13 Ways of Looking: Hua Hsu

I began writing some of the sentences in Stay True twenty-four years ago, the night my friends and I found out that we had lost Ken. Most of us were juniors; I’d just turned twenty-one a few weeks earlier. At the time, it never would have occurred to me that I was writing a book or that I would become a writer at all. I was just taking notes in order to have something to do, to soothe myself, to catalog all of our minor adventures or inside jokes so that I would never forget. I wrote about the past, and I wrote about those first few days in meticulous detail because it was a way to avoid actually being present. Exploring memories was a way of forestalling the future, and it brought calm to retreat to the page.

I’ve always been a sentimental person who finds comfort in being surrounded by stuff—books, records, trinkets, posters, commemorative T-shirts, photographs. But my fascination with keepsakes and mementos took on a different shape after Ken’s death. I kept this old, padded mailer full of things I associated with him: receipts, bottle caps, notes scrawled on napkins, a boarding pass for our trip to San Diego for his funeral, the last pack of cigarettes we ever smoked. Over the years, this envelope took on a talismanic meaning to me. It was as though these things were clues, and if I arranged them correctly, if I held them to the light just so, I would figure something out.

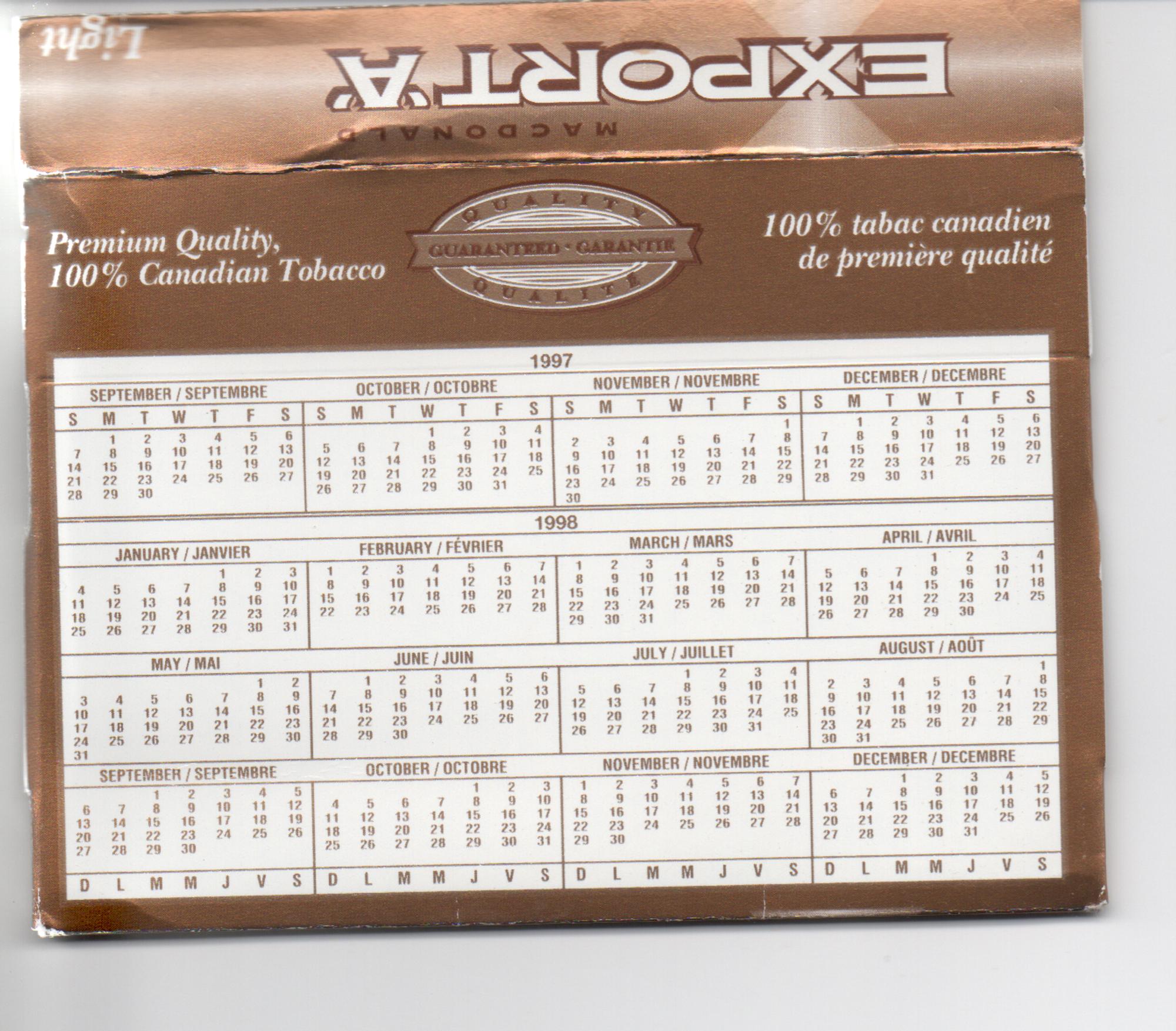

What could any of these things actually reveal that I did not already know? I always found it strange that Export ‘A’ cigarettes included a calendar in their packaging. On the one hand, it felt so grown up—as though we had somewhere to be, plans to make, a reason to think beyond next weekend. On the other hand, it was morbid to be reminded of passing time while we diminished our lung capacity, numbering our days in a literal way with each theatrical drag.

I just looked it up. Apparently the calendars date back to a time when Export ‘A’, a Canadian brand, distinguished themselves from competitors by printing hockey schedules on their packs.

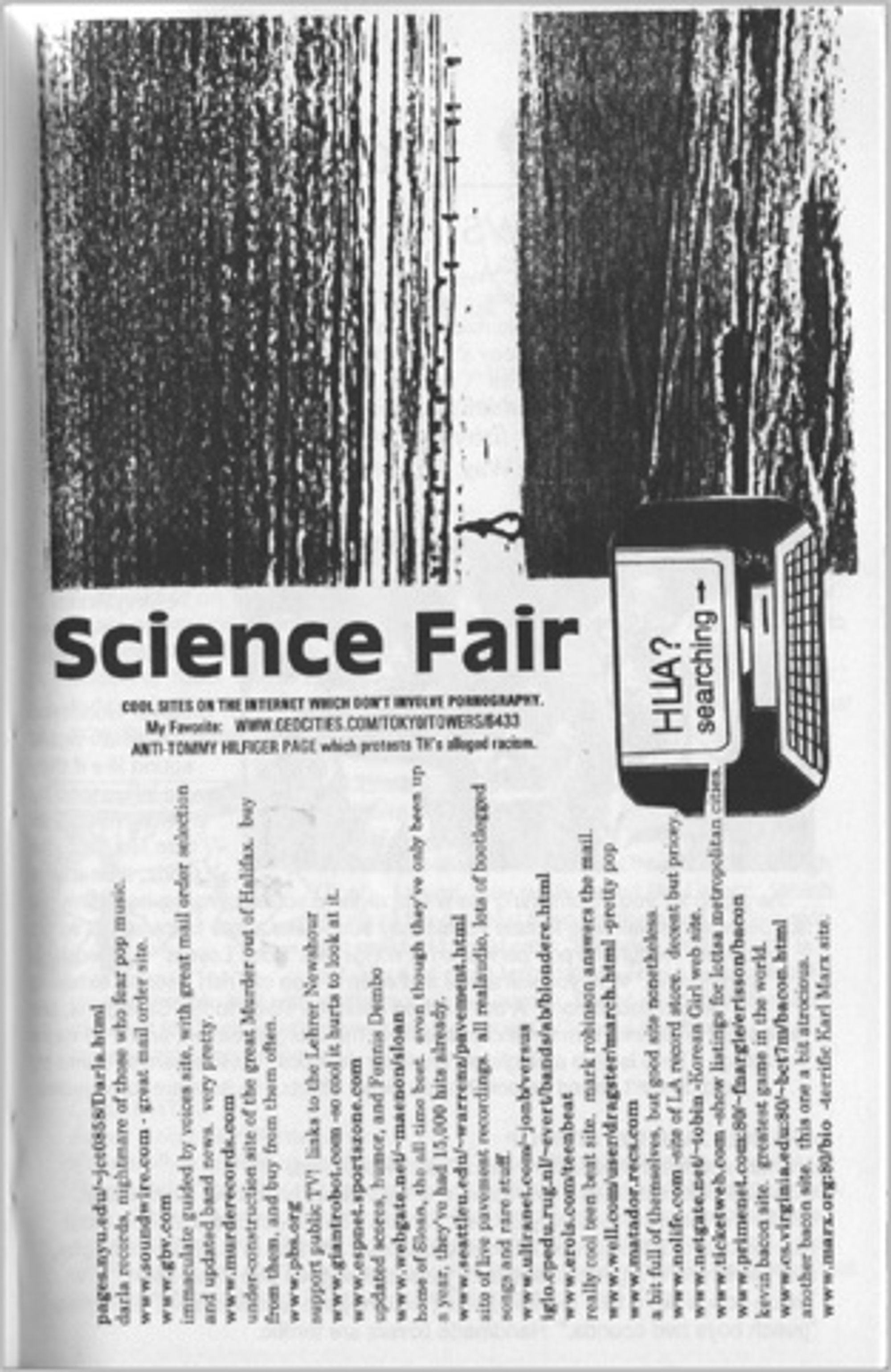

I wonder how many of the small mysteries we pondered in college could have been resolved quickly with access to Google. Rather than debating other people’s theories about The X-Files, we advanced our own. Without any comprehensive list of obscure ’80s and ’90s network sitcoms, we did it ourselves. When you’re young, boredom is the crucible of friendship—you’re just looking for ways to pass the time. And there was only so much time you could pass on the circa-mid-’90s Internet. It felt manageably vast, yet it wasn’t to be taken too seriously, as I discovered when I would uncritically forward messages about easily-debunked conspiracies to my Berkeley comrades. Web pages would come and go randomly, and if you accidentally deleted your emails, they were lost forever. Instead, we would spend hours trolling conservatives in an AOL chat room. I always thought my friends—Ken, Ben, Sean, sometimes Anthony—were sacrificing something spending Friday nights that way. For an issue of my zine—a xeroxed, scissors-and-tape affair I would leave around Berkeley coffee shops—I compiled a list of my favorite websites:

Back then, we rarely took pictures. It was obtrusive—it wasn’t until my thirties that you could comfortably carry a camera around in your pocket. Developing film was labor-intensive and costly. But even at the time, there was a delight in the lag between when you took a picture and when you held it in your hands—sometimes it would be weeks or months later. I visited Ken in San Diego one winter, and while he was buying cigarettes at 7-Eleven, I leaned out the window and took this photo. I thought it would look cool in my zine—there was something about the way this generic, corporate sign looked on this night, against this sky, out the window of this car. I have no other photos from the trip because, I thought, who needs a photo of someone you see all the time.

When it came time to lay out the book, my brilliant editor, Thomas, suggested including images like this one. Our common reference point was the late German writer W. G. Sebald, whose restless, relentless writing is often broken up by small, inset photos. I am not at all comparing myself to Sebald. But the use of images in his books make the lives and events he describes feel real, even though, as I would find out many years later, many of these histories were invented. This didn’t make them feel any less “true.”

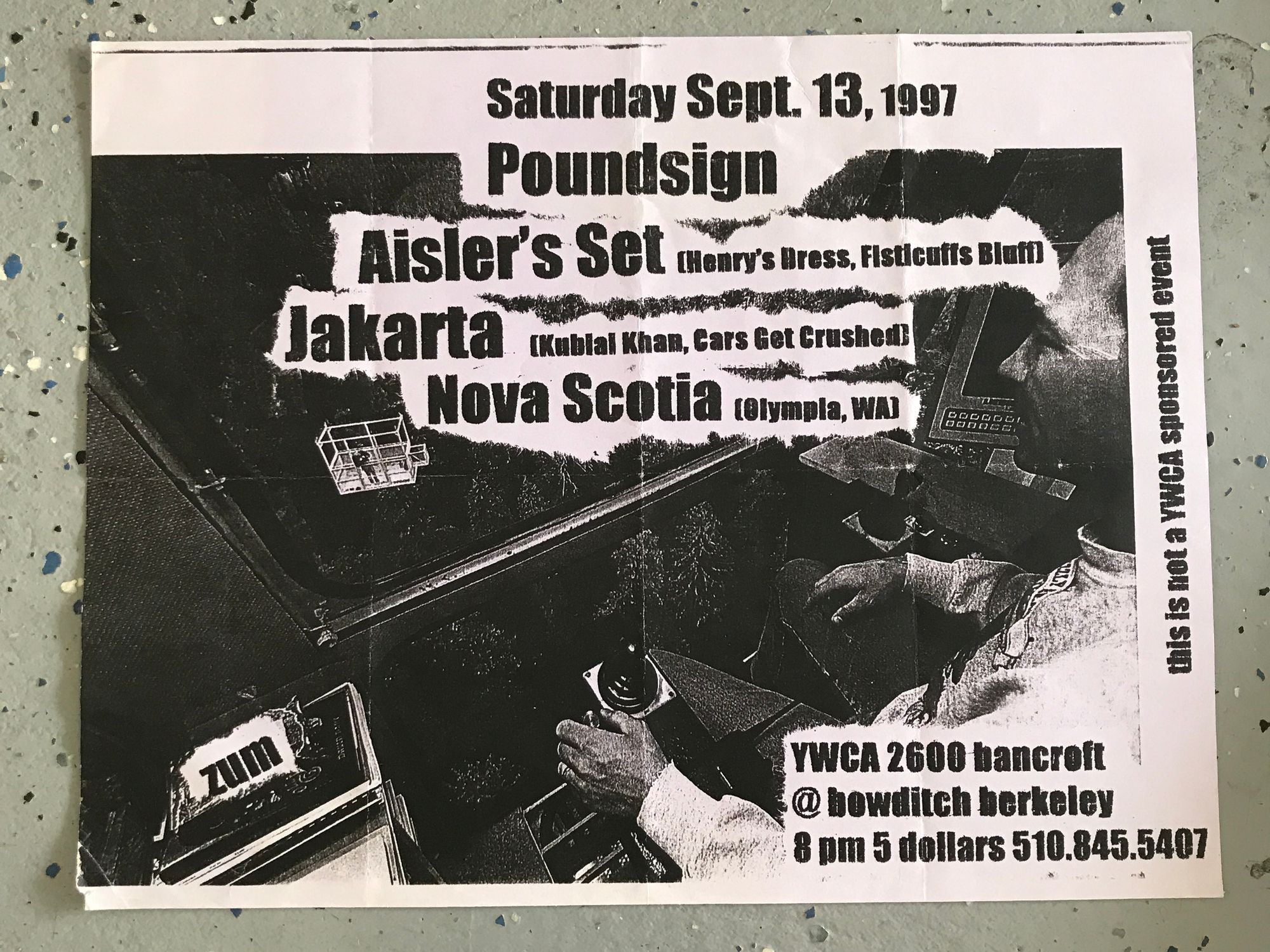

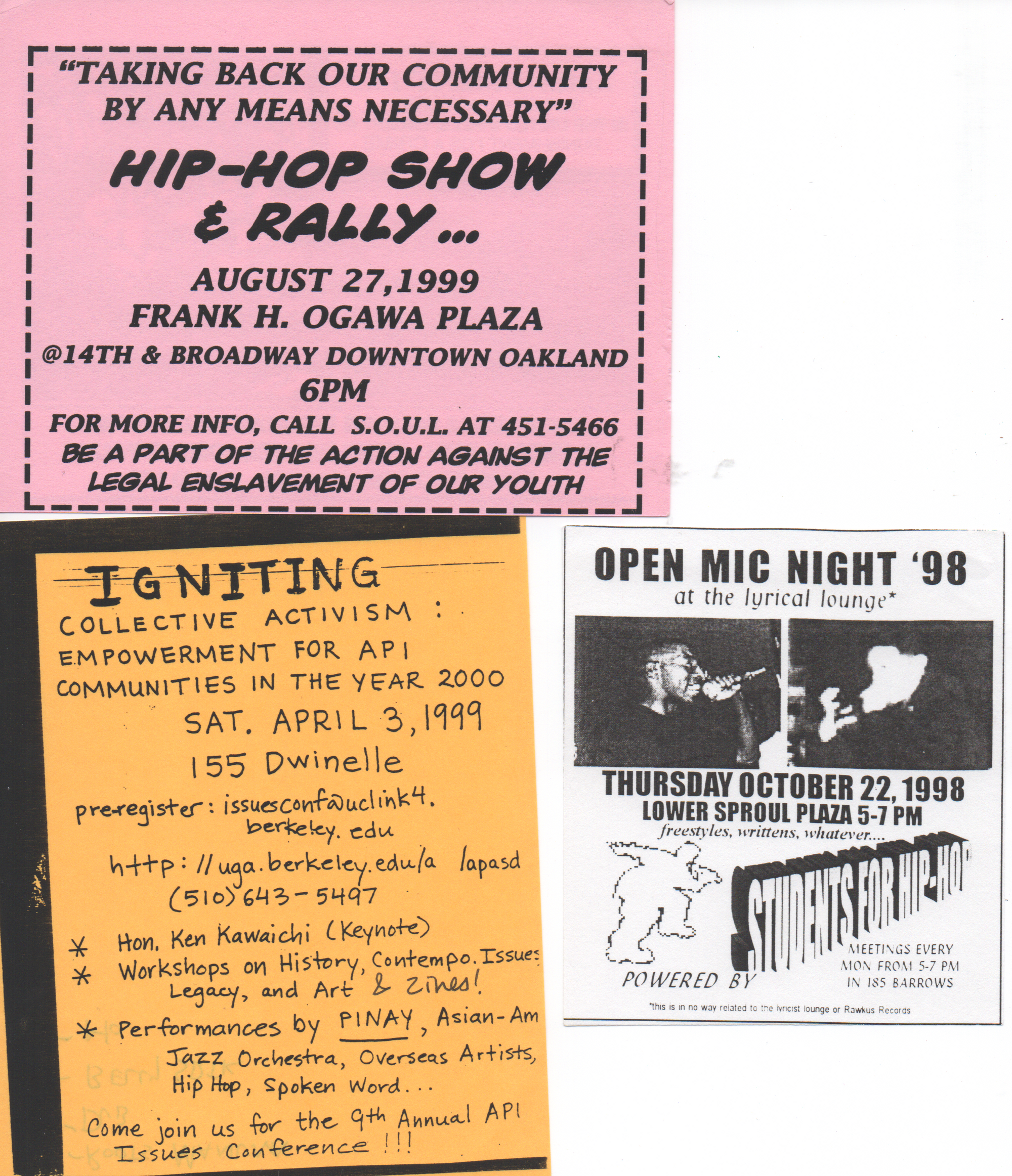

Stay True doesn’t have “chapters,” and the sections aren’t numbered or named, so initially I thought of using the images as a way of breaking up the text. There are moments of doubt in my book—again, not Sebaldian! It’s more about the fallacy of memory, of withdrawing into a state of being “stuck in the past.” But I like how the images in the book—photos, scans of old posters and flyers—offer fleeting glimpses into the past without feeling like specimens. It’s like you’re walking down the corridor of a dorm, peeking into all the open doors, and you see all these different lives as you continue on your way.

The dorms. The great equalizer. Berkeley is a huge school, and that means it’s not as hard to reinvent yourself as it might be at a small college, like the one I teach at now. Four years is eight chances to show up for a new semester with an unprecedented haircut, nickname, or personality. Nobody would ever know this wasn’t who you were before winter recess.

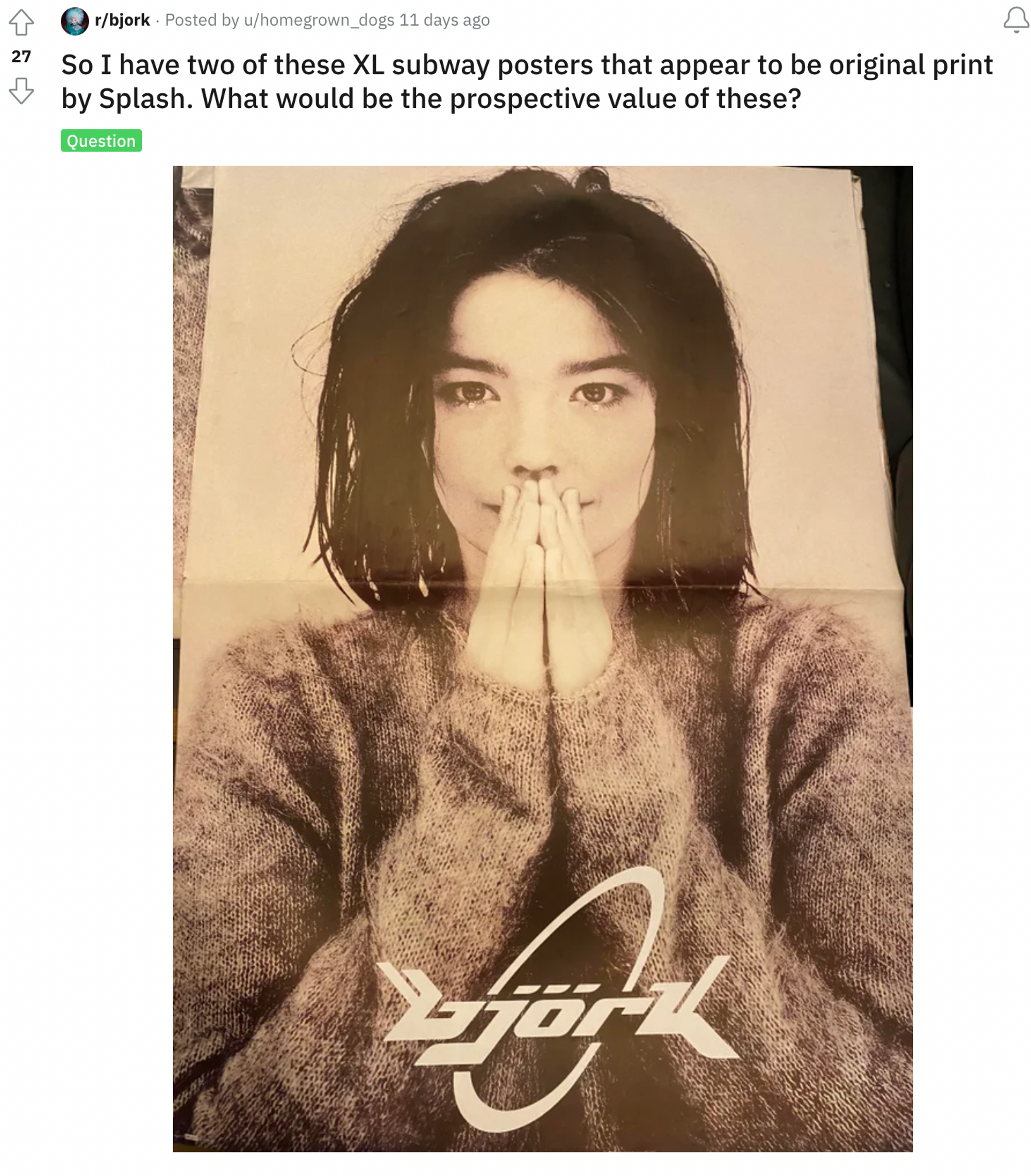

In the beginning, in the dorms, I immediately sorted everyone according to taste—what they had on their walls. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t think to give Ken a chance when we first met—he was too “mainstream.” His room was decorated with photos of his high school glories. But I was here in search of new adventures, and the posters on my walls were a form of communication to anyone who might take me away with them. I didn’t have a ton of wall space in my first-year triple, so I hung things on the ceiling, inches above my bunk. One of the first posters I bought upon arriving at Berkeley was a Björk “subway poster.” I had never been on a subway and I did not know what a “subway poster” could possibly be. It turned out it was the size of my entire bed, her forehead was as big as my pillow. I slept underneath it for a few days before it began to terrify me.

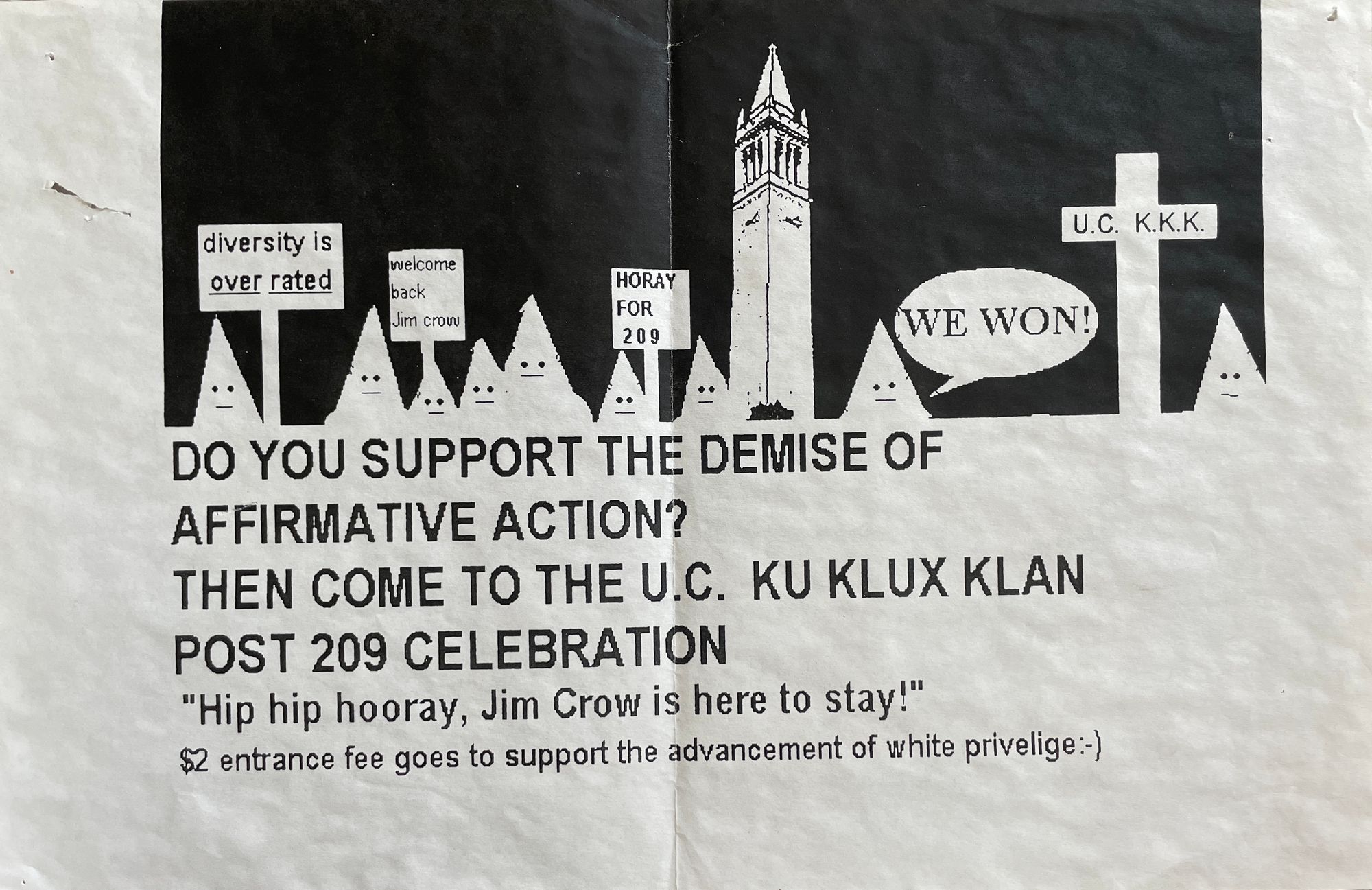

I eventually downgraded to smaller magazine cut-outs. Throughout college, my walls were like a constantly changing bulletin board of whatever was going on that week. It was like a projection of my interests, and refreshing my walls was a way of exploring new facets of who I thought I was becoming. I would hang protest leaflets,

gig flyers,

Xerox “art,” or mock-ups for my zine. I think this is a close-up of a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy for a benefit reading for Assata Shakur.

I was always looking for material for my zine. Why did I ever write before this? It was to bring a self into focus. It was a distress signal—who will rescue me from boredom? Sounding the deep. If I’m honest, it was also for the free CDs I promised record labels I’d review. But I measured my own growth by the quality of it—the “insight” (lol) of the writing but also its aesthetic. Like when I finally got a scanner and started copying the graphic design of magazines I adored, like Giant Robot and Ray Gun.

The future was coming into focus for many of my friends. A vast majority of them were going into “business.” Ken had a dream of going to law school “back East”—a funny phrase for a Californian to use. In the absence of any more distinct paths to follow—I told anyone who would listen I wanted to be a “researcher” when I grew up—I even fantasized about becoming a “designer,” whatever that was. I honed my “skills” by making my zine and laying out campus magazines

and flyers.

(Note: I did not do the drawing on the left. Otherwise I would have added “illustrator” to my list of fantasy vocations.)

I had gone to college to look for people who were just like me. My people. There is this path on campus where Asian frat guys in matching, embroidered coaches’ jackets handed out party flyers. I remember this one time, a guy handed me a flyer and then looked at me, quickly judging my posture, gait, and thrifted clothes, and pulled it back. I thought it was hilarious—I wasn’t offended, I wouldn’t have wasted a flyer on me, either. We were members of different tribes. I drove an old Volvo decorated with bumper stickers for indie bands. He probably drove a modified Integra.

Then again, maybe we weren’t all that different. Perhaps, in another context, we could have been friends. It’s obvious to me now, but it wasn’t then, that your sense of selfhood needs to be complicated as much as it needs to be complete. That’s what a lot of these things make me think now. Every now and then, a flyer for some show or conference will fall out of some old book by Aristotle or Hannah Arendt I haven’t opened in decades, and I’ll tumble into the past, wondering where I went to eat afterward, what cigarettes I was smoking at the time, whether I went home and wrote about what I saw or heard in my journal.

It was while writing Stay True that I realized all the things I’ve held onto since that time aren’t clues. There’s no mystery. There’s no meaning rooted in the past. But turning these materials and memories into something new—something forward-looking—has changed my relationship to the ruptures of the past, as well as the things I associate with them. For years, they were in a drawer next to my desk. I’ve put all of these photos, flyers, and old zines in a box, and they’re in my closet now. Except this poster, which still hangs on my wall. It reminds me of a moment. But the fonts and colors, the aesthetic and day-glo optimism of ’90s rave graphics, the alien serenity—it reminds me to regard all possible futures, too, even ones that never came. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast