The Object Talk: Seth Price

When artists make good work (magic!) they’re often asked questions about their “process”—you know, reasons why they made the work, what they were thinking about, and what the work means to the community (market?), or some larger context beyond the gallery or museum. A month or so ago, I was sitting in my apartment on the sofa trying to give myself some purpose, something to do other than what I was supposed to be doing, when I woke up my computer and ordered Fuck Seth Price: A Novel by Seth Price. A friend had mentioned him for years—he’d come up in conversation from time to time—but I never dove in.

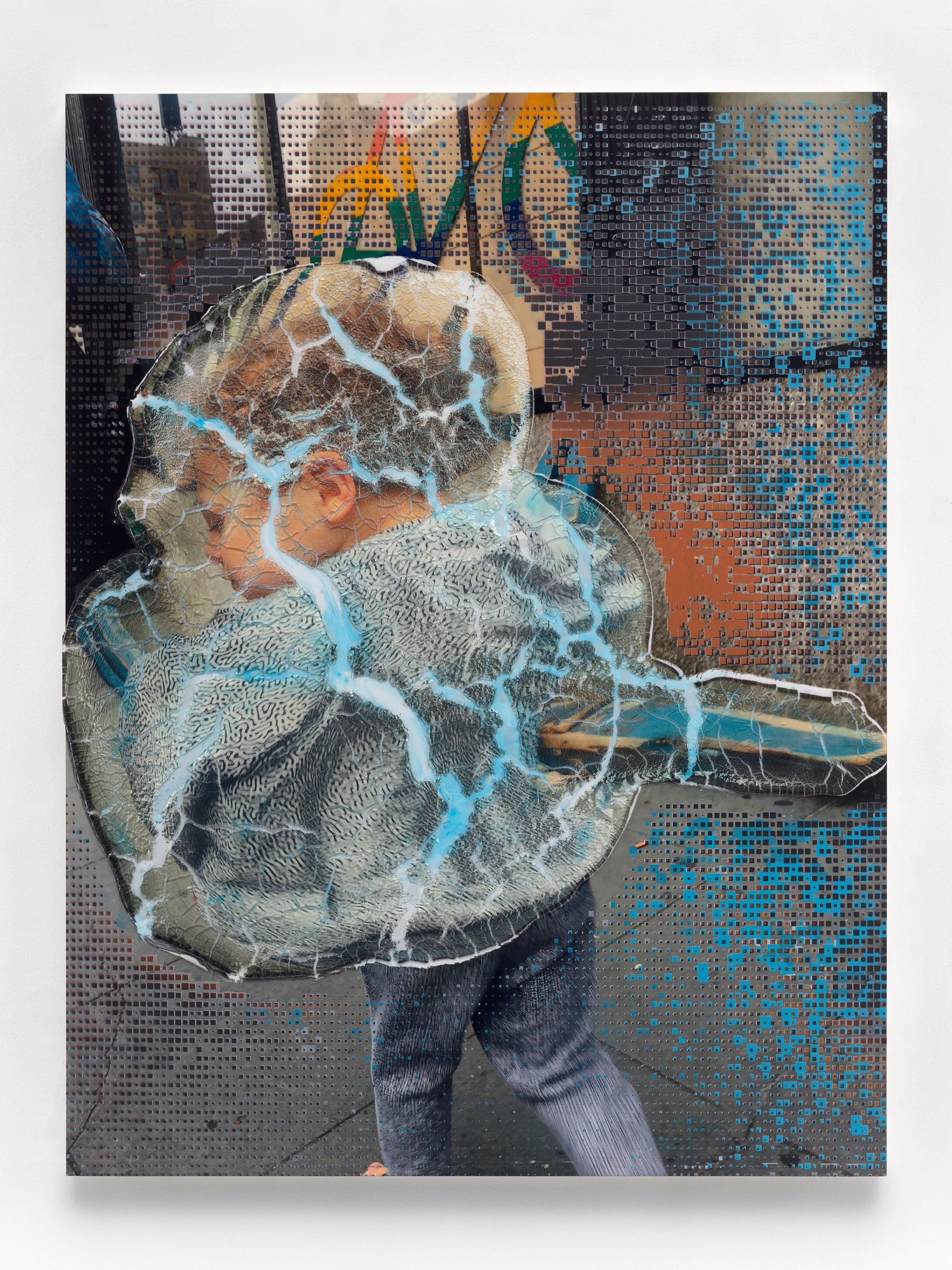

Seth is a materially-focused artist. He’s what I would call a compressionist; he processes the world by collecting its varying shapes and colors and then produces objects or stages experiences that play with the intended function of the material or technological. For instance, in the fall of 2004 at one of his shows for Reena Spaulings in New York, he showed Digital Video Effect: “Spills,” (2004), which features a bulbous television, face-up, packaged in its original box. It was plugged in and playing grainy footage captured in the ’70s by Joan Jonas. The video features Richard Serra, Joseph Helman, and Robert Smithson sitting in a room in conversation about art. The piece dances the line as a videoed sculpture or installation piece.

While reading Fuck Seth Price, one doesn’t have to know how the artworld works to “get” how the artworld works—he shows you what to pay attention to as you navigate the pages with an unnamed and placeless protagonist. On this very infrequent occasion we get to ride on the back of someone who knows where they’re going, and what to steer clear of, so buckle up. Re: questions artists are asked when they do make good work, I did ask Seth a lot of those questions because I really did want to know what he’s been thinking about to really just live in the interiority of the seth-price-world-space and all the things that have consumed him over varying stages of his career. We talked about fashion, art, and a bit more about this theory stuff.

Welcome to The Object Talk.

I was talking to Dan [Graham] yesterday and he was saying that in the ’60s everyone was so focused on or had the desire to be called a writer. Anyone and everyone could call themselves an artist but so few people had the talent or pedigree to be a writer. What does writing take from you? Is it a diaristic practice?

Yes, it’s a practice with a diaristic dimension, absolutely.

Do you have a routine and are you regimented?

I did that once, in order to write a novel, which became Fuck Seth Price. I cleared my plate so I could just sit down and be a writer. So yes, then I felt like a writer. Usually, it’s just random diary time.

Do you think of yourself as a compressionist?

What’s that?

It’s like the saying, “all the best artists are the greatest thieves,” which is to say that you’re an extractionist; someone who is taking bits and different influences and putting them in the bowl and mushing them together and putting it through the meat grinder and producing a “Seth Price” work.

I have worked like that at times. It’s interesting that you use the term extraction. I’ve been thinking about extraction, and how it’s linked to the digital, and the processes of how digital technology works, what it’s supposed to do in this economic regime. It has this brutal, extractive logic to it, and you can feel the violence there, in digital production and communication, or in artworks produced with digital tools. Everything has to be reduced to the same plane, in order to be transacted. It’s something people have noticed with my work, when they talk about violence, or coldness, or alienation.

Let’s talk about Organic Software, (2015). The website that you made is a perception tool for artists to browse to search collectors and art investors who buy their work, where you can also see their political affiliation.

That piece started in a personal way. I found out that an artwork of mine from a show I’d done had been sold to a client I felt uncomfortable with. I found out only after the sale. I was happy to have sold an artwork, but I was also trying to examine my feeling of discomfort. And I started to think that it was bigger than what I was feeling, because, I mean, where does any of the money come from? Once you really look, it can start to get disturbing. So I thought, well, what if we had this resource?

Have you ever made works for the market? Do you think about the market when you’re making work?

No, because when I’m making something, I can’t usually conceive of the end result. I’m not that kind of artist. To make something for the market would mean thinking about what the market wants, in relation to what you have to offer. There’s nothing wrong with that, because art is also a marketplace: on one level, I sell objects to rich people. It’s not the only level, but that’s the way it is, and it’s good to remember that, as an artist trying to make a living, you’re a business. But the market likes predictability. It’s hard for me to conceive of something and then execute it. I try, but I always get waylaid. I mean, I would love to paint oil on canvas, but I just can’t seem to get there, somehow.

Really. Why not?

I always wind up with this weird, other thing. I just get kind of carried along in this process of forces and materials acting on each other, and chance, and changes in direction. It’s not unintentional, it’s exactly what I love about art, that it’s about change, and transformation, and the unexpected.

What’s your relationship to materiality and materials?

All of the works are very material. It’s practically the first thing I’m working with, when I’m trying to figure out what I’m doing. The quality of the material, the way that it feels, the desire to want to touch the object, this is all very important. It’s something that doesn’t come across in a lot of the photographs, because I’m also interested in flatness. But it’s of the utmost importance to me that you can stand in front of the work and just feel it.

What do you think the disconnects of your practice are generally?

There was a time in the 2000s when me and my friends were being called appropriation artists. With a few exceptions, I don’t think it was accurate. Certainly not for me. I think it came out of the fact that we were using digital tools, which are about taking, and manipulating, and recontextualizing. People weren’t used to that, there hadn’t been so much digitally-made art. I made ‘Painting’ Sites; I don’t know of any other artists who were making art with internet searches at that time, in 2000. People would be like, “You’re a computer artist, you’re an internet artist.” So are you, you just don’t know it. Within a few years, they’re like, “I put a filter on my face.” “I scanned my signature and squashed it to fit the document.” People launder their whole life through their phone. I think the issue is, the logic of the digital wants to pull things out of context and manipulate them, and quantify them. That suggests appropriation, but it’s a very different mechanism from the art historical idea of appropriation.

How do you relate to the term appropriation in its current context and cultural reception, having been assigned that label in the early aughts?

I remember talking to some of my friends about it at the time, and our general feeling was like, a shrug. We felt like, from now on everything is appropriation. Ignore it, proceed as planned. I still don’t like these terms, because if we were to speak in an art historical way, using the term as it was defined —it’s the same with “conceptual,” which people also were calling me, for a while. As an industry, we end up with these terms floating around in a very loose way. For a lot of people, “conceptual” just means they kind of suspect there’s more to it, but they don’t know what it is.

What is your relationship to fashion?

The industry? Excitement and confusion, in equal measure. You look at someone’s collection that’s good, and you feel excited, and uneasy, and it’s all whirling around in your mind, and that blend of discomfort and desire is what keeps you coming back.

Can you speak about the collaboration in the early ’10s?

That started Fall/Winter 2011, with a collection I did with Tim Hamilton that debuted during Men’s fashion week. We rented a vacant storefront downtown, on Walker or something, and did a presentation. All the buyers put in their orders—

Really.

[laughs] I’m joking, no one wanted to buy it. But I debuted it in another way, the following summer, at Documenta.

Kara Walker has this studio approach which she calls “retinol detachments,” which is about having heavy non-presence, where she enters the studio and then “conceptually” peels her skin and then enters into a space where she isn’t raced, isn’t gendered, but she is embodied. When you’re in the midst of working do you have to enter a dissociative or possessed state to churn out the work?

Yes, yes, absolutely. Often, when I get home, I’m still in this other realm. I’m not easy to be around, or talk to. Not, like, in an evil, nasty person way, more just like, I’m not in the realm where human interactions come easily. I enter a kind of floating mind space, when I’m working. I like to have a lot of different things going at once, to be able to give in to — I wouldn’t call it distraction, but drifting, taking sudden forks in the road. I like to drift in a non-goal-oriented way, in order to keep everything popping, and not get bogged down.

I’m still not convinced on the fashion bit. What about the architecture of the storefront? Why couldn’t the project just exist as images or as a staging of a catalog? Or something drawn out about the narrative or story of the collaboration?

Why make objects? I mean, that other stuff comes inevitably, anyway, because art installations don’t last. You’re left with just the images, the catalog, the story. That’s the unfortunate part of art history, right? Pick an artist you like and it’s rare that you understand what a given gallery show looked like, and felt like, what was the layout, what was there.

Right.

Because it’s not the way we document these interventions and phenomena. It would take a lot of work to reconstruct what all the shows look like that Kara Walker or Dan Graham did. I think we all know the experience of flipping through a catalog, and turning the page, stumbling across a little black and white photo of a show, and being like, “Oh my god, what? That’s what the show looked like?” With the fashion, it’s always going to exist as a story, a myth, ephemera, photographs. But there was something important in that moment, at Documenta, of staging a shop window in this department store right next to the main exhibition hall, and doing the fashion show in the parking garage. Those were all amazing experiences, to enter into that discourse, and that language. That was a huge part of the project for me, entering into the vocabulary of making garments. At the time, it felt like there was a lot of interest, obviously going back decades, a mutual interest between art and fashion, but there tended to be two main approaches from the art side. There were industry collaborations, where artists were kind of giving some images to put on clothing or handbags, and then there was an interest in fashion in a more generalized, abstracted way that has to do with youth culture, and newness, and taste — I’m thinking about Bernadette Corporation, for example, though they made clothes, too. But I wanted to specifically get into the architecture of the fabric, to design a line, to make sculptural pieces in that industry, in those shops in the garment district, with pattern makers and seamstresses and all that.

Okay so, Bernadette Corporation and Art Club 2000, go!

Right, yeah, it’s all there. But we entered into a different era after the ‘90s, in respect to luxury and branding. Fashion in the’90s was very interesting to me, and a lot of people I knew, you’d go to the bookstore and read the new Face, and i-D, but at the same time, nobody I knew was actually wearing labels, that would have been really uncool in 1995, with the people I knew. The people that were wearing, like, Prada were—

That fashion gworls?

[Laughs] They’d be “euros,” like, wealthy students from other countries, where there wasn’t a punk heritage that said you’re supposed to look scruffy. People here who wore labels were tribal, there’d be skaters wearing Fuct, and ravers wearing Danücht or something, and club kids from New York in X-Girl. This was before streetwear was something everyone fucked with. People I knew were wearing unbranded stuff, thrift store clothes. It was that Naomi Klein, “No Label” thing.

That’s my vibe. [Laughs] I don’t fuck with labels.

We all experienced this massive conglomeration of the industry, LVMH, and all the consolidation. And then music, rap, all sectors of the culture became interested in luxury, right? People were now interested in Vuitton.

Right, this obsession with the necessity of labels.

Yeah, it’s aspirational luxury, I think, if you have to use a phrase. I think that’s a different approach to fashion than this slightly earlier generation of artists, not that someone like Bernadette Corporation wasn’t going to fuck with luxury, because they definitely were, but luxury itself changed, the circuits around it changed. I think we consume culture in particular circuits, and that makes up kind of an affective relationship to the culture. In the ’90s, it was magazine time.

I saw in Dispersion that you write about magazines, and then when I was talking to Dan, we spent a lot of time parsing through his relationship to magazines as well. What’s your relationship to magazines?

I used to go to the bookstore and get a giant stack of magazines, and sit there for about two hours until I read them. These days, I just don’t.

Right. What’s your relationship to collecting? What do you collect?

Stuff kind of accumulates. I’m constantly going through books and music, but I’m not a collector. I was just having this conversation with somebody, because I have a large library of music, but I’ve never collected records. I might buy something on Bandcamp, and I like to own files, because I’m not into the Cloud. But I’m not fetish-y about objects in a way that I would buy vinyl. I’ve never bought any art. I don’t really collect anything, actually. You can make power objects without being a collector, you know. When I was little, I had traffic cones that I would steal off the street, and I would take hubcaps from the gutter, from accidents, and I collected rocks. I once nailed a Twinkie to my wall because I wanted to see what would happen, and left it there for a few years. Nothing changed about it, except there was a grease stain on the wall.

Was this pre- or post-Maurizio Cattelan’s Art Basel Banana?

Oh, this was in 1983. [Laughs]

You went to Brown [University], right? How did that inform your process and how you engaged with the world afterwards? Were you making work while you were there? What were you thinking about?

I was making film and video work, and making drawings and things in my room. I didn’t take any studio art classes, but I was doing a lot of thinking, and reading, and talking to people. I didn’t have a plan of what I would do after school. I don’t know if you can do that, today.

What was your “focus”?

It was in the Modern Culture and Media department. Which is still around, but much expanded now, more legitimate. This was the place in the university where you would find Postcolonial Studies, Post-Structuralism, Semiotics, Queer Studies, Cultural Studies, and Television Studies, which was a thing back then. All of this was very suspicious to a lot of people in the university community, because things like [Michel] Foucault were not yet being taught in the History department. In the mid-90s, it had this kind of circle-the-wagons mentality. My concentration was in what they called “Art Semiotics.”

What does that mean?

It basically meant that you would read everything, and take part in seminar classes, but you also had to fulfill a production component. “Production.” [Laughs]

Right. [Laughs]

Which in that department at that time could only mean film and video. Within that tradition, coming out of literary theory and feminism, film was seen as the exemplary art form, because it was discursive. So I did film and video. I studied video with [visual artist] Tony Cokes, and film with [avant-garde filmmaker and artist] Leslie Thornton.

Oh, interesting…

Yeah, those were my gurus, at an early age.

How did engaging with them as these embodied figures and people with practices shape your worldview?

Huge. They were doing unabashedly experimental work. And they were just being themselves, showing this insane work in class, like, “This is me—anyone have a problem with that?” And sometimes people would, in fact, have a problem. They’d walk out of the class, because they came to study independent film or something, based on a popular idea of what independent, narrative film was in the early ’90s, and this was explicitly against that. For me, it was liberating. I remember, though, there was still a split between video made in the art world and in the experimental film world. The tradition at Brown had nothing to do with Independent Film, but it also was not the art world. Leslie showed a video that a British artist had made from the YBA scene, and people in class kind of booed it. They hated it. It was someone in a public park, I think, making strange noises. It made an impression on me, because it was such a different approach.

So, what happened when you graduated from Brown?

I knew that I didn’t want to go to art school, but I did apply to the Whitney [Museum] Independent Study program.

Why’d you apply to ISP?

I wanted to be in New York, partly because my girlfriend at the time already lived here. She’s also an artist now, Chitra Ganesh. So I was going to New York to live with her, and I applied to the ISP because it would give me something to do. I did not get in. A friend of mine who worked there told me the director thought I was being “crazy” in the interview. But I needed a job, so that first year I worked in an office stuffing envelopes, you know, linoleum floors and fluorescent lights. I poured drinks on a private party boat that would go around the island. I did film PA work. I worked at Maysles Films.

Does drawing feel like something that you have to labor over?

It’s not labored, no.

Is it something that you sit down to do or is something that you’re always doing?

I’d like to be more disciplined about something like that, and say, “Today I’m going to sit down and draw.” I would like to be that person, but that’s never been how I’ve operated.

Let’s talk about your most recent project, Dedicated to Life. It feels like a manifesto for living and an emotional and humorous guide of how to live and experience culture. Who are your references?

References? I don’t know, some weird, self-published poetry book that you’d find in a bin somewhere. Again, that’s an example of how I couldn’t imagine that the book would be the product of this prolonged process of working. It was the result of many forks in the road.

What were these forks?

It started as the attempt to write a young adult book, which didn’t work. Instead, I ended up writing Fuck Seth Price. But I had, like, 250 pages’ worth of failed YA novel. I started pulling excerpts out and breaking them down into things that are structured like poems, in other words, they have line breaks. Sometimes when you just shift the context, or the frame, it can make things interesting to work on again. I never set out to make a book of poems and drawings. It kind of suggested itself as a frame for these other materials.

How do you structure the writing? Do you write rhythmically?

I think if I set out to write a poem, I would have been thinking about rhythm and structure and style much more. In the end, the process was pretty quick, it was more about treating the text as a found object. It had been some years since I had written any of that stuff, or even read it.

How do you normally approach writing? Are you keeping tabs and writing down bits as you experience them? What’s your relationship to memory?

It’s that kind of vibe where I have an idea, and write it down in Notes on my phone, and send it to myself, then put it in a Word document and slowly start to find connections, and work out some connective tissue.

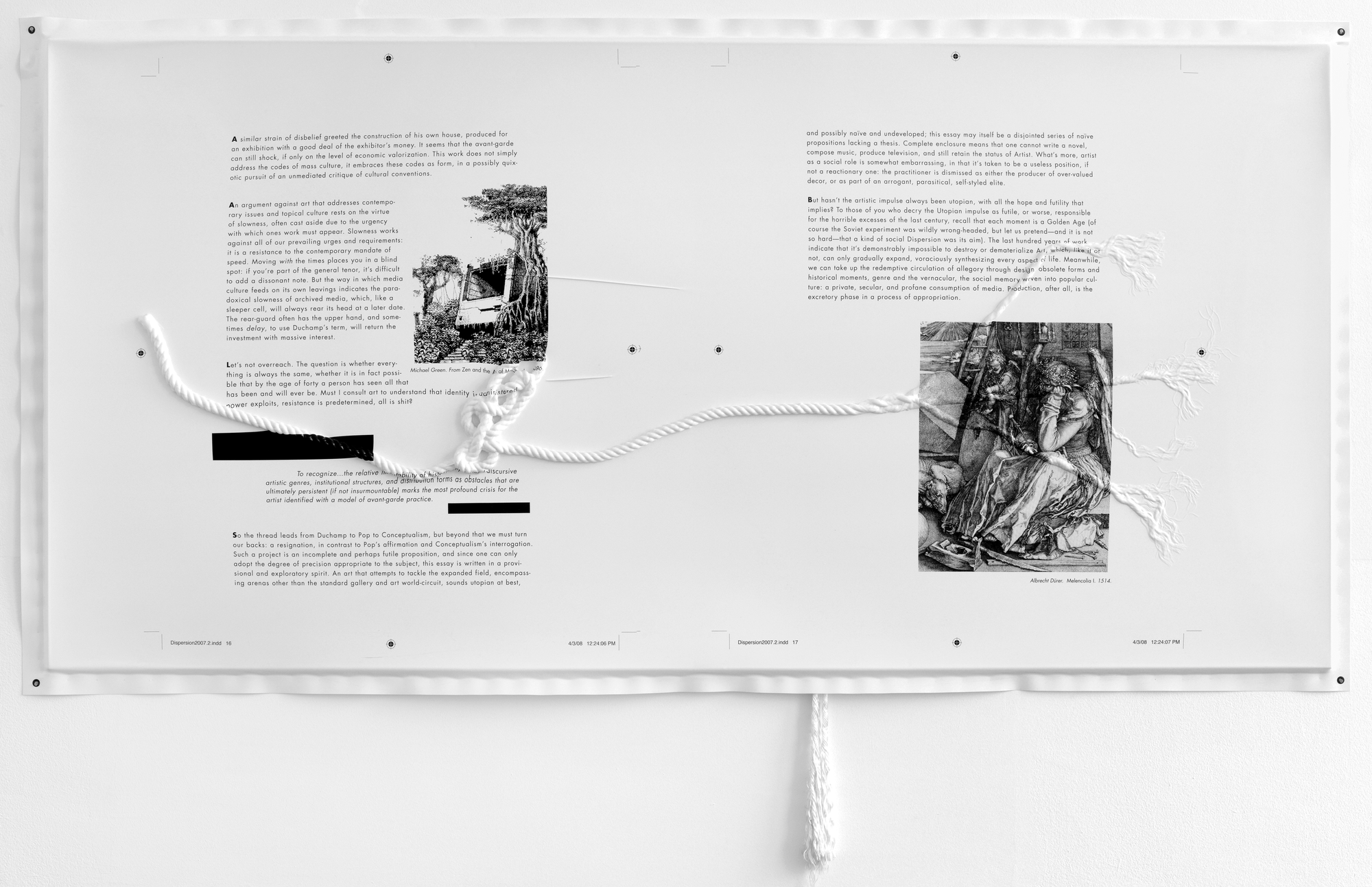

How did you approach making Dispersion an object, beyond being an object?

You mean as a book? Yeah, so, it was first a PDF, and then a booklet—

And then as a work?

Right. It was a set of plastic panels, screen-printed, and vacuum-formed over knotted ropes. I wanted to have it exist as a constellation of things, not just the one thing. A painting can be self-contained. I wanted this to keep pointing to other things.

Was that a retroactive decision or was it a driving desire?

It was my interest for some years. It came out of thinking about someone like Dan Graham, who could write an essay called Rock My Religion, and also make a video called Rock My Religion. Or how [Robert] Smithson could write an essay, make a sculpture, and make a film, and call each one “Spiral Jetty.” And the physical, sculptural work in the desert is the one that catches the imagination, and becomes the iconic image, it’s the thing people mean when they say Spiral Jetty. But at the same time, it’s the iteration that is least accessible to people. Whereas the essay and the film are probably most accessible, they’re probably online right now. At the time, I was thinking of Dispersion as an artwork that would kind of enact its own ideas, by circulating in these different ways. There were some new economic possibilities and stratifications coming out of digital culture, you could work with redundancy. You could have a free version, in this relatively new internet economy, which would circulate endlessly, and then it would also be a book that was ten dollars at an art bookstore, and then you could also engage with the art economy, which is the gallery or the museum, with its own structure of prices and audiences. And the piece would spread out.

In Dispersion, you wrote about Duchamp’s concept that the artists of the future will be underground.

Yeah, I think it’s an important thing to keep in mind. This might seem romantic, but to be seen and named is great, it feels good, but it also makes it easier to quantify you in terms of value, and I don’t just mean financial value, it can be critical value, social value, value for someone else. And those can be gilded chains. The more you are known, the more you are predictable and testable and constant, and can improve in value—

How do you feel about being made into value?

It’s weird, for sure. I mean, if you’re lucky enough to be made into value, you’re in a good place. But it can be strange, it can be alienating. Although that’s how it is for all of us, now: always being made into value. All these platforms are tools for changing material conditions. Just by using the tool, you’re changing material conditions. Even if it’s not happening for you, it’s happening for someone. That’s alienation, right there. I will tell you that we need to bring magic to materialism. That’s my project.

Subscribe to Broadcast