13 Ways of Looking: Kristen Radtke

When I start drawing, my first step is usually scouring through hundreds of images online to get a sense for the framing of what I’d like to draw, or taking a lot of very weird, very ugly photographs myself. Unless I’m just sketching or making a really simple drawing, I need to look at a model or a space to draw it and maintain the right proportions and scale. Here is a sampling of some images I found inspiration from for those drawings, and others that informed the shape of the project in general.

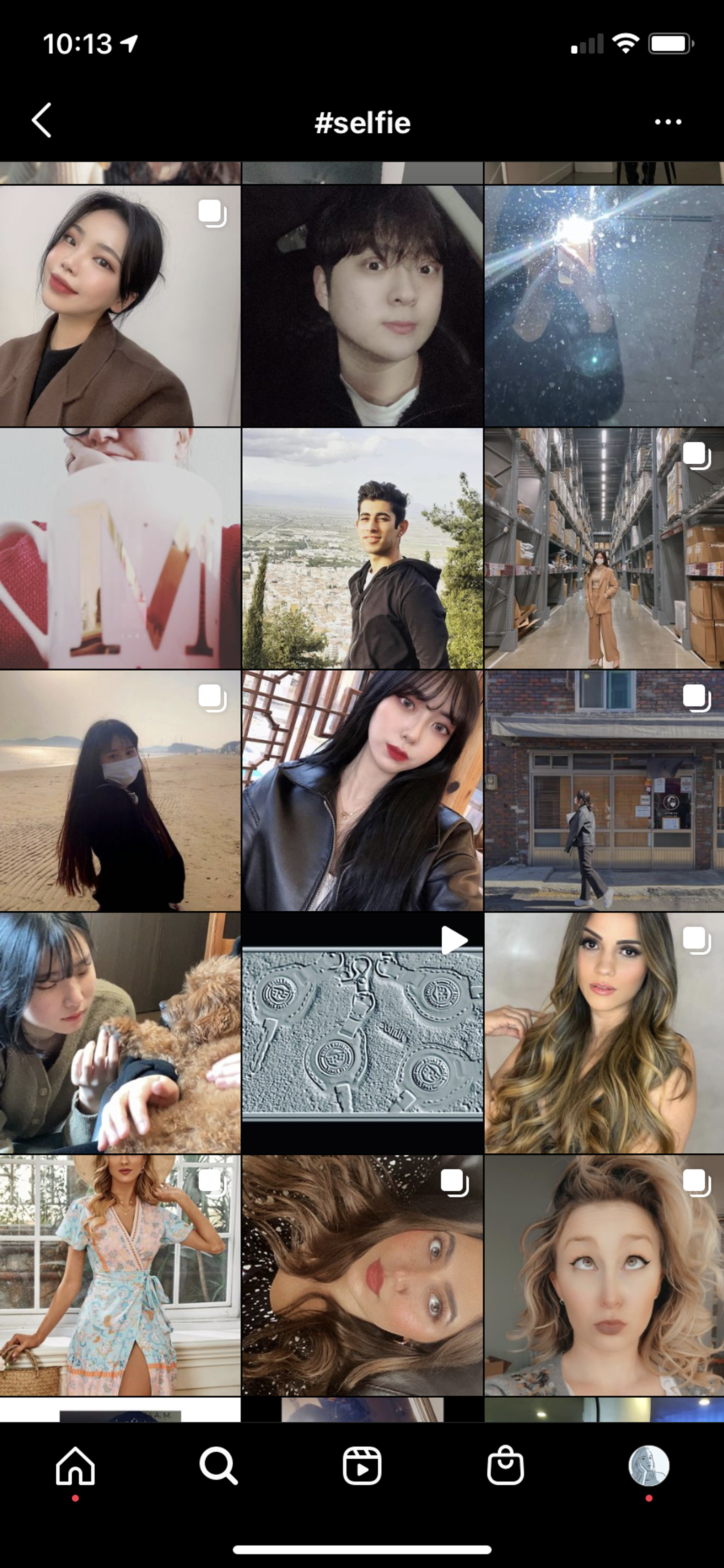

I love everything Yayoi Kusama makes, and I write about her life and art in the book, particularly in relationship to the Instagram age and a critique of selfie culture. This is a selfie I took at her show “Infinity Mirrors,” which I saw in Las Vegas in 2018. Her work is so fun to draw since it’s full of pattern and light, but a comic can only communicate a fraction of the feeling Kusama creates with her large-scale installations in person.

I looked at a lot of photos of monkeys while drawing this book, which contains a section on Harry Harlow, the scientist who became famous for his monkey mother studies, in which rhesus monkeys were raised by inanimate “cloth mothers.” The images are filled with desperation, and I tried to capture some of that in the drawings.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s famous photo series “Heads,” in which he photographed strangers without their knowledge in New York, is such a perfect representation of casual, everyday despondency. I write about this series in the book and found myself returning to his photos again and again.

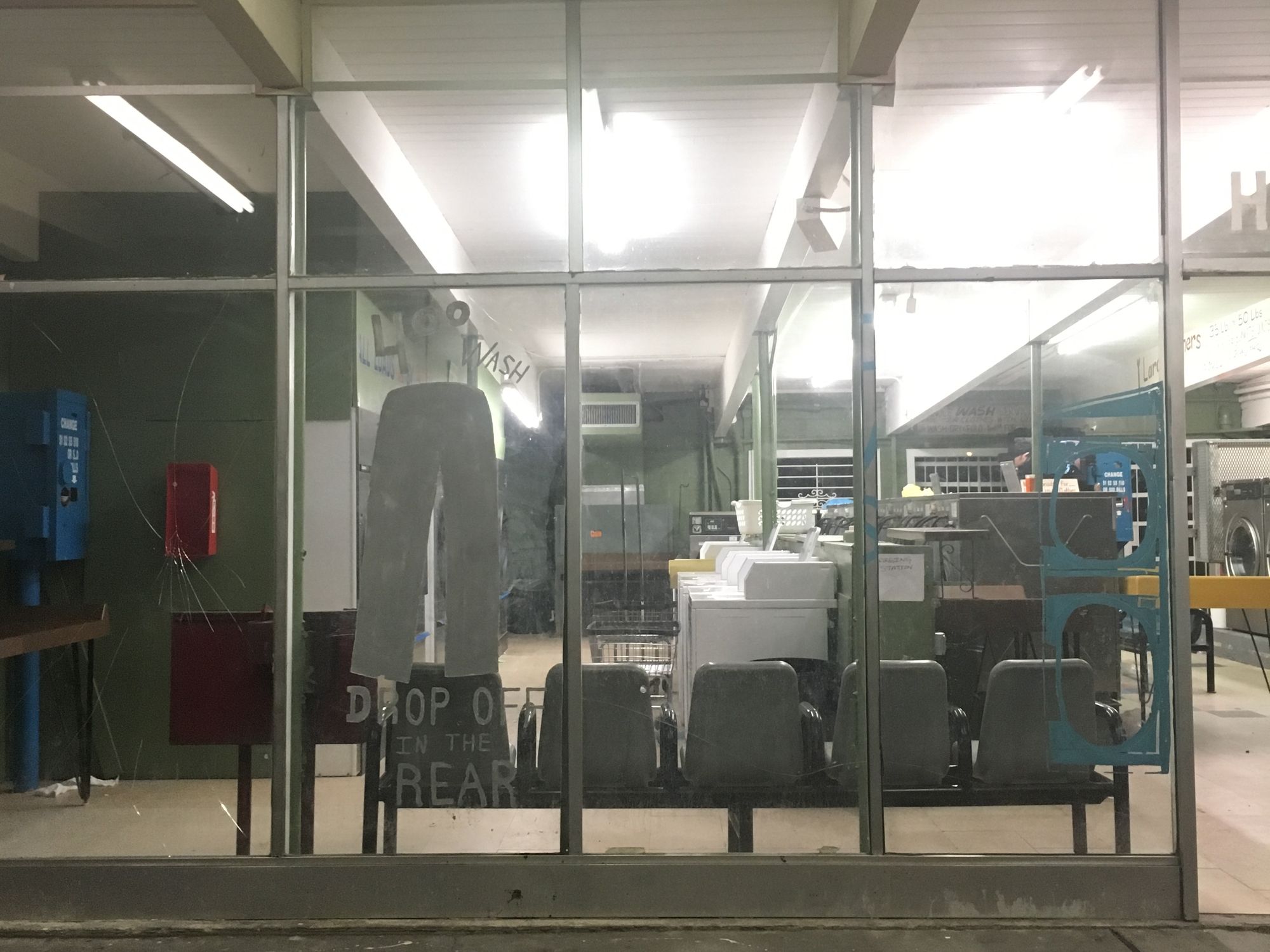

I took a lot of very, very bad photos for years whenever I was walking and saw an emptied public space. They evoke loneliness in a loud, obvious way, as if something has gone terribly wrong. Sometimes I used the photos as drawing references; many hundreds more just live on my iPhone’s camera roll.

Speaking of bad photos, I snapped this shot years ago while I was walking to the subway after an evening at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn. I ended up drawing the scene in Seek You. I love the casual intimacy of the two figures, and how we make spaces for ourselves in New York however we can.

I drew a few different time periods in the book—the 50s, the 90s—which meant digging up a lot of reference images from those times. I loved photos of 90s New York best, especially this one. There’s always something magical about that moment when your subway car passes another car underground between stations, much like catching a glimpse through someone’s apartment window. It’s like you’ve suddenly been granted access to a stage.

Here’s another favorite 90s subway picture. I’ve always loved drawing people on the subway (though have never done it as well as artist Chris Russell and his subway ghosts—no one has!) because the subway provides you access to observe people in a way you don’t get anywhere else. Everyone is still for just a little while.

This is a photo I took during a huge snowstorm in maybe 2015; I think they called it “Snowpocalypse” (but I guess we do that a lot?). I like to draw edges of the city as backgrounds to collage-type pages; winter storms feel both otherworldly and lonely because they make everything go so quiet.

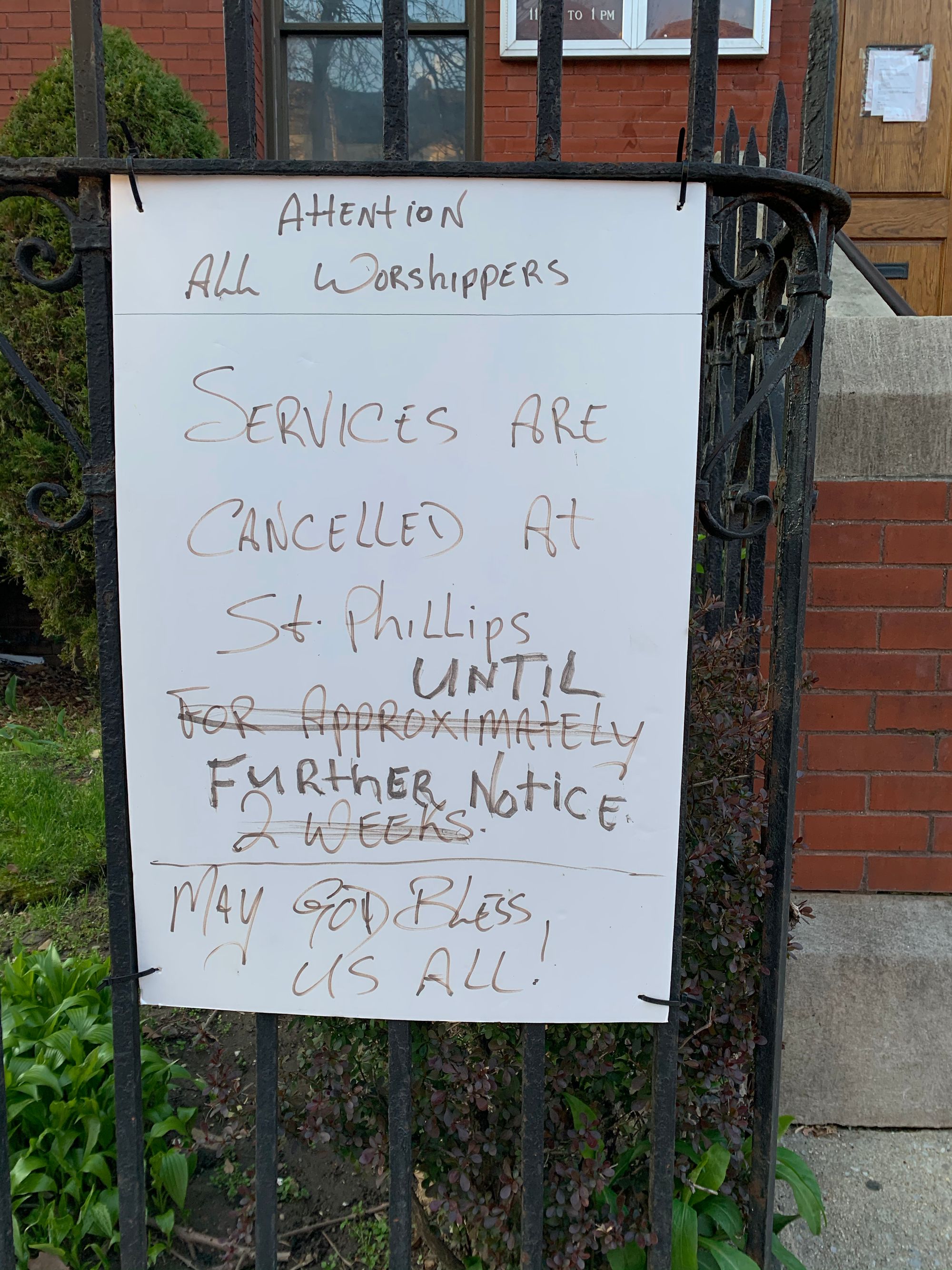

I started writing this book in 2016, but loneliness came starkly into focus in 2020 when the pandemic hit. This sign from a church in Brooklyn really captures those early feelings of what our lives would look like for a long time. I drew this sign along with some images of an emptied New York at the beginning of the book.

I can’t remember when I first stumbled upon Raphael Soyer’s work, but I ended up buying some old catalogues on eBay and spending a lot of time with his images. All the characters in his paintings seem so vacant and isolated, even when they’re not physically alone. This is a painting of Soyer’s parents.

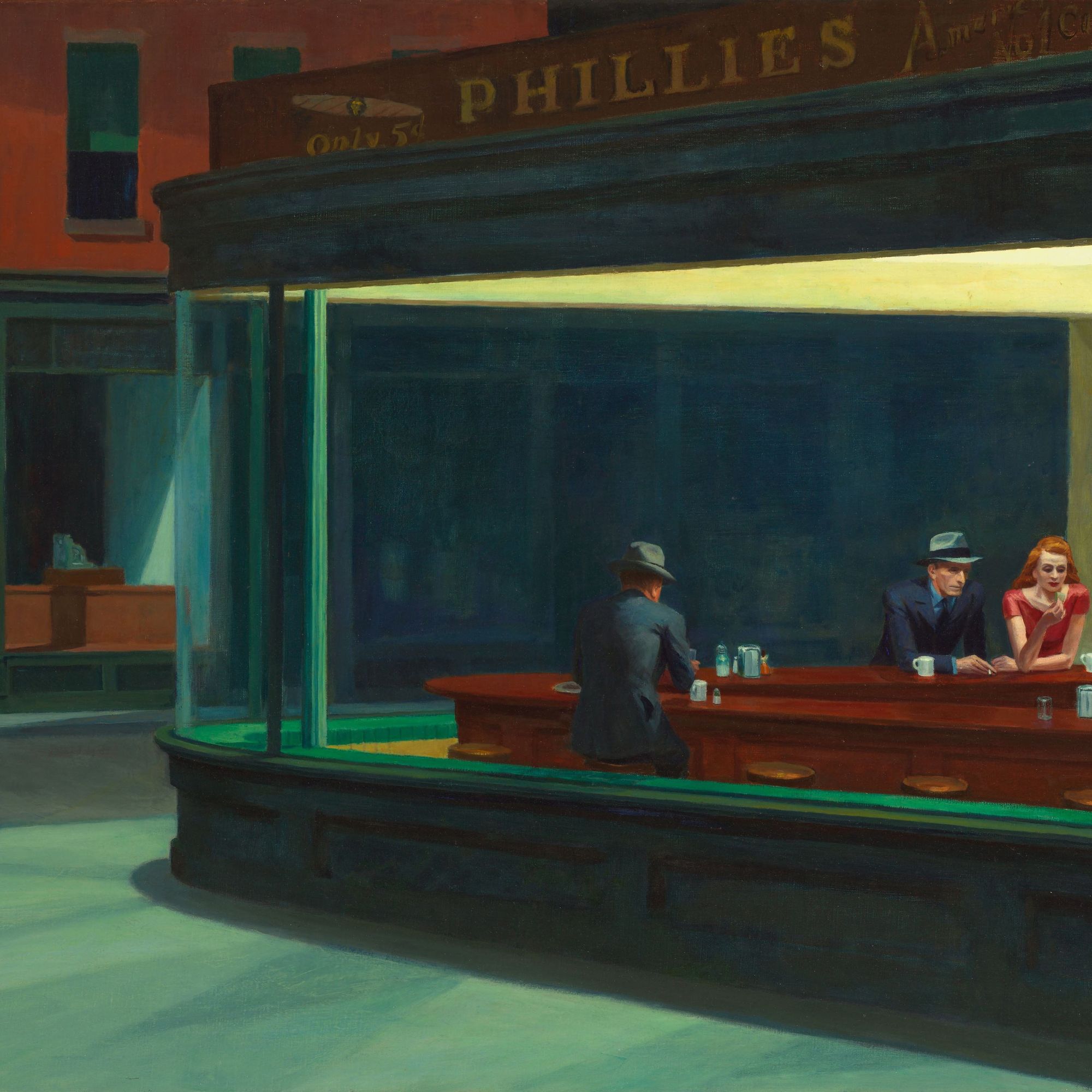

Okay, I was reluctant to include Edward Hopper in a roundup of images about loneliness because 1) it’s obvious, and most crucially, 2) because he was a huge jerk. But he’s certainly the most iconic artist of American loneliness, and his attention to interior/exterior framing certainly had an impact on me.

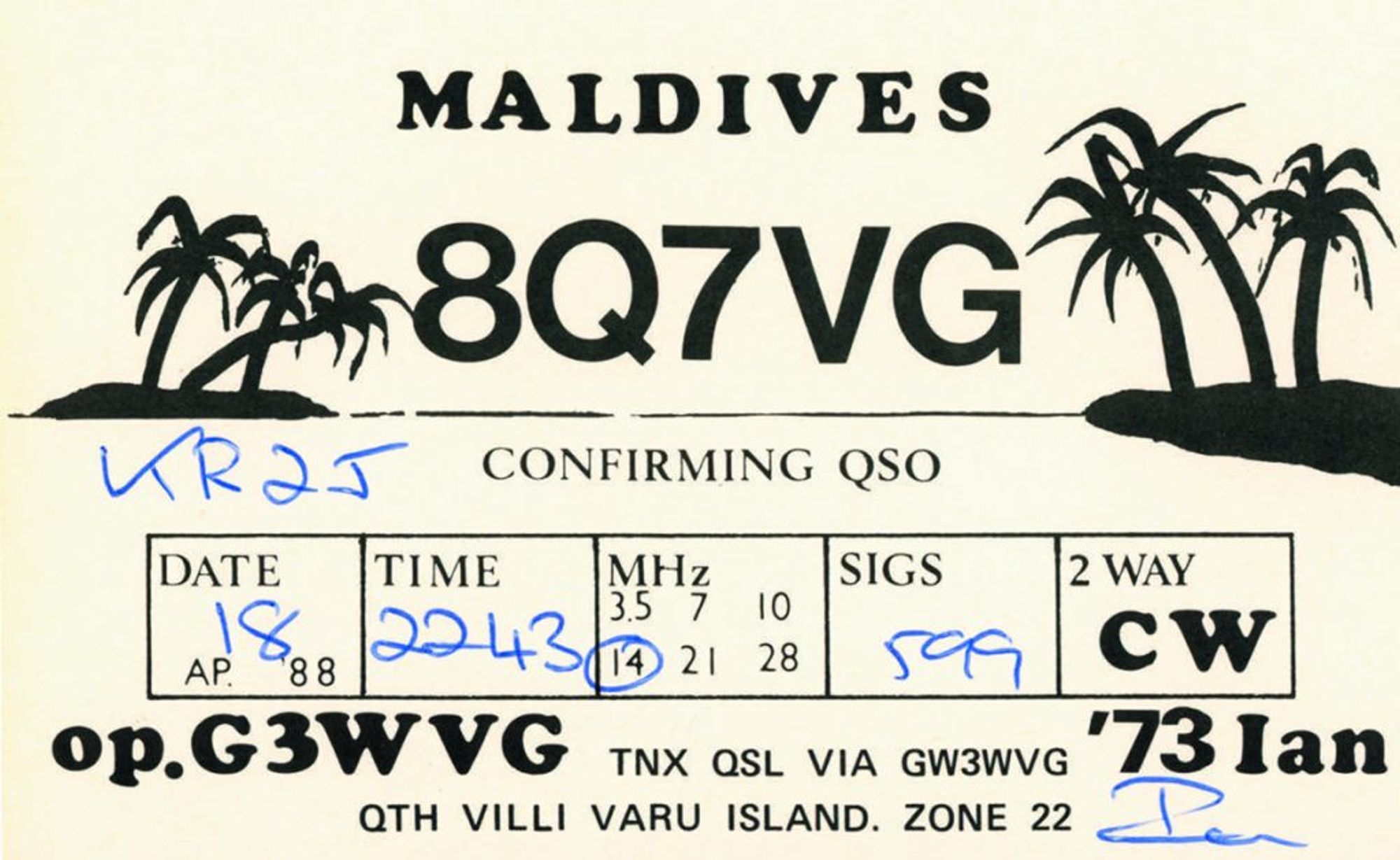

When operators spoke to strangers during the heyday of amateur radio, people often mailed each other QSL cards, which served as a record of their interaction. The book opens with a sequence about amateur radio (which is where the title comes from, it relates to a call that asks “Is there anyone out there?”) and I spent a lot of time looking at photos and scans of decades-old QSL cards.

I referenced Instagram and selfie culture earlier, but I think it warrants its own slide: I couldn’t draw a book about loneliness without spending a great deal of time contemplating Instagram. There are over half a billion selfies tagged with the #selfie hashtag alone, and I’m still fascinated by what it is that encourages us to present ourselves to the Internet in this way. I’m interested in how we ask to be witnessed, and in the way we want to be seen—and by whom.

Subscribe to Broadcast