In Defense of Useful Art

Can artwork be useful, can it be productive, and can it be a work of activism? We can look to Tania Bruguera’s project, Arte Útil, which explores artwork that is wholly utilitarian, or the critical design theory of Fiona Raby and Anthony Dunn, which imagines product design separated from capitalism. Both of these theories challenge that artwork can be productive, as well as provocative. As an artist and researcher, my work intersects across a variety of points of human rights, social justice, art, design and research and is inspired by critical design and Arte Útil. My artistic output can take the shape of a white paper, a civil society action, a design to solve a solution, a social justice workshop, an article, or an artwork artifact. However, I consider all of these outputs to be a form of my artistic practice and my research practice. Much like the work of Arte Útil, artwork can be functional and useful, if made by an artist. A white paper can be a legible part of an artistic practice, even with no clear artistic artifact object tied to it.

In late May after the US erupted in protests for Black Lives Matter and after George Floyd’s death, a number of curators and critics remarked on social networks about tech artists (read: white and male) and their roles in unpacking technology, injustice, and activism. Over email, the curator and writer, Nora Khan discussed artistic practices during moments of cultural upheaval, protest and human rights, specifically right now during Black Lives Matters protests and where art fits into this space. Khan wrote, “During this period of protest, coupled with unprecedented expansion of surveillance and predictive technologies activated around us, it is hard not to think of the role of many technology-based artists. Many have made long careers of critiquing surveillance, the police and carceral state, by unveiling its nodes and mechanisms. When does a lauded critique of surveillance capitalism—as an artwork, in the form of an artifact—serve to reify and keep power intact? How might critical technological work be called on, as this moment, to do more? Coded, designed work has that capacity. Hybrid research practices can explain and expose the logics of racial capitalism, but under the auspices of artistic collaboration, can enact critique, make an argument through process, through a built system."

This idea of usefulness, and interdisciplinary work, is key. Khan highlights the strengths of work stretching across domains, making art a necessary trojan horse to discuss useful change. This is where I turn to the work of American Artist, Francis Tseng, Joanna Moll, Adam Harvey, Mimi Onuoha, Forensic Architecture and others. These artists are pulling from research or investigatory based practices and with work that manifests into a variety of outputs, artifacts, writings and education. The practices of American Artist or the anonymous group behind ScanMap are great examples of social justice and human rights driven art, with ScanMap’s current work tracking police scanners, or American Artist’s works “I’m Blue (If I was ______ I Would Die)” and “My Blue Window”, two pieces that comment on the structure and violence of the modern police forces. These two practices function in conversation together- Artist’s work poetically comments on the police as artistic artifact, and ScanMap’s work exists in a more critical technology space- using code to create direct action and intervention and create a useful tool to document and observe the police.

Other examples of social justice, research and artistic practices are works like The Hidden Life of an Amazon User by Joanna Moll, or Adam Harvey’s VFrame research which came out of his numerous collaborations with the human rights archiving group, the Syrian Archive, or the investigative work of Forensic Architecture. One example of a research and social justice based arts practice is Mimi Onuoha’s. Onuoha’s research work on the politics and injustices of data sets have resulted in artworks like “The Library of Missing Data Sets” and the widely cited, and canonical zine, and educational tool, the People’s Guide to Ai, co-written with Diana J. Nucera. These pieces, and artists, occupy a liminal space of research, journalism, and art. These aforementioned works can be viewed solely as ‘art’ or as research, but are much more richly seen when viewed as research based artistic activist practices. While that’s a wordy description, it rings true to the intention of the works. The works aren’t just to bear witness, though that alone would be worthwhile; they question, provocate and offer a solution to a problem. This should not be viewed as a form of techno-solutionism however; the ‘solutions’ the artists provide are not meant to create an end to all other potential solutions, but serve to offer rather, temporary or open-source fixes for gaps in equity and violence created by society and are poetic witnesses of those gaps. This kind of ‘band aid’ is in a similar space where I pursue my own practice. Bandaids exist as necessary provocations or patches while with participatory design and deconstruction, artists, human rights researchers, activists, technologists, and communities can overhaul the system or destroy systems together. The togetherness and collaboration is key, though. But nonetheless, provocations within art and design can create imaginaries for new realities.

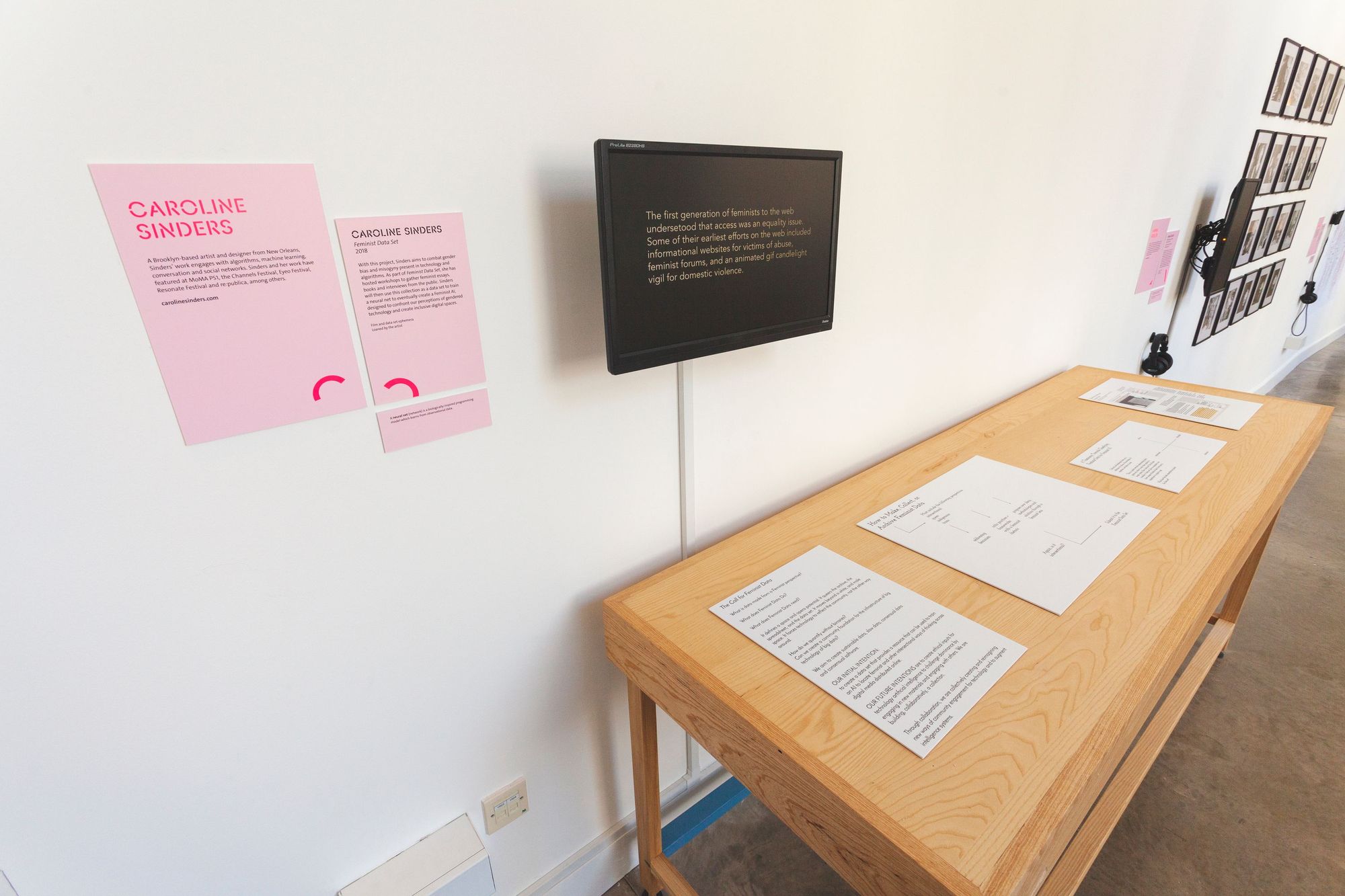

For the past few years, I’ve been looking at the impacts of artificial intelligence in society. Some of this work has taken the shape of lectures and workshops on data, surveillance, and AI, numerous articles on the harms of AI, my Feminist Data Set arts research project, and a new project recognizing human labor behind artificial intelligence systems. My current project named TRK or Technically Responsible Knowledge is an open source project that examines wage inequality and creates open source alternatives to data labeling and training in AI. TRK was funded by the Mozilla Foundation and was created with Cade Diehm, Ian Ardouin Fumat, and Rainbow Unicorn. Over 2019, I interviewed research labs, artists, startups who use Mechanical Turk style services, and microservice workers across Crowdflowr, Fiverr, and Mechanical Turk. I even became a Mechanical Turker myself for a few weeks.

TRK is an alternative, open source tool for dataset training and labeling, a time consuming but integral aspect of machine learning that must be completed in part by a human. The tool offers a wage calculator that helps visualize a livable wage to those that will then be responsible for completing the tasks. TRK is a part of the Feminist Data Set Project where I’m using intersectional feminism as a framework to investigate each part of the machine-learning pipeline for bias, inequity, and harm. As an artist who uses AI as a material to explore and make art, I was struck by how many start-ups, research labs and artists use Mechanical Turk style platforms without any thought given to the payment structure determined for workers on the network. Mechanical Turk, and similar platforms, have had well documented cases of horrendous worker related issues, such as severely under-paid contracts. In many instances even if a lab or individual is trying to price equitably, the interface of Mechanical Turk works against it.

If the machine learning pipeline is death by a thousand cuts, think of TRK as one band aid for one small cut. The project doesn’t propose a solution for all issues related to machine learning or even a major one for Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. So many issues related to machine learning are issues of a deeper more ingrained societal inequity which can only be addressed through large shifts and restructuring in society or legislation. But within that, as a designer and researcher, I try to look at what kinds of research or work can help alleviate or expose issues. TRK focuses on how, through pricing structures, platform incentives and the invisible nature of gig work, clients underprice, undervalue, and fundamentally misunderstand how tasks are handled in ‘human as a service’ platforms. This has a direct effect on the workers who fulfil tasks. Human laborers in Mechanical Turk style platforms must operate within systems that commodify them, leaving them underpaid and poorly treated. This project attempts to shed light on how payment interfaces can function to benefit the worker.

Part of the design thinking behind TRK is to examine equity and transparency within interfaces and the design of tools, and what kinds of problems tool design, UX, and UI create in technology. Inspired by the Data Sheets for Data Sets white paper TRK injects plain text information into the data set with information that includes a description of what the dataset is, and when it was made. UX or user experience design is a utilitarian intelligence, focusing on architectural layouts, usability, and user flows, but design has a politics to it—it can suppress or uplift content. Design, much like technology, isn’t neutral. As an artist, I use design as a material to confront and comment on the slickness and inequity of for-profit technologies.

Design can be an actuator for change but design alone is not an entire solution towards injustice in society and technology, design can confront a problem while acknowledging it is a part of ‘the problem.’ Design can help visualize or highlight parts of systemic injustice, but design must unpack and confront it’s role in contributing to injustice in technology. However, it’s imperative we view design as a tool, the same way we view code and programming as tools. Much like how programmers use code or programming languages as a means to create change, I leverage design in a similar way, and use it to create the same kind of space of usefulness to explore problem solving. Similarly, how anonymous programmers and artists created ScanMap to provide a solution for surveilling the police, and Everest Pipkin’s tool to blur images for people to use at protests, design can sit in a space to solve small problems that are a part of bigger spaces and issues. My approach to design thinking proposes a de-commodification of art, and situates it as a process and investigation. Artistic approaches to problems allow for collaborations that might not happen in other fields, and in this way art’s role in social justice and human rights projects ‘makes space’ for new kinds of work in a way that other fields traditionally could not let those projects exist.

Subscribe to Broadcast