The Eyes Go Out: The Photographs of Alan Kleinberg

I.

The first thing Alan Kleinberg showed me was the Marvin Israel book. As Alan told the story, Marvin came to dinner one night—this was years ago—and said, “Let me see some of those 35-mm pictures you’re doing.” He told Alan to bring him an empty book, and then he asked for some tape.

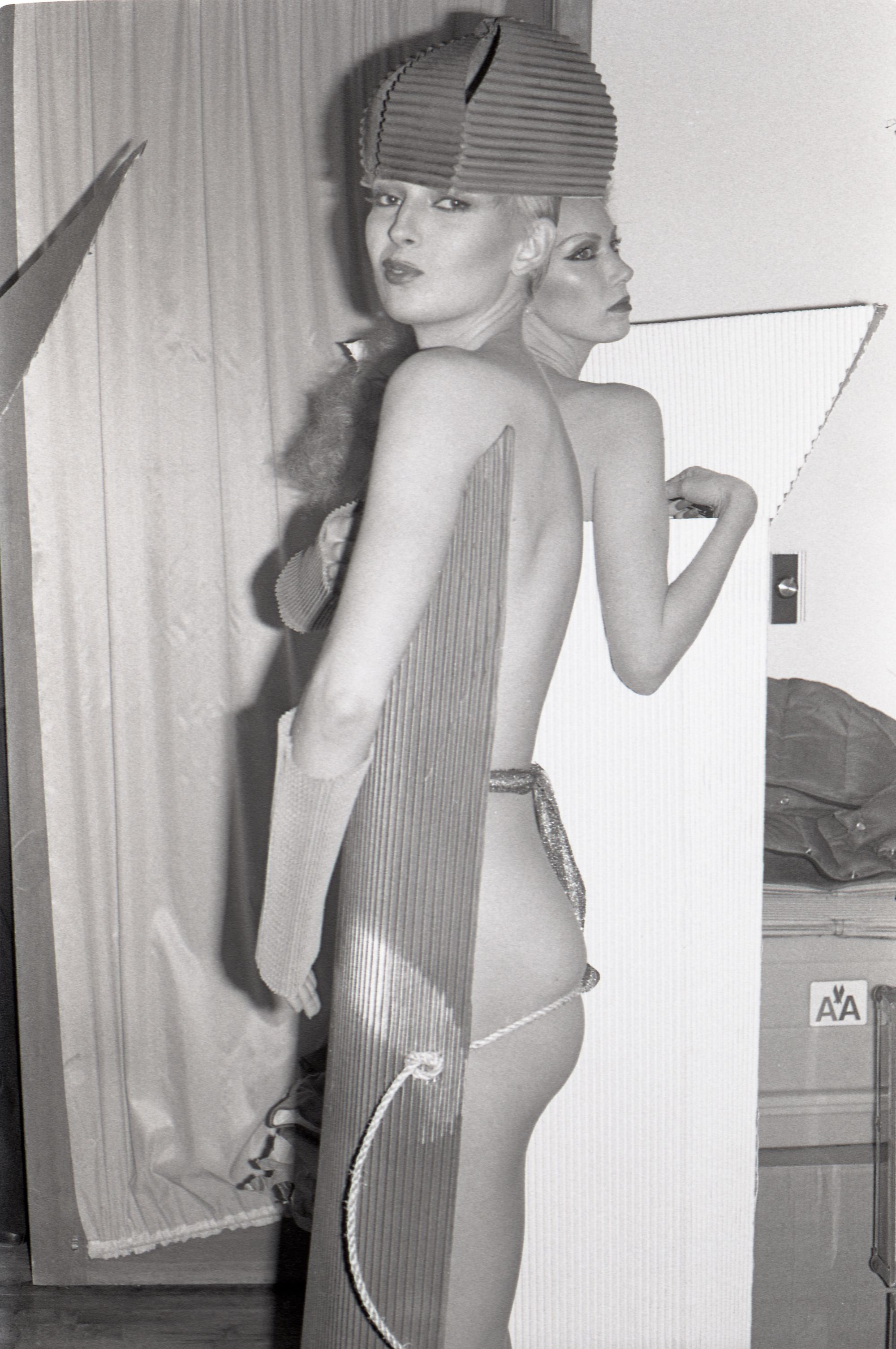

Marvin was one of those people who could just pull things out of a hat, according to Alan. An artist and influential art director, Marvin shaped the books and exhibitions of Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Peter Beard, and Lisette Model, among others. At Alan’s that night, he selected images and assembled the rough idea for a book, including portraits of characters from uptown and downtown: the Met’s legendary curator Henry Geldzehler, looking rakish in an ascot and smoking jacket; Halston’s lover Victor Hugo wearing leather and brandishing a hammer and sickle; Warhol in a quiet moment, napping in a chair at his home on Long Island. There were socialites, models, artists, transvestites, Vogue’s doyenne Diana Vreeland beaming like a blue ribbon winner. There were openings, parties, fundraisers, a wedding; all of it appears to be of a piece, animated by dancing, dress up, and the carnival art of trading places with somebody else.

The book was never published. Alan added to it over the years, elaborating its pages with commentary, clippings, and small mementos. Toward the end of his life, he kept the book in a black box, as if the object, like a sacrament or religious text, contained the revelation of a great mystery.

What the book reveals, in part, is the artist’s ad hoc methods of construction, his eye for the odd or amusing detail. These traits perhaps reflect the irreverent, DIY spirit of the 1970s—but something else, too, appears in its pages.

On the flyleaf is a postcard image of the Holy Infant overlaid with a packaging label: “Unexposed Ilford Film.” On the facing page is a note written by Alan in pencil: “This book was an experiment for preparation of a book design prepared by Marvin Israel in 1980.” The epigraph, like that word unexposed, signals the provisional status of the object. Here was an artist who was always making a beginning—or never quite finishing what he started. He had an amateur’s zeal and an affinity for the inconclusive or indeterminate.

What he liked about photography was that there are no rules. By turns a hairdresser, a fashion photographer, a producer of music videos and films, Alan was also an obsessive chronicler of the scene around him. “It’s like I knew there was something that I had to pay attention to,” he told me. Even when he was young, he was always watching what was around him. He joked that it’s because he was so short. People were sometimes put out, he suggested, by what must have seemed like an errant attention. “You know what’s wrong with you?” a friend said once. “All you do is look with your eyes.” But his gaze wasn’t that of the dilettante, exactly, but the outsider’s—someone looking for a place to belong.

II.

When I first met Alan 2014, in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, he had the mild euphoria of a man in the passenger seat of a car with all the windows down. He was unguarded and reflective. “I guess people are what I’ve photographed most,” he told me. “They’re what I know least about and have the hardest time getting close to.”

He lived alone in an apartment overlooking Gramercy Park. The place was filled with books on photography, insects, birds, the temples of Pagan, the Japanese art of tsutsumi, and other enthusiasms. There were Noguchi lamps, I remember, and empty bird cages. The coffee table was propped up with a stack of 2-¼ negatives. He kept a framed pair of tickets to Woodstock and the erotic mounds of a woman’s ass, which was chiefly horticultural, he told me—the seed pod of a coco de mer from the Seychelles.

He was seventy-one, spirited, and eager for his debut exhibition at a storefront gallery in Bushwick. I was helping edit the catalogue. The curator, John Silvis, was a friend of mine, and he introduced me to Alan.

We talked about Marvin and others he knew—“the greats, the near-greats, and the ingrates.” He told me about Southern Boulevard in the Bronx, where he grew up; his mother, who watched Billy Graham and read Langston Hughes; and his father, a nightclub comedian, who taught Alan there’s a thing called show business: you do whatever you want until you get a kick in the ass.

We used to stroll through Gramercy Park or head into the Flatiron District where Alan could peer into windows and faces. He liked the way certain people walked. “This one looks like a dancer,” he’d say. He recorded his impressions at shutter speed, though by that time, he no longer carried a camera.

He was starting to lose his mind—or his mind, as he put it, was losing him. It was like a wave that came out of nowhere, he told me, trying to describe the sensation of Alzheimer’s disease. It was like electricity. Like a crackling sound. It was like being asleep with a train going by. It was like a theater and something was going on, but then he didn't know what it was. Like suddenly it just went out.

But his photographs had an unerring acuity. They disclosed a series of scenes—at the Mudd Club, the St. Regis, Castelli Gallery, the downtown bar they called One U—whose grammar and meaning I wanted to learn.

“Oh, you’re so pure!” he said to me once. “That’s because you’re from Iowa. You aren’t sure whether to step your feet into the big lushy New York City.” I wasn’t pure, and I’d been in New York for years, but I still couldn’t figure myself into its places, it’s passages and doorways, among the people who made it mean anything. Maybe I thought if I studied an earlier time and place, I would know how to live in my own.

III.

The Marvin book opens with a photograph dated 1975 and captioned Eclipse—a party. The black and white image frames a portion of a ceiling where a balloon has drifted alongside a bare light bulb. The two figures—bulb and balloon—make a kind of visual pun, one shape echoing the other. With the partygoers outside the frame, the image introduces us to the one with the camera, alert in the moment just before an eclipse, when one bright body comes alongside another and hovers overhead.

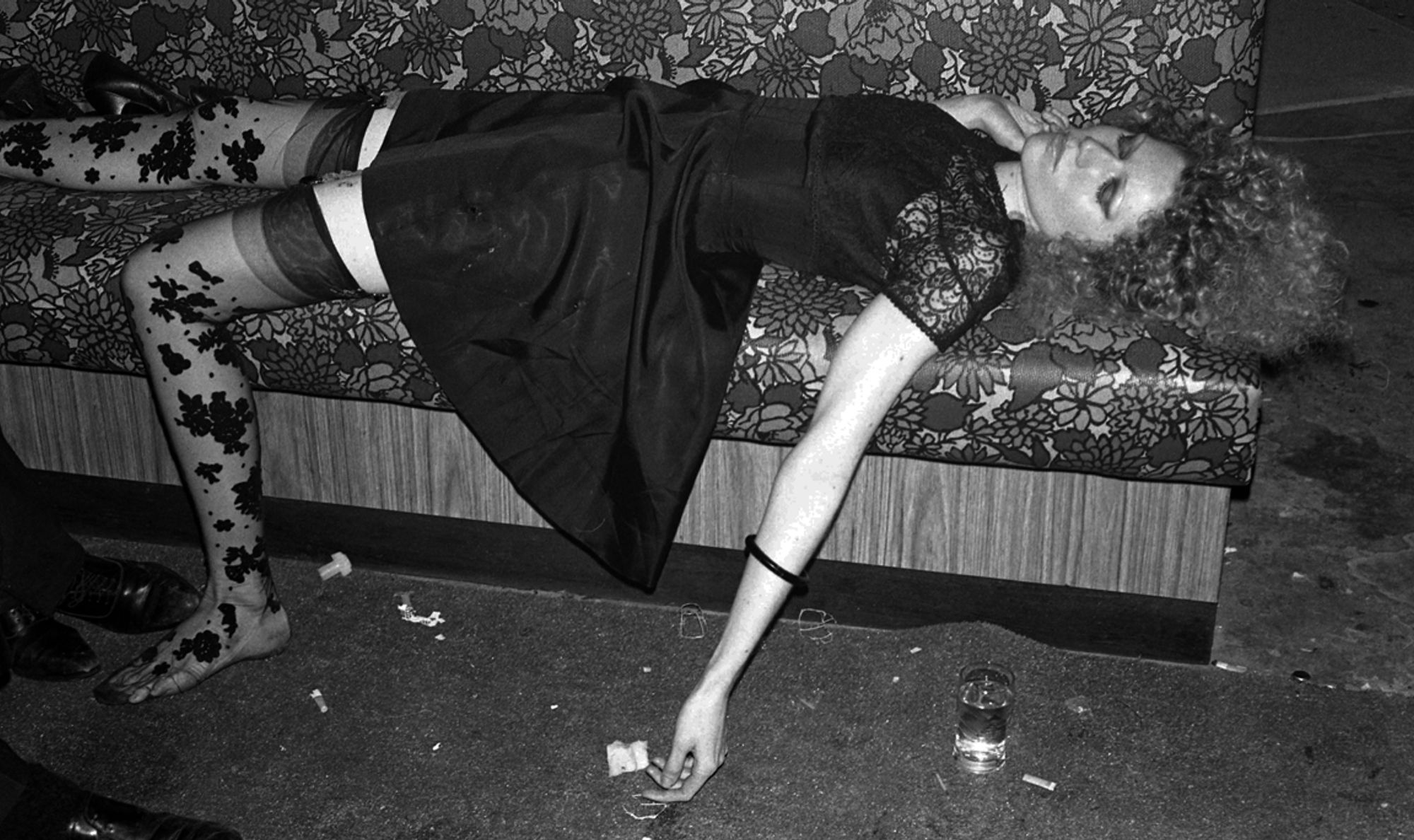

Picture him, lean as a jockey, moving up Madison Avenue or down into SoHo, a Leica in his hands. On the street, he saw how a person holds himself or clutches at her companion or handbag or parcel, trying to get a grip. He used his camera as though lifting his subjects from the flow of happenstance, accident, or the fatal slide to the curb. Take Bombed Blonde, Mudd Club, New York City, 1979, for instance, first exhibited in 2014 at OUTLET Fine Art. A woman wearing a black satin dress and black lace stockings lies on a couch at the Mudd Club. She’s flat-out, gone, one hand grazing the floor—the picture of abandon, though she isn’t alone. Someone else’s shoes appear at the bottom of the frame. On the floor, among cigarette butts and other debris, someone has placed a glass of water. You could almost miss this detail, but the photographer didn’t. It’s the outside chance, the door that leads to an elsewhere.

I’m thinking, too, of an image of Jacqueline Kennedy in 1977 at the International Center of Photography. It was the opening of Peter Beard’s exhibition The End of the Game, featuring blood-smeared photographs of elephants and rhinos. Kennedy is at the center of a crowd. The patterned spots of her dress suggest a creature caught by the pack. Three men press in on her in that way you might recognize, if you’re a woman. But Kennedy, composed, looks past the one who’s talking to her, baring his tongue and teeth. She lifts one arm across her body to smooth her hair, and it’s a small act of self-preservation—a line drawn between herself and the man. This is the camera’s saving grace: to notice the gesture just before the man’s jaw snaps shut.

IV.

Beside these scenes, I want to place an earlier series of snapshots—family album photos of Alan’s young wife. In some of them Shari is a Nancy Sinatra blonde; in others, she’s a brunette. (The New York Post, which ran only a photo of her jewelry after she died, described her as “a shapely and attractive ) In one undated photo, she wears a black bathing suit and reclines on a patio lounger. She wears the same bathing suit in another set of shots, where someone has printed on the back Cheri or Sheri—wife #1 or just #1.

Someone, probably Sontag, has observed that all photographs are forensic. If Alan’s club kids and street scenes have the immediacy of an unfolding drama, his pictures of Shari offer trace evidence of something after-the-fact. They perform the belated work of ID—recognition, rather than rescue.

Here, Shari appears on a beach, empty except for a loblolly pine in the background. Someone, maybe Shari, has written on the back of the photo in ballpoint cursive—Cheseapeke Bay—a single e out of place, like that tree, standing alone against a white sky.

“This was the great romance,” Alan once told me. “It was like that movie Love Story, the way that it boiled.”

What I know about Shari I’ve gathered from talking to Alan and digging through his archive. She came from California; she wanted to be an actress. She rented an apartment near Times Square and got a job at the Copacabana selling cigarettes and checking hats. In 1963, she met Alan at Orchard Beach, and they married the following year.

“It was like waking up into a dream,” Alan writes, staging the scene of their meeting in a typed short story or a treatment for a film, never made. She had bleached blonde hair and a black bathing suit. He’d never seen anyone like her. “They took to each other the way children do,” he writes, casting himself and Shari as young lovers in a summer melodrama.

In the story, Shari’s hypnotic effect mingled with the haze of heroin. They spent hours in bed together, eating spaghetti, drinking Champale, discussing witchcraft, astrology, magic, poetry, Edna St. Vincent Millay. Their beginning wasn’t a courtship, but an engagement, as Alan puts it. But they were so young—twenty, twenty-one. It couldn’t hold over time. Or maybe it could, if they were that kind of people, but they weren’t. He was the one who introduced her to dope, he recalls, contemplating the beginning of the end.

By the time Shari died in February 1966, she and Alan were separated. She was living on Christopher Street, and he had moved further uptown. He went to see her on weekends and brought her a little money and whatever else he could think of to make things easy for her. He didn’t know who she hung out with. He couldn’t tell me what she was doing that night in Flushing, Queens.

The newspapers called her the Mystery Death Girl or the Girl Found They called her the Girl in the White She was “heavily made up.” She was wearing “off-white corduroy slacks, a white and brown sweater-blouse, light tan car coat and white boots with fur tops,” according to the Daily News. She had $21 and three keys in her pockets when she was found in Queens in the rubble of an industrial

The police questioned Alan at the precinct. How long had they been separated? When was the last time he saw her? Did she work? Did she host loud and late parties? Which pills and did she ever mix them with booze? He saw her recently, he told the cops, and they discussed reconciliation, but came to no agreement.

Police also questioned Spyros Skouros, a friend of the family and chairman of 20th Century Fox. “She had talent,” Skouros told reporters. “And she was a very attractive girl, very well dressed, poised and pretty. She could have been a good But the problem was that she was “a fairly heavy Or the problem was that she had “numerous” Or maybe the problem was her ambition—she was “stage-struck,” according to The headlines and copy suggest a leering fascination with the figure of the dead white girl, her body pinned where it lay by the moralizing gaze of the beat cops and crime reporters. But what is the moral of the story?

He never learned how she died or even where. There were tire tracks in the empty lot, but no marks on her The mystery and trauma of her death—its essential privacy, followed by its public disclosure—perhaps sustained Alan’s relentless photographic looking.

V.

In the summer, we took the train to Amagansett, where Alan’s friend Susan Forristal had a cottage. She was a girl from Texas, full of life when they met in 1968. They went around the world together, according to Alan. (“I only lasted half the world,” Susan told me.) At the beach, the sea sloshed against the sand. Susan rubbed sunscreen on Alan’s back. “Isn't it nice that we got together?” he said. We greeted someone arriving with two dogs and a carload of boys. Susan admired the woman’s bathing suit and we all admired the boys—seventeen, eighteen, cartwheeling into the surf, climbing onto each other's shoulders, loose and kicking, handsome, and so polite. Standing in the wind at the edge of the surf, we watched the breakers come in. “It’s not summer if I can’t dive,” said Susan, so we grabbed hands, going rapidly into the water as the waves fell against the earth. In the evening, Susan cooked dinner while Alan played a song on the boombox—Elvis Presley’s “Long Black Limousine.” The song was about Shari, he said.

I felt I understood how Shari might remain fixed in his mind, as everything else ebbed. I’ve also lost a spouse. I know how an act of sudden undoing seems to go on and on, because sometimes in my dreams my husband is alive.

When Alan couldn’t live alone anymore, he moved into a studio in Susan’s building, then into her apartment, where, she told me, he used to sit on the edge of the bed, saying softly, “That poor girl.”

He was in a nursing home last year when he died of COVID-19. Earlier, Susan had gone to L.A. to look for a cemetery plot. At the Forest Lawn Cemetery in the Hollywood Hills, she found Shari’s unmarked grave. We wondered why Alan never put up a stone. We knew he visited the place. But a headstone is so final, I suggested. Whatever’s left undone leaves an opening for some other outcome.

But this is only how I see it. Alan would tell a different story.

Did he feel like a failure? Journal entries from the early 2000s reveal him worrying about money, anxious about his status, wrestling with anger. He could be volatile or withdrawn, his friends told me. For a while, he was knocked flat by depression. He was always plagued by self-doubt.

Among his things, I found a handwritten note, maybe twenty years old, from the photo editor at Men’s Journal: “Alan—Thanks. This is an eclectic mix. Some nice work but inconsistent and a bit of a mess. Some really wonderful photographs mixed in. D.”

Elsewhere, he kept this typed list under the cryptic heading “things said”:

“You are a layabout” Gordon Munro

“You don’t know how to think” Saul Leiter

“You have no ideas” Jerry Shore

But Alan also kept another document listing his influences and mentors. Giacometti appears here, as well as Sam Beckett and Irving Penn and “just about every other photograph I have met pro or amateur” [sic]. He credits Gordon Munro for his advice and the use of a dark room. Saul Leiter “somewhat pathetically taught light meter reading.” Art Kane “told me I could move forward, back, side-to-side.” From Sophie Calle, he learned “unpredictability,” from Louis Faurer, “compassion, and from Jean Pagliuso, “delicacy.” It’s an avid, loving (if eclectic) list.

VI.

In the hallway of his apartment in Gramercy, there was a large black and white print signed by Richard Avedon. In the picture, taken on the Caribbean island of Great Exuma in 1968, the model wears a black bathing suit. She’s stretched out on the sand, offering the smooth cavity of her ear like a mollusk to a stone-sized pearl. That was the season Mrs. Vreeland at Vogue tried putting pearls in the ears of her models. “Nothing ever came of it later,” Alan told me. “You wouldn’t see women in Bloomingdale’s wearing something like that.” Alan is the other one in the image, crouched beside the woman, as though he found her there asleep on the sand, as though schooled in the art of transformation, holding a hairdresser’s comb to her head.

The model is Lauren Hutton, but the photo makes me think of Shari in her black bathing suit or Antonioni’s Anna. L’Avventura was the first film he ever saw that really meant something to him, Alan told me. A friend from the old neighborhood in the Bronx took him to see it. There was a terrific boat, he remembered, but how the rest of it went, he couldn’t say.

Here’s how the rest of it goes in Antonioni’s film: two friends—a blonde and a brunette—board a yacht in the Aegean Sea. Ancient islands rise around them. Someone naps in the shade of an awning while the wake spills from the boat’s stern. The morning papers are tossed overboard.

“Islands, I don’t get them,” says the owner of the boat. “Surrounded by nothing but water. Poor things!”

These women were made for black-and-white: the blonde, the brunette, whose despair is perfect like the shape of an egg, her desire retracted behind her beauty where it may be hidden even from her.

They wear bathing caps and leap from the side of the boat. In the water, the one named Anna—the brunette—cries shark. Later, she confesses to her friend that she was lying. There was no shark. Then, maybe winnowed by the tide or caught in one of the coves, Anna goes missing. Her lover takes up with her friend, the blonde.

Together, they search for the missing woman, moving across the screen like crooks on the run. They’re too guilty to take comfort in one another, too expectant to grieve. What they’ve lost binds them together and keeps them apart. At last, the search trails off in a post-party dawn, when Anna’s friend finds her lover in the arms of another woman.

Is this a cautionary tale? Anna’s disappearance—and whatever else drops from view—reveals the pathways of loss, their hidden enjambment, like a line that stops and starts again along another route.

Subscribe to Broadcast