Big Apple Sky Calendar: January, February, March 2026

The Pleiades star cluster, as captured by the NASA Spitzer Space Telescope, 2007.

Courtesy of NASA / JPL-CaltechIn the 1990s, astronomy professor Joe Patterson wrote and illustrated a seasonal newsletter, in the style of an old-fashioned paper zine, of astronomical highlights visible from New York City. His affable style mixed wit and history with astronomy for a completely charming, largely undiscovered cult classic: Big Apple Astronomy. For Broadcast, Joe shares current issues of Big Apple Sky Calendar, the guide to sky viewing that used to conclude his seasonal newsletter. Steal a few moments of reprieve from the city’s mayhem to take in these sights. As Oscar Wilde said, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

—Janna Levin, editor-in-chief

January

January 1

Sunrise 7:20 am EST

Sunset 4:39 pm EST

(1801) On the very first night of the nineteenth century, Giuseppe Piazzi found a slowly moving starlike object, which he assumed to be a comet (at that time, only the planets of antiquity were known). But was it a comet? Maybe not, because it showed no tail or fuzz. Only a few precise observations were obtained before it was lost in the glare of the Sun. Fortunately, a very young Carl Friedrich Gauss—now regarded as the greatest mathematician since Archimedes—became interested in how to derive an orbit from merely three observations. He successfully predicted where it would be when it emerged from the solar glare…and later studies showed that the object moved in a nearly circular orbit between Mars and Jupiter. Sort of like an actual planet!

The object was named Ceres, after the Roman god of agriculture. It was the first known asteroid, or “minor planet” (the currently favored term). There are now many thousands known, most quite small and in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Asteroid names have gone berserk. They ran out of Greek and Roman gods a long time ago. For a good time, google “funny asteroid names”—and if you actually discover an asteroid (plus solve for the orbit), you can even contribute to the madness.

Portrait of Giuseppe Piazzi, 1808.

Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute Library.An approximate true-color image of Ceres, 2015.

Courtesy of NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDA / Justin CowartJanuary 2

There was another planetary puzzle that dogged astronomers throughout the nineteenth century: the motion of Mercury. It did not exactly obey Newton’s Laws and some astronomers thought there could be another planet, close to the Sun, that was tugging slightly on Mercury. It even got a name: Vulcan (of course). On January 2, 1860, the French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier announced that he had discovered (through calculation) the orbit of Vulcan. But no one ever actually saw it. Le Verrier was wrong. There were scattered claims of seeing the silhouettes of unknown objects crossing in front of the Sun. But none were confirmed, and Mercury’s odd motion wasn’t explained until Einstein’s General Theory (in 1915) showed that the geometry of space in the near vicinity of the Sun is slightly non-Euclidean.

January 3

Earth is today at perihelion—as close as it ever gets to the Sun, just 0.983 AU from the Sun. Amid January’s deep freeze, this may be surprising. But remember that the seasons are caused not by distance, but by the tilt of the Earth’s axis. The variation in distance (0.98 AU in January, versus 1.02 AU in July) is just not enough to make a big difference.

Still, wouldn’t you expect that the maximally close Sun in January and the maximally distant Sun in July would give the northern hemisphere warmer winters and cooler summers? The opposite is true—the highest recorded temperature on Earth is 134°F (Death Valley) and the lowest is -109°F (Yakutsk, Siberia). Can you guess the reason for the extremes being reached in the North rather than the South?

View from Zabriskie Point in Death Valley, 2013.

Courtesy of Tuxyso / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0January 8

The anniversary of Galileo’s death, in 1642. Still under house arrest from the Inquisition, Galileo hung on just long enough to get his magnum opus on dynamics (Two New Sciences) smuggled out to Holland, where it could be published. On this precise date three centuries later, another adventurer in space and time was born: Stephen Hawking. Hawking showed that the two bedrock principles of twentieth-century physics—relativity and quantum theory—can actually be reconciled if black holes emit some radiation. It has never been observed, but we’re still looking!

Stephen Hawking in San Francisco in the mid-1980s.

Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsJanuary 7–10

On these four nights in 1610, Galileo turned his telescope on Jupiter… and noticed four stars which moved around Jupiter—the “Galilean satellites,” as we now call them. Or the Medicean Stars, as Galileo called them, in an effort to curry favor with his patron, Cosimo de Medici (a boy of nine). This discovery did a lot to demolish the Ptolemaic model of planetary motions. It had previously been argued: “If the Earth moves, how can it hang onto the Moon?” Well, there was Jupiter up there, obviously moving around something, and having no difficulty hanging onto its moons.

Before the discovery scene in Bertolt Brecht’s play Life of Galileo, a curtain appears with the ominous words: “January 10, 1610: Heaven Abolished.”

January 10

Last quarter Moon, rising near midnight. Also, Jupiter is at “opposition” tonight—meaning “opposite the Sun, transiting near midnight”… and therefore in a great position for telescopic observation.

January 14

The Orthodox New Year, which is New Year’s Day on the Julian calendar (as distinct from the modern calendar, which was instituted by Pope Gregory in 1582).

January 15

Sunrise 7:18 am

Sunset 4:54 pm

January 16–31

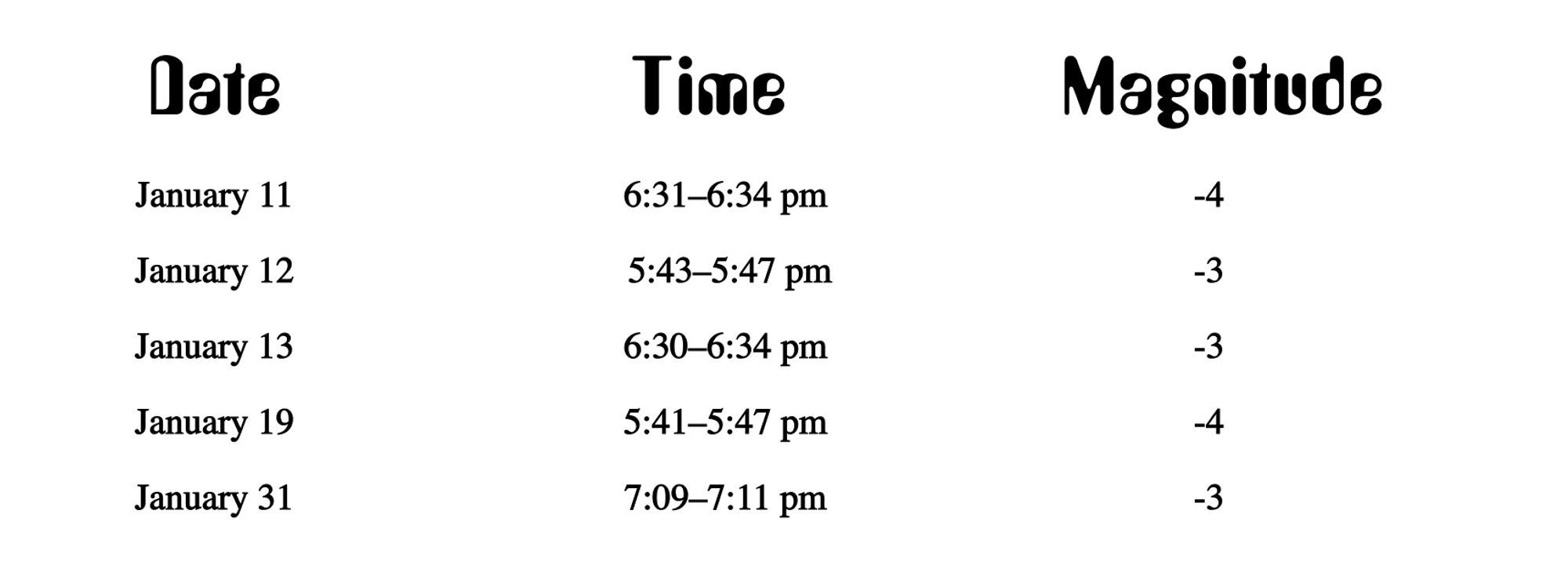

Five good overpasses of NYC (or anywhere nearby) by the ISS (International Space Station) occur this month. Here’s the schedule:

Magnitude -3 and -4 means “brighter than any star, and as bright as Venus.” For these ~five-minute apparitions, look first near the WSW horizon. It looks like a plane, except that (a) its light doesn’t flash, and (b) it disappears suddenly in the middle of the eastern sky (as it enters the Earth’s shadow).

The ISS moves at about 18,000 mph, so it travels about 1,500 miles during these quick visions. It’s strange that the station could be mistaken for a plane—yet it is, frequently.

ALL appearances of the ISS start from the west, and end (roughly) in the east.

January 22–23

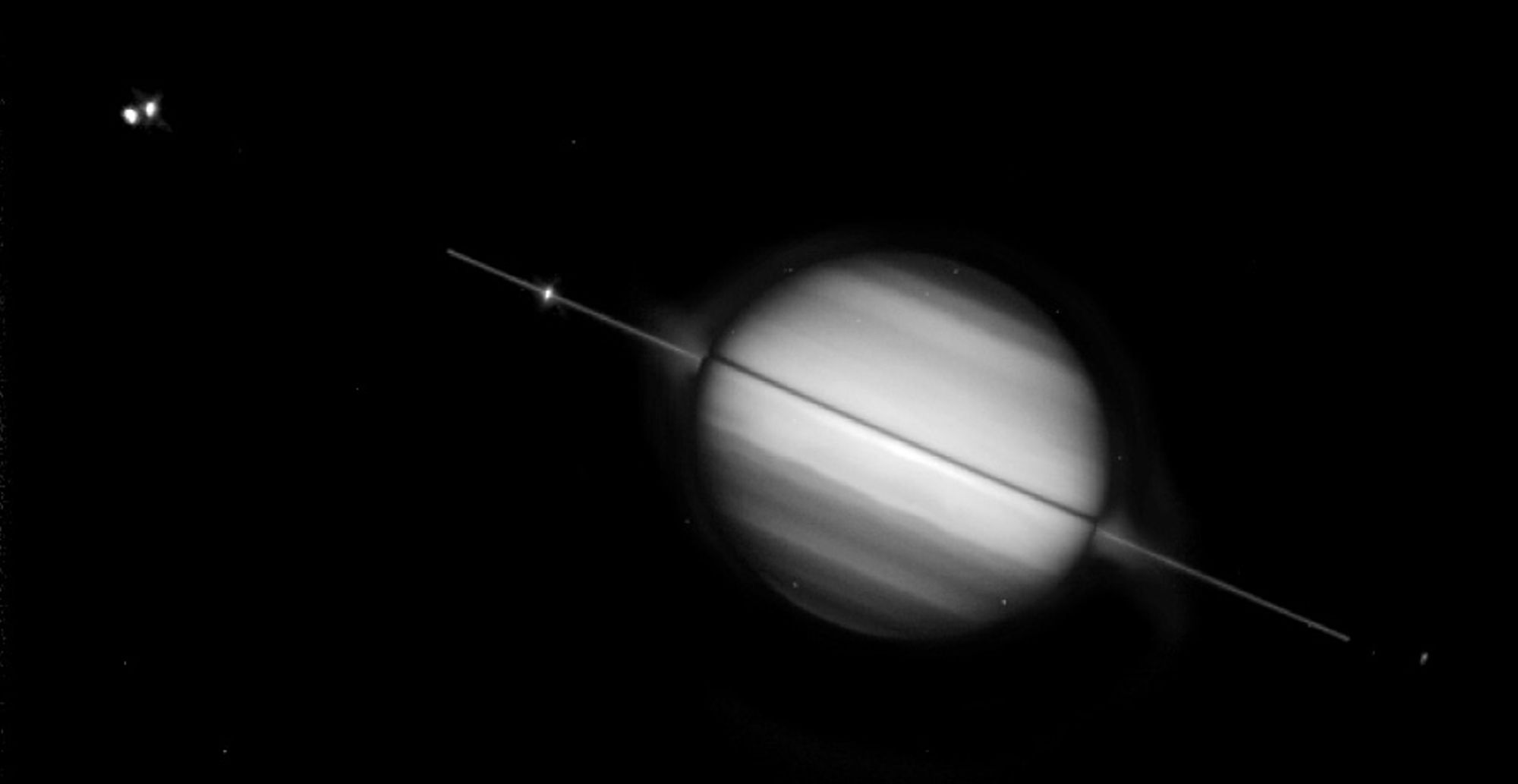

The waxing crescent Moon passes pretty close to Saturn on these nights. Saturn’s rings are pretty close to edge-on this month, so they won’t present the beautiful view we all love. But if you have a decent telescope and a good southwestern horizon, give it a look. As a consolation prize, look for the brilliant Venus, low in the southwest, an hour after sunset. The medium-bright starlike object next to it is Saturn, as a telescopic look will confirm. But you’ll need a really good southwestern horizon.

Saturn's ring system seen tilted edge-on, 1995.

Courtesy of Phil Nicholson (Cornell University) and NASAJanuary 25

First-quarter Moon. Excellent time for telescopic observation—when the mountains and crater walls cast long shadows, as seen from the Earth.

January 27

The Moon is next to the Pleiades tonight. Very nice target for observation through binoculars.

The Pleiades star cluster (M45), photographed from Tõrva, Estonia.

Courtesy of Nielander / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-4.0January 30–31

Things are getting a little crowded up there. On these nights, the nearly-full Moon is practically on top of Jupiter and the Gemini twins.

January 31

Sunrise 7:07 am

Sunset 5:13 pm

February

February 1

Sunrise 7:06 am EST

Sunset 5:14 pm EST

Full Moon at 5:09 pm EST

February 2

Groundhog Day, as we have come to call it. This is the first of the four “cross-quarter days,” roughly the mid-points of the four seasons. The groundhog connection dates back to an old German legend about the predictive power of badgers. In Christian liturgy, it’s also called Candlemas (candles are lit during services).

BTW, since you’re reading a calendar, it’s a fair guess that you’re interested in such things. If so, indulge yourself, visit timeanddate.com, read about this day, and find room for a new habit.

Groundhog Day from Gobbler's Knob in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.

Photo: Anthony QuintanoFebruary 2

The nearly-full Moon is very close tonight to Regulus—the brightest star in Leo and the “backward question mark” of the winter sky.

February 3

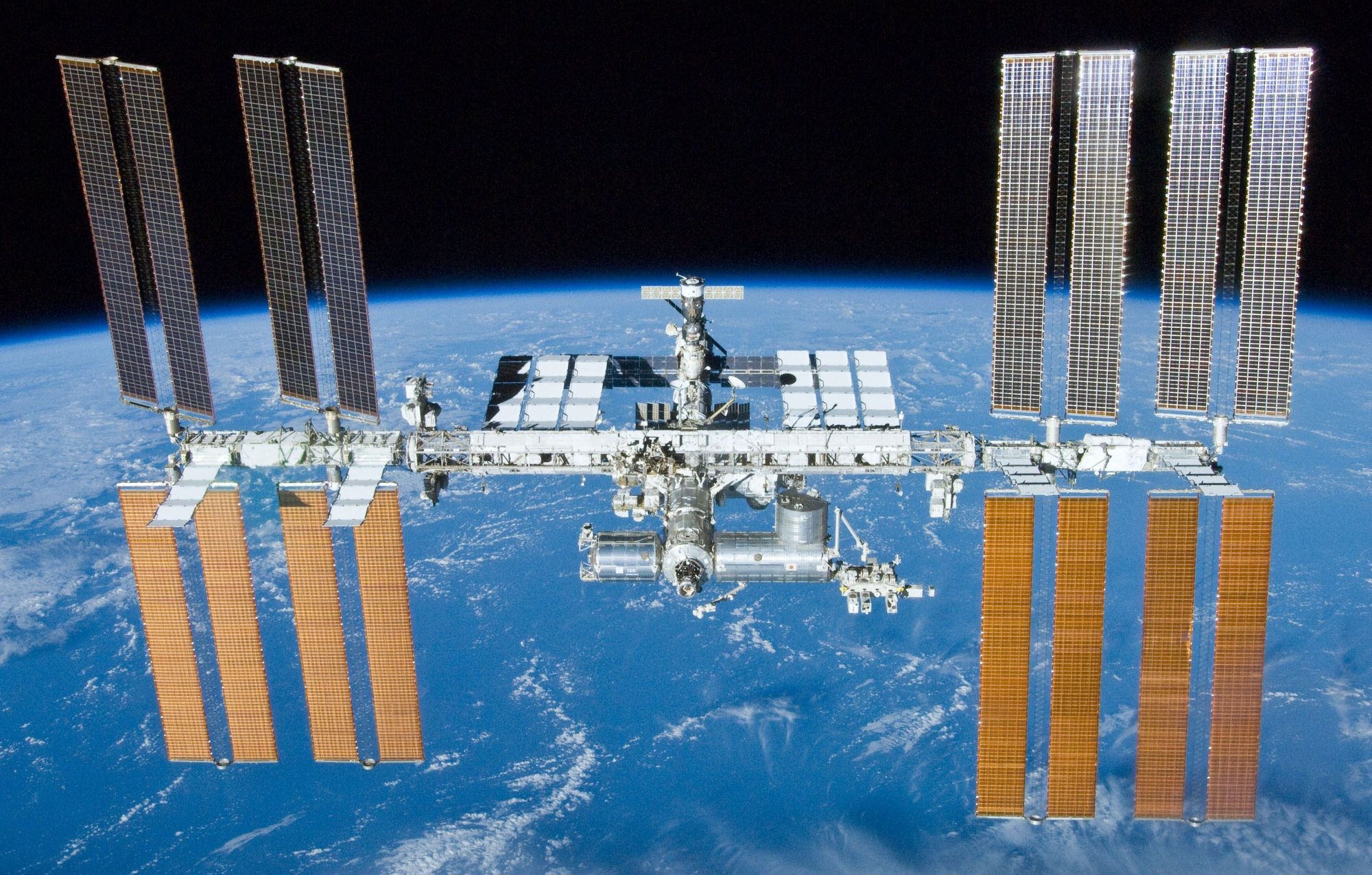

For observers in NYC, the International Space Station (ISS) will make a pass directly over NYC at precisely 6:37 pm EST tonight. These overpasses are dramatic. You’ll first see it low in the NW, at 6:34 pm. It bears repeating that it may resemble a plane—except that it has no flashing lights and appears to be flying directly over NYC (which only hijacked planes do).

At 6:37, directly overhead, it’s as bright as Venus, and at 6:40 it disappears completely in the SE, even though it’s still 30 degrees from the horizon (only UFOs do this). That’s because it’s entering the Earth’s shadow.

The ISS orbits at ~18,000 mph. When you first see it, it’s roughly over Minnesota. Three minutes later, it’s over NYC. You can see why “landing” this giant structure—a football field in size and requiring 42 visits by astronauts to assemble in orbit—will eventually be a gigantic engineering problem.

The International Space Station, photographed by an STS-132 crewman.

Courtesy of NASA / Crew of STS-132February 4

Theoretically, these overpasses happen a lot, but only a few are so conveniently placed and timed for NYC. The only other really good one this month occurs the next night, February 4, starting at 5:46 pm. Same progression and duration. A splendid reward for six minutes of observation!

February 9

Last quarter Moon, rising around midnight.

On this day in 1913, sky-watchers from Saskatchewan to Bermuda saw a great procession of meteors moving rapidly across the sky. There were hundreds, throwing off sparks as they went and maintaining a near-perfect formation. This was probably a tiny comet or asteroid, which happened to strike the Earth’s atmosphere at grazing incidence. It might have dissipated or skipped off the atmosphere, like a flat stone skipping off a pond.

We don’t really know how many such objects are out there. Our detection methods mainly pick up the larger ones, and those are too few to pose a serious concern. 2021 had a real groaner of a movie about one (Don’t Look Up). The 1998 Deep Impact had some silliness too, but the science was spot-on perfect. A 400-foot tsunami roaring over Columbus Circle is just what you’d get with a deep impact in the ocean!

A meteor during the peak of the 2009 Leonid Meteor Shower.

Courtesy of Navicore / Wikimedia CommonsFebruary 15

Sunrise 6:50 am EST

Sunset 5:31 pm EST

Galileo’s birthday in 1564. Very nearly the day of Michelangelo’s death (February 18). Perhaps the greatest scientist and artist of the last millennium.

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Susterman, circa 1640.

Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird CollectionFebruary 17

New Moon 7:01 am EDT.

February 18

First day of Ramadan, probably. The mullahs in Mecca will be carefully scrutinizing the western sky tonight, to glimpse the thin lunar crescent (just following the New Moon). If they see it, Ramadan starts. But they do have modern calendars, so they might bend the rules a bit to allow for cloudy weather.

On this day in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh discovered a faint moving object beyond Neptune, soon named Pluto after the ruler of the underworld. It was considered the outermost planet of the solar system, until it was ruthlessly dethroned in 2006. (Basically, it was deemed too small, too distant, and more closely resembling the “dwarf planets” in the debris at large distances from the Sun.)

This decision was massively unpopular among America’s children, partly because of what they had learned in school, and partly because of Pluto the Dog. Astronomers be warned: Don’t mess with Disney characters.

High-resolution image of Pluto in enhanced color, 2015.

Courtesy of NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research InstituteTonight, the thin crescent Moon gets very close to Mercury in the early-evening sky. It won’t be a barn-burner of a sight, very low in the southwest. I’ve only seen Mercury a few times—and supposedly, even Copernicus never saw it (he relied on Arab observations from earlier centuries). But if you have a clear SW horizon, give it a try! If you see a stationary point of light very near the lunar crescent, that’s Mercury. No telescope needed, of course—only naked-eye observations count. (Maybe binoculars are OK, in a pinch… but get away from any buildings in the southwest!)

February 19

Having visited Mercury yesterday, the lunar crescent pays a visit to Saturn in tonight’s early-evening sky. But no big deal—Saturn is on the Moon’s usual menu for monthly visits.

Lunar crescent, 2025.

Photo: Giuseppe DonatielloBirthday of Copernicus in 1473. Copernicus is often hailed as marking the great transition from medieval to modern ideas about the universe. But historians of science tell a somewhat different story. He seems to have published his master work, On the Revolutions of Heavenly Spheres, from his deathbed in 1543—probably at the urging of his student, Joachim Rheticus. Perhaps despairing that the master would ever publish the full work, Rheticus pre-published his own version in 1540 (Narratio Prima).

Ironically (in view of what happened to later advocates of heliocentrism), Pope Paul III expressed interest in the idea, while Martin Luther called Copernicus “a damn fool.”

February 23

Tonight, the Moon is just north of that famous “Pleiades” star cluster—otherwise known as the Seven Sisters. Great sight in binoculars!

February 26–27

On February 27, 40–60 minutes before sunrise, look low in the southeast for a thin waning crescent Moon. Above it is Mars, and above Mars is the brilliant Venus. On the morning of the 26th, the planets are in pretty much the same place, but the Moon is to the right (as you view it) of the Mars-Venus pair.

You’ll need a good horizon and clear sky (but not crazy-good and crazy-clear) to see these.

Mars seen in true color, taken by the OSIRIS instrument in 2007.

Courtesy of ESA & MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGOVenus, as captured from NASA's Mariner 10 spacecraft, 2020.

Courtesy of NASA / JPL-CaltechFebruary 28

Sunrise 6:31 am EST

Sunset 5:46 pm EST

March

March 1

Sunrise 6:29 am

Sunset 5:47 pm

March 2

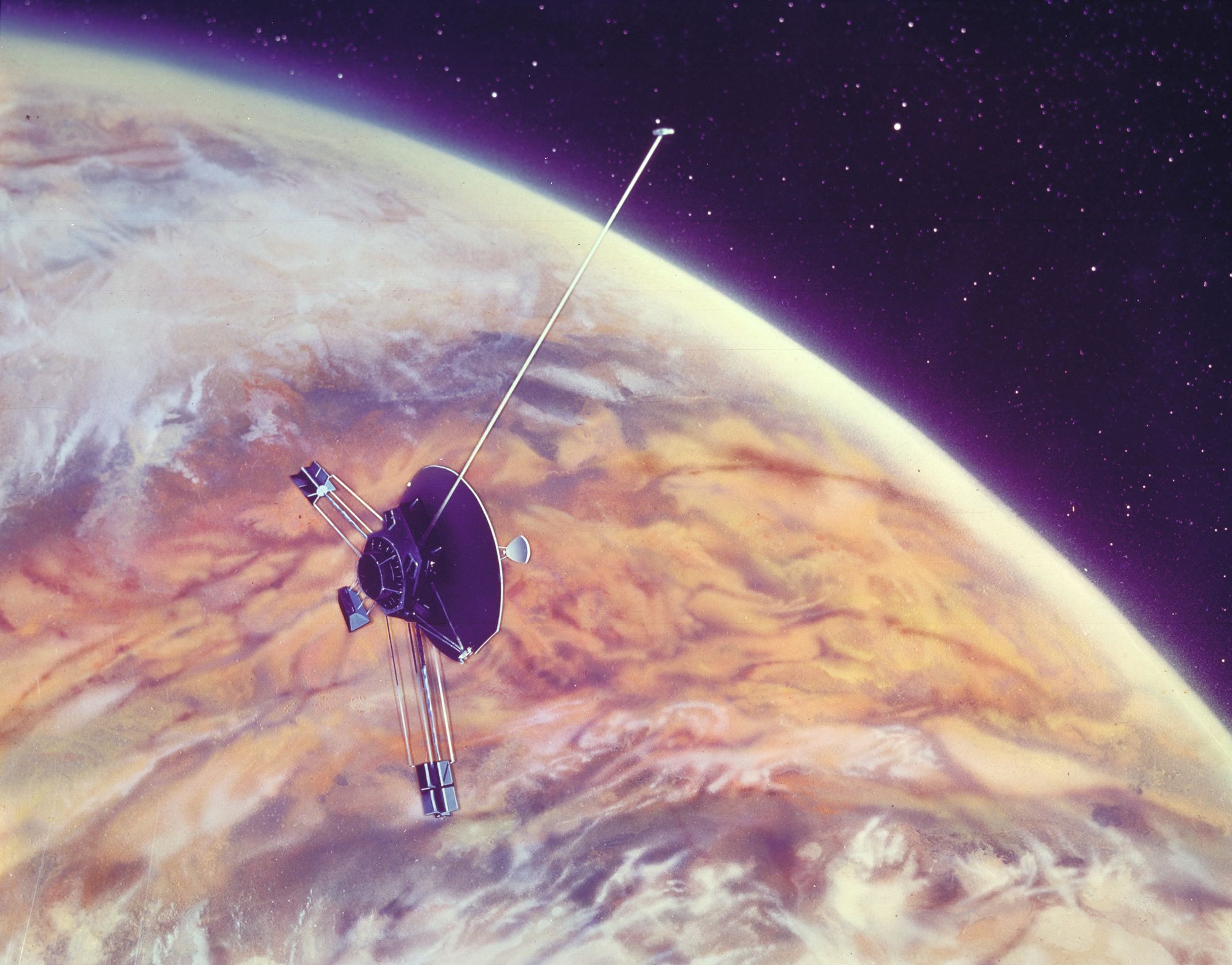

The 50th anniversary of the launch of Pioneer 10, humanity’s most ambitious venture out of our home solar system. The spacecraft was designed to study Jupiter (which it did in 1973), but then went sailing past Neptune—into what you might call “interstellar space.” It’s still there, coasting along at 51,000 mph in the direction of the bright star Aldebaran. It’ll arrive—well, get close, anyway—in a mere two million years. It bears a plaque showing who sent it (a man and a woman), where it came from (third planet from a star), and even a suggestion for what frequency to use in sending a return radio message (1420 MHz, the “song of interstellar hydrogen”).

Seems unlikely the Aldebaranites will figure all that out, but it’s worth a try—assuming, of course, that Jeff Bezos or Richard Branson don’t mount a recovery mission to add Pioneer 10 to their private collections.

An artistic rendering of the Pioneer 10 Spacecraft shown above Jupiter's surface.

Courtesy of NASA Ames Research CenterMarch 3

Full Moon and a total lunar eclipse, because the Moon is now exactly opposite the Sun. Unfortunately for most of us North Americans, it occurs slightly too late at night to be easily visible. It’s mainly a Pacific Ocean affair. On the west coast of North America, you can see most of it if you have a clear view to the west. Mid-eclipse is at 6:34 am EST, so folks in eastern USA will see only the beginning—and even then, they'll need a very clear view down to the western horizon to see the Moon at all.

Total lunar eclipse, 2025.

Photo: BrucewatersMarch 8

The date of the semi-annual rip in the fabric of time, scheduled for 2 am EST on Sunday, March 8 (“spring ahead, fall back”). It’ll go into effect just about everywhere in the U.S., except sunny Hawaii and Arizona, where they presumably don't need any help saving daylight.

March 11

Last quarter Moon, rising around midnight (1 am EDT).

March 13

The anniversary of the discovery of Uranus—the first planet to join the planets of antiquity—by William Herschel in 1781. Uranus was the father of Saturn and the grandfather of Jupiter; William was the brother of Caroline Herschel and the father of John Herschel—famous astronomers all! Although the discovery date is credited as March 13, the object was sighted and catalogued as a star many times previously. On March 13, Herschel realized that it changed positions in the sky, and he therefore classified it as a comet. (Since all planets were known in antiquity, the idea of “discovering” a new planet was just too weird to contemplate.) After tracking it for two more years, he realized that it had no tail, and orbited in a near circle outside the orbit of Saturn. QED: PLANET. Herschel wanted to call it Sidus Georgium (Star of George) to curry favor with the English monarch. But Americans will recall that during 1781–3, George III had to deal with issues more serious than planets.

Uranus, imaged by Voyager 2, 1986.

Courtesy of NASAAlso the exact anniversary of the 1986 flyby (within 600 miles) of Halley's Comet by the European spacecraft Giotto, which snapped some amazing photos. The original Giotto painted a famous fresco, Adoration of the Magi, likely in the year 1320. In it, the Star of Bethlehem is represented as a comet, and we know that Comet Halley visited the inner solar system in 1301. Had old Giotto been around for Halley's 1986 visitation, he would surely have painted the comet in the background of Bill Buckner's famous error to “win” the World Series for the New York Mets.

Granted, it was just the sixth game. But hey—this is art.

Halley's Comet, photographed by Giotto on March 14, 1986.

Courtesy of NASA / ESA / Giotto ProjectMarch 14

PI DAY, the occasion of math celebrations in many schools, after the celebrated transcendental number 3.14159… (now known to at least 62 trillion places), which is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. It’s also the birthday, in 1879, of Albert Einstein. π is prominent in Einstein's famous equation of general relativity (Gμν = 8πGTμν), but we're pretty sure that he didn't know π to any more places than the average 8th grader (3.14).

Newton, on the other hand, once said that he was “ashamed” that he had calculated it to 16 places. Now there’s a mighty challenge to today’s 8th graders!

March 15

Sunrise 7:07 am EDT

Sunset 7:02 pm EDT

The Ides of March, when Julius Caesar was assassinated in the Roman Senate.

The Death of Julius Caesar by Vincenzo Camuccini, circa 1804.

Courtesy of Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di RomaMarch 18

New Moon 9:23 pm EST

March 20

Vernal equinox at 10:46 am EST. No matter where you live on Earth, the Sun today rises exactly in the east, sets exactly in the west, and is in your sky exactly 12 hours. Hence equi-nox (equal night). Except for the ~0.0001% of humanity “living” within a few degrees of the North or South Poles. For them, the Sun just grazes the eastern or western horizon as it rises or sets—executing a huge 360-degree daily spiral, always within a few degrees of the horizon.

Sunset in eastern Nepal, 2019.

Photo: Babin DulalI had the opportunity to observe this when I was 13 years old. I was on an over-the-pole 26-hour flight in a propeller plane on the day of the equinox! The Sun rose and set three times—never straying more than a few degrees above or below the horizon. (Of course, at the time I had no idea why.)

March 23

In the year 2178, exactly one Plutonian year will have passed since Pluto's discovery. Seems likely that by then, the number of Disney-loving children, divided by the number of known TNOs (Trans-Neptunian Objects), will have decreased sufficiently to put the planet controversy to a merciful end.

March 25

Pretty close to the vernal equinox, and the exact date for the beginning of the year in Merry Olde Englande. Hence some of the names for months: SEPTember was the seventh month, OCTober the eighth, NOVember the ninth. DECember was the tenth. January and February were just add-ons to be endured—what could you do when it was so cold, and the Earth so barren?

In 1752, Parliament decided to eat humble pie and adopt the calendar reform instituted by Pope Gregory and adopted by most of the Catholic world in 1582: Henceforth, the year number would change over on January 1. As for March 25, it was pretty close to the equinox (nice)—but more importantly, it was precisely the Feast of the Annunciation, when the archangel Gabriel announced you-know-what to a certain surprised young woman. And let's see... if you count exactly nine months after that, you come to another interesting date. A few astronomers were probably paid a few quid to make it all fit together.

Annunciation by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1472.

Courtesy of the Uffizi GalleryFirst quarter Moon, high in the sky near sunset and setting near midnight. Great time for lunar viewing through a telescope.

March 31

Sunrise 6:41 am

Sunset 7:19 pm ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast