Living on Earth

Our human lives have a fair degree of definiteness to their boundaries. Where each of our bodies begins and ends in space is pretty clear (give or take the bacterial colonies inside our guts—those might be in some ways part of us, and in other ways distinct). The same is true of our beginnings and endings in time. Each of us begins from a fertilized egg. The new individual grows up and develops, while keeping a fairly constant form, before growing older and dying.

Other organisms are much less definite in their beginnings and ends. When a bacterial cell divides, is the result two daughters and the death of the parent, or does the parent live on in one of them? If so, which one? A tree might send out a root that initiates a new stem, and if the root breaks, the two trees are entirely separate. Is that something like a birth? And where are the spatial boundaries of “the” tree while the two stems are still attached?

For life to continue, there needs to be a way of preventing metabolic processes from diffusing away into the surrounding chaos. Compartments and borders of some kind are necessary. This is the role of cells. But when many cells are working together, there’s no need for these larger units to be always neatly marked off from each other. Living things often have vague boundaries, and this is another reason why it’s common to think about ecological systems using biomass rather than counts of individual organisms; in a lot of cases, it’s not at all clear how the count of organisms would go. This applies to plants, corals and many others.

Now let’s turn to the mind. It seems, at least, that our minds also have pretty definite boundaries, tied to those of our bodies. If there is no afterlife, then when I die that will be the end of my mind. Each of our minds is, it seems, “owned” by an individual person, and private to that person in many respects. This relationship might have some exceptions and qualifications. In rare and fascinating cases, physically conjoined twins seem to have a partial unity, or at least very unusual contact, across their two minds. “Split-brain” patients are another variant.

All these phenomena shake up our expectations in a useful way. And they lead to a question about how things might have been, or how they might be elsewhere. Could the mind, as a feature of life on Earth or another planet, have evolved in a massively spread-out and extended way, merging and blurring rather than being tightly associated with distinct individual bodies and forming individual selves? Is it an evolutionary accident that matters are the way they are here? I want to suggest that it’s not much of an accident. The kind of individuality present in animal lives like ours has connections to the evolution of the mind, including felt experience, and the messages here relate to our boundaries in both space and time.

A crucial fact about reproduction in animals like us is that we each emerge through a “bottleneck,” a one-cell stage. Our bodies are rebuilt in each generation from scratch. This seems in some ways a waste. If you want to grow up and get big, why start out as small as you possibly could? But the one-cell stage has a lot of importance in individual development and in evolution. The rebuilding from scratch, the fresh start, enables a small mutation in the genes of one cell to ramify through all the cells as they divide to make the new organism. A small change can affect everything in the body.

All this gives rise to something close to a discrete start to each life, in animals like us. It also has consequences for aging and decline. For various reasons—competition, external risks and threats—it makes sense to grow up and become able to reproduce earlier rather than later, as long as you’re able to do the job well. It’s also worth taking on costs that come due later in life, in order to do well at earlier stages. For many animals, this means that a natural decline tends to happen after reproduction, on a rough but reliable schedule.

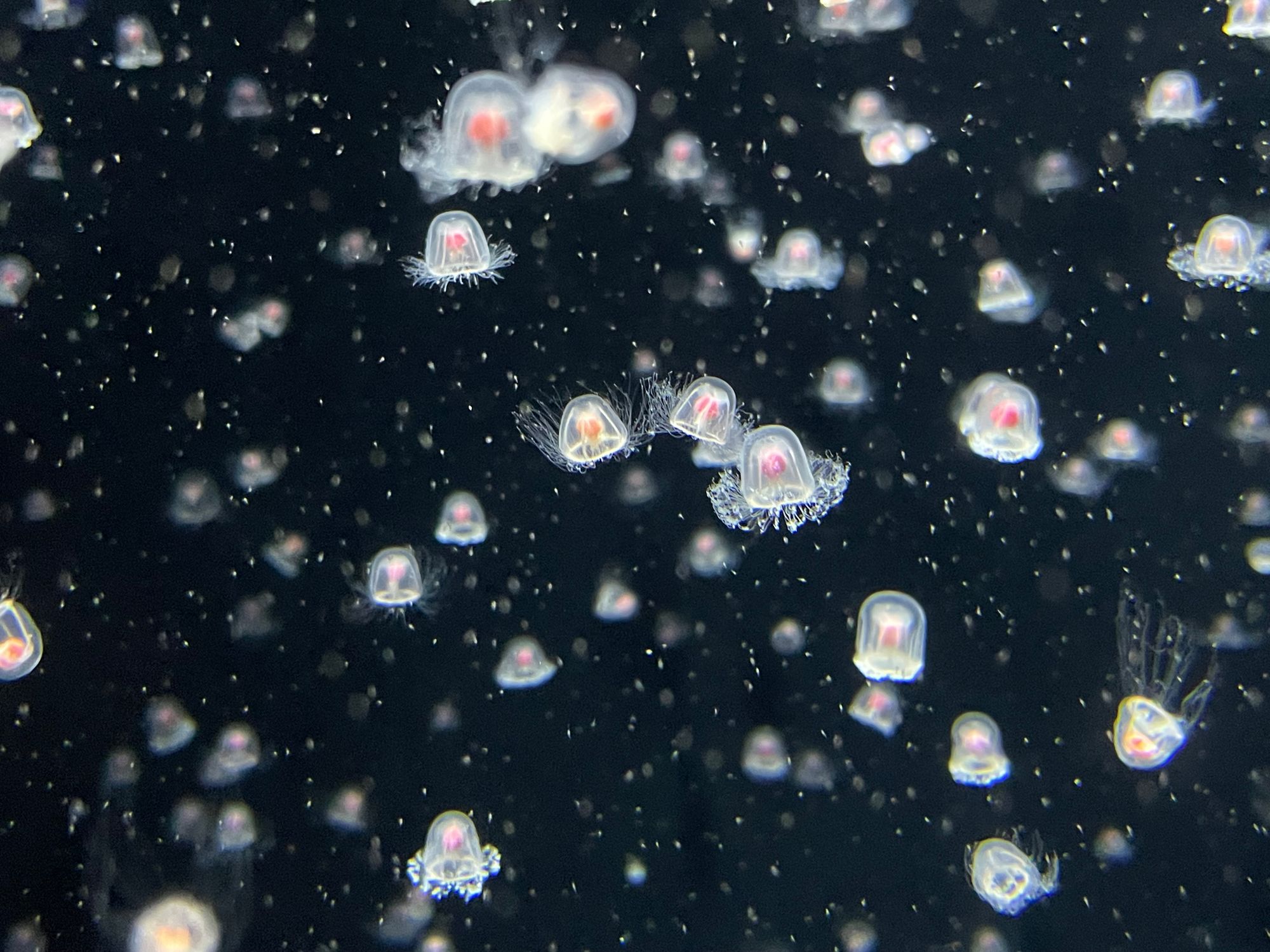

I don’t want to oversimplify. The “immortal jellyfish,” Turritopsis, reaches a particular stage in individual development and then turns around and runs backward towards a more juvenile state, and can turn around and run forward again. It has a much simpler body than we do. If the animals of some species could avoid external threats indefinitely, and very old individuals of that species also had an advantage in reproduction that never abated (large trees are a bit like this), then the usual forms of internal breakdown might never appear in those animals. Even when that’s true, the ends of these lives will still be definite when they do occur. They can’t, except in some simple cases, divide in two and continue on, or disintegrate and reform. There’s a pattern here: animals who are capable of felt experience will be behaviorally complex and mobile, hence unitary in organization, reproducing through a one-celled bottleneck, and with a pretty definite beginning and end to life. It’s no accident that felt experience is associated with our kind of body, and also with our kind of path from birth to death.

Might all this change in the future, with new technology? Even if the shape of our lives and deaths make sense in this way, even if it’s all biologically comprehensible, we can still step back and ask what we think of this arrangement. Should we just accept it? Or should we fight it, and try to take a different course?

*

If human numbers dropped enough, my view of immortality (or dramatically extended life) might indeed shift. I might start to worry about losing the human project, and see a need to stretch each life out as far as possible. When I say this, I assume in this scenario that we have started to do better with our care of the Earth. But whether we imagine a future with a great many humans or fewer of them, I would rather retain a world with turnover, with new lives, not one where the same individuals go on and on and on. In nearly all cases, I would want to give up my place, hand on the baton, myself.

I understand the point of thinking through the more far-fetched scenarios—the endless, disembodied, cost-free mental continuations. I can vaguely imagine a completely different physical basis for my existence, and then I might see the idea of turnover and endings differently. But we can also think about our situation in a more realistic way, with our physical nature on board. Here we treat our minds not as barely housed, floating, ghost-like beings, but as parts of the material world as a whole, embedded in evolution and the Earth’s development. When we see our nature in this way, you might still take on an attitude of total resistance to mortality, but you might instead find yourself at home in this coming and going, this coming onto the scene and departing from it. It’s not just that thinking through the biological side of our existence shows that it would have been hard to have things any other way, and this makes acceptance of our lot easier. That’s not what I have in mind. Rather, this coming and going is part of the Earth’s history, with all its creative character. I identify with that process, including the turnover and renewal, the flow of new arrivals who then depart and leave room for more.

In my discussion of wild nature, I said that one can feel a sense of kinship, and something like gratitude for being part of [a] whole. This sense can be more strongly expressed as an identification with the processes characteristic of our enlivened Earth. Those processes include, for beings like us, lives that take the form of a journey, being brought into existence by nature’s energies and then dissolving back into them, as others have before. ♦

Excerpted from Living on Earth: Forests, Corals, Consciousness, and the Making of the World by Peter Godfrey-Smith. Published in the United States by Farrer, Straus and Giroux, September 2024. Copyright © 2024 by Peter Godfrey-Smith. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to Broadcast