13 Ways of Looking: Lauren Groff

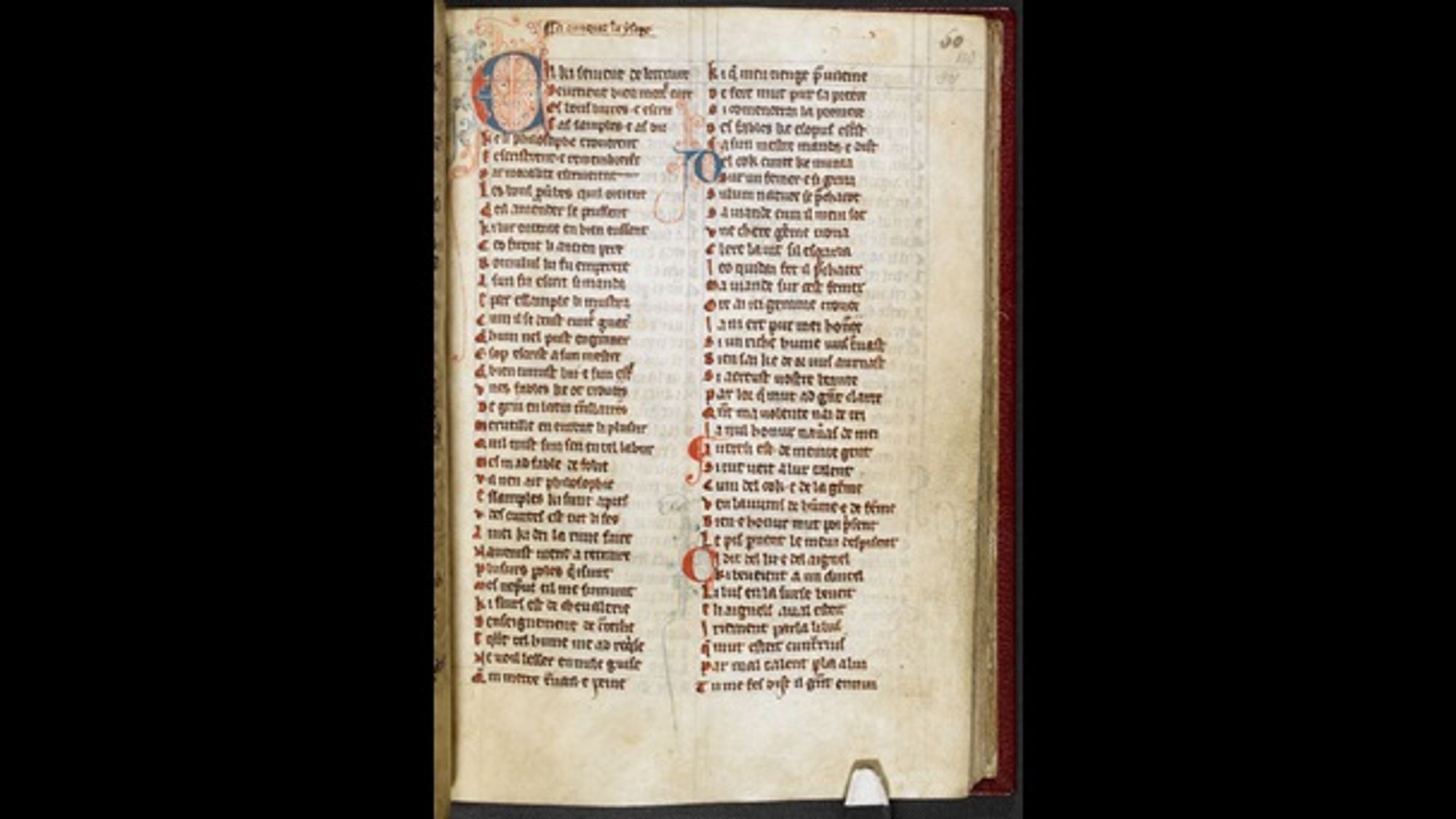

The seeds for Matrix were sown over twenty years ago in college, when, after taking two tutorials in ancien français, I was for a long time besotted with medieval narratives. My favorites were the Lais of Marie de France, a shadowy figure we don’t know much about but who may or may not have been the French abbess of an English monastery; I’ve returned to the text over and over in the decades since. The sight of this manuscript page starts an avalanche of internal images from the lais.

I’ve also been wildly, and separately, excited by mysticism over these years, particularly the ways in which female mystics used their visions to create autonomous spaces for themselves within tight and often hostile hierarchical strictures. I’ve loved Julian of Norwich, Mechtild of Magdeberg (The Flowing Light of the Godhead!), Margery Kempe, and my very favorite of all, Hildegard of Bingen, who was a genius in about many different directions, including music, medicine, and the organization of communities. This is an image of Hildegard.

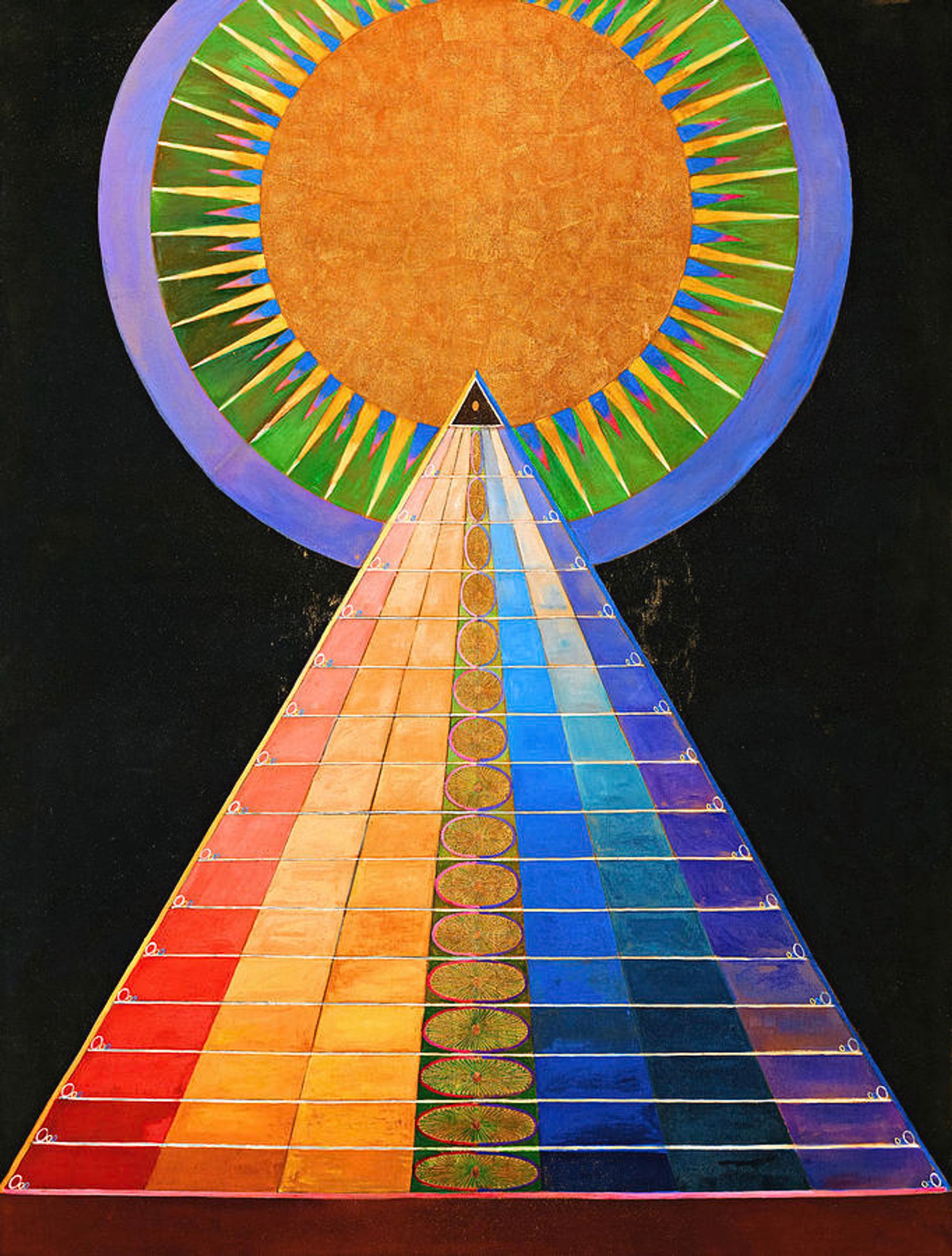

One of my favorite modern mystics was Hilma af Klint, whose Guggenheim show “Paintings for the Future” I saw in 2018, and it knocked me to my knees; I’ve had a postcard of this painting hanging by my desk ever since, and I think it primed my subconscious to begin thinking on a daily basis about mysticism and spirituality; I wanted to write a book that felt the way this painting, Group X, Altarpiece 1, feels to me.

These old interests collided and exploded when I sat in on a lecture on the liturgical practices of medieval nuns by my friend Dr. Katie Bugyis at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies, in which she spoke of the many ways the nuns practiced autonomy through their relationships with their liturgical manuscripts. One of the images Katie showed was this, the discovered teeth of a medieval nun that were stained with lapis lazuli, an extremely expensive blue mineral used in illuminating manuscripts, possibly indicating that nuns were engaged in this work that for a long time had been assumed to be the province of men.

While I did my research, I was frequently astonished by the wildness and humor of some of the marginalia on medieval manuscripts. There is a tradition of little doodles called drolleries that were hysterical—think nuns plucking penises from trees, archers shooting mermen in the butt, subversive and strange little images. My favorites were the pictures of rabbits (often associated with feminine docility and fertility) suddenly turning violent.

I surrounded myself with images from the era, to try to understand a sense of the medieval visual perspective. I spent endless hours just looking at the Bayeux Tapestry, which you can scroll through on Wikipedia from your own house, even in the middle of a global pandemic. It’s a spectacular work of collective (almost certainly female) artistry, commissioned by the Normans as apologia for the Norman conquest. Nobody knows quite who commissioned it, but I like the supposition that it was Empress Matilda. Of the panels, the one I love the most is this, of a lady named Ælfgyva (or in medieval English Ælfgifu, the gift of the elves) being glad-handed by a cleric: it’s mysterious and strange and wonderful.

I read a large number of books about the era, then, to give myself a little vacation, watched the film The Lion in Winter to think about Eleanor of Aquitaine. Oddly, Katharine Hepburn didn’t suggest Eleanor to me, but rather some hardness and fire in her personality showed me the way into my abbess, Marie. I then watched a very weird George Cukor film called Sylvia Scarlett, and though Hepburn is far too exquisitely beautiful for Marie, her forcefulness and androgyny in the film gave me even more insight into my Marie.

In the process of researching falconry, a sport of the nobility at the time open to women, I must have watched this clip a hundred times. Some of these visual cues act in an indirect way, or they semaphore a kind of inexplicable emotional abstraction, and it took me until now to understand what I took from it: a certain kind of ferocity, clear-sightedness, high-stakes flying that I think I wanted the character of Eleanor of Aquitaine to have.

Because I couldn’t pin the video to the wall, I printed out this detail of a peregrine falcon from a 13th century manuscript.

I realized that the closest I would come to the actual figure of Eleanor was to the effigy of her on her tomb, and when I was at a loss, I would frequently go back to look at it. I understand now why people visit cemeteries to speak to their beloved dead.

Halfway through the first draft, I read the apocryphal story that Henry II placed Rosamund Clifford, his mistress, at the center of a labyrinth to keep her safe from his wife Eleanor; soon after, with the synchronicity that novel-writing often opens up, I began to see labyrinths everywhere in the world. This was my cue to research in this direction, and when I saw (again, onscreen; I’d seen it before in real life) the labyrinth in the Cathedral of Chartres, I had chills. I knew it would be a huge part of my book, at first in a plot-wise direction; eventually, after a few drafts, it also became the secret structural foundation of the book itself.

While in the thick of research, I read this article in the New York Times about how, with climate change, the scorched fields of Britain began to offer up the ghosts of long-lost structures, impressed upon the grass from below. I felt ill and moved and astonished, all at once. This became one of the larger overriding metaphors for my book, which is perhaps not visible to the reader, but is important to me. This is a prehistoric ceremonial landscape showing itself to living eyes.

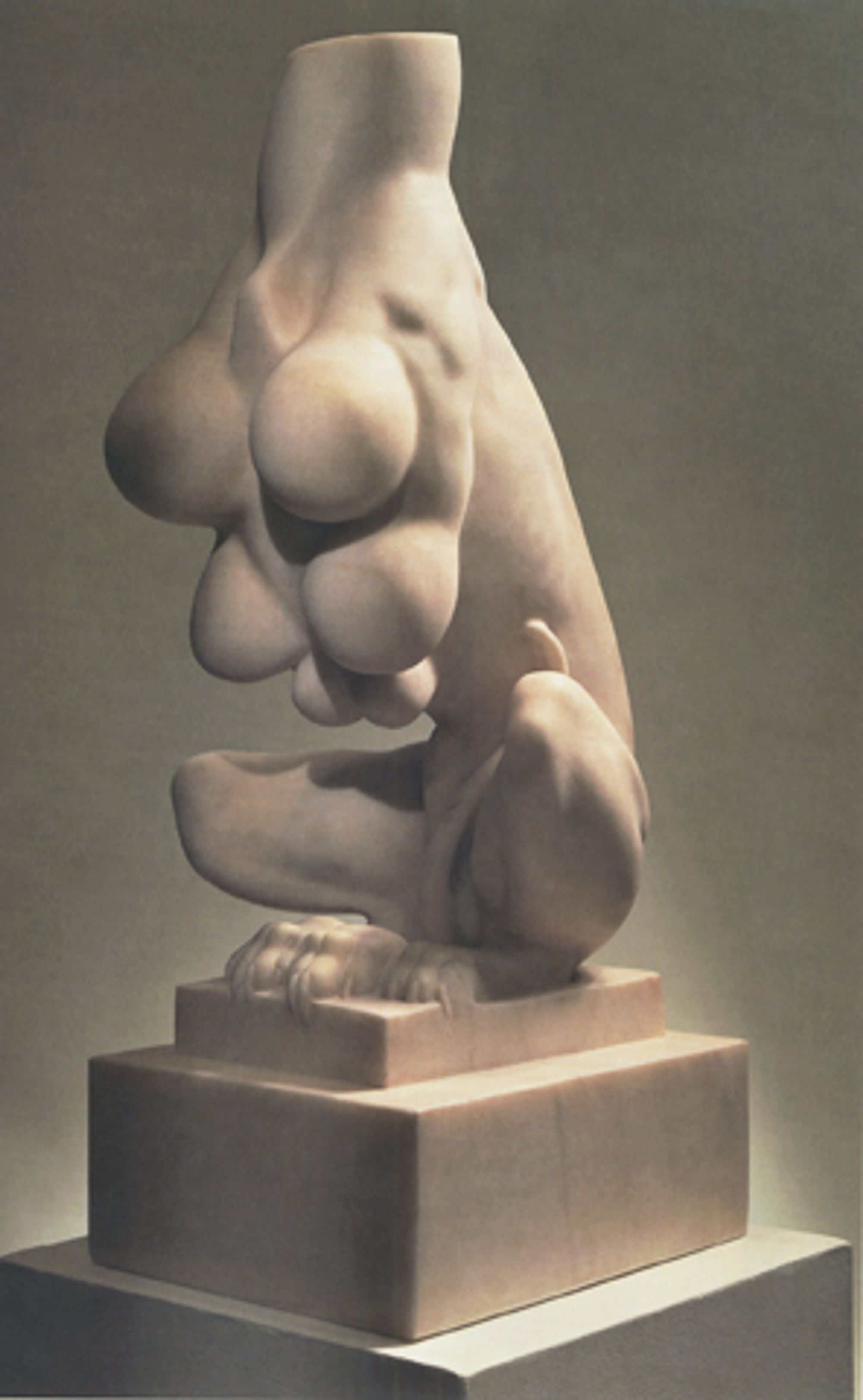

Louise Bourgeois hangs over this book in strange and inexplicable ways: I printed out the image of this sculpture, Nature Study, because I wanted it to speak sotto voce in its own vocabulary of sheer animal lust and beauty back into the book. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast