On the World Folding Onto Itself

Curator Nora N. Khan speaks with artist Umber Majeed about Trans-Pakistan, a speculative travel agency and genre-defying research practice that investigates the simulated present through the lens of Bahria Town, a planned community in Lahore, Pakistan.

This interview happened in June of 2022 and appears in Software for Artists Book: Untethering the Web, which will be released on October 1, 2022 for Software for Artists Day. It has been edited for length and clarity.

***

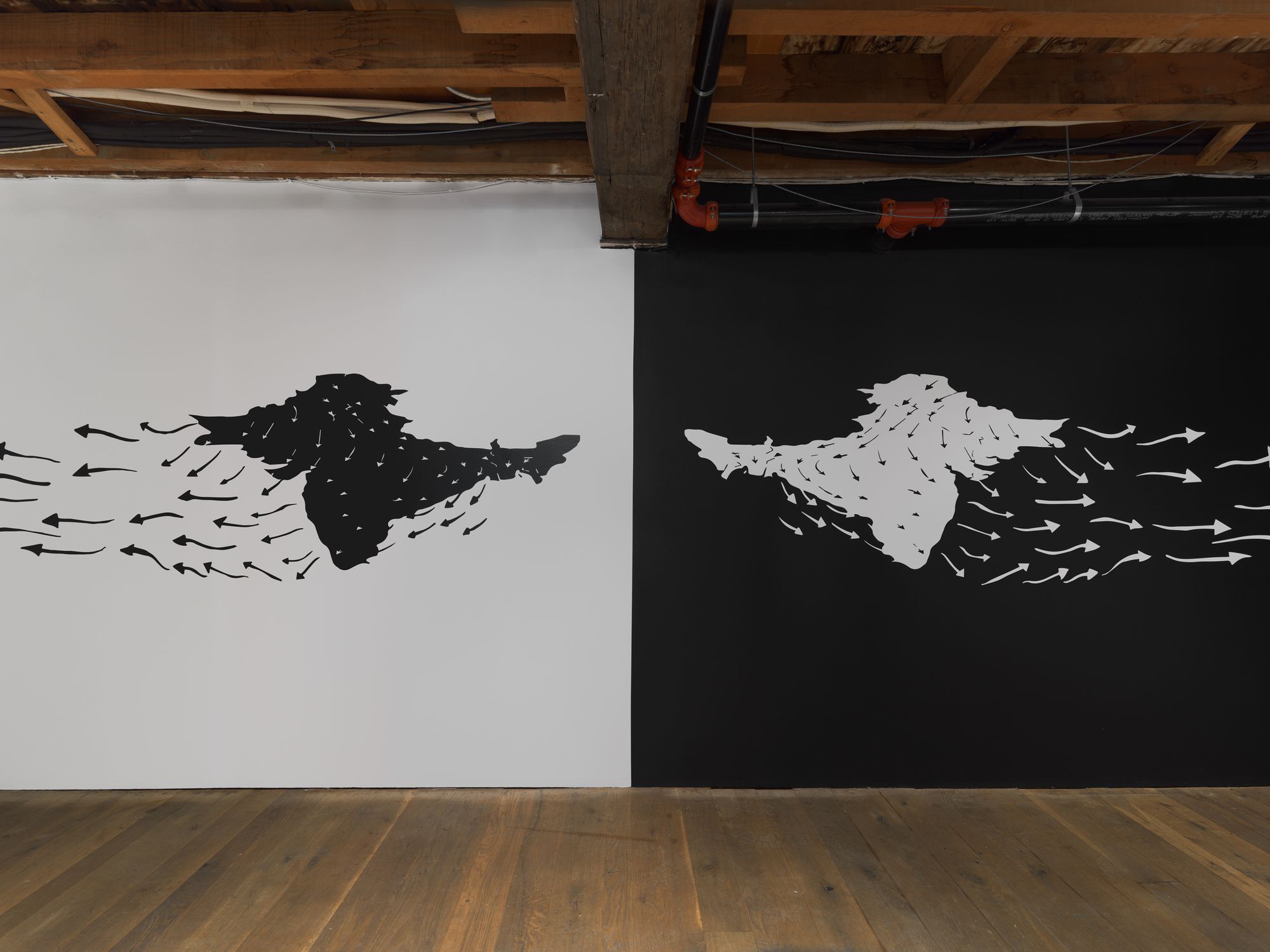

I have followed Umber’s inventive, researched, moving—and funny—work since meeting her in New York in 2016, but I only had the chance to work with her last year, for a digital art show I curated, Experimental Models. She contributed Fotocopy.net (2020), a looping clip of a blue man walking counterclockwise around a globe, on a set that’s instantly recognizable as “South Asian digital kitsch”—her term. During the course of a roundtable on Zoom with her and the other artists, we talked in depth about the work: how the man’s movement seems completely counter-intuitive, as it models a reversal of several hundred years of map-making so that South Asia drives the flow of capital.

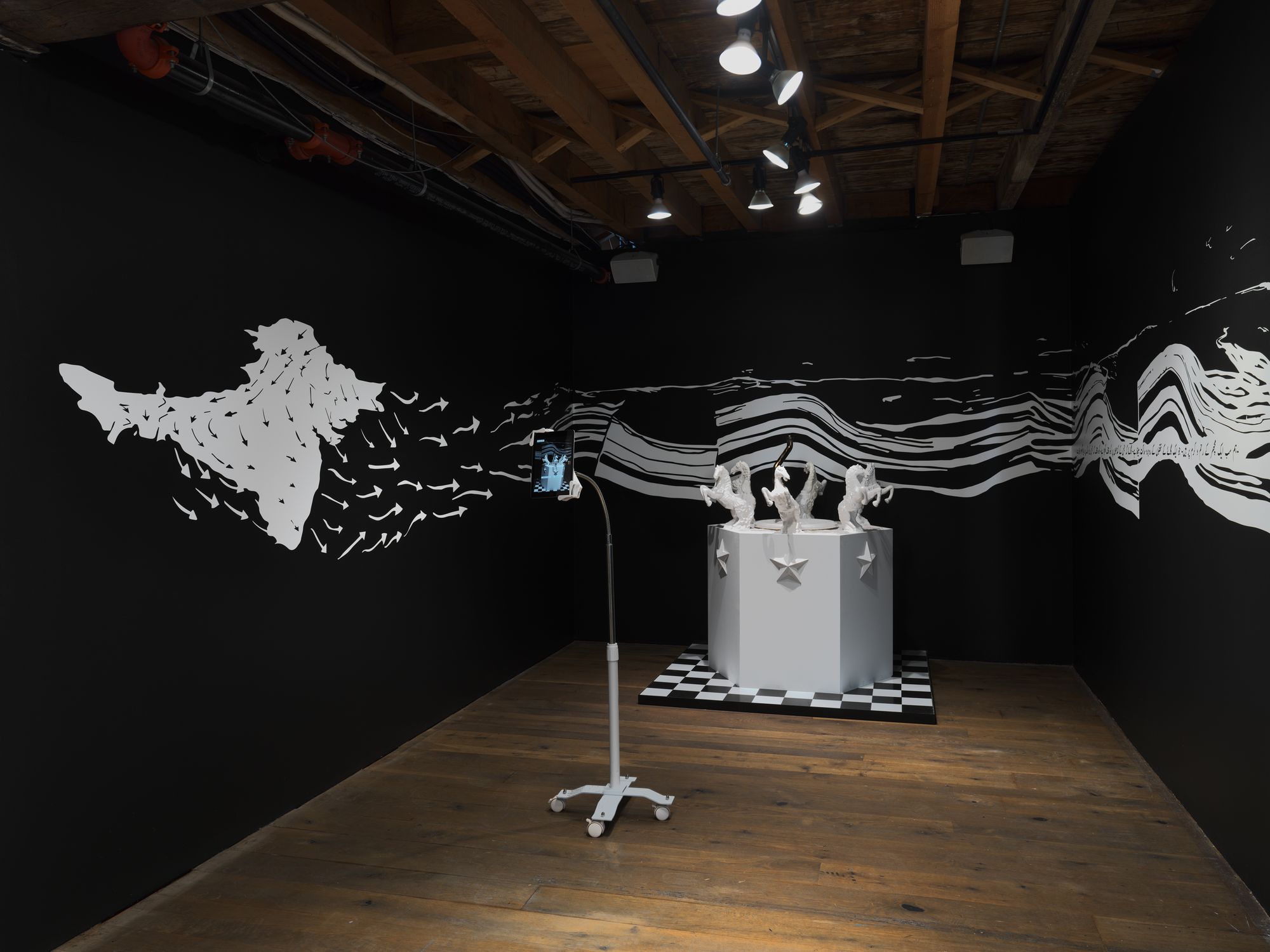

In her Pioneer Works exhibition Made in Trans-Pakistan—part of her larger Trans-Pakistan project, which takes its name from a fictional travel agency—Umber rounds out a long exploration of Bahria Town, a constructed planned community on Lahore’s outskirts, which has replicas of the Taj Mahal and the Eiffel Tower. She mines the symbols embedded in Bahria Town, a successful leisure destination where simulation comes before authenticity. The show

combines augmented reality, found material, and ceramic horses with QR codes, leading to an interactive web environment where we can “draw” outlines of copied ceramic animals at the edges of Bahria Town.

In Made in Trans-Pakistan, Umber focuses exclusively on Trans-Pakistan as a fiction, which helps people travel further into the fiction of Bahria Town: worlds folding in on themselves. There’s an emphasis on repetition and iteration, on the introduction of grooves, glitches, and interruptions. Umber hunts, she tells me, “for objects in [her] daily life that will help build out the speculative travel agency, which will then help people walk through the fiction of Bahria Town.” The fictional agency is rooted in Umber’s uncle’s plans for a travel bureau that never quite got off the ground, stymied by Islamophobic travel policies throughout the early aughts. Trans-

Pakistan becomes a metaphorical guide, a worldview, both the eponymous travel agency and a speculative Trans-Pakistan archive.

More recently, re-watching the blue man’s movement, Umber asked, “Are we learning a new fiction? Is that what we’re doing, by flipping his movement backwards and counterclockwise? Is this counter-use?” I find endless overlaps in practice and sensibility with Umber’s work, her pastiche of fragments—words, phrases, incantations, memories, images both physical and digital. In this is a roadmap to a new fiction, which might be of a commune in the coming apocalypse, or, an updated copy of this world.

I have a memory of an armoire, somewhere, which I’m told holds family heirlooms. I imagine a few slender objects our parents brought with them that became anchor points for world-crafting. You don’t need to begin with much. A piece of costume jewelry. A ragged photo folded three times over into a wallet.

I want to start with the fragment, the remnant, as the entry point into your world-building in Trans-Pakistan.

That is how I started. I brought over materials from my grandfather’s photography archive: his analog photos, his prints. He had Alzheimer’s, unfortunately. He suffered a number of strokes. So he was paralyzed. I wasn’t always able to get context for the photos, what we call objective or factual information. “Where did you take this photograph? What camera did you use?” I didn’t have any of that.

But I had his prints, and his notes on the back. I had some of his letters. I had his equipment. And there was the context of repetition. I would find, because of his dementia, he would consistently and obsessively photograph the same lamp. That repetition meant something. It wasn’t about the lamp. No. It’s his condition; he could not center his memory in a linear fashion. I worked from this point. When I don’t have all the information, how do I find entry points to give new life to those objects, to create alternative contexts or realities around them?

In Made in Trans-Pakistan, I’m reconstructing new contexts using little remnants of objects that are familiar, with their attached economy, labor issues, and politics. My mom just found this radio that she brought when she came to meet my dad in Toronto, in the ’80s. She had a red radio, an old-school boombox. That was the one thing that she brought with her. My dad would send her Bollywood cassettes while they were long distance. I found it and said, “Oh, I’m definitely going to make my own sound installation using this.” I remember the way she talked about it, this radio, how deeply her migration story was attached to it.

The radio as a talismanic object. Carried along with her, for protection. How does your research process feed your world-building? There’s movement forward, folding back, a continual revisiting of ideas? If there were ever a diasporic sensibility… Your work, with careful looking, unfolds these layers of longing and nostalgia. You assemble your findings and references (the research archive desks!) while refusing a demand for resolution, a full picture. Artifacts are generated by the fragmented, partial knowledge. Atop the themes (post-colonialism, globalization, neoliberalism, all mixed) sits a lush, textured, pastiche style. You reveal the grids, edges, the cuts of your making. We see the seams in your virtual landscapes, too; they seem stitched together.

For Trans-Pakistan, the process took a couple of years, over which I practiced different methods of archival research. I’d experimented in other projects with family archives. I’d reinterpret a given state or family history. But Trans-Pakistan allowed me to do something more specific; I wanted to tweak, play, and I wanted to explore loitering. I previously used green screen to create a recognizable aesthetic; to reinterpret and intervene in the given aesthetics or language of the Islamic Republic. I’d make offshoots and alternatives, parallel histories within my own work. Now I am able to go a step further. I was less interested in conveying Bahria Town in real time; I wanted to create a sense of a particular time and space. I was also interested in slowing down time, whether through counterclockwise or counter-use.

That blue man in your set piece, walking counterclockwise around the globe!

Him. And, speaking of global movement, I traveled. I researched housing communities in Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad. I went to Dubai to research. I picked up what was familiar, following a process of intuition. I’d have a visceral feeling whether I was in a marketplace in South Asia or in Sharjah sourcing fabrics to export. At one point, I’m in Islamabad, in one of Bahria Town’s upcoming phases. They had just built half of an Eiffel Tower in a barren landscape that’s soon to be beige houses. What is Bahria Town doing? What am I interested in doing in Bahria Town? People are now paying 5 rupees to go up and down this Eiffel Tower, to see these beige houses. That’s the view. You’re seeing just beige houses and dirt. There’s awe in just this: here is what people are paying for. The ride up and down this simulated Eiffel Tower is their global accessibility. My original premise was to do something on-site in Bahria Town, with the local community, with the artisans that work on the animal sculptures. This could be a walking tour, an augmented reality experience in which I collaborate with Bahria Town as Trans-Pakistan.

But people often get lost in the idea of the copy culture that Bahria Town embodies. What Trans-Pakistan is trying to advocate for is that there are multiple copy cultures that overlap each other. The copy culture commons that I’m interested in is rooted in piracy. Repetition is expansive. Can Trans-Pakistan create its own stock archive of imagery and material that people can access, and play with? It can live where it was originally proposed to be on-site. There is also this online archive where the material is open source, generative, and user-generated. I’ll run a workshop where I teach people to make a lenticular postcard, based off of an image from the Trans-Pakistan archive. Participants are asked to insert any kind of object into the postcard. This makes it a Trans-Pakistan postcard.

What do you think of the desktop, virtual set spaces, these small simulations where we see the edges? We see the artifice, the edge of the world.

I was thinking of them as sets. Well, it’s hard for me to navigate virtual spaces. To create this interactive web environment, it was important for me to have a task that referred back to the hand. I embedded a game which focused on the gesture of drawing. You are presented with panels which you can fill in kids’ drawings. It’s a playful invitation: Welcome to this space of

Trans-Pakistan. You can loiter in this space. You can listen to the music, look at the visuals; you can draw.

I’m obsessed with the liminal space between the entrance and exit of Bahria Town. It’s above a canal that has toxic garbage and waste. Each of the sculptures are hung by barbed wire, so each looks like it is floating. The reflection of the animal sculptures are in the water. The way the animals are set up outside of Bahria Town looks like a set. I’m now making molds out of a garden sculpture that I got from Pakistan and brought here. It broke a little bit, but we’re keeping it a little broken. I’m integrating the whole procedure of mold and cast in fiberglass; they re-cast the sculptures and copied them. I’m extracting to make this set.

Let’s take up this throughline of multiple copy cultures. There’s your hyperfocus on repeat phrases, like the ubiquitous (translated from Arabic) “In the name of God.” Or, specific loaded replicas, like the simulated Taj Mahal, itself a Vegas export, in Bahria Town. A copy of a copy takes on its own aura. I’m curious about when you talk to visitors learning about Bahria Town through your research. You’re never didactic, but the story of the simulations being given “the right” through Pakistan’s Supreme Court to occupy space, feels like a literal model of experience in the digital, virtual, or software space. Where the simulation becomes reality, reality modeled after, well, the model. There’s no focus on an original or authenticity but instead a pervasive comfort with living in a world of fakes, copies, and endless replication. People understand the logic of simulation on a core level. What do you think of simulation through the story of Bahria Town?

I’ve come to terms with the idea that my audience is not necessarily “South Asians” or “non-South Asians.” My audience isn’t South Asian diaspora; it’s diasporas. It’s those who’ve been alienated. Pakistan is a case study. Trans-Pakistan investigates, uses all the nitty-gritty details particular to this place, to much bigger ideas. And people often don’t believe that Bahria Town is real; they think it’s fiction, like Las Vegas. I think the work of Trans-Pakistan is to be ultra-specific. The concept of authenticity is not a South Asian, or a MENASA, or a SWANA region concept. The entire point is not to be. Look at Mughal art. The only way that artisans and artists made anything is through copying. That’s how they honed their craft. Copying is the foundation. In poetry, you need to copy, to reinterpret for the translation to move. Copying generates an ongoing dialogue.

To learn is to copy is to be in relation, along a continuum with other people. You take up this iteration and versioning, at its core.

I had a recent conversation with Asad Alvi, my translator, who's doing a PhD in Texas. We spoke on unfolding Urdu, the ways the language unfolds within itself. I was speaking of a specific translation of an Urdu verse, which is about the world folding onto itself. He presented four or five examples of that through the writing of Urdu poets, including feminists—Urdu modernist poets. In Urdu poetry, motifs are repeated. Writers integrate these motifs and keep repeating, and adding onto them, and twisting them. It’s a never-ending conversation.

Is that what diasporic artists and writers are trying to do: continue that conversation? Are we, instead of using specific words as the correct vocabulary, instead focusing on the mood, the rhythm of our inherited language, the aesthetics? Maybe that is why it's so recognizable on a visceral level.

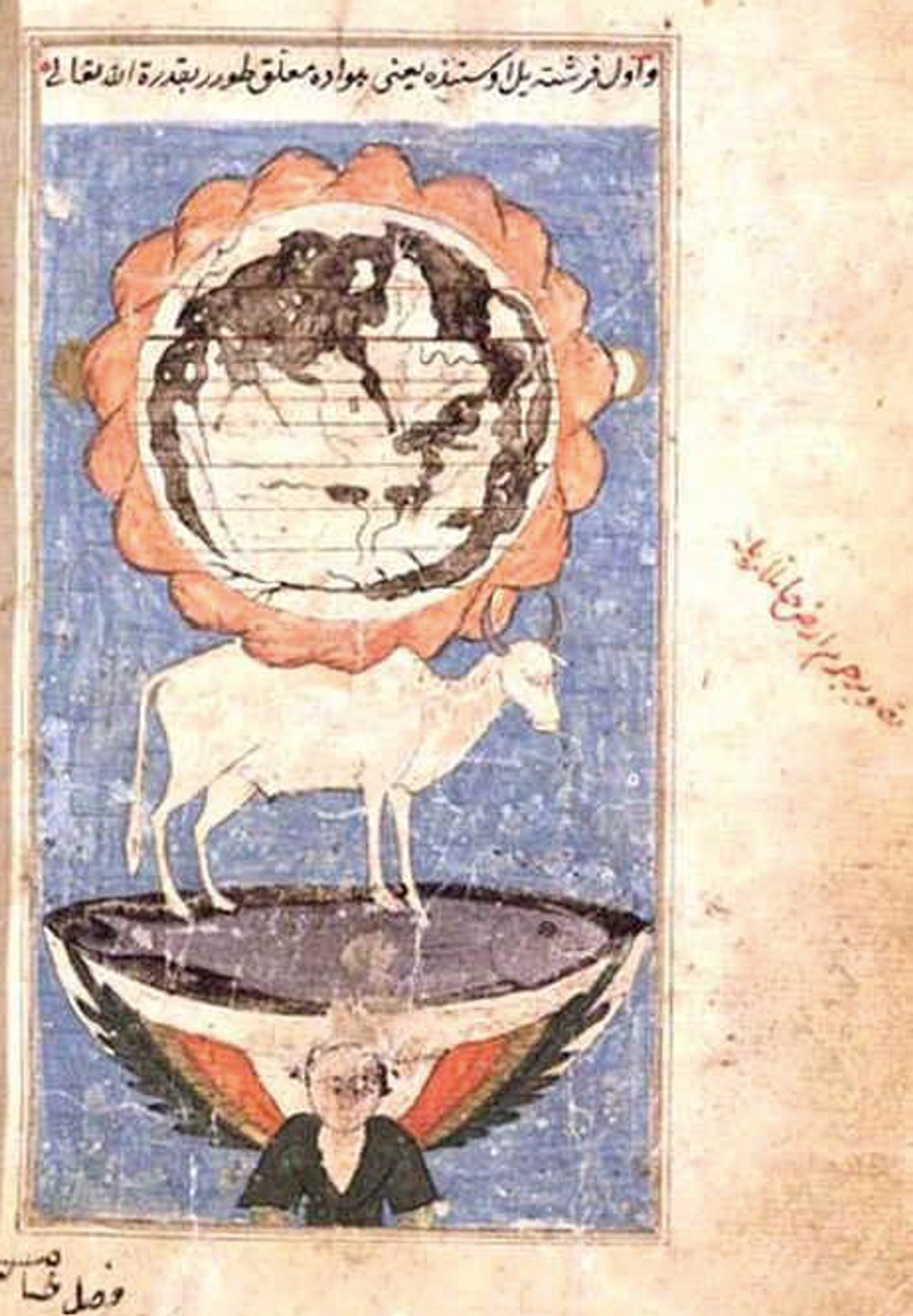

Then there’s the imagery. Asad told me about a poem about world-building and ecosystems. There’s a folk tale about a writer whose grandmother told him that the world is actually round, and is balanced on a buffalo’s head while standing on a fish. This is folk village storytelling, oral storytelling and imaginary. To think of that visual, and then about how the world is in balance

only in relation with another ecosystem.

There’s the scholarly writing around the Qur’an that’s related, of the world on a whale, a bull, or…

Yes. These images are derived in relation to later interpretations of the Qur’an that fester into this poem’s world-building.

The para-text around the main text, the generated images peripheral to the central story.

That imagery has traveled in or through poetry over generations. Poets refer to that field of imagery every time they talk about origin stories, whether folk or scientific. Everything is grounded. As is the perception. Even sci-fi stories set and born in villages in South Asia will return to this imagery: It’s grounded in animals, their ecosystems. We are part of a whole collective imaginary, enmeshed in that. That visualization is the commons; that is that grounding, that moment of balance and play.

Translation is profound! Meeting one another at the word, at the text to construct the context around it. There’s a moment of recognition not just of a story but an aesthetic, a sensibility. We might look at repetition in qawwali, the repetition of refrains in intensifying, escalating loops. When you are trained in English writing, “don’t repeat yourself” is a mantra for editing, for “good writing.” But in Bengali, you repeat yourself and the phrase means something different depending on the context, on where it falls in the song or the poem, on the emotion in the voice. The same phrase can mean a thousand different things, depending on how it’s said. If I repeat a phrase in English, I mean it differently each time. Our language allows us to reconstruct contexts that have been lost.

Installation view of Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan at Pioneer Works, September 9 - December 11, 2022.

Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy of Pioneer Works.

Installation view of Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan at Pioneer Works, September 9 - December 11, 2022.

Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy of Pioneer Works.

Installation view of Umber Majeed: Made in Trans-Pakistan at Pioneer Works, September 9 - December 11, 2022.

Photo: Dan Bradica. Courtesy of Pioneer Works.I don’t think I’ve ever thought about that—of repetition as expansive. In the act of repeating, the repeated becomes something else. That’s what I think the task of Trans-Pakistan world-building is. In its multiplicity, it begins to embody a whole other thing. And what helps me is that I’m not in that context. I’m not in South Asia. I’m working in the U.S., and I show in Europe. In workshops, I introduce Umberto Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality (1990). We talk about copy culture starting in that scene when he visits Madame Tussaud’s.

How is the replica of Paris in China different from the replica of the Eiffel Tower in Pakistan? These are different audiences, and so the copy works through different mechanisms. There’s local corruption. The workshop is where we dissect this context together and unpack it together. The context of copies lays the groundwork to focus on copy culture in South Asia, which has a specific tie to piracy and copyrights, all reimagined in this urban landscape. It’s happening on this land and they’re experiencing it.

Trans-Pakistan takes that experience and extrapolates it. Part of the experience is digital, but it is still grounded in the body, on land, and in the urbanscape. It is a metropolitan experience. I can’t water it down. I can only, in every iteration of the work, clarify this context further.

I appreciate how heavy the theory is in this piece, how woven it is throughout without being explicitly named. I hear Fanon and Edward Said and Sara Ahmed. The agency feels like a roving probe deconstructing these different spaces. Its filter, whether AR or a frame, allows one to see the structure and logic of the fiction of home, of patriarchy, of the state.

You spoke of your audience as multiple diasporas. Exile and distance have always brought me perspective. To never go back home in 40 years maybe allows one to see the structure of the ideology of home in a way that one could not see when in it. I see, say, the logic of neocolonial expansion better from a distance, how it’s shaped my lineage or my origins. Famines, catastrophic wars. Colonial logic still, of course, reverberating. I’m curious how do you see distance in diaspora helping you see beyond a place’s surface or exported narrative?

I find it interesting that you describe distance as allowing objectivity: not being in thrall to the mechanism itself. I have had the opposite experience. Things only become clear for me when I get closer and experience a space all over again. There’s the moment the fiction crashes or collapses. I’m interested more in which fiction I am disintegrating, even if it’s of our future dark commune of the apocalypse. That is also a fiction. The nation state is a fiction, and borders are a fiction. If I’m going to have to uphold a fiction, which one am I going to choose?

Speaking of many fictions: to think of growing up in a place like Pakistan. Every time you turn on the news, it’s corruption and lies. Everyone’s living under the rule of survival of the fittest. You don’t know what the truth is. In the context of Bahria Town I am watching the South Asian diaspora reproduce a homeland that does not exist, which they have reinterpreted from the last time they left the country, and then brought it back with them in a return migration. The design is that one global world you’re talking about, except it’s a colonized mind moving back and forth between. So that distance and objectivity has never been there. It’s been “tainted” from the onset. I’ve had constant movement in my life. The only time I was not in Pakistan I still maintained a dialogue with it. I’ve done this my whole life. And every time, I come back different.

As I grow, I make choices that make the fiction visible to me. The choices we make in how to move in these contested spaces that we are a part of—and that are a part of us in some way—is the work. While scattered, and not categorized, the Trans-Pakistan archive is particular. There’s nothing unnecessary. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast