13 Ways of Looking: James Hannaham

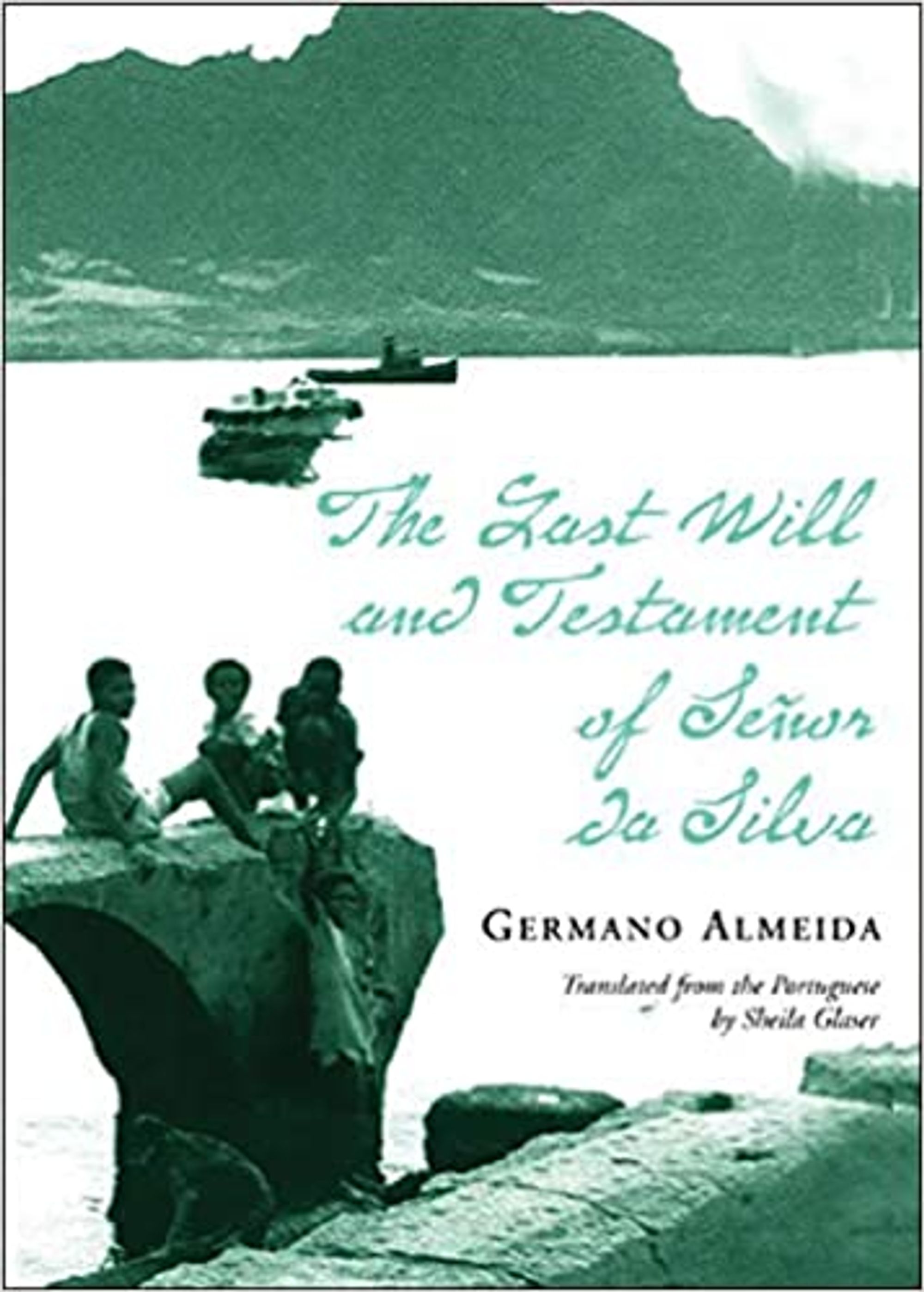

I should probably start by mentioning that we had just been to Africa. My father went there a lot; he was always trying and failing to start some international business there. Anywhere. At one point he tried to sell metal coffins in Ghana, then sawdust briquettes in Senegal or Côte d’Ivoire, and he brought back a lot of wooden statues of giraffes and other animals. He made these trips sound truly exciting. On one occasion, he got stuck in Gambia during a coup and had to sneak out on a boat at night. I always wanted to go with him, but he never took me or either of my siblings to Africa. Not sure why not. He died in 2013. When I finally got the opportunity to go myself, in 2016, my husband and I chose Cabo Verde. I am a fan of its biggest recording artist, Cesária Évora. It’s not particularly anti-LGBT, not too hard to get to, not at war—“one of the most developed and democratic countries in Africa,” says Wikipedia. An archipelago with an unusual postcolonial perspective. Uninhabited before European settlement, possibly because of its vulnerability to decade-long droughts, it essentially owes its existence to the slave trade. Whenever I go to a new place, I bring a representative book. In this case, it was Germano Almeida’s brief and funny The Last Will and Testament of Senhor da Silva Araújo.

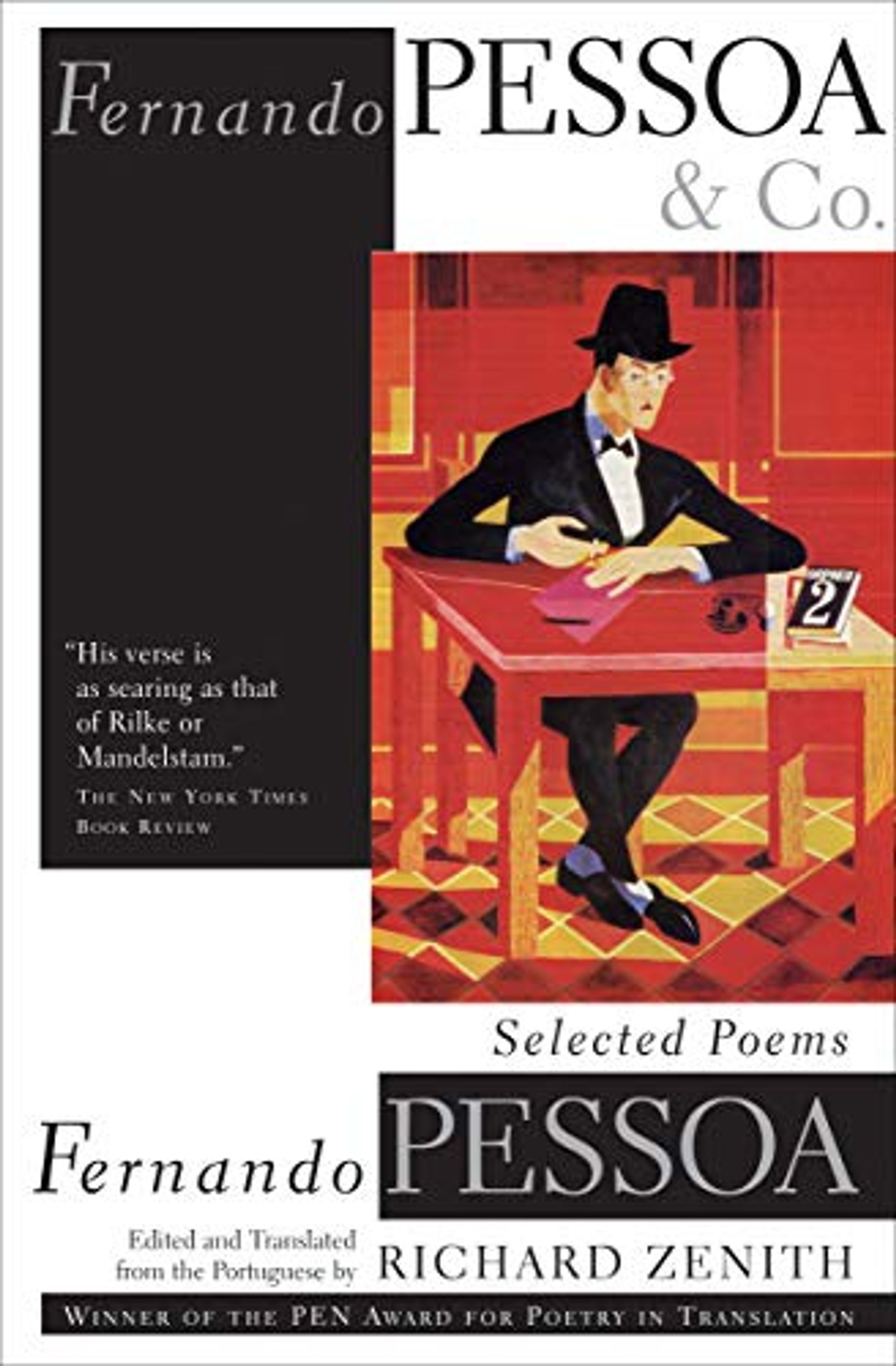

Getting to Cabo Verde often requires a layover in Portugal, its former colonial overlord, and we decided to spend a few days there on the way back, mostly in Lisbon. I’d brought another book—Fernando Pessoa & Co., an anthology of work by Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. Early in the twentieth Century, Pessoa created nearly eighty alter egos, writers he called “heteronyms,” who had their own styles, histories, and relationships, which is a very late twentieth Century idea. Fragmented selves, self-reinvention, etc. Also, Pessoa left almost all of his work unpublished in a trunk in his Lisbon apartment after he died. Once his oeuvre became known, it seemed ahead of its time.

I had finished The Last Will and Testament of Senhor da Silva before we left Cabo Verde, so I opened Pessoa & Co. as we flew from Praia to Lisbon. I was conscious of this itinerary as a historic trade route, as always disturbed by the precarity of air travel because of my obsession with Air Disasters, a TV procedural about aviation mishaps, and on top of that, it was December of 2016. A month before, He Who Will Not Be Named had just been elected President of You Know Where. Additional maniacs ruled other countries. So when I opened the book and read the line, “I’ve never kept sheep / But it’s as if I did,” attributed to the Pessoa heteronym Alberto Caeiro, it set fire to a host of associations and questions already piled up in my mind. An imaginary person had just claimed that his lack of expertise was equivalent to real experience. That sounded familiar. What if the pilot of the plane had done the same? I don’t have the data here, but it seems as if when unqualified people become leaders, more people die needlessly than usual. Pessoa invented Caeiro as a poet of the non-poetic, a Chance the Gardener type who sees profundity in surfaces—“…things are really what they seem to be / And there’s nothing to understand,” he writes in a later section of “The Keeper of Sheep.” This could be the rhetoric of an autocrat, I thought. What is it doing in a book of poems? I decided that I should make a project of responding to this work even before I got off the plane. Eventually I titled the book Pilot Impostor. How could someone fake the highly specialized knowledge and real experience necessary to be an aviator? How could a scam artist convince people that the plane was actually in the air? We would soon find out.

The moment we arrived in Lisbon, things felt strange. This doll lay on the baggage claim conveyor belt, eternally circling. Had she fallen out of a suitcase? Who had lost her? Rough treatment for another lonely, unreal personage.

The next event I can’t represent except with this stock image of the Lisbon Airport’s car rental area. I can’t locate any record of which agency we went to. But when we got there, the woman behind the counter had on a nameplate that read Pessoa. I stared at it for a while, figuring Pessoa was the Jones or Smith of Portugal, and then mustered the courage to ask her if it was a common name. “No, it isn’t,” she said flatly. I took the opportunity to mention the book. Maybe she was his grand niece or some other distant relative? Pessoa had no descendants. “I don’t know if I’m related to him,” she said, “But I love his work.” I have never had, before or since, a discussion about poetry with a car rental agent. I’m sure many are capable. It just doesn’t come up often.

If you’re already aware of Pessoa and his image—Peter Sellers comes to mind again—you will see him all over Lisbon, like a game of Where’s Waldo Pessoa. If you aren’t looking, you probably won’t notice him at all. In December, Lisbon felt oddly empty. The Christmas decorations were minimal compared to other places we’d traveled during the holiday season. Even southern Vietnam had more extravagant Christmas flare. Also, we didn’t see any evidence of the recent economic downturn. It seemed as if people had decided to carry on buying high end consumer goods and services without acknowledging any inability to pay for them. No part of town seemed poor, or even sketchy. We visited the cliffy beach towns on the coast almost every day; they were deserted.

Maybe thinking of Caeiro’s obsession with surfaces, I immediately noticed that streets and walls in Portugal have an unusually wide variety of textures. What’s more, there are a lot of squares. The streets are paved with millions of little square stones. Many of the walls are decorated with square ceramic tiles. I started taking photographs of every new surface I encountered. I was already thinking that I would design the book as I wrote it for some reason. That didn’t work out, but I ended up using pages of the early drafts with the words removed as images in the book. Without looking it up, if you don’t already know, how old do you think Lisbon is?

The walled town of Óbidos, an hour or so north of Lisbon, has some walls, arches, and windows painted a distinctive shade of blue, an intense, luminous azure known locally as Azulejos. To me it looked a little like Yves Klein blue. Some of the wall tiles are fired in a similar hue. There are often many layers behind all of these surfaces, ones Caeiro might not acknowledge, due to the many different empires that have dominated the Iberian Peninsula.

When I returned home, I made a practice of responding to each of the poems in Pessoa & Co. on a semi-regular basis. I would read one, think about it for a while, and then decide how I wanted to answer it without regard to genre or form, as a way of referring to Pessoa’s work without imitating it. I have delved into many types of writing over the years—criticism, fiction, arts journalism, experimental plays, fake wall text, advertorial—so though I usually use my own name, I have been my own heteronyms and created an occasional alter ego. Somewhere along the line, the questions about identity and airmanship I’d had at the start of the project transformed themselves into a more unresolved existential conundrum, that one where each of us is the inexperienced pilot of our own consciousness, possibly real, possibly unreal, careening toward inevitable disaster. But you know, having a lot of fun along the way. And gaining real experience.

Lisbon is 3,221 years old. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast