The New Woman Behind the Camera: Visions, Studies, Self-Portraits

The New Woman Behind the Camera, on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 3rd, presents a wide-ranging survey of photographs taken by women between the 1920s and the 1950s. The exhibit, conceived by Andrea Nelson for the National Gallery of Art, brings together two hundred images, spanning studio portraits, street photography, photojournalism, fashion and advertising, ethnography, and avant-garde experiments. Together, this body of work suggests an alliance between the modernizing camera and emerging forms of self-definition among a global class of women. My response to the exhibit after seeing it this summer was roving, associative—a series of self-portraits that invoke my own memories, obsessions, and desire.

Our mom, who is lying on a bed or a couch, has been diagnosed with Virginia Woolf syndrome. It’s my impulse to explain this disorder to my family. “Well, it’s mainly about patriarchy,” I say. Our mom is wearing the costume of a bird. A Woolf in bird’s clothing, I tell my sister. What kind of bird? she wants to know. Like a heron? “Blue,” I say. “Or indigo or violet. With a long, pointed beak—is that a raptor?” The beak frames our mom’s face when she speaks, as though her mouth is eating her face. “That’s certainly an image,” says my sister. We wonder will she be medicated? And what sort of drug will cure the disease? “Besides lesbianism,” my sister says, and we laugh, because how does terror lead to love? Lately her dreams have been troubling, too.

When I was young, I used to perform little dramas in front of my bedroom mirror. In one, I was a teacher with the answer key, and one was maybe about refugees. The Holocaust came into it somehow. I found a striped fabric remnant in my mom’s sewing supplies and draped it over my shoulders like a shawl. Holocaust cosplay offered a high-stakes drama onto which I could project my own anxieties, attendant on school cafeterias and Bible quiz bowls and authoritarian dads (my own dad and dads in general), plus I was a middle child. There was a fear of being seen, fear of not being seen, fear of getting out of line or getting it wrong (as in: raptors do not have long beaks). Fear of eating, of playing the piano, of praying or not praying to the God who hovered just over my bed, watching with a dad’s grim forbearance. What was I doing in front of the mirror but looking for a way out of that room?

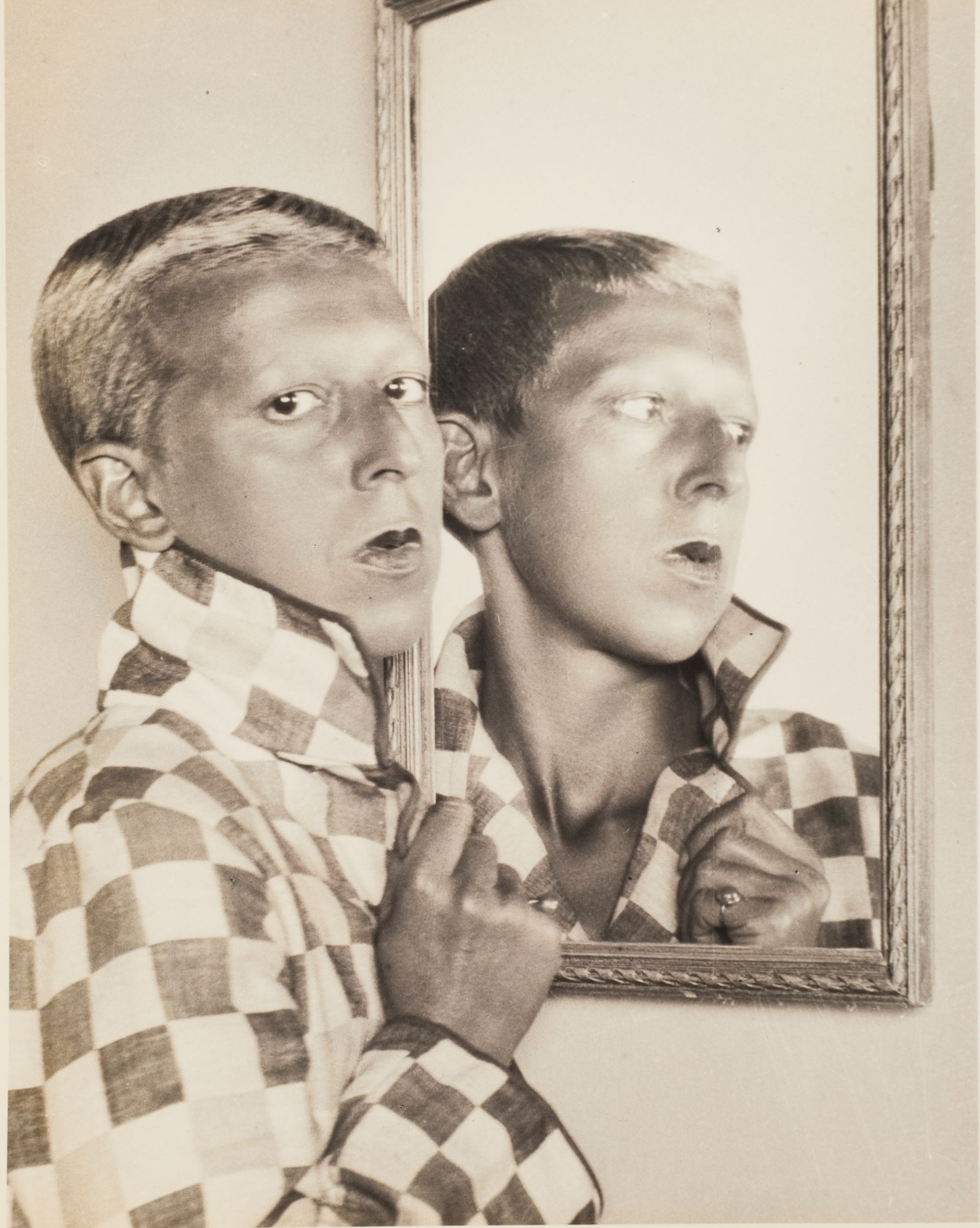

So here’s Claude Cahun, which sounds like the name of a busker, a gambler, a circus performer, or thief, like a character in a folk ballad or a detective series, where false names multiply, alter egos abound, and the mirror reveals some hidden knowledge. I recognize the figure or figures in this portrait, or I think I do or I want to use the image as a mirror, because it thrills me. It’s the bright, shorn hair, the popped collar, the way she grips her lapel, her mouth, a tantalizing bud that won’t open, not for you. It’s her self-possession and the way the self somehow also slips past her as she turns her head to gaze at the camera. It’s the look of someone who likes tricks, games, deceptions, provocations—a cut-up artist, a taunter of Nazis, a manly woman or womanly man, it depends on the Cloaked in a checkered harlequin coat, she insists on hiding something from view, while her double in the mirror reveals the curve of a jaw, the long line of a neck, and the deep cleft between collarbones, which invites our desire—though the gaze goes somewhere we can’t follow. In the close-cropped image, these two faces—coming and going—preside like Janus at the gate.

Every JCPenney studio portrait is the same: sisters assembled in a suburban mall on wooden blocks of varying heights, hair combed and curled, feathered or clipped. Before us, someone stands a few feet from the camera, clicker in-hand—Look here—so that in each image, we gaze into the near distance, while behind us the backdrop looms like violent weather. We all wear maroon and pink one year. Or navy blue and forest green. Jewel tones, floral prints, solids, stripes, plaids, and here a pair of collars that look like doilies. It’s as if we’re attending a costume party where the theme is Whiteness or a Dateline special on missing children. Or an episode of Before They Were Queer, suggests my sister. “Even the way I wear that dress in the bottom one,” she says. “Very gay.” The portrait’s rigid determinism—the uniform gaze, the regime of coordinating colors, the standardization of family life and identity—is undermined by a stray detail, a rogue little lick on the drumhead, like the length of my sister’s sleeves in one or the crooked path of her bowl cut. Subtext surfaces from the murky backdrop, the way I’m sort of slouching in this one, sinking into myself, while my neck strains upward, away from my body, as if trying to leave it behind.

In the house next door, there are two boys—the one who’s older and his friend. At school, the boys are either buzz cut little Air Jordan stormtroopers or they’re outsiders, like the geologist’s son, with his gold-rimmed glasses and white-flecked collar or the kid whose favorite t-shirt says WHERE'S THE BEEF. The stormtroopers say things in the lunch line, they want a reaction, they look for a weakness, they knuckle your skull, and so the worst thing is to draw their attention. Better to stay out of it, whatever it is. I don’t know the boys in the house next door. I have no reason to remember them, really, except for the day that I’m telling you about, because not long after this, the family moves out and another family, the Foddrills, moves in. But this afternoon, the one I’m telling you about, the older boy and his friend are crouched on the roof of the house next door. They’re looking down through the window of the bedroom where I’m performing for the mirror. I’m wearing the striped shawl and my mom’s sensible heels and blue plastic sunglasses with the lenses punched out. I hold a three-ring binder in the crook of my arm, the way Miss Martinson does, because beyond this narrow, rose-papered room, authority belongs to dads and elementary school teachers. I hear the boys’ laughter before I see them. They’re out there looking down on me. I could wave at them or stick out my tongue or flash them or flip them off—fuck you, stormtroopers! If they are stormtroopers, I’m not sure. Who wouldn’t want to change their seat in the bleachers, when nothing changes, ever, around here, but the slow movement of seasons—football, basketball, baseball—over the mown fields? And what will happen when they leave, dropping onto the driveway, slamming the screen door behind them, while I wait, flattened against the wall, unmoving, out of sight?

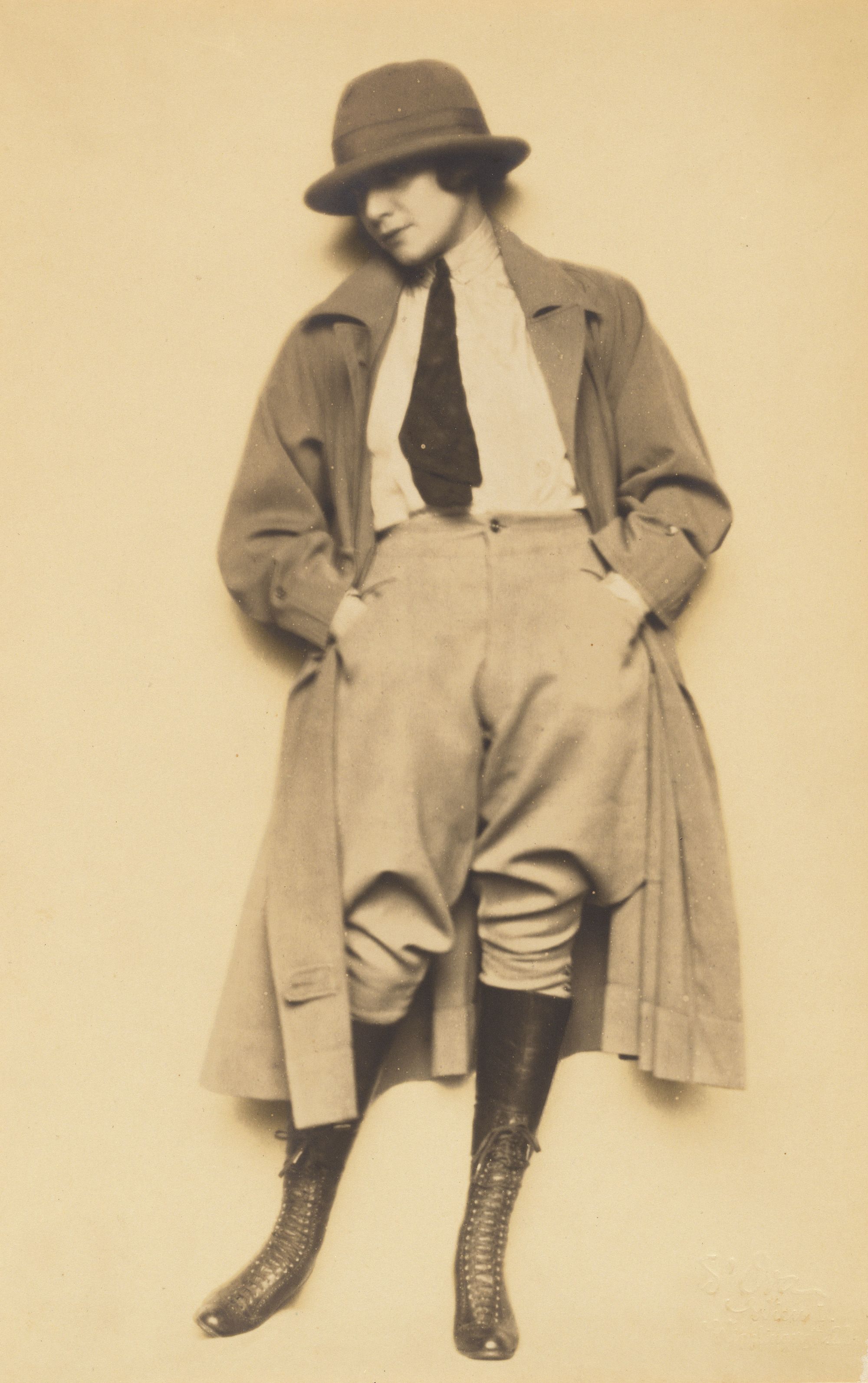

Hilda and Mary, mother and daughter, liked to stage these scenes at home. Here, they’re dressed as Jacob and Esau. The Old Testament story, as I recall, involves a hoax: one brother disguises himself as the other brother to trick their father into blessing him. (As always, the blessing involves the distribution of power.) In the Gospel stories, it’s often easy to identify the villain or hero—Doubting Thomas, Mary Magdalene, Judas, and others whose names signal virtue or guilt. But it’s hard to know what to make of Jacob the trickster—Jacob, playing dirty, who comes out on top. Think of the intimacy kindled by taking the form of another, when you put on his clothes and/or the skin of a goat because your brother has hairy arms. You step inside the dim tent where your father is dying, bringing a little meat and your brother’s scent. You offer your father a hand, a kiss, which is your brother’s hand, his kiss. What does Jacob learn of Esau, I wonder, by playing his part? The biblical text doesn’t say—and anyway, that’s not really the point. The point of the story is power: who has it, who wants it, and how to get it. In the story, Jacob’s mother Rebekah helps him. Actually, the whole thing is her idea. She cooks up the elaborate scheme, from concept to costume design. Maybe she knows that if you want to trade places with somebody else or grasp the heel of power, you have to study the role.

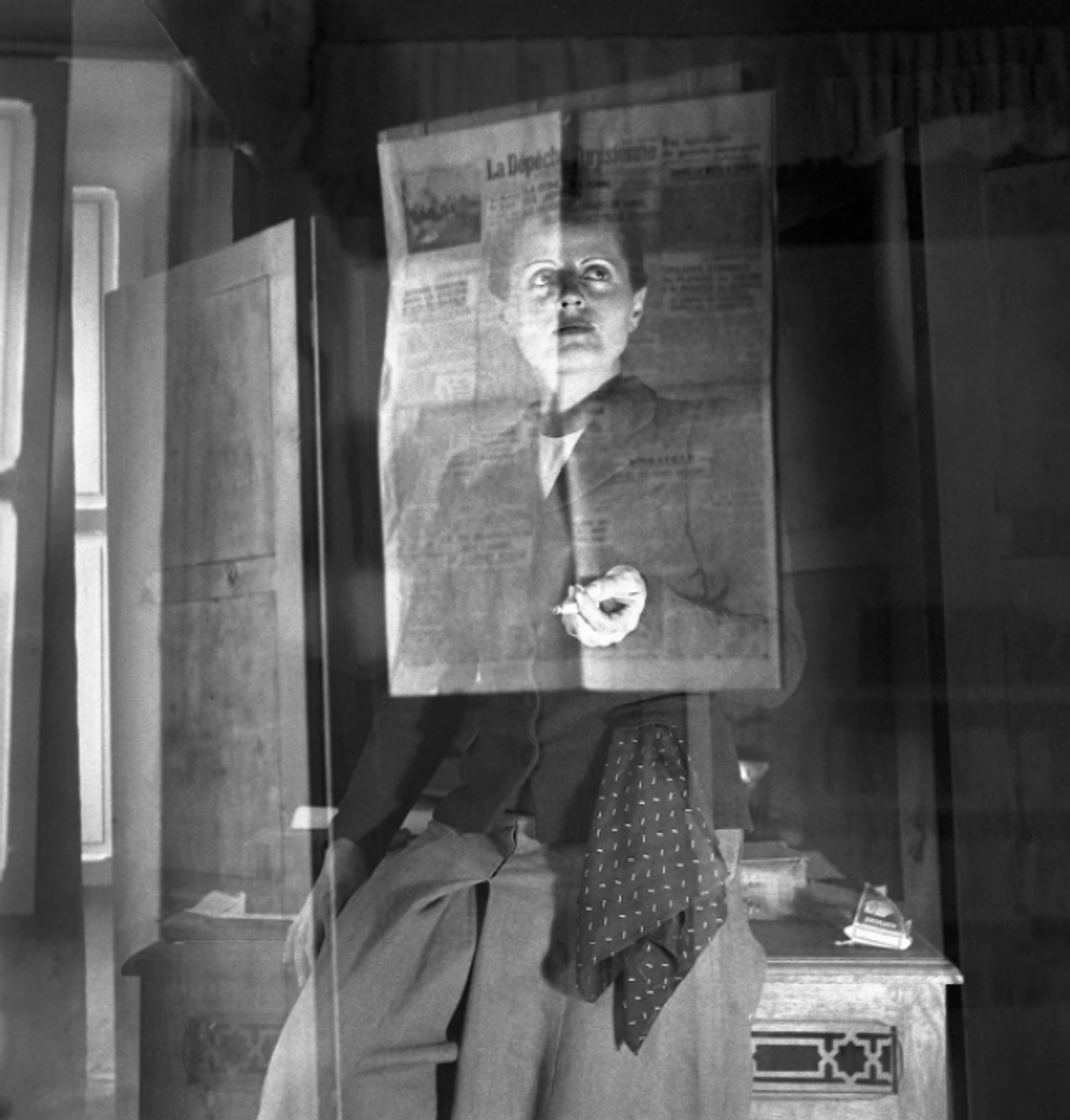

One day she appears on the front page—now she’s news, she’s new. She’s buttoning her jacket and a pair of pants, as if readying herself to enter the chamber of a dying man to pull the old switcheroo. Maybe she cuts her hair. (I remember the beauty school where our mom would take us for discount rates, the plastic cape cinching my throat and someone aiming a pair of scissors: “She’d be pretty even without her hair.”) Without her hair, she’s what? Her hair is her security blanket, someone said to me the other day, running her hand over the dark, wavering surface of her head, while the other women reassured me that they liked my short look, they just wished they had the courage for it. If only they had the right face! I smiled, shrugged, said sort of briskly, “Well, there are no rules.” But of course there are rules. Think of the unsettling case of Mary Babnik Brown. The woman gave her hair to the war effort—thirty-four inches, never colored or cut or corrupted by the heat of a curling iron, offered to the Allies for building technologies of war. The state wanted virgin hair. It wanted blonde hair, following the dominant logic of value within American mass culture. After surrendering her locks, I read, Mary Babnik Brown of Pueblo, Colorado, cried for two months. But what does the blonde woman’s hair secure? What fantasies does it preserve or sustain? “Our dominant story of beauty is that it is simultaneously a blessing, of genetics or gods, and a site of conversion,” writes Tressie McMillan Cottom, uncovering the tensions in white feminine beauty. “You can become beautiful if you accept the right prophets and their wisdoms with a side of products thrown in for good measure. Forget that these two ideas—unique blessing and earned reward—are antithetical to each Perhaps the new woman, like Jacob, has a taste for both blessing and conversion—sovereignty and freedom—and their spoils.

The souvenir sweatshirt is red and printed with the word GETTYSBURG. Its cuffs are worn, and there’s a small stain near the collar. She drapes the sweatshirt over her shoulders and knots the arms so that it hangs down her back like a cape. She stands, swaying, in the center of the room, wearing the sweatshirt as though gripped by a pair of arms or two hands clasped near her heart. When she starts to twirl, the sweatshirt makes a bright flourish around her. She wants to give me something too or she wants me to know the feeling of taking, which is not the same thing. Tell me what you would like, she says. I want you, I tell her, to give me something you want for yourself. I want to know how she likes it. She says, Not like you. She wants me to call her a lady, so I do. I want her to lead. She tells me a secret, then I tell one too. I’m not just trying to please her. I’m trying, I think, to become the kind of lady she is. But it’s not a question of trying. When I move my hand against her skirt, it’s effortless or it appears to be. I move softly along each ridge, and it’s like her body is mine. When she wraps her legs around my waist, I believe she wants to be flattened by tremendous force. I would have wanted this too, if I had faith, like the saints, in the application of pressure to treat a deep wound. Then we stand, and the woman adjusts her skirt and pulls the knotted arms of the sweatshirt around her. Am I even, she says, turning to face the mirror. Later, she doesn’t care about even. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast