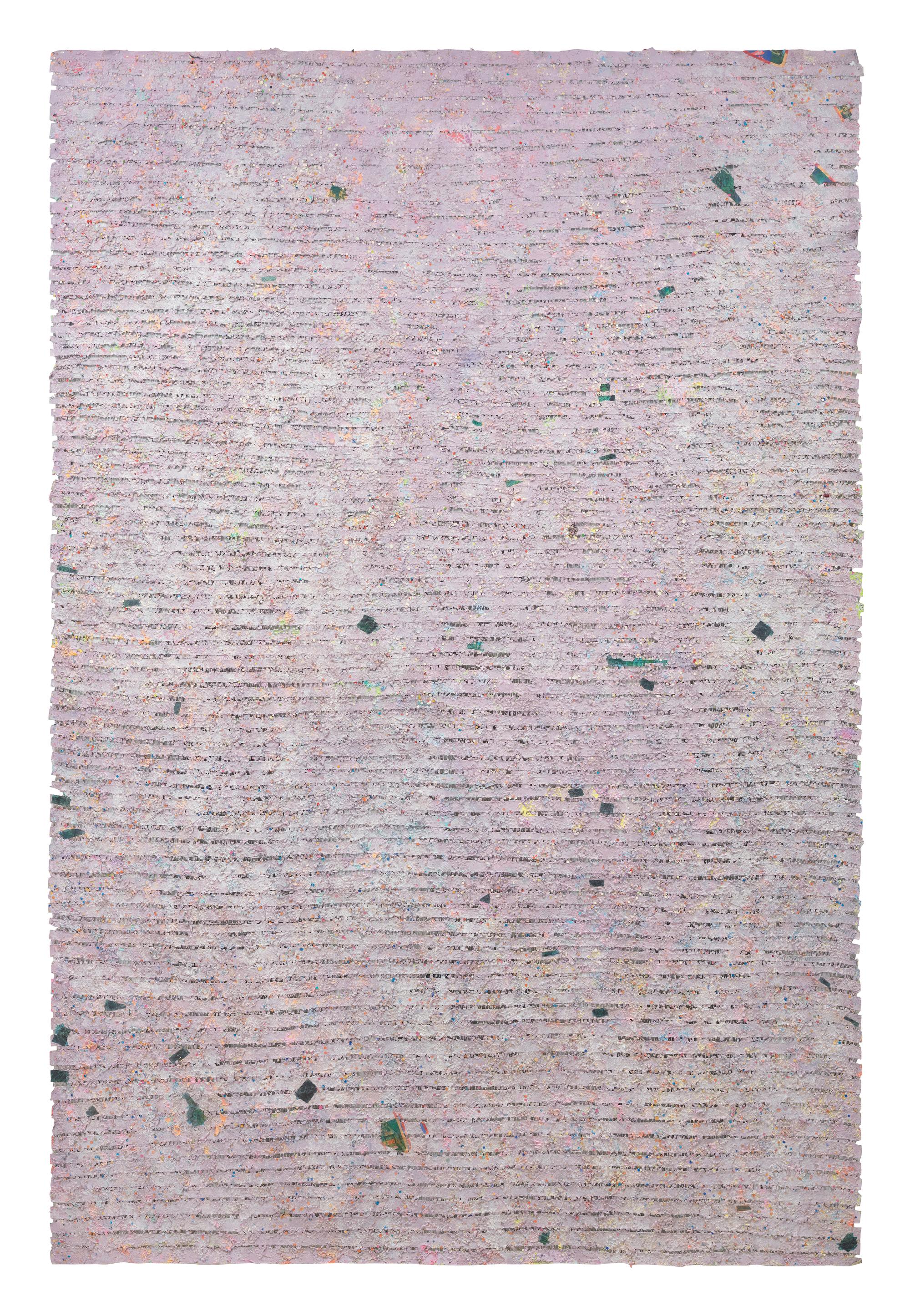

Throughout the reoccurring winters, which appear at the beginning and end of the book, I thought of the texture of Howardena Pindell’s glittery paintings, made out of hole-punched paper and foam, which have the feeling and memory of New York City blizzards.

All of these artists and artworks I actually write about in the book. For me writing is about looking and thinking and feeling.

One artist who was important to the book but, I realize, is not referenced at all is the artist Ruth Asawa. I remember on a visit to MoMA spending time with the repetition of her laundry stamp in a tight irregular grid on a sheet of fabric—neither painting nor weaving but suggesting both. Asawa made the piece in her student days when she worked managing the laundry facility of Black Mountain College. The morning I was set to be induced with my second child, in the first August of the pandemic, I remember staring at a photo of Ruth Asawa making one of her wire sculptures, surrounded by her children. I found comfort in realizing how close to children and childhood were so many artists that I loved, and that the space of the domestic could feel like abundance. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast