13 Ways of Looking: Rachel E. Gross and Armando Veve

Vagina Obscura started out as a dive into the innermost reaches of the human body, one that I hoped would bathe readers in the wonders of reproductive biology. Along the way, I would recount the wacky history of how scientists of yore envisioned these elusive organs (uteruses as inside-out penises! Ovary juice as the elixir of life!), as well as all the ways modern explorers are reimagining them today (uteruses as hotbeds of regeneration! Ovaries as rechargeable batteries!). By journey’s end, I hoped to impart a sense of how much the uterus, ovaries and vagina do to support body-wide health beyond just baby-making: for instance, by participating in immune function and pumping out hormones that support virtually every bodily system, from blood to brain.

In doing research, and in thinking about the kind of illustrations that would reflect these aims, I pored through old anatomical textbooks and archives of long-dead scientists. A few themes stood out: over and over, the female body was described as an inferior, shoddily constructed version of the standard male body. Female genitals were drawn as unfinished or inverted male ones, and generally considered interesting primarily for their role in reproduction. In other words, I had no shortage of examples of the kind of imagery I hoped to move beyond. The challenge in creating imagery for the book became clear: to imagine a landscape that didn’t yet exist.

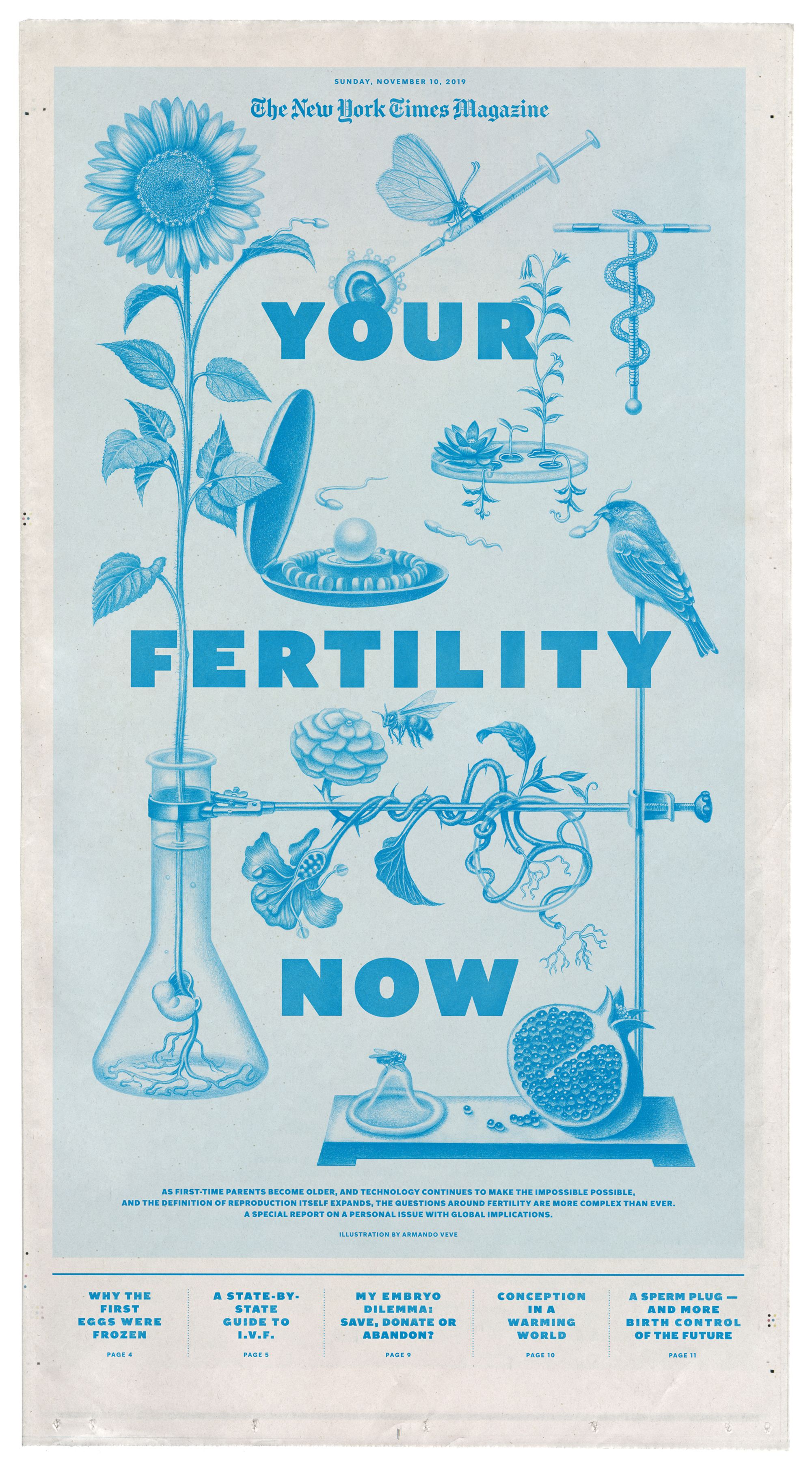

I first became aware of Armando’s work in 2019, when I wrote a piece for a special section of the Times Magazine on the future of fertility. I was thrilled to see the piece, which was called “Why Women on the Pill Still ‘Need’ to Have Their Periods,” accompanied by a finely sketched image of a a pearly egg cell, sitting atop a Pill container and being hungrily circled by two eel-like sperm. The artist was Armando. He had illustrated this entire section with images that took the masculinized visual language of scientific sketches, test tubes, and bodily organs, and undercut them with surprising, whimsical, and often delightful flourishes.

Armando’s drawings echoed how I was starting to imagine the female body: as a world etched with care and precision, yet also bursting with unexpected details, tendrils of possibility that had yet to be described.

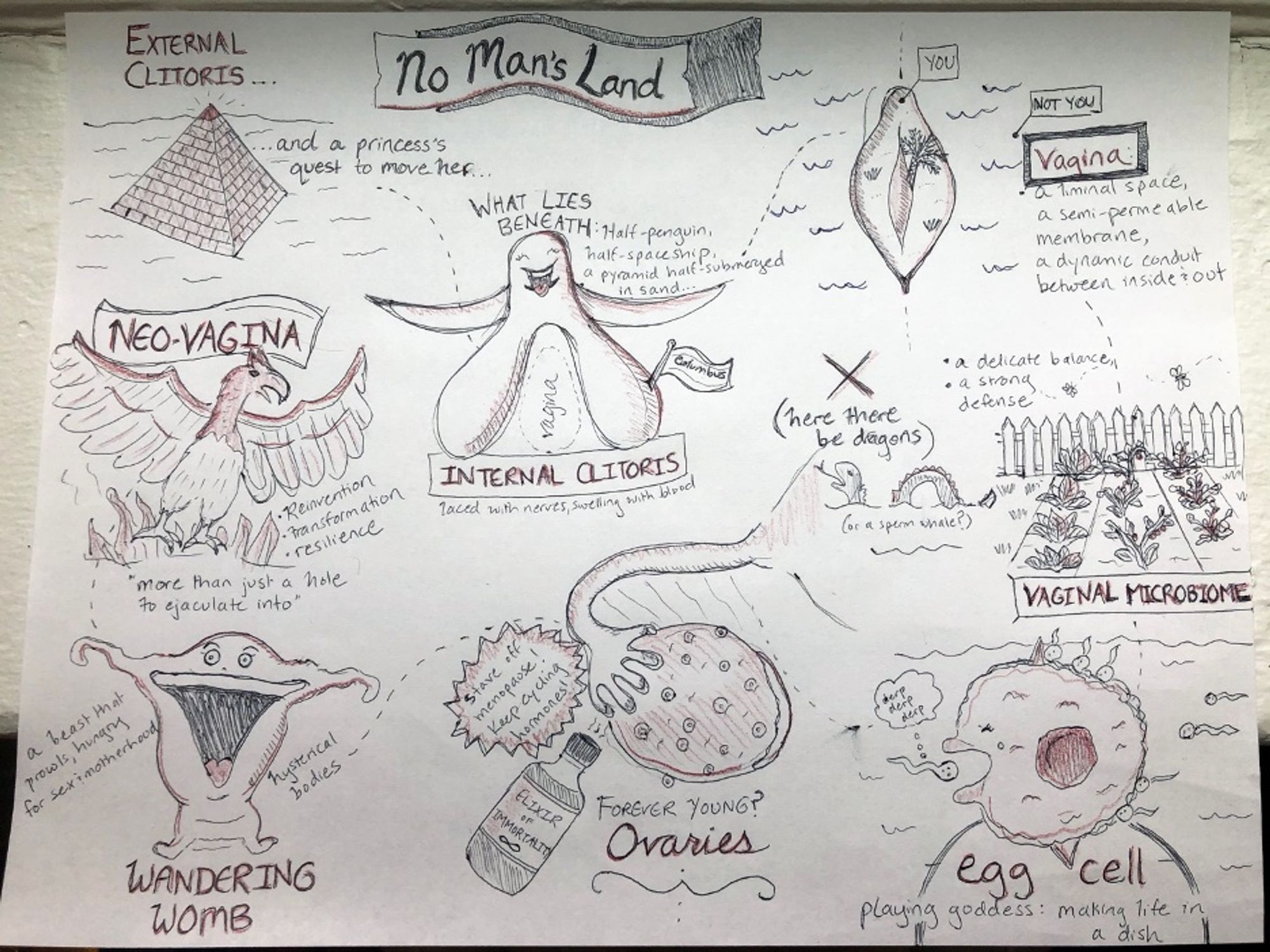

I reached out to him and, in our first conversation, he asked me to sketch a “thought map” of my book. Kindly declining to make fun of my artistic skills, Armando was able to distill from my crude sketch some big themes: power, pleasure, resilience, and decolonization. He also got a sense of the playfulness and surprise we were both bringing to the project, and to the visual world we would co-create—a world that zoomed in on the organs of the female (and nonbinary) body as uniquely active, dynamic, and regenerative.

When Rachel shared how she was going to structure her book, a landscape took shape in my mind. Each pillar of thought became an erected or excavated site to discover in her “No Man’s Land.” The language of maps, infused with wonder and discovery—and also rooted in a darker history of colonialism—gave me a fertile starting point for understanding Rachel’s project, a quest to reclaim a history that was once taken without consent.

At first, though, I admit I was hesitant to take part. I thought the images for the book should be made by a female illustrator who would be able to connect with the subject matter from a place of shared, personal experience. What right did I have, as a queer, cis-gender male, to create images meant to reclaim the history of a body that was not my own?

But it was clear from an early draft Rachel shared with me that she was not just writing a book about the female body solely for a female audience. She was writing a history of the female body as a window into a greater understanding of all bodies. From our first Zoom call, I felt a kinship with her. Working on Vagina Obscura became an opportunity for me to move outside my comfort zone and engage in a conversation that transcended gender.

We began to exchange ideas and visual inspirations—both antiquated images and newer ones, like this beaver holding a vibrator from a WIRED article Rachel wrote years ago. It became apparent that our collaboration could be special.

If Vagina Obscura has a central character, it may be the clitoris. No body part has been argued over so vehemently, disparaged so thoroughly, or “discovered” so many times by a parade of male anatomists. Andreas Vesalius, the so-called “father of anatomy,” once mocked his rivals for claiming to have uncovered “this new and useless part.” And yet, time and time again, the clitoris has managed to emerge from this history of erasure, reinventing itself as control center and feminist icon.

A key inspiration for how we sought to re-imagine this organ came from Brooklyn artist Sophia Wallace. Long before Vagina Obscura was a twinkle in my eye, Sophia had spent years learning the shape and contours of the full clitoris, creating 3D sculptures to represent its full form, and inspiring a new iconography of the clitoris she calls “Cliteracy.” Just as towers and obelisks subconsciously evoke the male phallus, her sleek, curving sculptures are part of a burgeoning movement to create equally recognizable shapes that reference the power and potential of the female genitals.

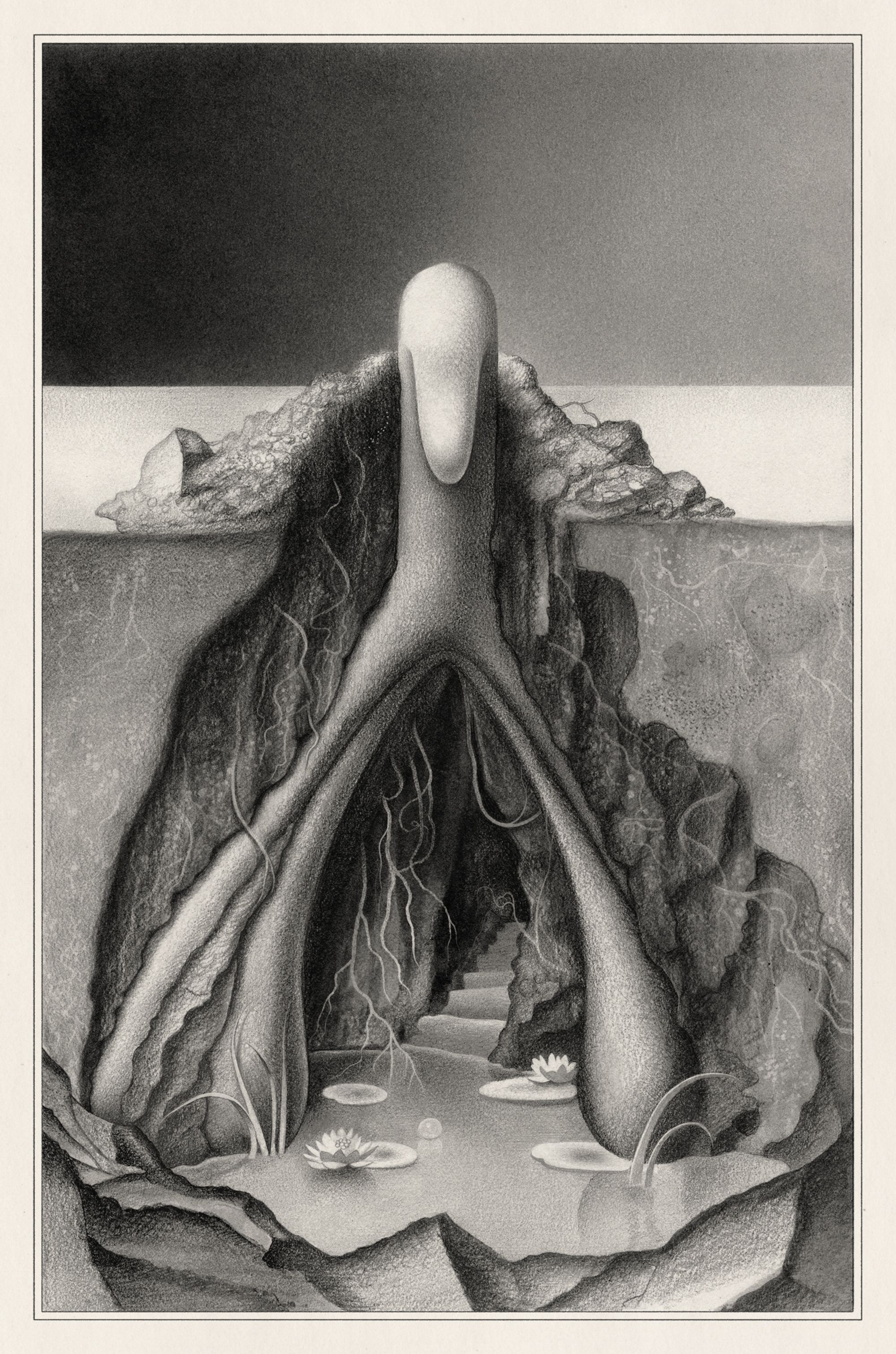

The clitoris was one of the first “sites” that solidified in the process of making this book. When I’m conceptualizing a new image, I usually begin with loose sketches, lists of phrases and words I collect in my research, and conversations with collaborators. When I analyze my scrawlings, I am looking for new bridges and pathways between disparate ideas. The “aha moment” occurs when I find an overlap between two divergent thoughts. I recall one of these moments in a first conversation with Rachel over Zoom. She held up a 3D-printed clitoris, turned it to its side and pointed to a protrusion at the top stating, “This is the beak.”

The winged structure immediately evoked fantastical images of mythological flying creatures and the sleek fluidity of a Zaha Hadid skyscraper. In my final graphite drawing, the clitoris is at the center of an excavated site. Its large bulbous “roots,” otherwise known as the bulbs—which I learned had historically often been omitted from scientific illustrations or considered to belong to the vagina—are visible and pulsing beneath the surface. On the cover of the book we see the same structure silhouetted in the distance, fully uprooted and now liberated as she flies over the landscape. We later dubbed it the “clitoridactyl.”

While it may seem counterintuitive, the vagina was more of a challenge to visualize than the clitoris. I was particularly keen to avoid the clichéd trope of using cut fruit or flowers as a euphemism. At the same time, Armando and I talked about wanting to move away from imagery that painted this powerful, muscular organ as a negative space, or a lack. For centuries, male anatomists had seen the vagina as merely a cave to be inhabited, or—as the Latin name suggests—a sheath for a sword. I knew we could do better.

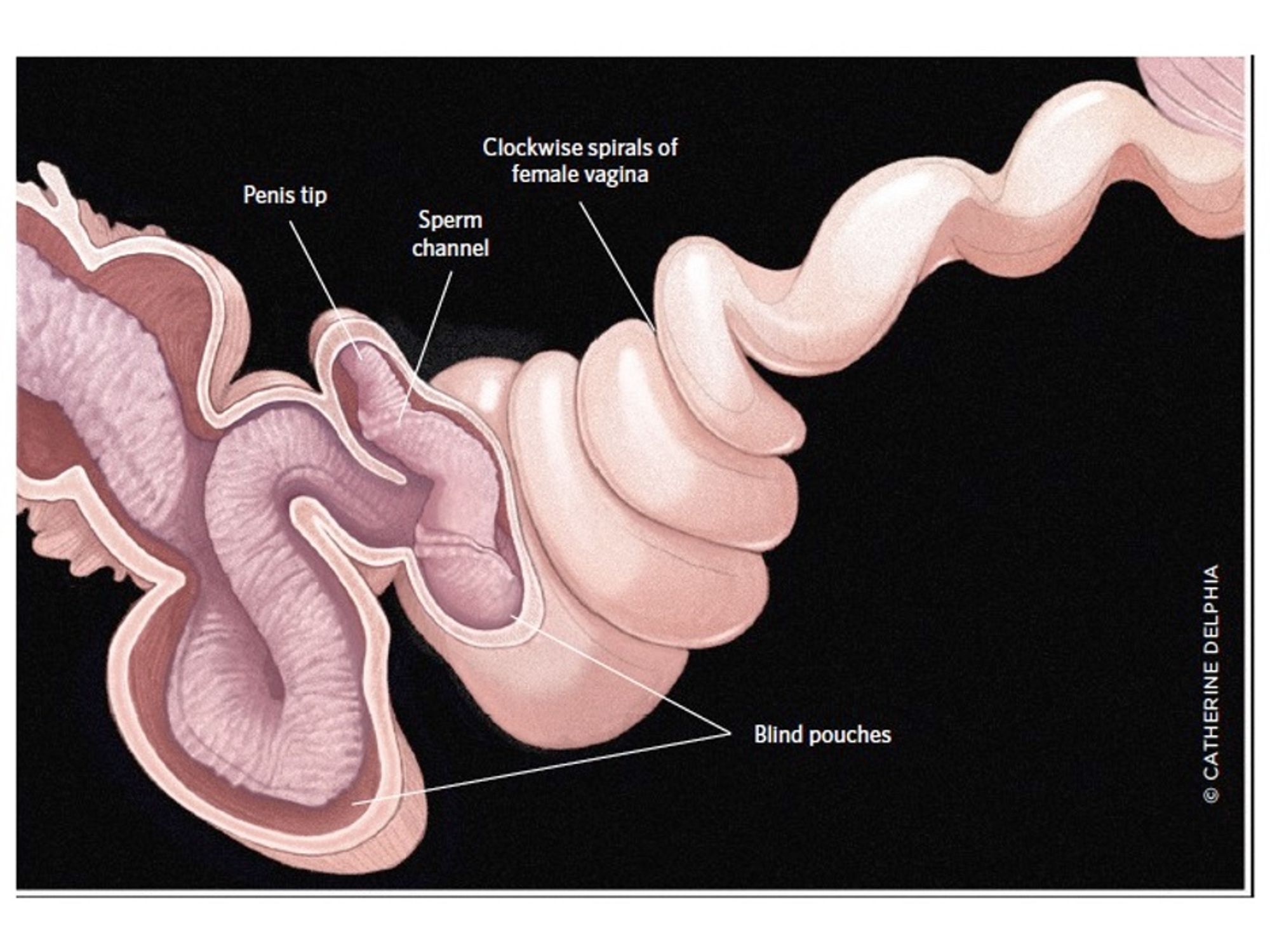

This illustration, which represents research on duck vaginas by evolutionary biologist Patty Brennan, offers a new way to think about vaginas (albeit avian ones). Scientists have long expressed awe over the male duck’s unexpectedly long, coiled member. But until Brennan, no one had bothered to examine the female side of things. The duck vagina, she revealed, was a biological marvel: a strategic maze of dead ends and blind pouches that worked to foil the male and render unwanted sperm impotent. It was no one-size-fits-all penis holder, but an organ specially adapted over millennia to execute its own goals.

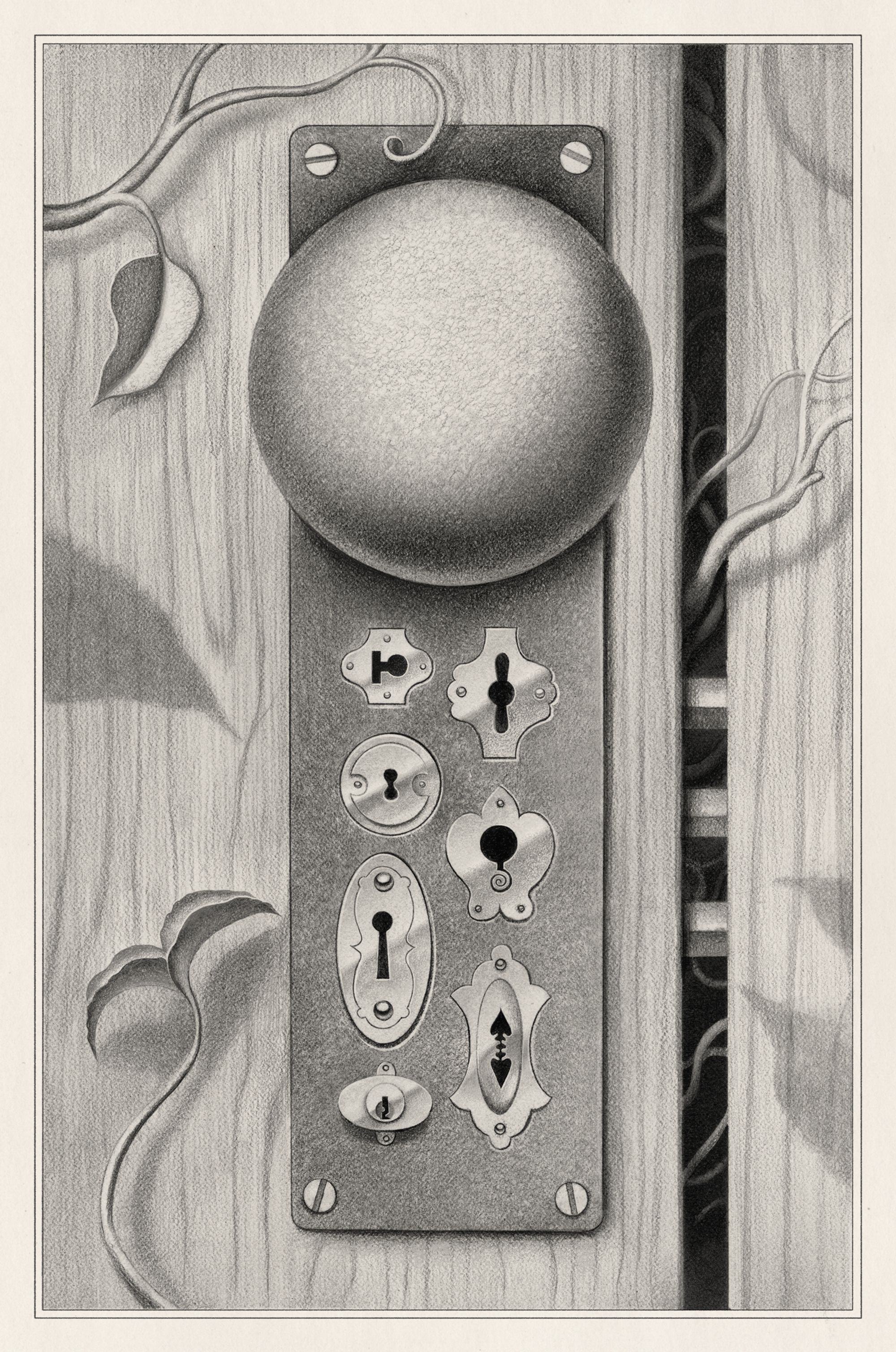

Given that not all vaginas are quite so, er, oppositional, what could account for the stunning diversity of animal genitals? One explanation in the literature was the idea of “lock-and-key,” a Darwinian maxim that states that males and females of each species evolve so that their genitals fit only into each other’s. It was nature’s form of two-step authentication, a way of telling you that maybe it wasn’t such a good idea to proceed. Yet to me, that seemed overly reductive. Once again, it presented the male as the active component (the key), and the female as a means to an end (the lock).

Armando seized on the imagery of locks and keys, but switched the perspective. We wanted to see what would happen when we centered the female—the “lock”—instead.

I loved the chapter on animal vaginas. I was amazed to learn that certain animals like ducks had evolved complex corkscrew vaginas to block male penises. This image grew out of the “lock-and-key” theory of evolutionary biology, which we agreed to be limiting since it reinforced negative associations with vaginas as passive. Instead, I wanted to reframe this image sans key, and focus on a lock that conveyed the complexity, resilience, and power I found in the duck. As I was developing my idea for this chapter, I thought of that strange scene in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, in which Alice encounters a stubborn, talking doorknob who seems determined to remain locked.

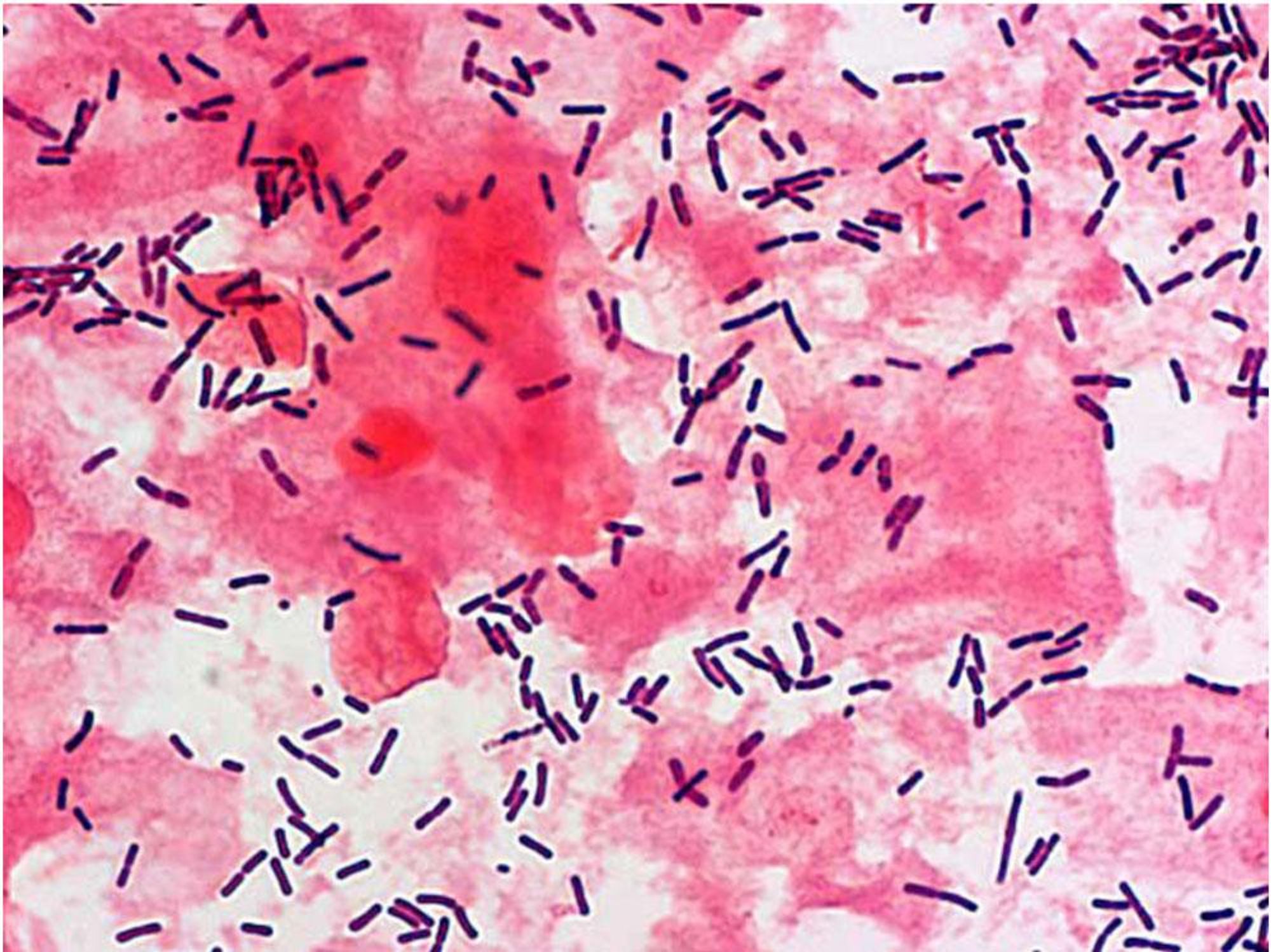

Besides passivity and negative space, another idea that has attached itself to the female body for millennia is purity. The misguided idea that the vagina should be spotlessly clean and sterile is what led to the rise of products like vaginal cleansers, pH “balancers,” and douches—which can in fact strip the vagina of its natural protection, making it more susceptible to disbalance. In this quest for cleanliness, vaginas that teem with life have often been viewed as unhealthy.

But the emerging science of the vaginal microbiome has taught us that a healthy vagina is actually an ecosystem teeming with bacterial communities that work together in harmony. Certain rod-shaped ones, known as lactobacilli, are keystone species, sculpting the environmental niche needed for the vagina to maintain health and balance by spewing out lactic acid.

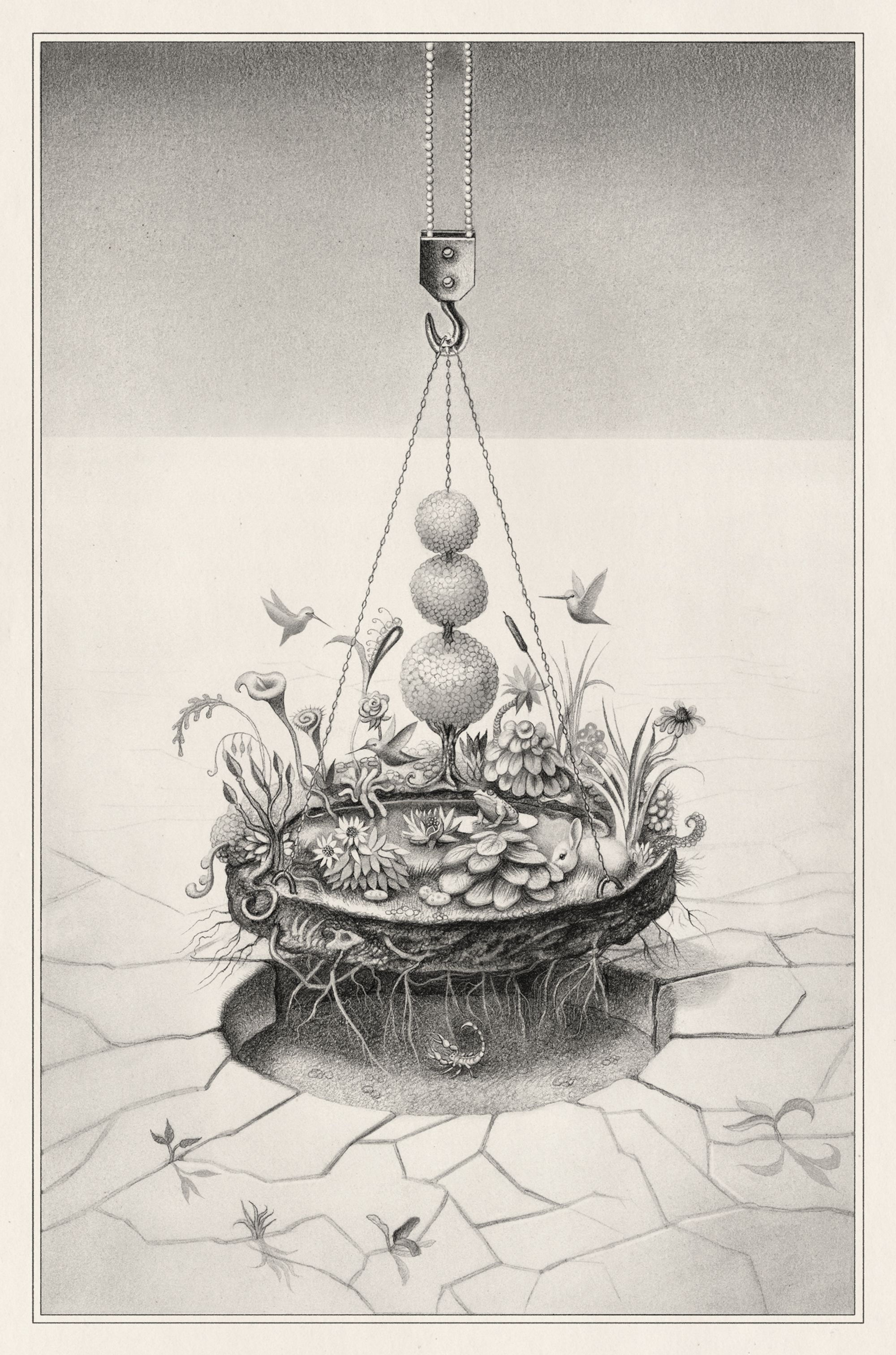

I felt myself drawn to images that described this intimate ecosystem not as a battleground but as a dynamic garden: a rich mixture of different species, overflowing with weeds and flowers both native and novel. None of these tenants are inherently good or bad; they simply are. Nor is this landscape a static one. The vagina is constantly changing in response to a shifting environment, adapting and righting itself whenever something knocks it off-kilter. To paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir: your vagina is not a thing; it is a situation. Its resilience is part of its power.

In describing the world of Vagina Obscura, Rachel painted a dynamic landscape brimming with microbes that nourish, protect, and maintain a balanced ecosystem. I imagined piles of lush flora with squid-like tentacles that reach towards the sky, and deep subterranean roots that weave and sway to an ancient tune. Teams of microbes, like farmers, investigate the land and plant seeds. Their microscopic cranes harvest and delicately rearrange the landscape to reestablish balance in this transforming world.

Down the hill from my studio at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I encountered a curious sculpture: a rock-hard, golden penis balanced on a polished, limestone cube. I later learned the phallic sculpture by Constantin Brancusi, titled “Princess X,” was actually a bust commissioned by Princess Marie Bonaparte. Apparently, it was intended to feature the head, neck and bust of a female client.

In Vagina Obscura, I learned of the real Marie Bonaparte, an early 20th century noblewoman and trailblazing sex researcher. She surveyed hundreds of women and published studies to better understand the clitoris. Ultimately, she even experimented on her own through a series of surgical procedures in a quest towards greater (socially accepted) pleasure.

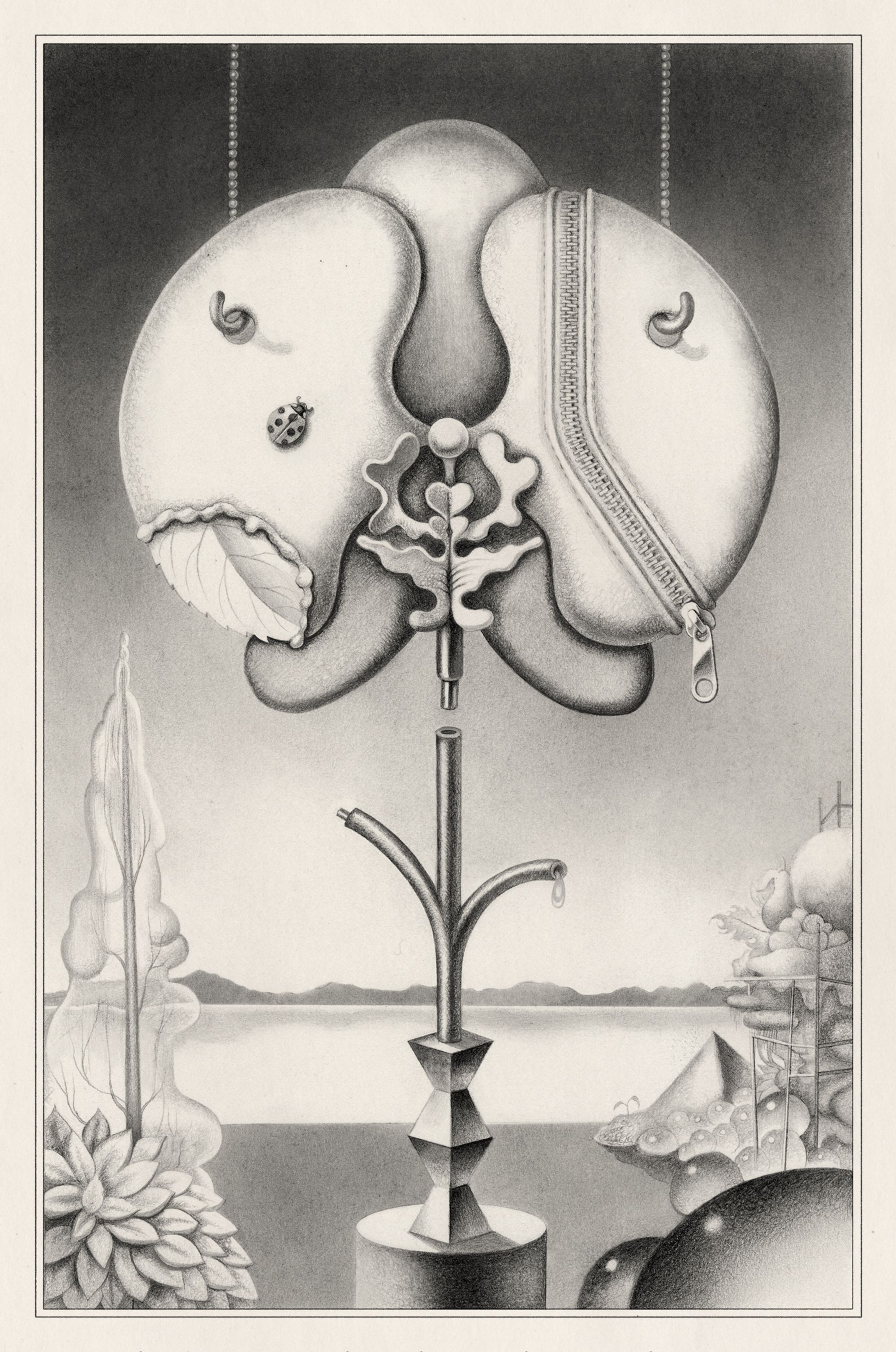

This sculpture’s likeness to a penis may be mere coincidence, but I was fascinated by the sexual duality embodied by this object. I again encountered this kind of duality in orchids, which contain both male and female sex organs. For Rachel’s final chapter, I wanted to construct an image that also embodied this duality—a monument to our shared anatomy.

The orchid that helped inspire Armando’s final, iconic image has more to offer than meets the eye. In talking to surgeons who perform gender affirmation procedures, I learned the term “orchidectomy,” a procedure which removes the testes. While I’d always thought of these flowers as uniquely vulval in nature, the word “orchid” actually derives from the Latin for testicles, a name that owes to their tuberous roots. Get yourself a plant who can do both!

For me, orchids became a symbol of the blurred—and increasingly blurring—boundaries between the sexes, highlighting how much of this anatomy is actually overlapping. I would later find out that, for this very reason, orchids have become an important symbol of the intersex community. Gender affirmation procedures rely on these inherent similarities to help reshape “male” genitals into “female” ones. In reality, all bodies share the same origin in the womb, the same universal body plan, and deep anatomical similarities that continue into adulthood.

During one of our early brainstorms, Armando said something that stuck with me: “Illustration has no gender.” I realized then that our goal wasn’t necessarily to show these body parts from a “feminine” perspective, whatever that would mean. Nor was it to locate some “pure,” objective, scientific truth within the female body. Acknowledging that science is always done by human beings with distinct values, we sought to re-chart these territories from our own starting point of curiosity and wonder—unbound from past associations, embracing change, and most of all, celebrating the boundless diversity and shared anatomy of all bodies. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast