Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF

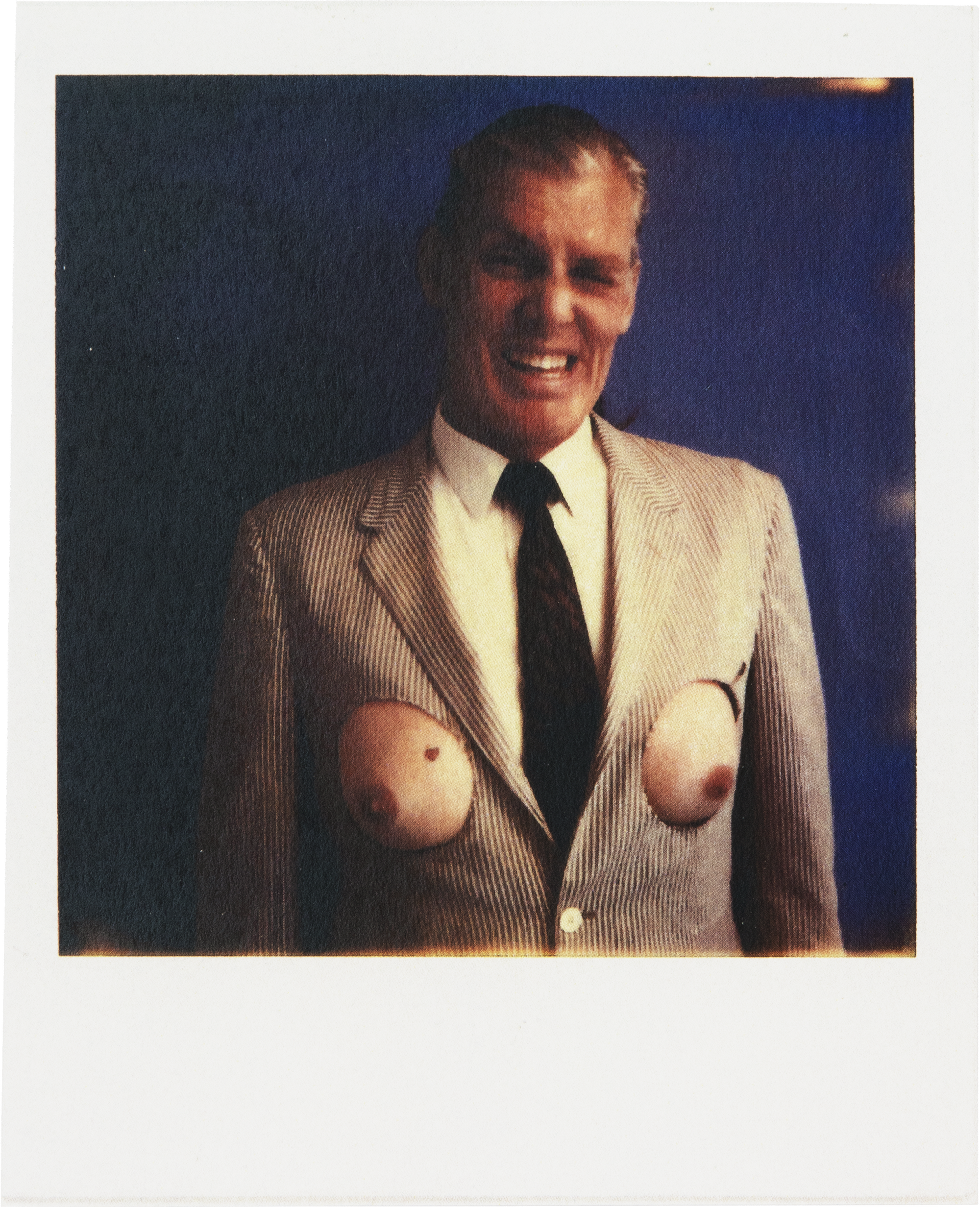

Pippa Garner, HE 2 SHE, 1995.

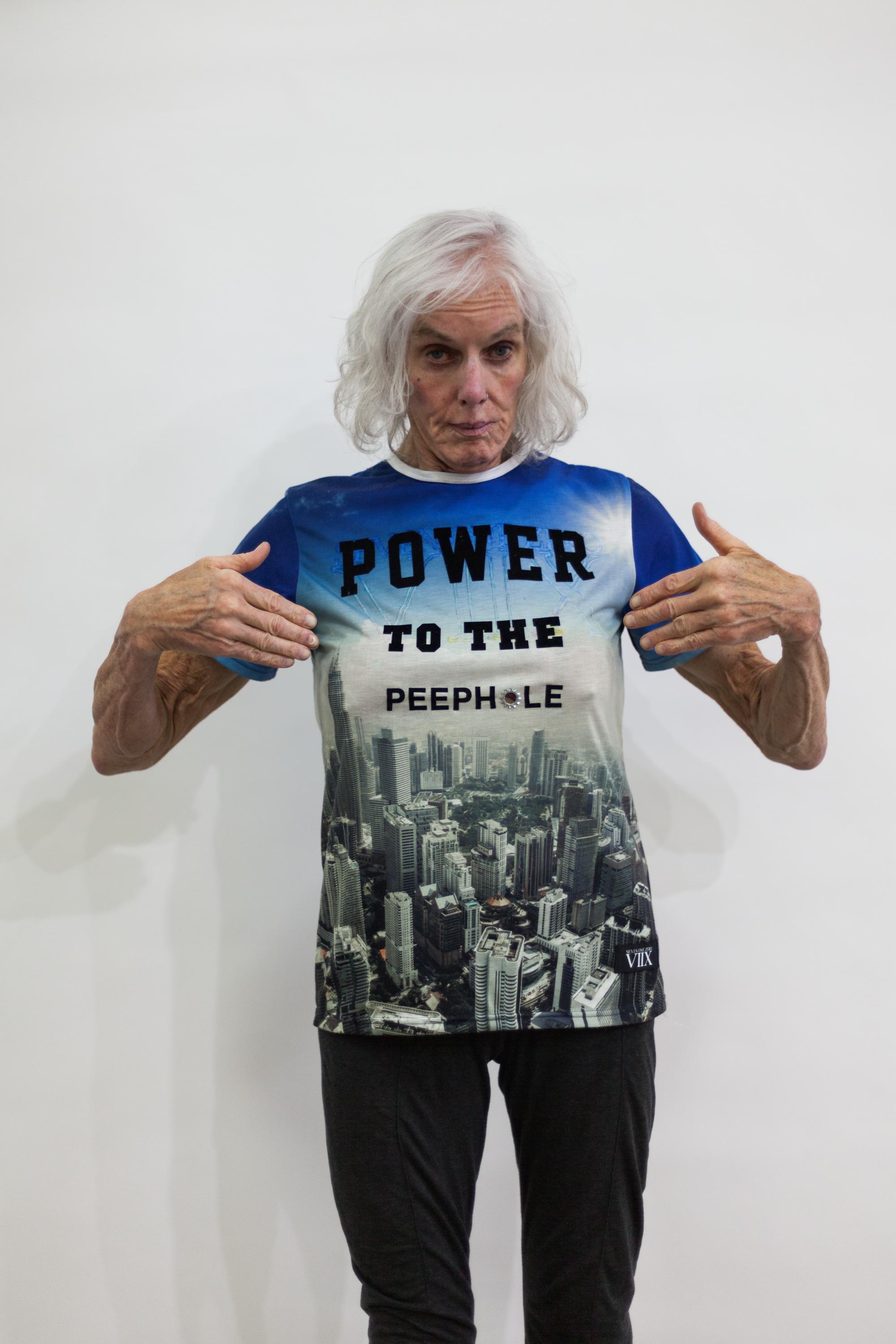

Pippa Garner has been doing things the wrong way for a long time. She’s engineered a car that drives backwards; designed a dramatically cropped, gray sport coat for warm weather; invented objects that don’t make any sense, like a broom combined with a boombox; and customized hundreds of T-shirts that brand their wearers a “creep magnet” or “bad in bed.” In each instance Garner has made the marketplace monstrous, and turned the norms of American domesticity inside-out. She made things queer when queer was contentious.

This fall, Pioneer Works Press has partnered with Art Omi to publish Pippa Garner: $ELL YOUR $ELF, a 352-page book that spans the five-decade career of a woman who has made it impossible to look away. The book is full of unseen photographs and writings by Garner and her admirers, tender and punchy, and serve as anecdotes for those for whom reinvention is survival. In an age where identities are mined and commodified, Garner has been a mirror whose work magnifies our deepest insecurities to show us that the best way forward involves making fun of ourselves. The following is a collection of never-before published writings by Pippa herself—excerpted from the volume launching next week at Pioneer Works.

—Micaela Durand

Pippa Garner, Manette, 1992.

Mission

As an artist and humorist with a penchant for technological satire, I’ve “reinvented” mass-produced artifacts to create items of tempting appeal but dubious value, as in my books: THE BETTER LIVING CATALOG and UTOPIA ... OR BUST! Recently I became a product of my own juxtaposeurial tendencies by undergoing sex-change surgery. After a half-century as a competent hetero male, I committed gendercide and was reissued as a “man maid” postmenopausal adolescent female. I have realized my ultimate art goal: to “be” one of my own ideas. I feel like my brain is the remote controller for an animated toy (my body) and it can’t wait to try her out in each new situation.

My next objective: A legal self-marriage (masturmony?)

—Philippa Garner, 1995

Autobiography Part II

I have no memory of any inward struggle over whether or not to take female hormones. The idea presented itself and seemed absolutely right. It was as if any ambiguity had been worked out on a subconscious level and by the time it came to the surface, all was clear. It was just a matter of procedure—how does one go about such a thing? Naturally, I went to the doctors, three of them, all of whom thought I was crazy or stupid or both. I also sent for a pamphlet titled “Hormones and me,” which I saw advertised in a magazine. This proved to be amateurishly produced and vague, but contained a certain amount of information. I did not see myself as a transvestite or a potential transsexual, I just knew somehow that my maleness had run into trouble. I spoke to no one about this. Nancy was the only possible person I might have confided in, but I couldn’t overcome the need to play a male role with her, even if I played it badly. She knew I was going through a hard time and told me later how worried she had been, but there was nothing she could do. I began approaching transvestite street hookers and offering to pay them for information. After several false starts, I met Kellie, a sad but very nice transsexual who agreed, for a fee, to sit at a bus stop and brief me on the use of hormones. It was through her that I found the black market source for female hormones that I have used for the last five years. After that night, which included a demonstration of the use of the syringe, in her motel room, I never saw her again. The second mirage.

I was incredibly elated at having accomplished this strange mission. I became adept at giving myself the twice weekly injections in a short time. All I hoped for initially was that my breasts would develop. I anticipated no other changes. After several weeks I noticed a kind of itching sensation around my nipples accompanied by a slight swelling. Within a couple of months my skin had softened enough to draw a few compliments but the real change was psychological. All of my complex frustrations ranging from my economic failure to my convoluted feelings about women began to dissipate. My sexual feelings opened up into a wonderful sensuality. In short, I became, in the space of a few short weeks, a new person. Nancy was the eye witness and couldn’t believe what was happening. (She didn’t know about the hormones for the first six months. By then, my breast development, although slight, was enough to give me away.) I began to feel that my pre-hormone life was that of another person. I had stepped out of that skin and was, at age forty-five, beginning again. I was discreet about revealing any of this—it was illegal—but once the word got out I took every opportunity to promote what I thought was a revelation of major proportions. The problems of the world could be summed up in one notion: too much maleness. Eventually, nature would take care of this, but in the meantime, man could take evolution into his own hands and achieve Utopia through hormone balancing. I have a file of the pages of notes I made during this initial “over-reaction” period. I will get them out someday.

There may be an aspect of truth in these first thoughts but in looking back—it’s been five years—I believe I was using these generalizations to mask the true nature of what was happening to me. I had awakened the female within me, given her the kiss of life, as it were, but was denying her the strength of her character. Of course, these things take time and it is interesting to me that I went through this virtually alone. What would have happened under guidance, I can’t guess. I think most people regarded this as another Garner “crazy stunt,” along with my Backwards Car and other notorious projects. People in LA tend to be blasé and cynical—they’ve seen it all. Most of my lecturing fell on disinterested ears. The bottom line was ... “Did it make any money?” So I remained very much on the far periphery of the local scene. I wasn’t ostracized, I just wasn’t included. It was still primarily the money thing.

I had acquired two very loving Persian cats and they covered a great deal of my need for friendship. Nancy was going through troubles of her own, but had achieved great recognition as a painter. We remained soulmates. I was doing good work (even if I wasn’t getting paid for it) and things were actually pretty good. The only real problem, and it was becoming a big one, was LA itself. I had been there a long time, twenty-five years off and on, and I’d seen it go from what amounted to a sprawling small town, full of eccentricity and absurdity, to a tough, self-centered, and humor-less megacity, overpopulated and ugly. I knew I should get out but I felt stuck there, partially because of my bond with Nancy, and the fact that I didn’t want to leave her there alone.

And then one of my little cats, the most loving creature I have ever known, was killed in Wilshire Blvd. What I went through when I found her little body I wouldn’t be able to describe. I was destroyed. I felt like I had died with her. I cried for days and even now I can’t talk about it. My father had died the year before and although I was sad, my feelings were abstract. When I lost my little cat, it broke my heart. I knew then I had to leave, as soon as possible.

There was no question where I would go. I would return to Mill Valley. It was the antithesis of LA and seemed like the ultimate vision of paradise. My mother had moved to Sausalito and was willing to help me meet some of the costs of moving to a more expensive place. I left in October 1990, just in time for Halloween in San Francisco, vowing never to return to LA again (except briefly, for a lot of money, under highly professional circumstances). I’ve spent an idyllic year and a quarter here in my rustic flat, the bottom of an old house on a quiet tree-lined street. I now have four cats—three from Persian Cat Rescue in Livermore, a shelter for abused and abandoned Persians—and one of my cats from LA: a friend of eight years. Some of my high school acquaintances still live here but we have little in common at this stage. My mother moved to Mill Valley a few months ago and I get together with her once or twice a week. Our relationship is good at times, testy at others. I have mentioned my gender ambiguity a couple of times but I don’t think it sank in. Her current project is to “find herself” after forty-nine years of marriage.

The last thing I want to do is confuse the issue by introducing something she would undoubtedly find bizarre. I have reinstated my most important personal routines such as the gym, which, to save time and money, I built into my apartment, and regular attendance (twice a week) at a dance club. During the past months I have taken the change of environment as an opportunity to experiment with painting and forms of expression that I never would have tried “down there.” It was satisfying and successful but for the new year I decided to go all out for a commercial success, at last. I am working on a new book which will be styled after my first book (the one that got away) but I am going to profit from my mistakes and make this one work. I started ’92 with a strong sense of impending personal evolution. Things are moving. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast