Becoming Bernie

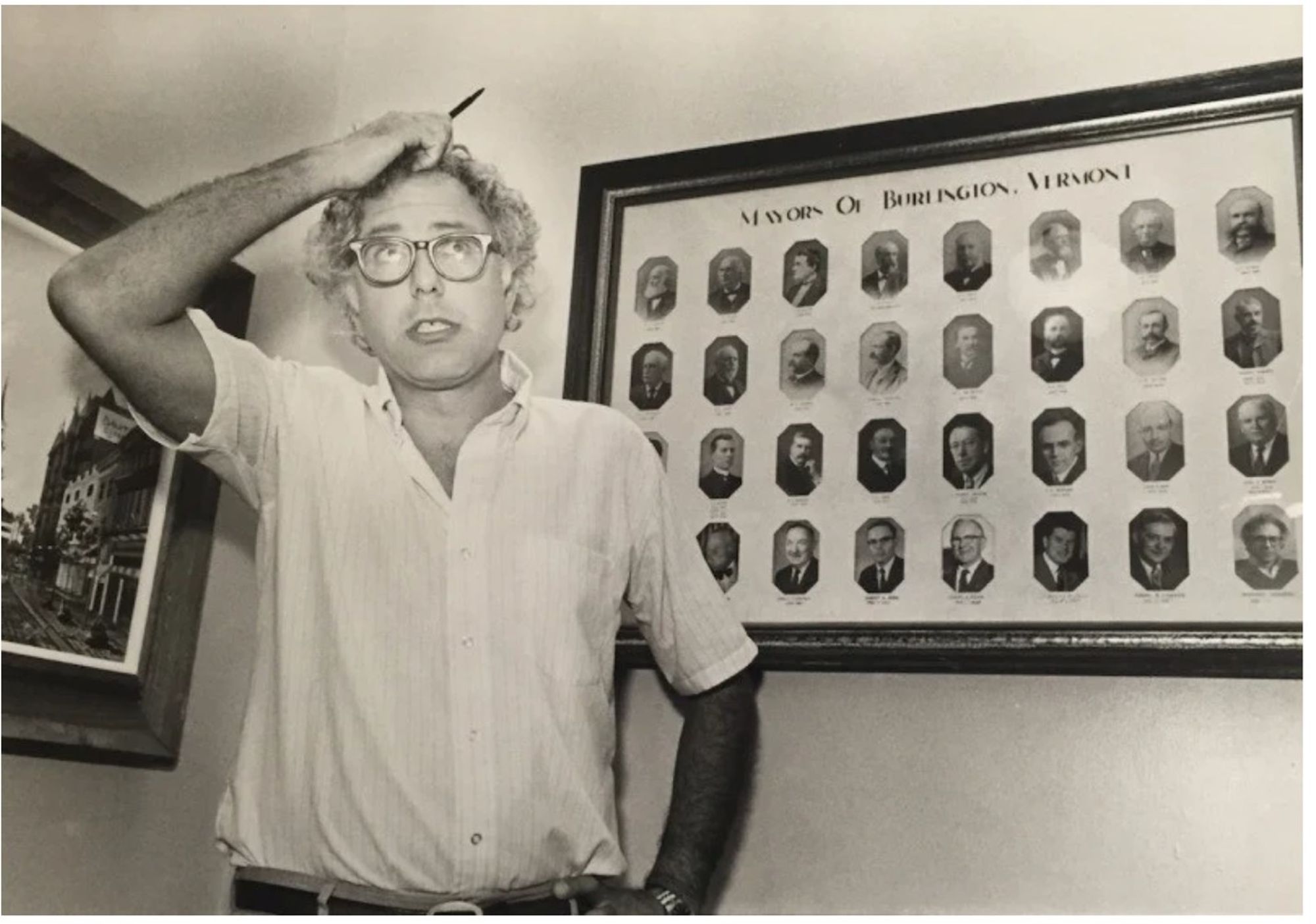

Bernie Sanders, 1981.

Photo: Jym WilsonOnce, in Midtown Manhattan, you could visit a shop with a sign that read, simply, VERMONT. Its display windows presented seasonal dioramas. Evenings, the ebullient marquee of Radio City Music Hall shouted out in neon. But Vermont, its cozy neighbor, had gone to bed early. Vermont was dark and silent.

Inside Vermont, the air smelled of woodsmoke, cider, and maple syrup. Vermont boasted that it sold nothing at all, except “the virtues of Vermont.”

But Vermont’s “virtues” were in fact for sale. In the winter of 1954, the shop window was taken over by a large three-dimensional map of the state, with colored bulbs attached where the ski areas were located. It looked like a game show prop. The bulbs shone red, yellow, or green, depending on how much snow had fallen in the real Vermont, far from Midtown. Passing cars slowed as their drivers squinted to make out the map.

Cabbies felt “despair” at driving by, according to The New York Times; their fares showed a tendency to cut short their trips, hop out, and study the display. The windows became one of the big city’s minor attractions. “There is no official count on the ‘window watchers,’” the Times reported, “but they are believed to number in the thousands.”

Inside Manhattan’s Vermont, a staff of Vermonters, mostly young women, greeted visitors, handed out brochures, and answered the phones. Winter was the busiest season. “Between 1,000 and 1,500 queries a week are received about snow conditions,” the Times reported. Many young men stopped in just to talk with these delightful, helpful women, who tended their serene island in a sea of noise and traffic.

“Vermont in New York: An Invitation!” read the full-page ad in Vermont Life magazine. “Drop in and visit about our favorite State with Vermonter Mary Jean Ogden.” “Visit about” was a nice touch: a Yankee speech artifact, suggesting a whole world of front porches and shade trees, and wholesome nontransactional encounters, free of the taint of money.

Vermont in New York, 1954. Vermont Life Magazine.

Courtesy of Penguin Random HouseOutside it was Midtown at mid-century, the world that the poet Frank O’Hara captured on his frantic lunch hour walks: workmen fed “their dirty glistening torsos” between parked cabs, while on “the avenue” women’s skirts could be seen “flipping / above heels” and blowing “above grates.”

Inside, it was another kind of poem: Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” or “An Old Man’s Winter Night,” with the despair erased, leaving only the ambience: the “snow upon the roof,” the “icicles along the wall.”

*

In the fall of that year, 19-year-old Larry Sanders took his little brother, Bernard, then 13, on the subway from their home in Midwood, Brooklyn, to Midtown Manhattan, a 45-minute trip, and visited “Vermont”: the Vermont Information Center.

They were not skiers. It might have been an accident: the shop was just to the right of the subway exit. But in 1954, a minor cultural draft blew down from Vermont. Everyone had heard “Moonlight in Vermont,” the popular song, beloved of crooners, each verse a woodsy haiku. Hitchcock’s The Trouble with Harry filmed that fall in the village of Craftsbury, where the foliage stole the spotlight from the cadaver. And Bing Crosby’s White Christmas, the remake of Holiday Inn minus the blackface, now set in a Vermont inn, premiered in November of that year.

Though there were bins of apples and little samplers of maple syrup on offer, the Sanders boys brought a different kind of souvenir back home to Midwood that day. A wire rack presented fliers for “Vermont land,” Bernie Sanders recalled in 2015. “We picked up the brochures and we saw farms were for sale.”

“It sounds like a made-up story,” Larry Sanders told me in the first of our interviews, “but it really happened.” On the subway home, Larry and Bernie pored over photos of “farm after farm, pages of farms.” The land was beautiful—but more importantly, “it was cheap.” “Cheapness,” frugality, thrift: these concepts come up over and over as we follow Bernie Sanders’s rise. They were yoked early to the idea of the state of Vermont.

There is something funny about two lanky Brooklyn teenagers discussing real estate with the reputable ladies of the Vermont Information Center. But the boys had been primed by attending the Ten Mile River Scout Camp, in Narrowsburg, New York, on the Pennsylvania border: a wild, wooded, “stunning place,” according to Larry.

“Bernard loved the countryside,” Larry explained. Vermont, he said, was “a fantasy—but an important fantasy.”

*

Larry Sanders, whose resemblance to his brother is strong but not uncanny—he is not Larry David—is the keeper of the family’s stories. Bernie has made a stand against the politics of folksy charm and personal anecdote, ever since his first races in the early 1970s. In their place he has developed a counter-charisma, an orneriness that in old age makes him seem a flinty, Yankee figure. Bernie’s cantankerousness has been very easy to sentimentalize, especially for the young. But it scalded and confused many throughout his political rise.

“The usual path is to begin with biography,” Tad Devine, a Bernie aide, told The New York Observer in 2015. “I don’t see us going there.” While Larry very naturally faces backward, Bernie has always barreled ahead. He will not, or perhaps cannot, look back; but he is shaped thoroughly by the braided economic, medical, and emotional traumas of the first little economy he saw up close, that of his childhood home.

The elder Sanders brother has lived mostly in England since 1969, where he is now retired as a Green Party official. Many Americans met him for the first time on the night of July 26, 2016, when, as a delegate for Democrats Abroad, Larry nominated Bernie for president of the United States. The clip can be found easily online: “I want to bring before this convention the names of our parents, Eli Sanders and Dorothy Glassberg Sanders,” Larry Sanders begins, his voice breaking and tears welling. “They did not have easy lives, and they died young. They would be immensely proud of their son and his accomplishments. They loved him very much. They loved the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt, and would be especially proud that Bernard is renewing that vision.”

Larry was weeping by then. Bernie had lashed himself to the mast as usual, but soon his own tears began. (I don’t believe Bernie had ever cried publicly before that night.) “It was a hectic household,” Larry told me. “My mother had a very strong temper.” Dorothy Glassberg was born on the Lower East Side in 1912. Home movies from the 1940s show a handsome, stylish woman, at home in a swagger coat and pillbox hat. She waves baby Bernie’s hand to the camera, broadly smiling.

But her “hectic household”—three and a half rooms in a tenement—reminded her perhaps too much of her childhood. “She wanted a house,” Larry said; she “yearned for status in the synagogue” and in the surrounding community, which came only with having a home where a woman could reciprocate her neighbors’ hospitality.

The apartment at 1525 East 26th Street had a bedroom, a bathroom, a kitchen/living room, and a “half room, a widened part of the hall,” which, according to Larry, served as a second bedroom. When they were both living at home, Larry and Bernie alternated, the one sleeping in the makeshift bedroom, the other on the living room couch. “They threw a bathroom in as well,” Bernie once wrote. “My memory of that one time a fish actually came up through a toilet.” The apartment “was incredibly cramped,” Larry told me. “Not only didn’t we have a room of our own, we didn’t have a room together.”

In the main room, there was a bookshelf with perhaps 20 books (including a eugenics textbook whose anatomical illustrations were “very popular” with the boys), a radio, and, from 1948 or so on, a TV. The apartment offered “no privacy at all”—no place, Larry added solemnly, that Bernie and Larry “could decorate.”

With space indoors scarce, Larry said, “the street was our second home.” The rule on the pickup basketball courts was “Make it, take it”—you score a basket, you get the ball back—a brutal capitalistic model for competition, and one that Bernie practiced in his political life, whatever his ideological commitment to the fair distribution of wealth. “We played baseball, softball, punchball, stickball, stoopball, roller hockey, variants of American football, touch football, touch tackle, basketball, marbles,” Larry said. “It was a very good way to grow up.” Bernie, he added, “might not entirely agree.”

*

In some marriages, the party that insists on a narrower world automatically wins, though the victory is costly. Dorothy Sanders apparently wanted a broader life.

But three and a half rooms were quite enough for Eli Sanders, who had emigrated to New York from Słopnice, Poland, in 1921, at the age of sixteen. His family in the old country sometimes went without food. “My father’s imagination, his life story, was survival,” Larry explained. Anything extra was trivial. Larry remembers his father watching a TV show about middle-class “psychological distress” and shaking his head. “But they’ve got plenty of money,” Eli Sanders muttered. “They’ve got everything they need.” Eli had an existential sense of life, drawn in part from his subsistence childhood, and augmented by the news dawning from Europe. Leafing through an old family photograph album, Eli Sanders pointed to one relative after another who’d been killed or lost— “gobbled up,” as Larry put it, in the Holocaust.

Eli Sanders was a commissioned paint salesman for the Keystone Paint and Varnish Company. He traveled up and down Long Island for his work and, according to Larry, “probably stopped at every diner along the way.” In the home movies I have seen, he is a paunchy man, and ill at ease throwing a ball to his sons. But he had a ready smile and a sweet, gregarious manner. Larry suggests that he spent a lot of his days chatting with his clients, which might have cut into his commissions. In Eli’s mind, the family had arrived. In his wife’s view, they had stalled out just on the other side of poverty.

In a story both Bernie and Larry tell, their father saw Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman late in its Broadway run and wept for weeks after whenever he thought of Willy Loman, its thwarted protagonist. “He was devastated by it,” Larry told me. The play brought home to Eli how close his family had always been to economic collapse. Like many Americans in their precarious position, the Sanders family lived near despair. “The bottom could fall out,” as Larry put it. You might be tempted to conclude, as Willy Loman did, that “a man is worth more dead than alive.”

Bernie (left) with mother Dorothy Sanders and Larry.

Courtesy of the Sanders Institute and Penguin Random HouseSo Eli and Dorothy Sanders fought. They fought because they were frightened. The fights were unbearable to the boys, since, as they could plainly see, their parents were closely attached, and loved each other very much.

“My father’s thing was, you were spending too much,” Larry explained, “and my mother’s was, you’re not earning enough money.” This went round and round and “destroyed what they had.” These were “arguments that seared through a little boy’s brain, never to be forgotten,” Bernie Sanders wrote in Our Revolution.

Once, in the 1980s, I saw Bernie shopping at a department store in Burlington, now long gone, called Magrams. He pointed tentatively at the shirt racks, as though trying to make contact with an alien being. A few minutes later, from a second-floor window, I watched him exit the store and storm down Church Street toward city hall, empty-handed. I’ve always told it as a funny story; but when you hear the brothers discuss the anxiety that money caused them as children, it seems not funny at all.

In Our Revolution, Bernie describes an errand he ran for his mother to buy groceries. “I went to the wrong store,” he wrote. “I went to the small shop a few blocks away, rather than the Waldbaum’s grocery store on Nostrand Avenue. I paid more than I should have. When I returned and my mother realized what I had done, the screaming was horrible.”

“The worst of it,” Larry told me, still agonizing 70 years later, “wasn’t what we didn’t have. It was the tensions. The arguments.”

*

I drove out to Midwood from the Upper West Side one beautiful April afternoon, across Central Park and down FDR Drive, over the Brooklyn Bridge, through a tangle of on- and off-ramps and, at last, out Ocean Avenue. How could it all work so well, said I, a Vermonter, to myself; every bolt and rivet holding as I sped through the balletic chaos of New York’s built environment?

The temperature fell several degrees as I neared Sanders’s childhood home in a mid-rise tenement on the corner of 26th Street and Kings Highway. Coney Island and Brighton Beach are nearby. You sense the beach in Midwood, in the flat, shadowless glare of the light, and in the gusts of fog that blow across the playgrounds and parks.

The food critic Mimi Sheraton, who grew up in Midwood, described an April day there in 1946. It matched what I saw nearly perfectly: mid-rise brick apartments trellised with black metal fire escapes on the avenues, and “builders’ houses, usually duplicated three or four in a row” on the side streets, “brick and stucco affairs.” Bright yellow forsythia blazed in many of those small backyards, just as she had described during this same calendar week in 1946.

It was, and is, a middle-class neighborhood with the feeling of an inner suburb. In Bernie’s day, it was an enclave of rapidly assimilating Jews within the larger neighborhood of Flatbush. Now the place has been carved out from Flatbush, and attracts a wide array of immigrant families, but especially Orthodox Jews of Russian descent. The day I was there was during Passover; a bunch of guys selling homemade matzoh on the street asked me if I was Jewish.

“Nope, Catholic,” I replied, and they waved me off with a chuckle. 1525 East 26th Street, a six-story, yellow-brick tenement, stands apart from the cheerful single-family homes. Many families in the neighborhood began their lives as renters in buildings like this one, aspiring to purchase one of the little houses at its ankles. Bernie’s parents dreamed of making that leap, but it never came. In Midwood, in the 1940s and ’50s, to own a “private house,” as Bernie’s parents called them, meant you were seen, your family was acknowledged, you were part of the neighborhood’s fabric. Once inside 1525 East 26th Street, though, you vanished.

I walked down 26th Street to James Madison High School. There they remember Bernie Sanders: in the entry hall, just beyond the metal detectors and security guards, is the Madison High School “Wall of Distinction.” Bernie Sanders ’59 is one in from the lower left corner, next to Beverly Stoll Pepper, the sculptor, who is the mother of the poet and my friend Jorie Graham. They are in distinguished company. Ruth Bader Ginsberg ’50 shares the top row with the famed environmentalist Barry Commoner ’33, Charles Schumer ’67, and Stanley H. Kaplan ’35, the founder of the test prep company. Working down the grid, we find Carole Klein King ’58, several professional athletes, four Nobel laureates, and Judith Blum Sheindlin ’60— “Judge Judy.” The roster of graduates is “more distinguished than Eton’s,” Larry Sanders told me, with a laugh.

What was the secret to the school’s success? “It was one of those schools where you felt what the old world was,” Jorie Graham told me. “The permission to get an education was an astounding gift because so many had died in Europe.”

Bernie entered Madison in the fall of 1954, around the time he and Larry picked up their Vermont brochures. Classmates recall a quiet and serious boy, not terribly political but, as his brother put it, “aware” of politics. “Jewish boys growing up in that time couldn’t but be aware just how important politics is,” Larry said. “It’s a matter of life and death.” Sanders eventually ran for student body president, finishing last among three candidates, on a platform to aid orphans of the Korean War.

But sports, and not politics, offered Bernie his first method of channeling his intensity. In a setback, Bernie, always a great pickup player on Brooklyn’s “Make it, take it” outdoor courts, was cut from the varsity basketball team. He was a “tremendous player,” Larry said. I confirmed that I had seen his game on the pickup courts in Burlington: strong ball handler, solid outside game, and, always, a complete, transforming intensity. Madison “wasn’t the skyscraper squad,” according to Larry, but they did have one of the “top-ranked teams in the city.” If only he’d been “an inch or two taller.” (Bernie stands around six feet one.)

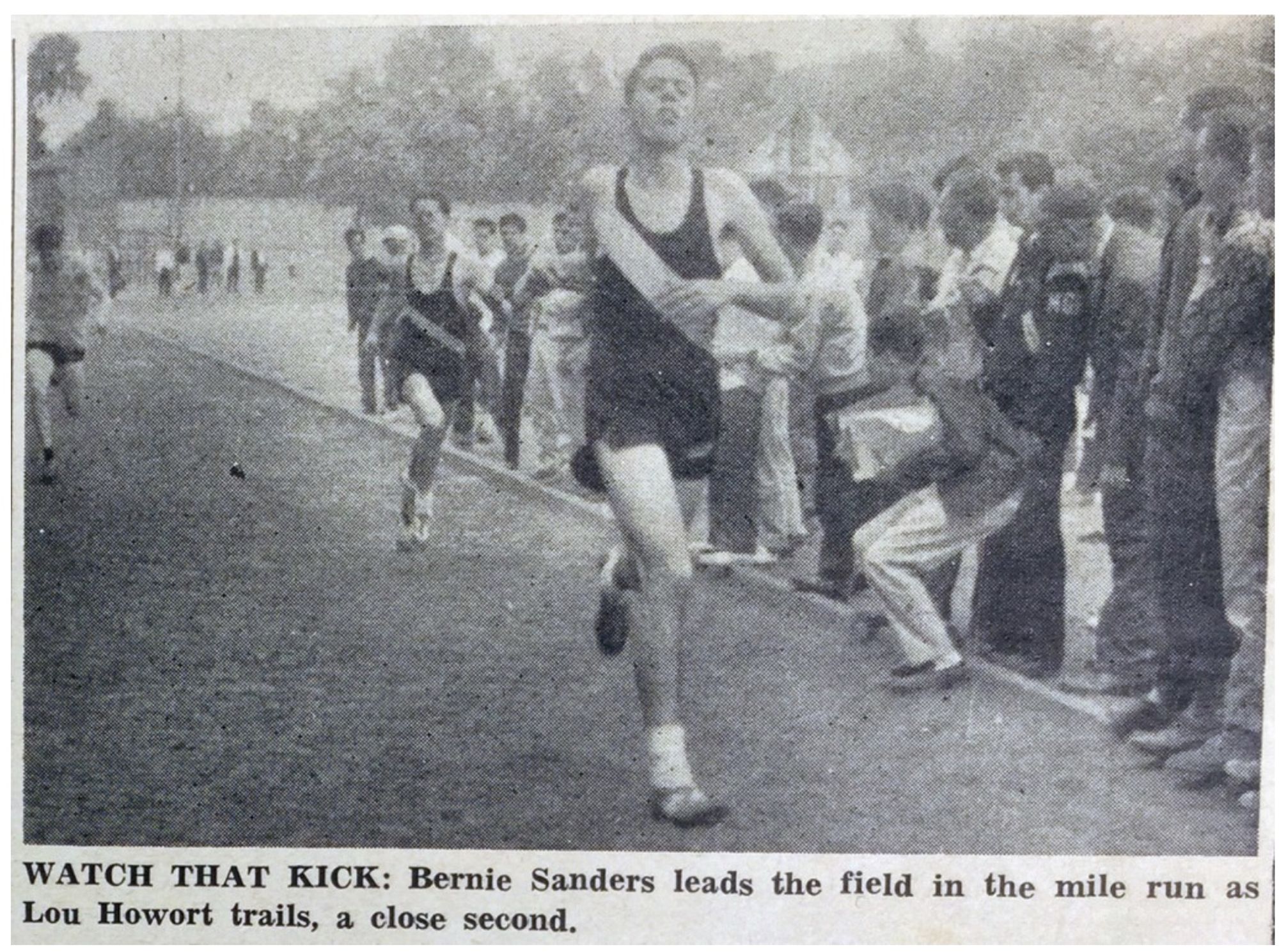

Sanders became a standout athlete in track and cross-country, and eventually captained both teams. It baffled me, when Bernie sought to introduce himself to voters in his two presidential runs, that he did not capitalize more on his astonishing high school running career; the ads write themselves. Bernie’s best mile was 4:37, which earned him third place in New York City. That’s blazing fast, when you consider he ran in it on a cinder track, wearing primitive spikes. Even more impressive, to Larry, was his brother’s cross-country prowess. The course, way uptown in Van Cortlandt Park, “was always amazingly muddy,” he recalled. The races showed Bernie’s “tremendous stamina and dedication.”

Sanders finishing strong.

Courtesy of Lou Howart, Madison High School, and Penguin Random HousePractices were just getting underway when I left Madison High that afternoon, April 15, 2022; the courts and fields were filling up with students. Other kids were walking home alone, glued to their phones, or flirting in small, raucous groups. There is really nothing on earth like a high school dismissal, I thought to myself. The teachers and administrators streaming out looked almost as happy as their students, and took me for one of their own.

Theodore Hamm’s Bernie’s Brooklyn describes the strong web of public projects from which the Sanders family benefited as a result of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which Larry Sanders also invoked at the 2016 convention: it brought baskets of federal money to New York City, expertly distributed by Roosevelt’s local ally, Mayor Fiorello—the name means “little flower”—LaGuardia, who stood only five feet two. Their apartment was rent controlled; Larry guessed the rent was about “50 bucks a month,” perhaps a tenth of his father’s pay. Beginning in the 1930s, there were new roads, schools, and swimming pools, and a new campus for Brooklyn College, where Dorothy Sanders eventually organized the Hillel seder every spring.

It was “an environment where New Deal politics were quite normal,” Larry said in a 2015 interview with Vermont’s Seven Days. “It was widely understood that government could do good things.”

And yet, anybody who has hefted Robert Caro’s The Power Broker knows that these anonymized government works had a dark side. Larry Sanders recalls the new public library, which replaced a makeshift space attached to the fire station, a romantic, enchanting hideaway for the neighborhood’s kids. The update was a modern, spic-and-span building.

Life in the family apartment seemed alternately clenched and explosive. Outside, though, Brooklyn appeared to be blossoming and changing. Government was indeed doing “good things”: Larry points to “a comfortable environment” where the “streets were free and easy and safe.” But ordinary families had no say in their neighborhood’s transformation. Some were relocated by eminent domain if their buildings blocked construction of an exit ramp. Old homes were now mere feet from the cascading traffic; fragrant blocks were turned into dank, toxic canyons by the new highways.

And none of these grand improvements had eased the worries of Bernie’s parents in their small apartment, or altered their wearying daily pattern.

“Nobody would have chosen the new library,” Larry Sanders told me. And the concrete of the new city playground was “very destructive to arms and legs.” It was mystifying when a new building or playground suddenly materialized where another, beloved structure had been. Who made these decisions? The Midwood families themselves had played no role.

I told Larry that it reminded me of seeing Bernie for the first time on my front porch, when I was nine, as he was priming people for votes. It was a scene that played out over and over in his eight years as mayor. You’d hear about a bond issue coming before the city for some important public works project. Soon, Bernie or one of his disheveled volunteers was out on the street, or in the parks, or at your front door, looking for your support. The skinned knees kids got on those Brooklyn playgrounds stayed with him: a visitor to Burlington, Bernie once boasted, would visit its parks and say, “This is a people’s country club. You have tennis, you have swimming, you have softball.”

“Inform your parents,” Bernie would exclaim, finishing his pitch to a group of disaffected 14-year-olds.

*

“The train stops somewhere in Brooklyn,” Bernie Sanders wrote in 1969, in the Vermont Freeman.

A crowd gets out, someone walks a few blocks into a 3 room apartment, family, dinner, arguments TV and sleep. Eight-thirty the next morning the train is back on 14th street.

The years come and go, suicide, nervous breakdown, cancer, sexual deadness, heart attack, alcoholism, senility at 50. Slow, death, fast death. DEATH.

The piece was published under the headline “The Revolution Is Life Versus Death.” It provides a quick montage of Bernie’s childhood, inflected by his radical politics in their embryonic, late-1960s form, heavily influenced by his reading of Wilhelm Reich.

While Larry weeps when he shares his childhood stories, Bernie is mostly silent about those years. Larry told me that his brother sometimes accuses him of “minimizing” the degradations of the household. But Bernie’s politics clearly began at his parents’ breakfast table. Their scorching arguments showed him the emotional and psychological costs of being underpaid. If his hard work didn’t pay Eli Sanders enough to support their family’s modest needs, who was being paid for his father’s labor? Where did the money go? Eli and Dorothy Sanders turned those frustrations against each other. “The money question to me has always been very deep and emotional,” Bernie wrote in the Freeman. As Larry told me, it “ruined” the bond their parents had.

All through their childhoods, the Sanders boys carried the sense that the “bottom could fall out” of their household, as Larry put it. Dorothy and Eli Sanders saw their sons leave home; and then, almost instantly, the bottom did, in fact, fall out. The strain of raising their small family had weakened and sickened them both. Throughout the 1950s, Dorothy Sanders had treated her congenital heart condition with rest and whatever remedies the family could afford, all the while rooting for the rapid advances in open-heart surgery, widely reported in the papers, that would repair her mitral valve and save her life. But this costly, risky surgery would require more than a financial miracle for the hard-pressed Sanders household: Dorothy Sanders had a blood type of AB negative, the rarest variety. A typical open-heart procedure required at least 25 pints of fresh blood; banked blood loses oxygen in storage and could not be used.

“19 ‘Blue-Bloods’ Aid Boro Woman Battle for Life,” read the punning headline in the March 14, 1960, Brooklyn Daily. After her condition dramatically worsened, Dorothy Sanders was rushed to a charity facility, Deborah Hospital in New Jersey, where she awaited a blood donation from the National Rare Blood Club, a Park Avenue philanthropy. The procedure would stand her “in good stead in her efforts to regain her health,” according to the paper. But on March 25, Dorothy Sanders succumbed to surgical complications at the age of 47. Bernie, a freshman at Brooklyn College, had coordinated her care and sat by her hospital bed: he was now “destroyed” and “wanted to get away from Brooklyn,” his brother said. The experience was Bernie’s first with doctors and hospitals, and it left the lasting impression that whether a person lived or died in our medical system was a function, not of the severity of a patient’s condition, but of her ability to pay. Of all the stark economic lessons Bernie learned in the family, the last days of his mother’s life struck him most powerfully.

Now alone in a silent, darkened apartment, Bernie’s father “completely fell apart” after his wife’s death, and died just two years later under tragic and strange circumstances, behind the wheel of his car, evidently of a heart attack. From news reports at the time, it can be surmised that he had tried to drive himself from Midwood to the emergency room of New York–Presbyterian Hospital in Manhattan. Eli Sanders, just 58, was found slumped over his steering wheel, having crashed his car into a bank of construction barriers outside the hospital entrance.

*

There is a clip that can be found online from the public access TV show that Bernie hosted in Vermont in the 1980s, when he was Burlington’s mayor. He’s come to Cathedral Square, the mid-rise senior living facility in downtown Burlington where, as it happens, my uncle Esau lived out his final years. Though the apartments are for elderly people on fixed incomes, many have million-dollar views across Lake Champlain. A few times I went along with my mother to bring Uncle Esau a bag of McDonald’s for his dinner. I remember baseball on Channel 11 from New York City, on Uncle Esau’s dinky TV; and behind it, ravishing purples and oranges of the sunset as it broke apart on the peaks of the Adirondacks.

Mayor Sanders and his predecessors, 1984.

Courtesy of Burlington Free Press and Penguin Random HouseBernie is at Cathedral Square to connect with the elderly. He describes a city plan to bring seniors relief from rising taxes, then checks in on whether progress has been made on wiring Cathedral Square for cable TV. The room, I can see, is full of immigrants and children of immigrants, including many likely displaced from Burlington’s Little Italy, the thriving neighborhood razed by the city during the 1960s, and located on the very spot where Cathedral Square and the Episcopal Cathedral Church of St. Paul were later built.

The meeting is both funny and poignant. Sanders does not have a special personality reserved for the elderly. Sitting on the edge of a folding table, he spars with the old men and women, pushes back, cross-examines, shows a bit of exasperation and impatience. There is never a note of condescension.

“See, the beauty of the program is, it’s called ‘bulk billing,’” Sanders explains. Since you likely have heard Bernie’s voice, you know how much of Midwood, Brooklyn, enters the room with a word like beauty.

A woman interrupts. By her accent I can tell she is from St. Joseph’s Parish and grew up in Ward 3, the Old North End. She and Sanders are two working-class people from ostensibly different worlds. But they recognize each other. She begins: “It is my understanding from our meeting that they had to have a good number, not 100 percent, in order to get the low rate, otherwise we would have to pay the $10.50— ”

“Nope!” Sanders interjects.

“—let’s say like 30 people signed up— ”

“Nope! Absolutely not! Is that what they told you?”

Grumbles, nods of assent all around; Bernie, sounding flabbergasted, makes a note, and promises to follow up. The woman seems unconvinced and irritated.

The year is 1987: if they’d lived, Eli Sanders would have been 83, Dorothy Sanders, 75. ♦

Excerpted from BERNIE FOR BURLINGTON: THE RISE OF THE PEOPLE'S POLITICIAN by Dan Chiasson. Published by Alfred A. Knopf. Copyright © 2026 by Dan Chiasson. All rights reserved.

Audio excerpted with permission of Penguin Random House Audio from BERNIE FOR BURLINGTON by Dan Chiasson, excerpt read by Gabriel Vaughan. Dan Chiasson ℗ 2026 Penguin Random House, LLC. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to Broadcast