On Unlearning Conceptions Around Disability

I first learned about Taeyoon through his visual artwork—which often features abstract human figures and other whimsical characters rendered in bright, painterly colors—and later got to know him quite well as a collaborator, friend, and thought leader in the creative tech space. A gentle soul and a co-founder of the School for Poetic Computation in New York City, Taeyoon has a refreshing way of looking at technology as a tool for practicing care. In his work, he explores science, technology, society, and relationships through computer programming, drawing, and writing—often with other artists, experts, and communities. Over the past few years, he’s been collaborating closely with various disability communities, and through this work, he’s learned a lot about how arts and culture organizations can do a better job welcoming people with disabilities into their spaces and programming.

Today, in partnership with Pioneer Works, Taeyoon published A Guide for Co-Creating Access & Inclusion on The Creative Independent which articulates some best practices for access and inclusion that he’s learned from disability communities over the years. Recently, we got together over Zoom—while it was 8pm my time in New York, and 9am the next day for him in Seoul, South Korea—to unpack a few of the key ideas he references in his guide. As we spoke, a few people trickled into his studio space for a new day at work, and the sun moved gently around the room.

Please note that this interview is intended to be read in tandem with Taeyoon’s guide, as many of the topics covered here are elaborated on in more detail there.

Hi! Are you at your house in South Korea?

Mm-hmm, I’m at my family’s house, where I live and work now. It's a hanok, a traditional wooden house. There's a garden where I'm sprouting some vegetables and herbs in the back. I have a little pond where I’m raising moss.

How do you plant moss? I thought it took years to grow.

I didn’t plant it, I collected it from the creeks in the mountain. It's a very unique hobby, raising moss. Some of them are resilient to different weather, and some can actually survive freezing over the winter. I'm also interested in lichen, which is an organism that is a symbiosis of a fungus and algae—so it's a living and nonliving collaboration.

Raising moss and lichen sounds like a good way to work with a slower timescale. How has it been living in South Korea? I know you relocated from New York City mid-pandemic to be near your family.

Moving at a slower pace and finding space has been a real benefit of getting out of New York City. I now split time between here in Seoul, and then up in the Gyeryong mountain, where my dad has a little farm. Out in the mountains, I help take care of old trees. Have you heard about yew trees? They’re kind of like a pine tree. It's a delicate wood that medieval people used to make bows and arrows.

I love having the ability to connect with nature here. When I was living in New York, I loved going upstate, doing outdoor work, and spending time outside of the city whenever I could. I was always thinking about what a community practice could look like outside of a dense urban area.

As an artist, I used to travel so much before the pandemic. I was going to the airport every week for talks and research trips. That was not sustainable for a lot of reasons. I was always dropping in and out, so it always felt a little transient and alienating. I tried to avoid the tokenization that can come from having brief encounters with a community by doing multi-year projects in different cities, and building relationships over time. But even then it was hard. Going to art festivals one after another feels like going to a different person’s wedding every weekend.

Image from Taeyoon's exhibition at CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile) in Hong Kong.

Image courtesy CHAT.

Image from Taeyoon's exhibition at CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile) in Hong Kong.

Image courtesy CHAT.

Image from Taeyoon's exhibition at CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile) in Hong Kong.

Image courtesy CHAT.

Image from Taeyoon's exhibition at CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile) in Hong Kong.

Image courtesy CHAT.Right, where you're just constantly making small talk with new people and never getting to a deeper level with anyone.

Yeah. And since the impact of artists is often measured by how many workshops and talks you do, or how much reach you have, the idea of “succeeding” can become very quantitative. I was living in that system for a long time.

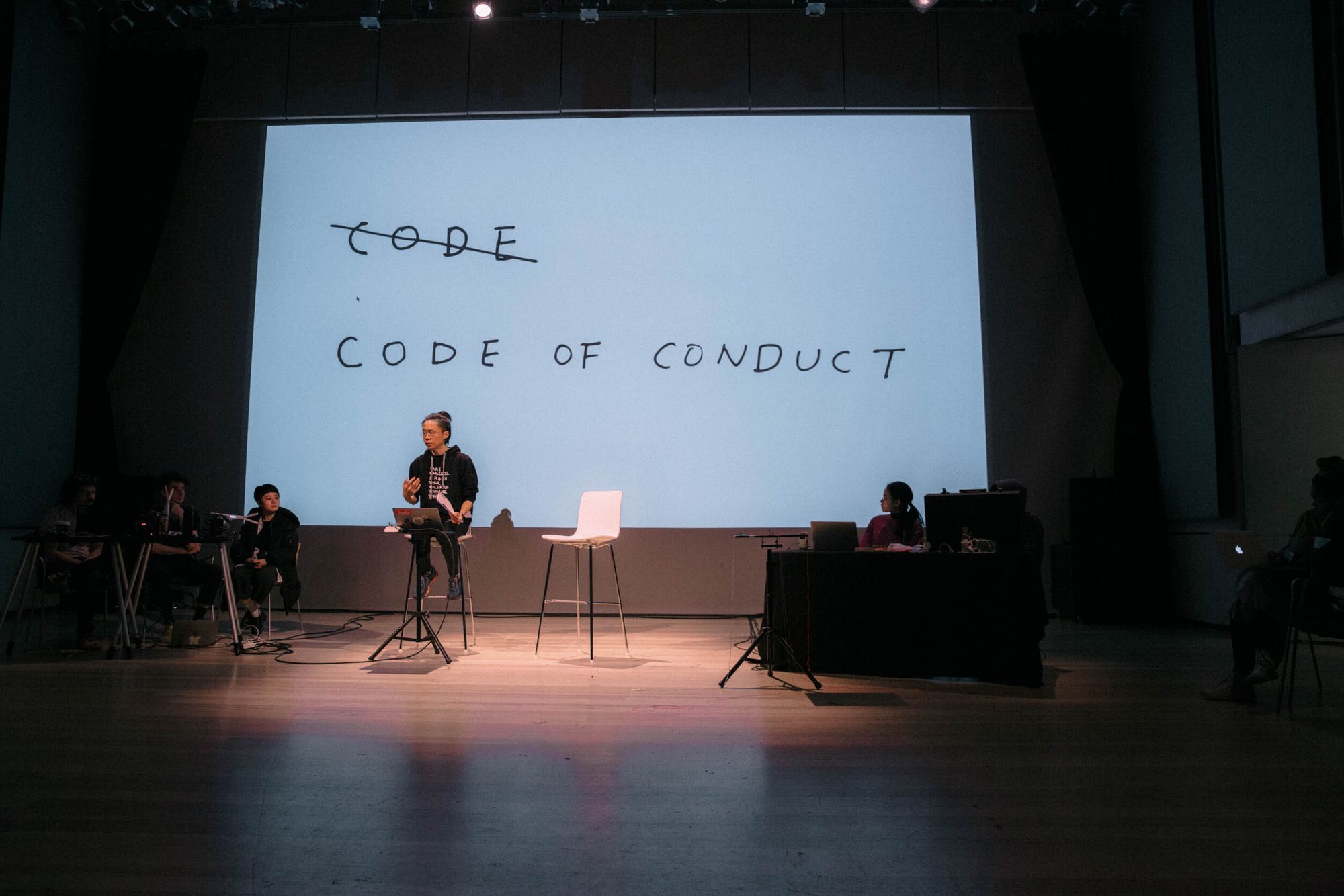

A lot of challenging things have happened since the pandemic for me and for my community at large. In the Spring of 2021, I stepped down from the leadership of the School for Poetic Computation for a new generation who could create a safer space for marginalized students and staff. They updated the school’s mission and code of conduct, and are already organizing new classes. I’m thankful and excited for their future.

Moving to South Korea has also brought surprising changes: I'm now focusing very locally, and also working with communities outside of America and Europe. Being in South Korea has helped me connect with Southeast and Central Asian communities. I’m also now working with people in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. They are doing amazing work in post-Soviet states, and we are talking about issues related to activism, technology, and the environment.

If I stayed in the US, I don’t think I would have had the chance to connect with these groups, or the opportunity to look at the West from the outside. It's very odd to see my American friends fully vaccinated and partying when only 11% of South Korea is vaccinated, for example.

I assume you’re not traveling, and that you're connecting with these communities online?

Right, I'm not traveling. We are doing remote online summer school. It's called the Summer School of Unlearning, made up of four different nodes in Korea, Japan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. All of us teachers are alternative educators or artists, and the communities are diverse. The Kazakhstan node is called Art Collider, and they're an active and young organization, very feminist and spirited. They focus on socially engaged arts and free education in a city called Almaty. It's the second-largest city in Kazakhstan.

In Kyrgyzstan, we are working with ArtEast, a slightly older generation of artist-activists who work with nontraditional artists. There is very little infrastructure for arts and culture in these places, so they have to make everything on their own. There are traditional art schools, but the training is still similar to the Soviet days—like realistic paintings, and sculptures of muscular bodies and such.

Approaches to art education in Korea and Japan are surprisingly similar. We don't have the same Soviet ideology, but we still teach rendering, drafting, and sculpting as if it's 1910. So in the School of Unlearning, we talk about how traditional education shapes our ideologies, and how it's important to break away from that.

That's a good segue to bring up the guide you just published on The Creative Independent, which is all about how organizations can welcome the disability community into their spaces, events, and programs. I know the guide grew out of collaborative research around “unlearning disability,” which you led a workshop on at Pioneer Works a few years ago. It seems like that's a similar kind of conversation to ones you have now with your students, focused on unearthing and unlearning harmful associations and preconceptions.

Yes. Before I continue, it's quite important to say that I am not disabled but I collaborate with disabled artists and friends. But I did not always have the language or framework to really understand their disability or the kind of discrimination that they experience. Many people who are not disabled feel like, "Oh, I have nothing to say about this, I have no experience." I try to challenge them about that.

A big part of “unlearning disability” is to unpack the concept—how it's a construct that's determined by the external environment and how it's a personal lived experience. When teaching workshops and organizing exhibitions—such as Poetic Coding with the students of Ebenezer School and Home for the Visually Impaired, Unlearning Disability with participants at Pioneer Works, Distributed Web of Care with Jerron Herman and students of the School for Poetic Computation, and Interweaving Poetic Code at Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile—I usually expand on the notion of disability as an identity, culture, art form, and expressive element. I introduce some of the artists, scholars, and activists who, first and most importantly, take pride in their disabilities, and, second, create work that is reflective of their experience. I’ve referenced many of them in the guide, but to share a few here, they include Sins Invalid, Mia Mingus, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, and the Disability Justice collective.

That's an important point that you bring up, that those who don’t identify as disabled may not engage because they don’t think they have anything to contribute or that these issues aren’t relevant to them. How can that assumption be reframed?

Most people don't feel comfortable talking, or asking questions, about experiences outside of their own. There’s a fear of sounding naïve, making a mistake, or being misunderstood. Because of that, they don't want to say anything, which often leads to disengagement and leads to more isolation.

We need to get over these fears and unlearn the binary distinction between “able-bodied person” and “disabled person” because the concept of disability is always shifting. Some people are born with disabilities, others develop them as they live and age, but almost everyone will experience some kind of impairment at some point in their life. So it's a shared human condition, not something that keeps us separate.

Taking all that into consideration, how did you approach writing your guide to access and inclusion?

The guide is a result of the last five years of collaborating with different disability communities—the suggestions come directly from them. It's also a way to bring together important theories and approaches, such as co-creating a community code of conduct and making online programs more accessible by writing Alt-Text captions for images. More than a be-all, end-all guide, it's more of a primer for people like me to begin making programs and spaces more accessible.

At the beginning, it was hard for me to talk about these things because I felt like I didn’t know enough, but I’ve found that people are more disheartened by apathy and unwillingness to learn. We make mistakes, we are naïve, and we, of course, don't always understand the perspective of other people who live differently than us. But that fear shouldn't stop us from engaging with a topic.

On your website you write, "We are at the dawn of change, with the opportunity to embrace a new notion of accessibility, diversity, ability, and inclusive learning." There are a lot of possibilities right now—coming from new technologies, yes, but also from this kind of awakened state where people are more aware of these types of conversations. In your opinion, how can we best position ourselves to unlearn disability right now?

I think celebrating unique lived experiences is the first step. As one example, there's a person named Sky Cubacub, who uses the collective name of Rebirth Garments, based in Chicago. They create custom clothing for queer disabled people, and these clothes are fantastic in how they celebrate each person’s unique body, needs, and imagination. When I encountered their practice, I felt like, "Wow, this is amazing," because it's about celebrating each person as they are.

I do think technologies are improving disabled people's lives by providing communication tools and access. Many of my Deaf friends say that smartphones have changed their lives for the better, because they can tap a message onto the device and show it to other people. People see smartphones all the time, so that's totally understandable to them. All that is great. I do have a problem with narratives in which technology will solve social and cultural problems, though. Often, tech solutionism places technology before humans, and can flatten the wide range of disabled experience. There's this TED-conference-oriented culture in America of focusing on individuals who are beautiful—not just physically beautiful, but also polished in how they craft their identity and narrative. It can make people feel incomplete or inferior.

That's the whole idea of capitalism, when you get down to it, right? Teaching people that they're not good enough the way they are. Everyone is so conditioned to strive for a largely unattainable ideal, rather than accepting their own inherent humanness, whatever that looks like. Why do you think ableist culture is so baked into our society?

That's an important and difficult conversation that we may need another few hours to get into. Many of my disabled friends research, write, and make art about that. Christine Sun Kim makes work that engages with the historical medicalization of Deafness that isolated Deaf people from mainstream society. And Sara Hendren's book, What Can a Body Do, talks about how our concept of disability is shaped by the ways the built environment is designed for certain bodies over others. And there are so many more that I mention in the guide—the disability justice field is very active these days.

Are there any main takeaways you hope readers will come away with from the guide?

The guide is geared towards art workers who want to work with disabled people and maybe haven’t yet. I hope it encourages and supports them to ask the disabled people in their community what they want, as a way to start. I also hope it reminds people how important it is to prioritize access and inclusion, versus thinking of it as just an add-on. Even if your budget is limited, there are plenty of DIY, grassroots methods to make your programs more accessible.

Mainly, I hope the guide will help readers to proactively think about these topics, and to feel okay with possibly making mistakes along the way. I felt like I was probably making some mistakes while writing it, but it’s worth it to say, “Hey, let's give it a try, see what feedback we get, and then build from there.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast