13 Ways of Looking: Heather McCalden

Book cover of Heather McCalden's The Observable Universe, 2024.

The Observable Universe, my memoir, is both a product of images, and is itself a long image, if a singular image could be stretched through time like a thread of light. The book is written in fragments to induce the feeling of being online and shuttling between browser tabs. It attempts to deconstruct the metaphor “going viral” by tracing the interrelated histories of HIV/AIDS and the Internet. Amid this simulated clicking, my own history emerges: during the early ’90s, my parents died of AIDS.

Images influence text, but they also sustain and nurture the mental processes connected to writing. What follows are examples of images directly connected to The Observable Universe, and images that provided (life) support as I wrote it.

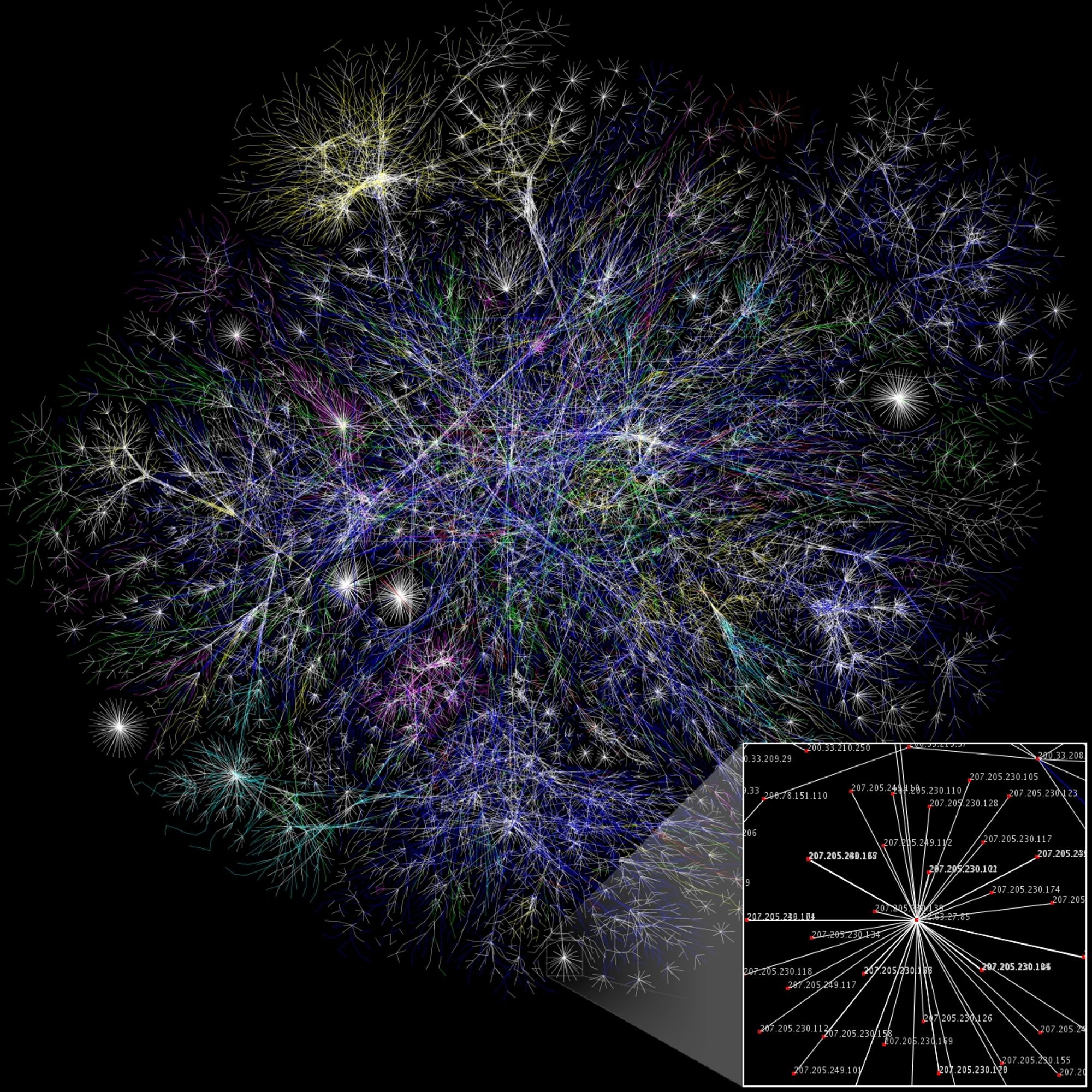

Partial map of the Internet based on the data found on opte.org on January 15, 2005.

Courtesy of Opte and Barrett LyonIn graduate school, I wrote about how the Internet has changed our brains, particularly in terms of narrative cognition. At one point in the text, I set the Opte Project Visualization of the Internet alongside an fMRI scan of the human brain to illustrate the structural similarities between biological and technological networks. Whether this resemblance occurs as a product of chance or unconscious drive, who’s to say. But when I first saw these two images side by side, a lightning bolt had pierced my skull. Their similarities seemed to reveal something about the nature of reality, and I came away with the sense that the Internet, an ocean of textual and graphical information, was closer to the world I was living in than the material one, where people abided by the unidirectional flow of time.

A map of nerve fibers in the adult human brain.

Zeynep M. Saygin, McGovern Institute, MIT.Partial map of the Internet in 2010.

Courtesy of Opte and Barrett LyonLinearity does not exist on the Internet, just as it does not exist in the coral-like vessels of our brains. Online, everything is more or less an image, and you can pluck one out and follow it backwards into history, sideways into fantasy, or nowhere at all.

I wrote about all this in 2014 and 2015. A decade later, is it any wonder there’s been an explosion of content pertaining to multiverses, portals, and time travel—taking us beyond beginnings, middles, and crucially, endings?

*

In 2016, I began doing research for an art installation based on the concept of “going viral.” I had no idea what shape the artwork would take, but I knew I wanted to dismantle the viral metaphor from all possible angles, including the biological. I found a free Virology 101 course offered online, which was genuinely delightful because the professor’s extreme enthusiasm for viruses was, well, contagious. In one lecture, he introduced a time-lapse of a viral infection with the description: “The greatest movie ever made.”

This loop of infection left a welt across my mind, though the planned installation never materialized. As I fell harder and deeper into the rabbit hole of research, it very slowly became apparent that I wasn’t collecting information to create art pieces, but to write a book, and that I was writing it because my parents died of a virus. I knew this was true because my visual sensibility, normally overactive, went dark. Not a single image presented itself to me. I had no choice but to turn to words.

*

Once I was able to admit to myself that I was writing a book, I came across an interview with Anthony Vaccarello, published about a year into his tenure as creative director for YSL. He reminisced about creating his first collection for the house, which involved visiting the Fondation Pierre Bergé Yves Saint Laurent for research. While there, one particular dress, “a fall/winter 81–82 black gigot-sleeved velvet number with a heart-shaped décolletage and a taffeta pouf skirt,” captured his attention. The obvious choice for his debut would be to update the dress in accordance with contemporary trends and build a set of looks around it, but Vaccarello “didn’t want to just take it and cut it like a mini-dress.” He “wanted to play with the collection as a collage, taking one sleeve from that dress, playing with leather...” I read these words and shivered: Could I do the same thing with a block of text—or an idea? Could I break it into pieces, a sleeve here, a neckline here, and grow a body around it? The article did not contain a picture of the inspirational dress, and its effect on me has been so profound that I’ve been afraid to seek it out.

*

The Observable Universe is ultimately about metaphor, and it employs several metaphors in a weird shell game to repeatedly demonstrate linguistic gaps between thoughts and feelings. I am fascinated by metaphor because it requires an act of conjuration, of producing an idea from a void. Lee Miller’s Portrait of Space (1937) perfectly conveys this. It is one of the first photographs I had a proper visceral reaction to in a museum: I stopped breathing—not for very long—but for long enough to think, “Did a photograph just take my breath away?” The work itself is deceptively simple, not much more than a segment of desert captured through a tear in a window’s tent screen, but from this collision a portrait emerges—one of space, no less. In fact, the true subject of the photo is the frame and its power to generate something out of nothing, like a metaphor. Without the screen’s tear and the other rectangles present within the image (which serve as additional frames), space would remain absorbed in the panorama of life, and completely invisible to the naked eye.

*

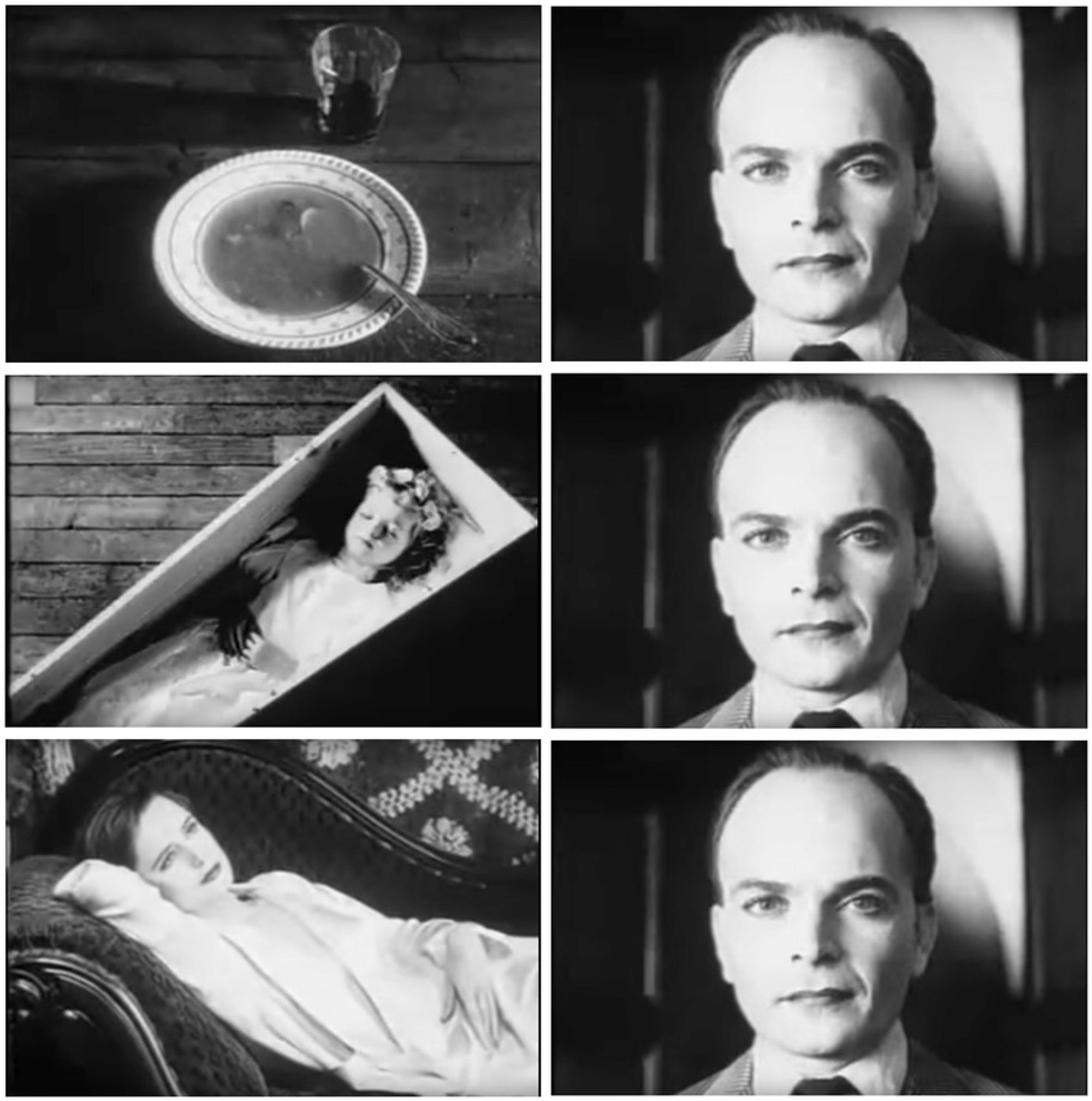

The structure of the book is loosely influenced by a Soviet montage technique known as the Kuleshov effect. Similar to metaphor, the effect works by refracting an idea into existence through the juxtaposition of images. Often these images are unrelated to each other, as in Eisenstein’s film Strike (1925), which features a sequence of factory workers on revolt interspersed with the graphic slaughter of a cow.

The effect was discovered in 1919 by Lev Kuleshov, the newly appointed director of the National Film School in Moscow, and his students, when they intercut a test shoot of matinee idol Ivan Mozzhukhin with images of a bowl of soup, a young girl in a coffin, and a reclining woman.

The Kuleshov Effect, 1919.

Despite the neutrality of Mozzhukhin’s expression, audiences were convinced these montages portrayed scenes of hunger, grief, and lust. From this, Kuleshov and his cohort determined that the actual power of cinema was in the organization of shots, or the editing, more than even the content.

I had written over 300 pieces of text for The Observable Universe but had no idea how to jigsaw them together. I could viscerally feel they were all connected, but I was unable to see the arrangement. However, something about the propulsion and intuitive logic of montage kept coming to mind, so I started to imagine I was editing a film. Applying the Kuleshov effect to the text allowed me to create unarticulated streams of content simply through the arrangement of information. It was another way for me to “write” about heartache and grief without explicitly engaging with those discourses. The feelings were not on the page, but in the cut.

*

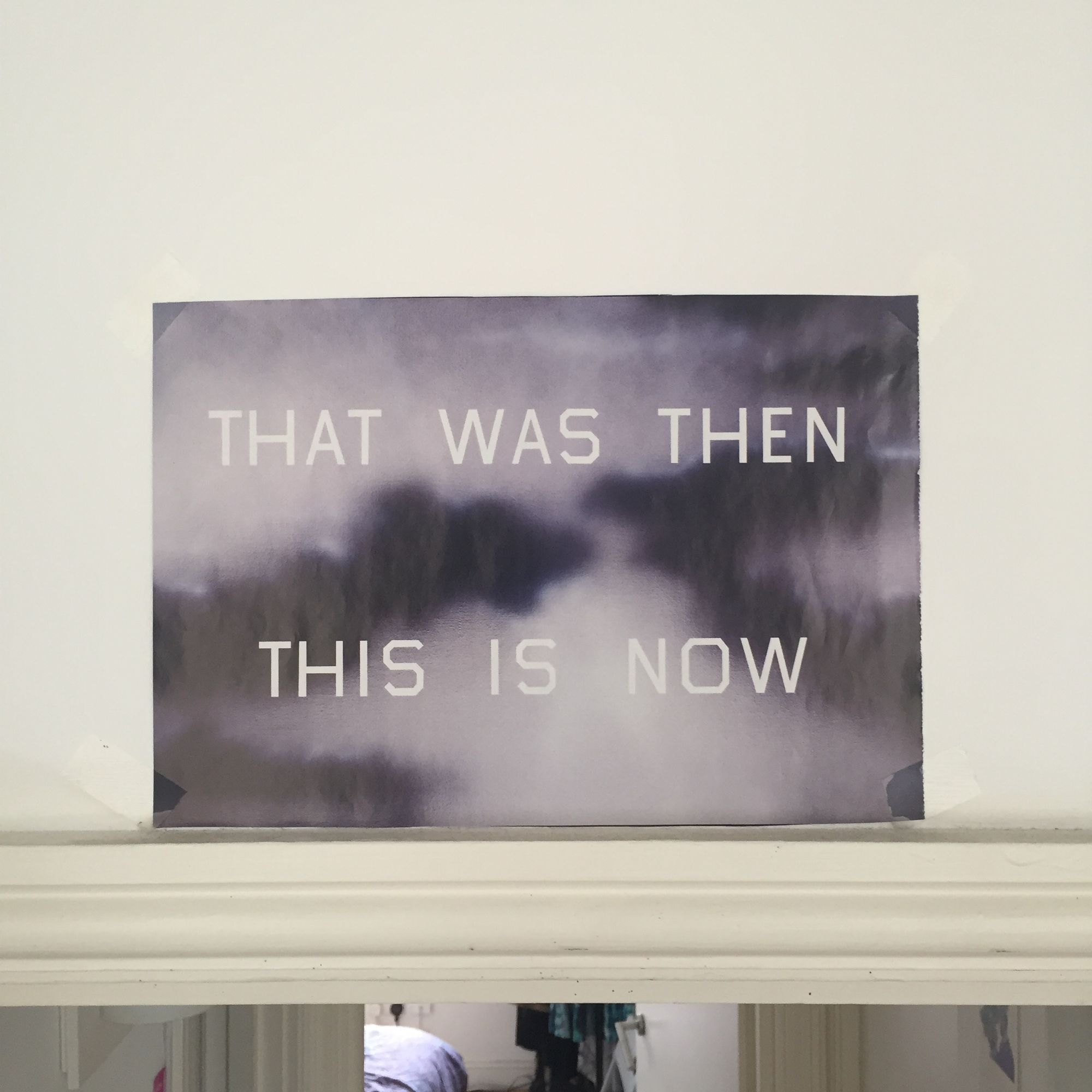

On a sharp day full of ice rain, I stumbled into the modern wing of the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. In a small room with pale walls, I found the accordion of Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip spread inside a glass case. For a moment I caught the sunshine and car exhaust and felt at peace. Shortly after this encounter, I found a full-page image of his work That Was Then, This Is Now in an issue of Artforum. Straightforward, the phrase of the title appears in white lettering over ominous storm clouds. While seemingly digestible in a single glance, internalizing the text is, to borrow from T. S. Eliot, an “occupation for the saint.” I tore the page out of the magazine and taped it above my living room doorway, so I would have to face it multiple times a day, every day, while writing about the past.

Ed Ruscha's That Was Then This Is Now II, pasted over the author's doorway.

Courtesy of Heather McCalden.According to the Sotheby’s webpage for That Was Then, This Is Now, Ruscha lifted the phrase from the title of a 1985 Emilio Estevez film, which is itself is an adaptation of a coming-of-age novel by S. E. Hinton. This movement of content—from book to screen to paint to magazine—is, to my mind, emblematic of the creative freedom of Los Angeles, the city where I grew up: Everything is there, in the light, floating around the smog and the infinity pools.

*

The freeways of Los Angeles lace the city together, and driving over (and under) some of the giant interchanges can feel almost like a divine hallucination. The engineering is so extreme that the typical response is one of marvel: How the fuck could anyone build anything so absurd? Solely functional in purpose, utilitarian in aesthetic, these structures nevertheless have a way of embedding themselves into you. In a certain light, these roads appear as the underlying foundation of the city’s psyche. When writing about networks and the Internet, I’d Google images of the Judge Harry Pregerson Interchange, and the Eugene A. Obregon Memorial Interchange, and study them like mandalas.

The Eugene A. Obregon Memorial Interchange in Los Angeles, California.

Photo: Peter Andrew LusztykThe Judge Harry Pregerson Interchange in Los Angeles, California.

Photo: Rémi Jouan*

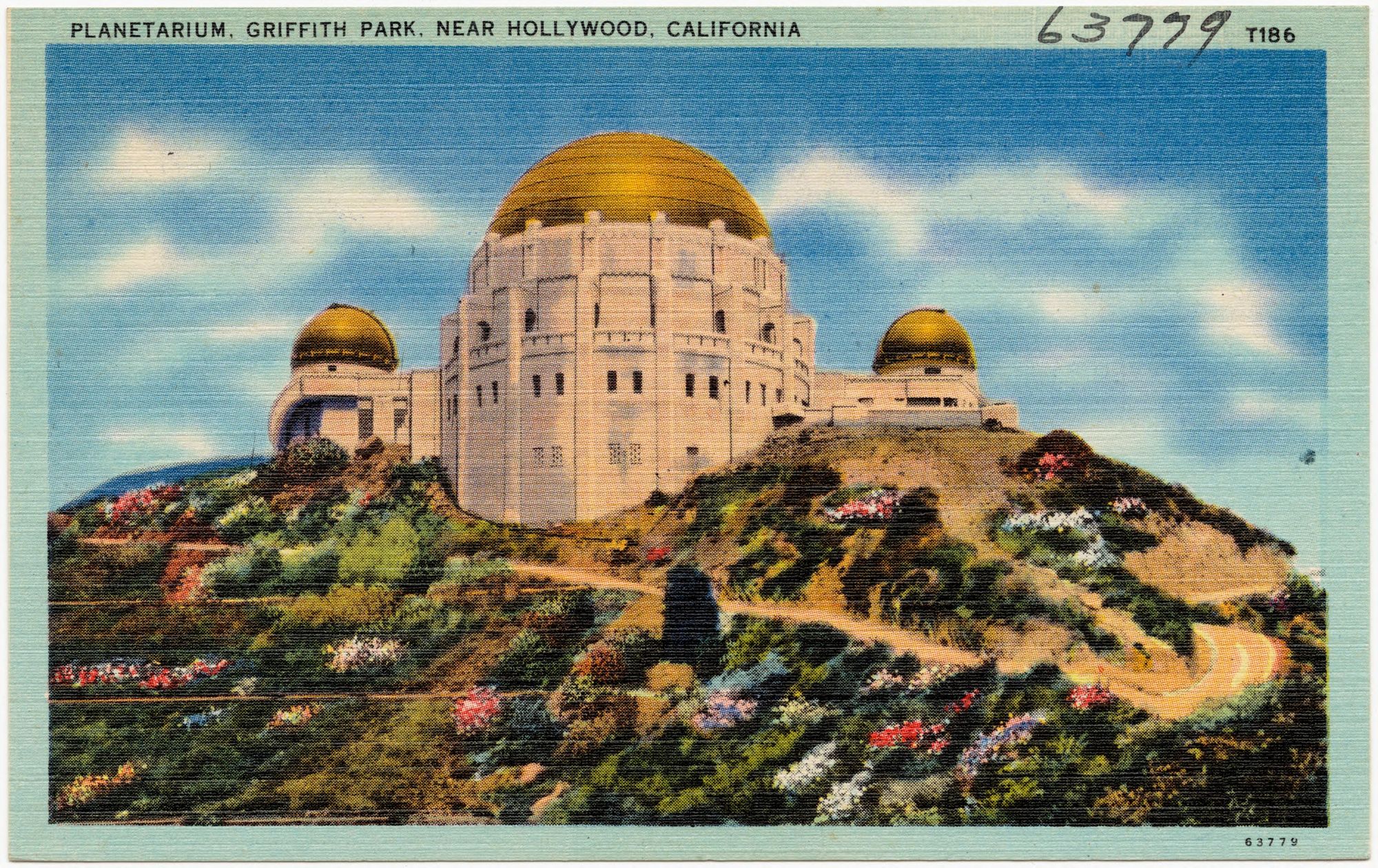

I had a postcard of the Griffith Park Planetarium above my writing desk in London because I wanted it to connect me to Los Angeles, where I no longer lived. I would fall into this image—which was an illustration and not a photograph—and let my mind wander. I have a deep fascination with postcards as a form of communication; sending the “scenic view” of a holiday destination to a person (you love) back home is a unique type of transmission. It is a picture broken off from its referent and sent hurtling across the globe, making it a literal moving image.

When I find used postcards at flea markets, I am often crushed to the point of tears by the simplicity of their messages. I can’t really explain it, but it feels related to how immaterial our communications have become—in both form and content. To write a postcard, you must hold someone in your thoughts, and the act of holding someone in your thoughts, no matter the duration, is a great and beautiful thing. Especially now.

Postcard from Griffith Park.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library*

A great love of mine is noir, in all forms. It is a genre of loose ends and smoke rings: No one finds the falcon in The Maltese Falcon, Sunset Boulevard is narrated by a dead man floating face down in a swimming pool, and The Big Sleep is famously impenetrable. Rarely, if ever, do the plots of these texts add up to anything. There is no redemption, no resolution, only the feeling of life.

My work owes a great deal to Raymond Chandler, but also to the film The Third Man (1949), one of the most perfect examples of cinema to date. Not only does it seamlessly capture the complete chaos of post-war Europe in under 90 seconds, but it also scrapes away at human relations with a charm so deceptive it isn’t until you leave the theater (or exit the streaming window) that you realize you’ve been mortally shredded. It is my favorite film noir, though it swaps out the hardboiled detective for “a scribbler with too much drink in him.”

Joseph Cotten in The Third Man, 1948.

Courtesy of Alamy*

There is nothing like the feeling of loneliness in LA. It is a brutalizing force that can very easily lead to madness if not counterbalanced by some ember of grace that, more often than not, is found in the changing spectrum of sunlight. As a rule, it is never to be found in other people, though the city is full of them, which is what makes the lack of connection so intolerable.

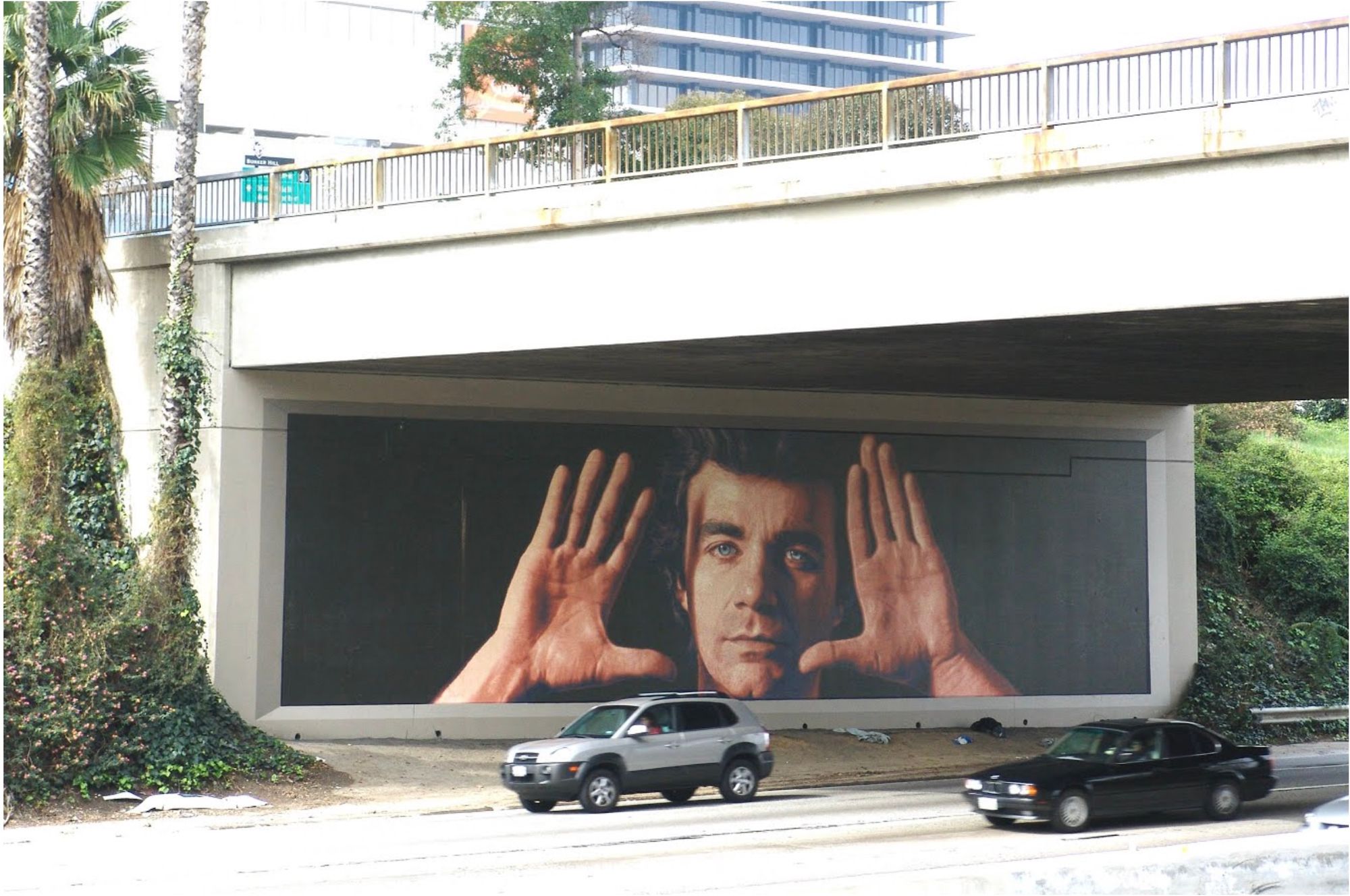

A duet of photorealistic murals that lined the 110 freeway pictured this feeling for me. From the early ’80s to the early ’00s, two faces rendered by the phenomenal artist Kent Twitchell tried to see each other across eight lanes of traffic and a cement pylon. On the northbound side of the 110, beneath the 7th Street overpass, a woman’s face stared out from between her hands—her palms out, open, and spread, as if up against a sheet of glass.

Kent Twitchell, 7th Street Altarpiece, Hollywood Freeway (101), Los Angeles, California.

Directly across from her was a man performing the same gesture.

Kent Twitchell, 7th Street Altarpiece, Hollywood Freeway (101), Los Angeles, California.

They were always connected but doomed never to meet—at least this is how my teenage brain understood the murals upon first seeing them. The whole situation of traffic, architecture, grime, graffiti, longing, sight, all felt symbolic to the place I was growing up in. What else to do but leave?

The murals were commissioned, along with nine others, in 1983 as part of the Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival. They were intended to convey the same sense of gravitas as the statutes that once lined the road to the original stadium in Greece. This brief was very liberally interpreted to create artwork on LA’s most highly visible and trafficked walls, which happened to belong to the freeways.

Twitchell titled his work 7th Street Altarpiece with the intention of creating a welcoming gateway in the heart of downtown. It turns out the faces, belonging to artists Lita Albuquerque and Jim Morphesis, were looking out at the commuters the whole time, not striving to reach each other. The other thing about loneliness? It makes you the fool.

*

In the film Another Earth, people submit essays to win an all-expenses paid trip to a duplicate Earth that has mysteriously appeared in our solar system. Over a montage that shows the protagonist’s solitary, daily life as a high school janitor, we hear her submission:

When early explorers first set out west across the Atlantic, most people thought the world was flat. Most people thought if you sailed far enough west, you would drop off a plane into nothing. These vessels sailing out into the unknown: they weren't carrying noblemen or aristocrats, artists, merchants. They were crewed by people living on the edge of life, the madmen, orphans, ex-convicts, outcasts... like myself. As a felon, I'm an unlikely candidate for most things. But perhaps not for this.

Ever since seeing this film, I haven’t been able to get these words out of my mind. It was the first time I had encountered something on screen that so openly acknowledged the radical value of being on the periphery, of being an outcast (or, in my case, an orphan).

All the works of art and literature that have transformed my thinking were made by freaks, sorcerers, or hermits—by people who didn’t belong. The act of creation, particularly with words, requires such a colossal leap of faith that the only ones truly capable of it are those “on the edge of life.” They are the only ones with enough courage—and sometimes recklessness—to pioneer into the dark, where, quite often, the future is located.

*

On days when the uncertainty of writing a book overwhelmed me, I’d just think of Peggy Olsen from Mad Men waltzing out of the offices of Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce, with a cigarette hanging out of her mouth and a painting of an octopus fellating a woman under her arm.

*

Hovering in the background of season four of Halt and Catch Fire is a video game called Pilgrim. The show is set in the early ’90s, and Pilgrim is an analogue to the real-life game Myst, a first-person quest through fantastical environments. Over the course of five episodes, the same fragment of Pilgrim cycles over various computer screens as characters attempt to conquer a particularly trying level. The viewer sees the pilgrim, an enigmatic, warrior-like figure, walk through a field, towards a floating ensō puzzle. The assumption is solving this puzzle will advance the player forward, and yet, no matter how it is solved, the player is always deposited back to the edge of the field. Unsurprisingly, Pilgrim is deemed pretentious, navel-gazing bullshit.

Pilgrim video game from Halt and Catch Fire, AMC, 2014. Film still.

The 8-bit landscape of the game is austere and Crayola bright, and its visual presence in the show registers as a strange horizon line, silently linking scenes and themes across episodes—until it fully erupts into the plot during a montage set to P. J. Harvey’s “Rid of Me.” In this sequence, a main character discovers that the pilgrim can travel on the Y-axis and into other worlds. Harvey’s screams punctuating the pilgrim’s ascent into the sky creates a revelatory sensation: You can only play this game by abandoning gravity, through a paradigm shift.

The idea of a video game exposing how presumption leads to failure is so wild and so unexpected that even though this whole subplot constitutes only three percent of the narrative, the moment is gasp-inducing. Players kept flaming out because they doubled down on logic instead of considering poetry.

Pilgrim video game from Halt and Catch Fire, AMC, 2014. Film still.

The best artworks force us to confront the mechanics of our own thinking. They go beyond providing content or perspective, and guide us to the actual structures that shape our thoughts. Once this becomes visible, observable, these structures can be consciously reengineered. As a consequence, your whole life can change.

∞

A photo of my mother and someone I do not know. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast