Hypochondria

One day in 2010, I got a headache. The pain was not severe, but it was constant—accompanied by a strange feeling of belatedness which meant that, when I first became conscious of it, I knew it had already been going on for some time, lingering just beneath the threshold of awareness. How long exactly, I couldn’t say—weeks, definitely. Maybe it had been years.

After about a month I visited the doctor. In those days, this was not a knee-jerk response. This must have been at the start of June because it was warm out, and I remember that I was on my way to return a suitcase and two shopping bags full of overdue library books—something that, to my discredit, I did only twice a year, on the first Monday after the end of the winter and the summer terms.

The doctor had an earnest, warbling, confident way of speaking that, in spite of her evident commitment to the tenets of mainstream medicine, gave her the unshakeable air of an alternative healer. She explained that what I was experiencing were called tension headaches, an ailment that was common among students and during exam season practically universal. I said that I didn’t feel very tense. The doctor asked whether the pain felt like a tightness across both sides of the head. A kind of squeezing? Like an elastic band being pulled tight? Like a fist clenching around your skull? I said that it did not feel like these things. Yes, she said, nodding meaningfully. Every person experiences tension differently.

The doctor asked me what medication I’d been using to manage the pain. I was thrown by this question; the thought had not occurred to me. This was, in many ways, quite surprising, since I have never been a person to make a virtue out of forbearance and actually consider my tolerance to pain to be less developed than the average. In the case of this headache, however, my attitude was edging closer to that of Franz Kafka. A century earlier, the writer told his soon-to-be fiancée Felice Bauer that he never took aspirin because doing so, he said, created "a sense of artificiality" that in his opinion was far worse than any "natural affliction." Aspirin had been developed a few years earlier in the laboratories of the Bayer Company. Originally intended to treat rheumatism, it quickly gained popularity among healthy consumers looking to ease the ordinary pains of modern living. However, for Kafka it was vital to pay attention to every aspect of one’s existence, no matter how small or seemingly trivial; which was why, as he later said, he made a habit of viewing his life through “microscopical eyes.” As Kafka explained to Felice, if you had a headache, you had to undergo the experience of pain and treat it as a sign, before examining your entire life, right down to its most minute detail, “so as to understand where the origins of your headaches are hidden.”

The idea of taking painkillers struck me as irresponsible, even reckless, like disconnecting a fire alarm because it has interrupted your sleep. Besides, the pain itself was bearable. Only its persistence concerned me, the meaning of it. Like Kafka, I wanted to understand the headache. The doctor told me to come back in a few weeks if things hadn’t got better, sooner if they got worse. I left her office holding a bottle of aspirin, which I promptly deposited in the bin.

*

In her short essay “In Bed,” Joan Didion writes about the chronic headaches that she suffered from on a weekly basis. Didion begins by explaining that migraine is an inherited condition, a “physiological error.” By the end of the essay, however, Didion is describing a sly complicity between the migraine and its sufferer:

We have reached a certain understanding, my migraine and I. It never comes when I am in real trouble … It comes instead when I am fighting not an open but a guerrilla war with my own life, during weeks of small household confusions, lost laundry, unhappy help, canceled appointments, on days when the telephone rings too much and I get no work done and the wind is coming up.

The migraines that regularly kept Didion hauled up in bed appear to be an unbearable yet not entirely unwelcome remission from the aching responsibilities of everyday life. And in this sense, a sort of pain relief.

My headache was nothing like that. My headache was very bearable. Terribly bearable. So that instead of extricating me from my everyday life, it pushed me deeper into it. I became irascible, morose. My entire life came to resemble one of those days when the wind is coming up; one of those days when in answer to the question “what’s wrong?” we are obliged, through gritted teeth, to answer “nothing” so as to spare ourselves the graver indignity of uttering “everything.”

As summer wore on I occasionally noticed myself not noticing the headache. I might be swimming, or making love, or reading, and it would happily occur to me that I no longer felt any pain. However, this reflection always served to drive it out of hiding, and the mild, negligible pain would resume its place at the forefront of my mind. These were not spells of remission, therefore, so much as lapses of attention. As time passed, they became fewer and farther between.

By autumn I had started noticing lots of other little anomalies. I became forgetful. Words kept escaping me. In a crowded bar one evening, I spent 15 minutes trying to guess where I’d met the bespectacled, aloof young man in front of me, certain that he was playing a game, not letting on. Until, annoyed and frankly a little unnerved, he finally said, “Look, I’m just trying to get a drink.” I developed a twitch in my left eye, which would refer down to my middle finger, so that in lectures I always seemed to be tapping out the unsteady beat to some inaudible tune. One pupil became slightly larger than the other and coffee started tasting weird and metallic. One morning I turned on the tap and had no idea whether the water was hot or cold.

I developed a very mild but persistent case of the hiccups, just one, two, maybe three solitary little hiccups each day. Can hiccups be caused by brain cancer? I asked Google. Yes, it answered—if it is advanced.

My symptoms multiplied. At some point I began to keep a list of all these things as they arose, doing so on a loose sheet of paper headed SYMPTOMS, which I stowed in my sock drawer. Reading back over that list, it struck me that it resembled the descriptions of illnesses that I browsed online. But I also felt there was the risk in setting all this down on paper that it would give weight and solidity to a set of experiences whose most maddening quality was their shimmering insubstantiality. It’s true that there were times when these phenomena occurred simultaneously, times when they condensed into something like a palpable disease. Or at the risk of putting things a little dramatically, when these sensory glitches had seeped so deeply into my experience of the world that, as I once explained to a friend, it felt as if reality itself was becoming sick. However, these periods were punctuated by spells of relative calm. Days would pass by without incident, perhaps when I was busy, happily industrious, unconsciously embedded in life. But in a pattern that was becoming familiar, no sooner would I reflect on the absence of these disturbances than I would start to notice them again.

You could say that my attention was producing these things; you could say it was revealing them.

*

For all its tenacity, there is something wispy about hypochondria, with its preference for the slight and subtle, its attunement to what might be nothing at all. To be a hypochondriac is to assign the most important role in one’s life to something that no one else believes is real, and therefore to embrace a certain tenuousness. Little wonder it is often called “phantom illness.”

I think this is why my hypochondria was always worst at night: with nothing else to distract it, my mind latched onto vaguer things. Shapes flickered overhead, my ears sang, while thoughts that had been successfully banished during the day passed freely into consciousness. Most crucifying of all was the thought that I had let another day slip by, another day in which, had initiative and resolve not once again been found wanting, I might have done something about it. That whatever was going to happen to me, it would be entirely my fault. No sooner would this thought occur to me than a parade of awful images would dance across my mind’s eye.

Friends knew about all of this, knew that I worried about my health, that I was spending a lot of time at the doctor. But I don’t think any of them really understood just how much of my mind had been given over to these fears which, even at their peak, I knew might be unfounded. None of this speaks to any failure of empathy; the gap separating our minds was greater than that. In fact, even for me, as I look back today, it is only with a sort of amused contempt that I can look upon that anxious sleeper.

*

“Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick,” writes Susan Sontag at the beginning of Illness as Metaphor. “Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.”

With these metaphors, Sontag is suggesting that there is a clear border separating health and sickness. This is a defining feature of the medicine that has flourished in the liberal economies of the West—where, as Artie Vierkant and Beatrice Adler-Bolton have argued in Health Communism, “health” and “sickness” are heavily politicized, and policed, terms that determine who does and who does not deserve access to state provisions that are always, and by definition, supposed to be scarce. The Marxist critic David Harvey has gone so far as to argue that sickness under capitalism is defined as the inability to work. This is the reflection that leads Deleuze to hear an expression of hypochondria in Bartleby’s enigmatic statement “I would prefer not to”—words that wreak havoc and disrupt the flow of capital in Melville’s famous “Story of Wall Street.” And so we might say that, a full citizen of neither kingdom, the hypochondriac quietly protests capitalism’s ableist demand that the “healthy” body always be a productive body.

A recent Autoimmune Association survey found that more than 45 percent of patients who go on to be diagnosed with autoimmune diseases have been labelled hypochondriacs in the early stages of their illnesses, while in the United States half of those who go on to be diagnosed with endometriosis—a potentially debilitating condition affecting 10–15 percent of people with wombs—report being initially misdiagnosed with a psychological condition, with physical diagnosis taking on average seven and a half years from the first appearance of symptoms.

This is a recent chapter in a long history of conditions being labelled psychosomatic when their symptoms fall outside the paradigms of current knowledge. In the nineteenth century, for instance, sufferers of multiple sclerosis were often regarded as hysterics, while the neurological symptoms of tertiary syphilis were regarded as a form of moral insanity. It is only very recently (largely due to the sheer extent of long COVID) that the sufferers of post-viral conditions have begun to receive widespread recognition for the physiological basis of their symptoms.

However, we have to acknowledge that here we are also in the territory of the so-called “contested” diagnoses such as Morgellons disease, a condition with no accepted medical basis, whose self-proclaimed sufferers have formed themselves into online advice and advocacy groups as they aspire to the patienthood that would recognize (and listening to some of them, one is tempted to say alleviate) their suffering. For psychiatry, sufferers of Morgellons are indeed sick, but not in the way they think; in fact they are suffering from a mental illness called “delusional parasitosis.” Meanwhile in the late nineteenth century, when around one in 10 adult men in Britain had syphilis—a disease that could lie dormant for decades and which, at that time, had no test or cure—newspapers and psychiatry manuals began warning of an epidemic of a new disease, responsible for a string of suicides, that was variously called syphilophobia or venereal hypochondriasis.

All of which is to say that hypochondria is never simply the patient’s condition. The question of who the hypochondriac is, what’s the matter with them, always speaks to the current position of medical knowledge—the ways in which, at any given moment, its categories account for, and do not fully account for, the spectrum of human suffering. Hypochondria, therefore, can function like a sort of waiting room, albeit one in which not everyone’s name will finally be called.

We would prefer to believe that there is a definite border separating the normal and the pathological because this would make it possible, at least in theory, to know for certain that one is on the right side of it. If the hypochondriac is rarely a welcome presence, then surely this is partly down to the way they cast light on the unsteady boundary separating health and illness, the fact that it is not fixed once and for all, the way it continues to shift as diseases are discovered, reformulated, reimagined.

We might say, then, that hypochondria serves as a useful, if humbling, reminder of the limits of medicine’s knowledge. In which case, the peremptory confinement of the hypochondriac to the ranks of the mentally ill—a patient whose symptoms might be treated, say, with antidepressants or some sessions of CBT (an “anxietyectomy”)—represents a denial of those limits. Moreover, making this judgment would require us to assume a diagnostic omniscience that begins to make the hypochondriac’s uncertainty seem like the more credible position. I’m not denigrating medical knowledge, but I am suggesting that by suspending the diagnostic impulse—our claim to know for certain either way—we’re able to catch sight of an uncomfortable question that is posed by the hypochondriac. A question that cuts right to the core of all our relationships, as thinking beings, to our physical bodies: to what extent do we ever know that we are healthy?

*

“Strictly speaking, there is no science of health,” writes the philosopher Georges Canguilhem. “Health is organic innocence. It must be lost, like all innocence, so that knowledge may be possible.” If health is a form of innocence, a sort of unselfconscious flourishing, then what does this mean for an era of ever-extending knowledge about disease? What happens to health in societies that are concerned, precisely, with health?

In premodern times, disease adhered closely to the subjective experience of illness. This is because there were only very limited tools for distinguishing the latent and the manifest: to be sick was to feel unwell. Across the Enlightenment the two steadily begin parting ways, but the seismic shift occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century, with the development of X-rays and microbiology, technologies that broke the old alliance between eye and world by making it possible to see the invisible vectors and lesions of disease. Like Descartes, the pioneers of these technological developments laid bare the chasm between experience and reality: increasingly disease was something that could exist in the body without erupting into consciousness.

In industrialized countries over the last century and half, developments in medicine, sanitation, and hygiene mean that the landscape of death has been transformed beyond recognition. For 100 years between 1750 and 1850, U.K. life expectancy hovered at around 40. Across the same span, between 1850 and 1950, it rose from 40 to 68, reaching 81 by 2020. In 1908 a third of deaths were in under-fives; today that figure is less than one in a 100. In 1908 fewer than one person in 10 would live to 75; today fewer than one in three will die before reaching that age.

Changes with regards to who is dying have been accompanied and abetted by changes to how people are dying. In 1908 infectious disease accounted for 20 percent of deaths; today (with a brief anomaly in 2020–21) it accounts for 7 percent. Across the same period, deaths caused by chronic, progressive diseases have steadily increased. In 1908 cancer was responsible for around one death in 20. Death no longer bursts in rudely on the scene of life; it advances slowly, tactfully, governed by a set of recognizable customs.

One effect of all this has been to assign a new role to the notion of “awareness.” In 1907 the surgeon and early cancer activist Charles Childe published The Control of a Scourge, Or How Cancer Is Curable, addressed to a general readership. In it he warns, “You measure your disease by the amount of suffering it causes you, a natural but ghastly error.” This means that cancer’s innocent victims are often “quite naturally lulled by the entire absence of symptoms into a sense of security.”

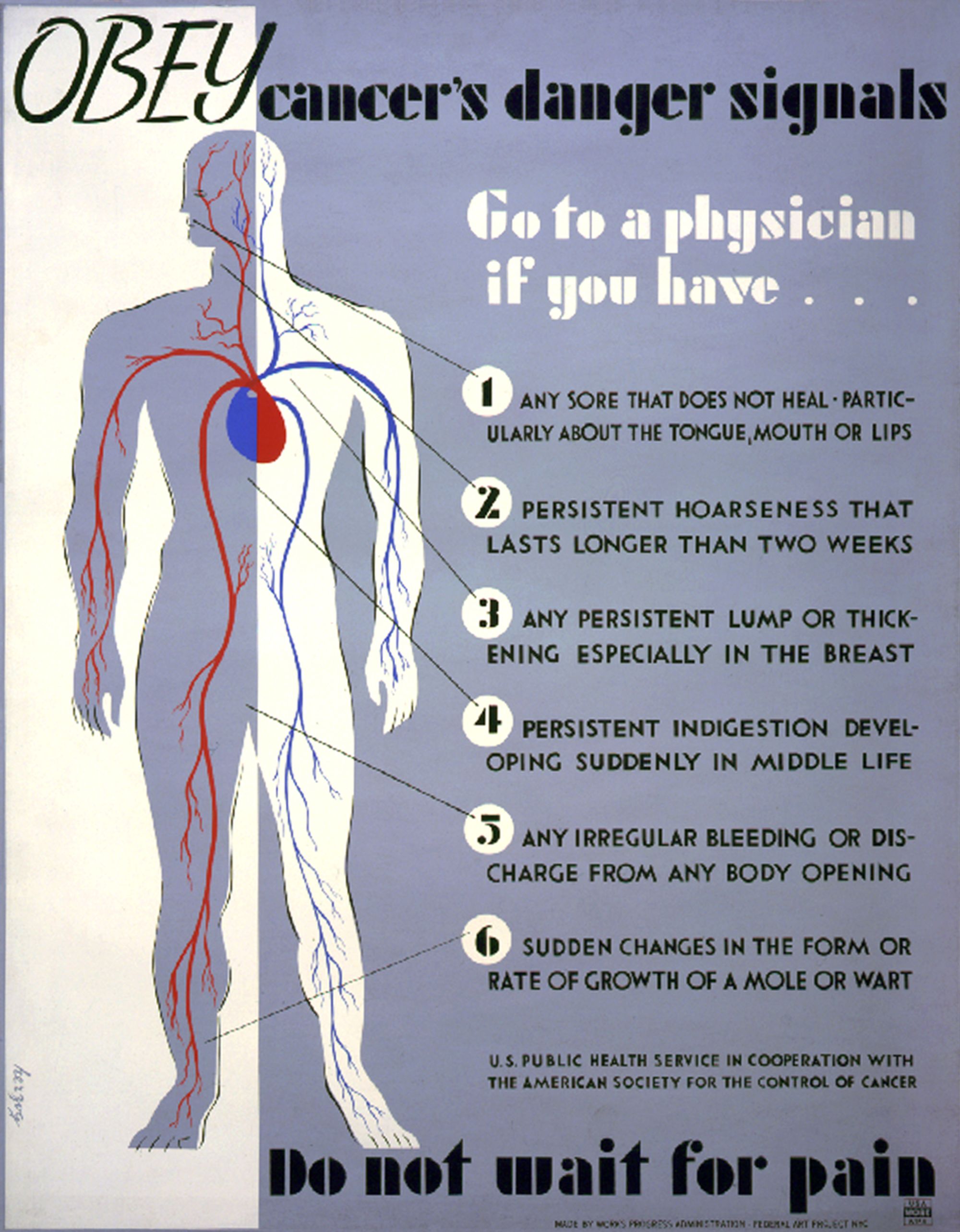

In the decades that followed, innocence would become one of the greatest threats to a person’s physical well-being. Starting in the 1930s, cancers that respond better to treatment before they have become very advanced—at a period during which any manifestations are discreet and quotidian—became a frequent topic of public information campaigns, aided by the rise of mass media. In the United States, the American Society for the Control of Cancer (the forerunner of the American Cancer Society) delivered the message that “Delay Kills!” Between 1936 and 1948 a “Women’s Field Army,” kitted out in khaki, informed the public about the value of smear tests, clinical and self-performed breast exams, and practicing vigilance toward early warning signs. In this “fight,” the Society deployed the weapons of a growing publicity industry: a WWII–era poster claimed that more people died each fortnight from a delayed cancer diagnosis than had died at Pearl Harbor.

A poster designed by Harry Herzog in the late 1930s.

Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsIn the decades since then, awareness campaigns have become commonplace. A few years ago I remember seeing posters around London warning “You can’t always see the signs” and encouraging people to check their stools for early signs of bowel cancer. These sorts of campaigns publicize the gap between subjective experience and organic reality: between how well you might feel and how sick you might be.

In this gap there is also a lot of money to be made. Since the late 1990s, websites such as WebMD and Healthline have grown into multimillion-dollar businesses by disseminating lists of early warning signs. “Did you know your nails can reveal clues to your overall health?” begins a typical article on WebMD. These articles tend to emphasize the arbitrariness of the relationship between signifier and signified: “A touch of white here, a rosy tinge there, or some rippling or bumps may be a sign of disease in the body. Problems in the liver, lungs, and heart can show up in your nails. Keep reading to learn what secrets your nails might reveal.” All this makes for pretty compelling copy, at least for the right sort of reader, which is obviously important for a business model that works by monetizing attention. The success of these companies indicates a shift in reading habits: where in the twentieth century health organizations used the tools of the advertising industry to publicize health risks, today private companies publicize health risks to sell consumer products.

In The Semiotic Challenge Roland Barthes reminds us that the word semiology originally applied to the reading not of literature but of the first and most perplexing text: the human body. These campaigns and articles are an exercise in practical criticism. They train people to be suspicious readers of their bodies. To be truly healthy, one must be more critical with regard to one’s experience of subjective well-being. A sunken nail bed? A headache? A sore? How long has this mild cough been going on? Did I always become so bloated after dinner? Don’t my gums bleed each time I brush my teeth?

Under contemporary conditions, the ideal of perfect health becomes something of a self-contradicting enterprise, since the only way it can be ensured is through a practice of conscious scrutiny that is incompatible with any holistic ideal. In the words of Wendell Berry:

From our constant and increasing concerns about health, you can tell how seriously diseased we are. Health, as we may remember from at least some of the days of our youth, is at once wholeness and a kind of unconsciousness. Disease (dis-ease), on the contrary, makes us conscious not only of the state of our health but of the division of our bodies and our world into parts.

Perhaps this is really what Freud meant when he said that hypochondria exposes the limits of our knowledge. Not an absence of knowledge, a gap that could be filled with new information, but a more categorical deficiency: the failure of knowledge to ever bring about the states of health, happiness, or even certainty which we prefer.

Hence the dialectical traps in which hypochondriacs are liable to ensnare themselves: the hypochondriac wants to feel healthy, vibrant, alive, yet in their desire to be certain of these things, they constantly find themselves feeling the opposite.

“Ours is an age which consciously pursues health, and yet only believes in the reality of sickness,” writes Susan Sontag. Health has become elusive in a society in which people are encouraged to scrutinize all aspects of their mental and bodily well-being: today being well means forever wondering just how “well” one really is. ♦

Adapted from Hypochondria by Will Rees. Reprinted by permission of Coach House Books. Copyright © 2025 by Will Rees.

Subscribe to Broadcast