Big Apple Sky Calendar: October, November, December 2025

In the 1990s, astronomy professor Joe Patterson wrote and illustrated a seasonal newsletter, in the style of an old-fashioned paper zine, of astronomical highlights visible from New York City. His affable style mixed wit and history with astronomy for a completely charming, largely undiscovered cult classic: Big Apple Astronomy. For Broadcast, Joe shares current issues of Big Apple Sky Calendar, the guide to sky viewing that used to conclude his seasonal newsletter. Steal a few moments of reprieve from the city’s mayhem to take in these sights. As Oscar Wilde said, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

—Janna Levin, editor-in-chief

October

October 1

Sunrise 6:52 am EDT

Sunset 6:38 pm EDT

Notice that daylight is now less than 12 hours—we've passed the equinox.

October 4

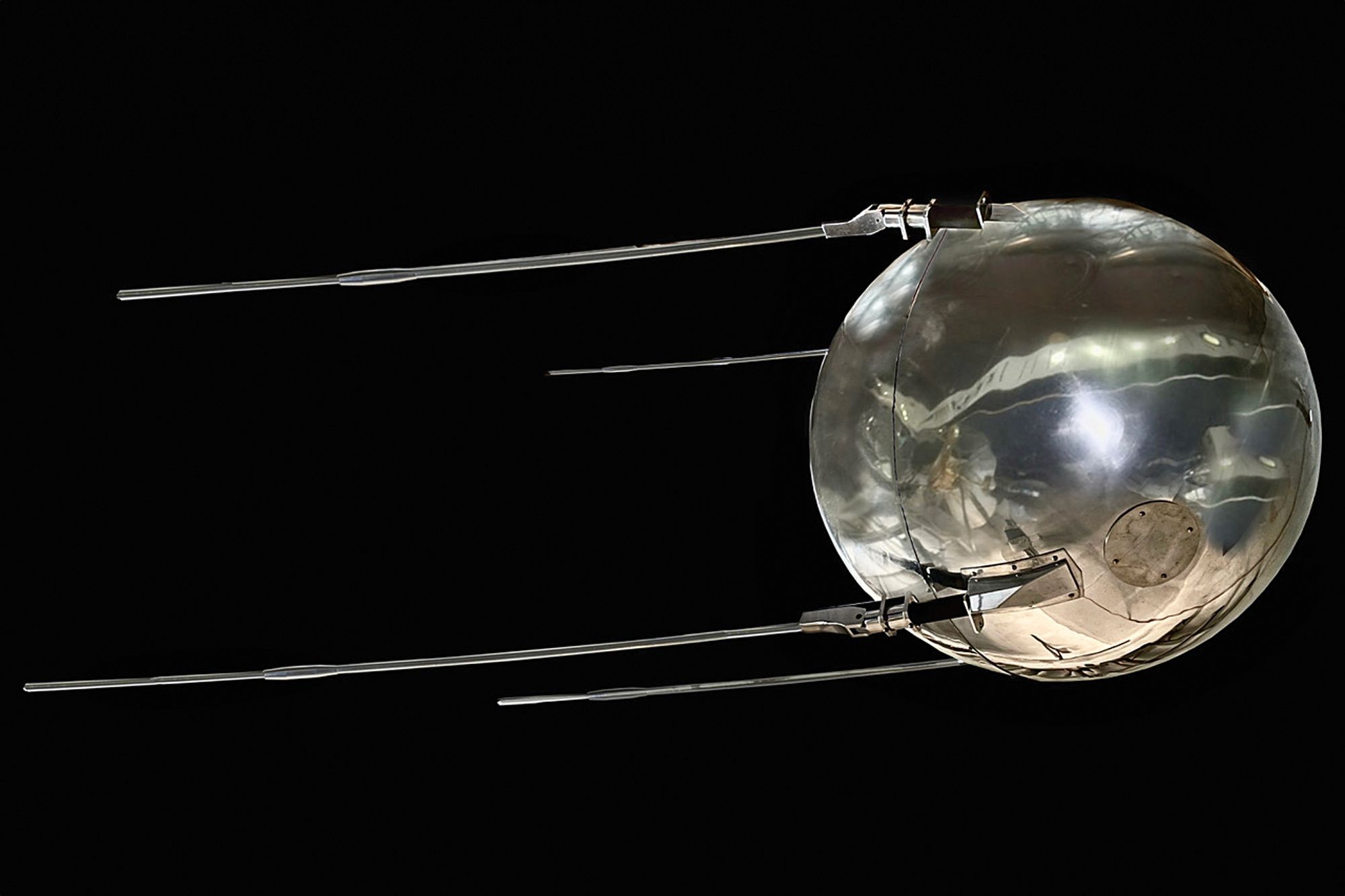

On this day in 1957, the Soviet Union startled the world by announcing that it had launched Sputnik, the first artificial Earth satellite. It was just a little metal sphere, but it carried a radio transmitter which allowed the world to verify its existence and track its orbit. Alongside the U.S. lunar landing in 1969, this moment is remembered as humanity's first venture into space.

Sputnik 1 was quickly followed by the much larger Sputnik 2, which carried a dog, Laika, who actually managed to survive for a few orbits. Laika became an international folk hero; her story (or stories—there are many versions) is well told in the National Air and Space Museum and in Smithsonian magazine. She belongs with Balto and Hachiko in the pantheon of dog heroes.

Full Scale Shell of Sputnik.

Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsOctober 5

Tonight’s evening sky features the third quarter Moon passing just north of Saturn.

On this day in 1882, Robert Goddard was born. At the age of 17, on a day which he always called his “Anniversary Day,” he climbed a cherry tree and dreamed of building a machine that would travel to Mars. As we all know, the successors to his rockets did travel to Mars—in particular, the Mariner spacecraft of the 1970s. But Goddard had to battle enormous skepticism about his plans. His first test rocket rose 114 feet and landed in a nearby cornfield; a newspaper greeted his success with the headline: “Moon Rocket Misses Target by 239,785 miles.”

The New York Times ran a famous article criticizing him for ignoring “the facts ladled out in every high school”—namely, the incorrect claim that you need something to push against for propulsion in the vacuum of space. In the aftermath of the July 1969 Apollo landing, the Times republished their critique, followed by the simple correction: “The Times regrets the error.” (Notably without explaining why their earlier analysis of the physics was incorrect.)

However, Goddard had some powerful and early allies, who knew more physics than The New York Times: Charles Lindbergh, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Guggenheim family. And late in World War II, after the Germans demonstrated the enormous potential of rockets (the V-1 and V-2), there was a mad scramble by Russian and U.S. troops to kidnap German scientists for their own military programs. The U.S. got the most and sent them to New Mexico to work with Goddard.

October 6

Full Moon 10:48 pm EDT

This is called the Harvest Moon, as it's the full Moon nearest the autumn equinox. Because the Moon is opposite the Sun, it rises when the Sun sets and the bright moonlight allows you to extend your harvesting time by a few hours.

The Harvest Moon is my first remembered experience in astronomy. One day around evening twilight, I saw a big old orange ball hanging low in the East. I asked my mother what it was, and she replied, “It’s the Harvest Moon.” Somehow, this answer seemed satisfactory at the time. Maybe I thought the orange color meant it was ready for harvesting.

October 6–14

These were the days that never existed for most of Europe in 1582. The inaccuracies of the Julian calendar had caused an error of nine days to accumulate between the calendar and the dates of seasonal phenomena (solstices, equinoxes). This was worrisome to the Catholic Church because it meant that the timing of Easter was slipping away from its historic connection to Passover and springtime. Thus the Gregorian calendar was born, improving the leap year convention and restoring calendar agreement by legislating nine days out of existence. It caused a lot of social unrest too—landlords charging rent for the missing days, etc.

The Gregorian calendar isn’t perfect either. Its error accumulates to about one day per millennium—good enough for practically everyone, except some enterprising souls determined, in odd ways, to make the world a better place. Recent proposals have impressive names like Equitable Calendar, International Fixed Calendar, Edwards Perpetual Calendar, etc. Another possibility is that we’ll go to a completely metric system of time, with millidays, centidays, etc. This was attributed in the 1976 Church Times to “an anonymous joker in Norfolk,” though one kiloday it may not be a joke.

October 7

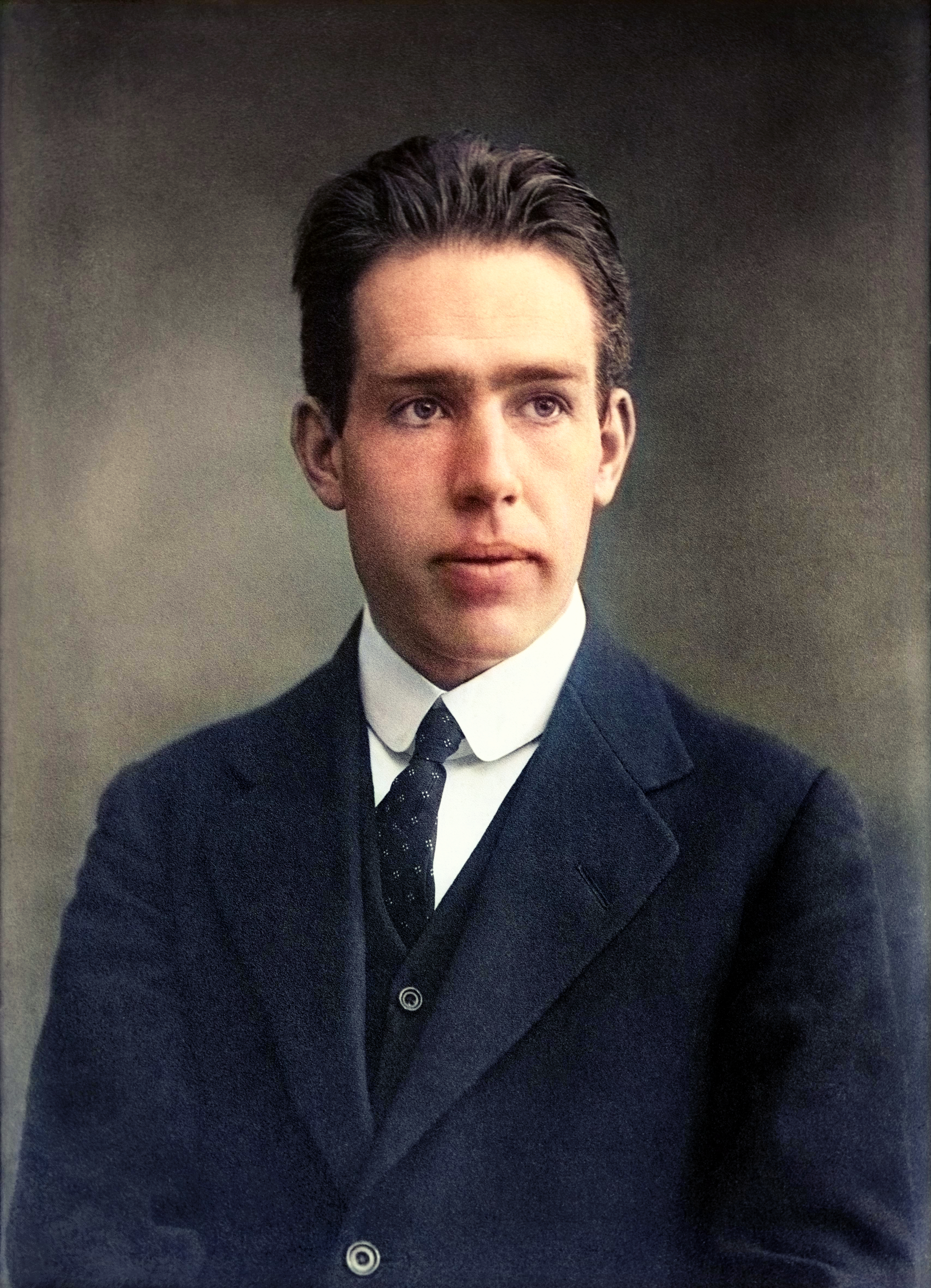

Birthday of Niels Bohr in 1885. Bohr became famous for the “Bohr model” of the atom, which depicted each atom as a “miniature solar system,” with a massive central nucleus of positive charge (consisting of protons), surrounded by negatively charged electrons in very distant orbits. Although it was mostly superseded by the invention of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, the Bohr model remains the way that practically all astronomers think about atoms. For most of the century, Bohr's institute in Copenhagen became a mandatory stop for nearly all European physicists.

October 9

On this evening in 1992, a 28-pound meteorite crashed into a parked car in Peekskill, New York—the only known such event in history. The last few seconds of the meteor’s path were well photographed because a high school football game was going on next door. The car was a 1980 Chevy Malibu, recently purchased for $300 by a 17-year-old girl. It later sold at auction for $50,000.

October 11

Autumn Starfest from 7–10 pm.

Join the AAA (Amateur Astronomers Association) for a night of observing (99th Street and Central Park East). Weather (clear sky) permitting. See aaa.org (not the car organization) for details concerning this and all AAA events.

October 12

Solar observing at Pioneer Works from 1–4 pm. 159 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn—weather permitting.

October 13

The last quarter Moon rises around midnight. It’s practically on top of the Gemini twins (Castor and Pollux) tonight.

October 15

Sunrise 7:07 am EDT

Sunset 6:15 pm EDT

October 15

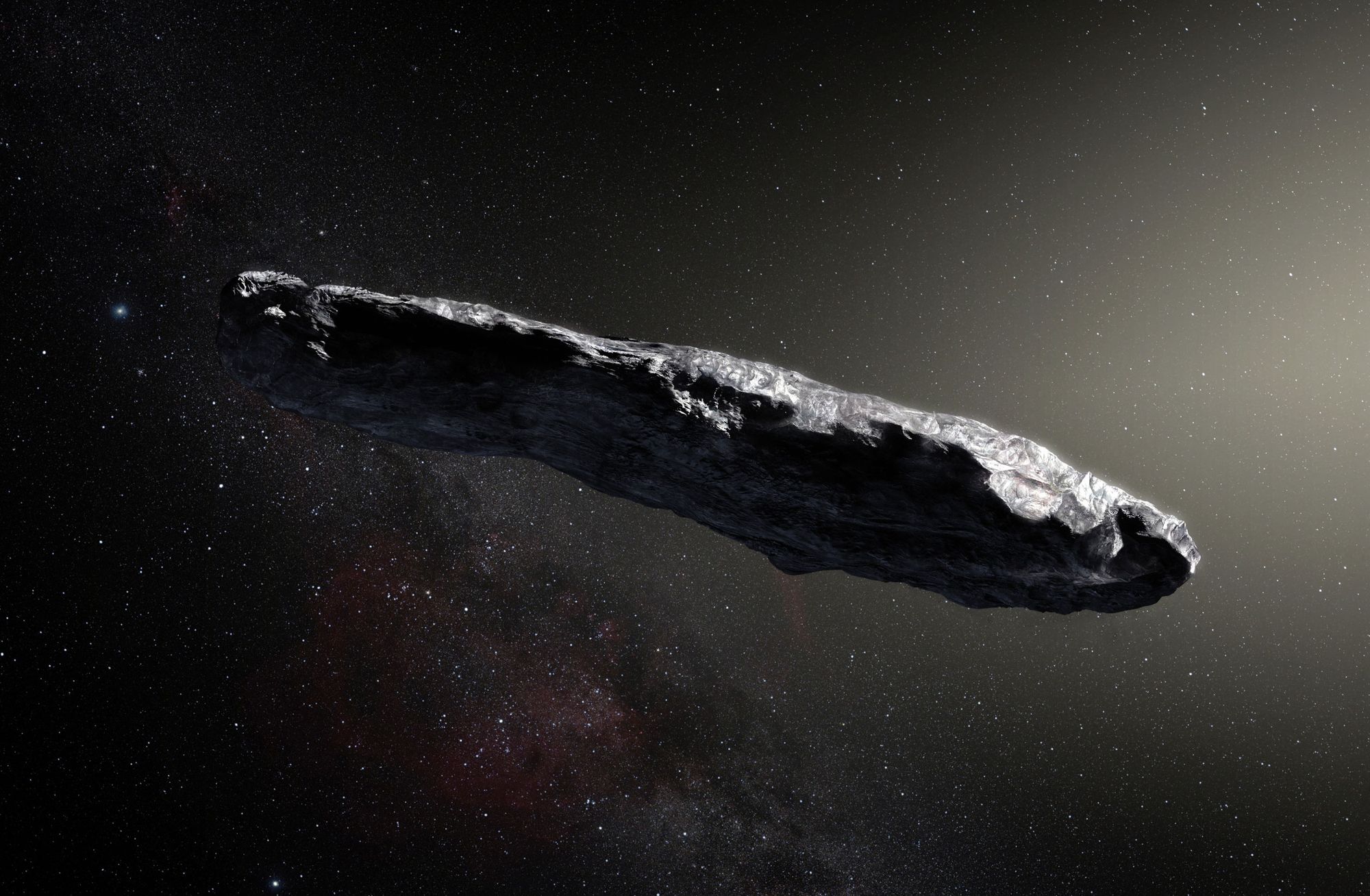

On this date in 2019, observers in Hawaii reported the discovery of what might be the strangest astronomical object in history. It was possibly cigar-shaped, moving through the solar system faster than anything else ever found and seemingly violating Newton's Laws. In a famous or maybe infamous paper, a Harvard astronomy professor suggested it might be an alien spacecraft. It received the name "ʻOumuamua"—Hawaiian for "scout from afar." More recently, two similar objects were found, and they're now called "interstellar comets." But you've gotta love the swashbuckling name of the first!

An artist’s rendering of the first interstellar asteroid, ESO/M. Kornmesser.

Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsOctober 21

New Moon 8:25 am EDT

October 21–22

Early this morning (on the 22nd), the Earth “collides” with the orbit of Halley's Comet. The comet itself is long gone (totally invisible, somewhere in the rough vicinity of Neptune), but its dust debris, shed by solar heating during thousands of previous visits to the inner solar system, continues to orbit the Sun. There's a continuous trail of dust along all the places the comet has recently been. Twice a year, in October and May, the Earth’s orbit carries us through that trail, and a meteor shower occurs as the dust particles burn up in our atmosphere. Away from city lights tonight, a naked-eye observer might see around 20 meteors per hour.

They're called “Orionid” meteors because they'll appear in the rough (VERY rough) vicinity of Orion. More correctly, they'll appear to emanate from Orion—but appear all over the sky. Despite a mediocre ranking among the annual showers, the Orionids are my favorite for observing. Why? Because Orion, grandest of the constellations, hasn't been properly seen since March, and the October mornings still permit viewing without frozen fingers. It's also a chance to welcome back all those winter constellations. This year, there’s no moonlight to hamper the view.

October 23

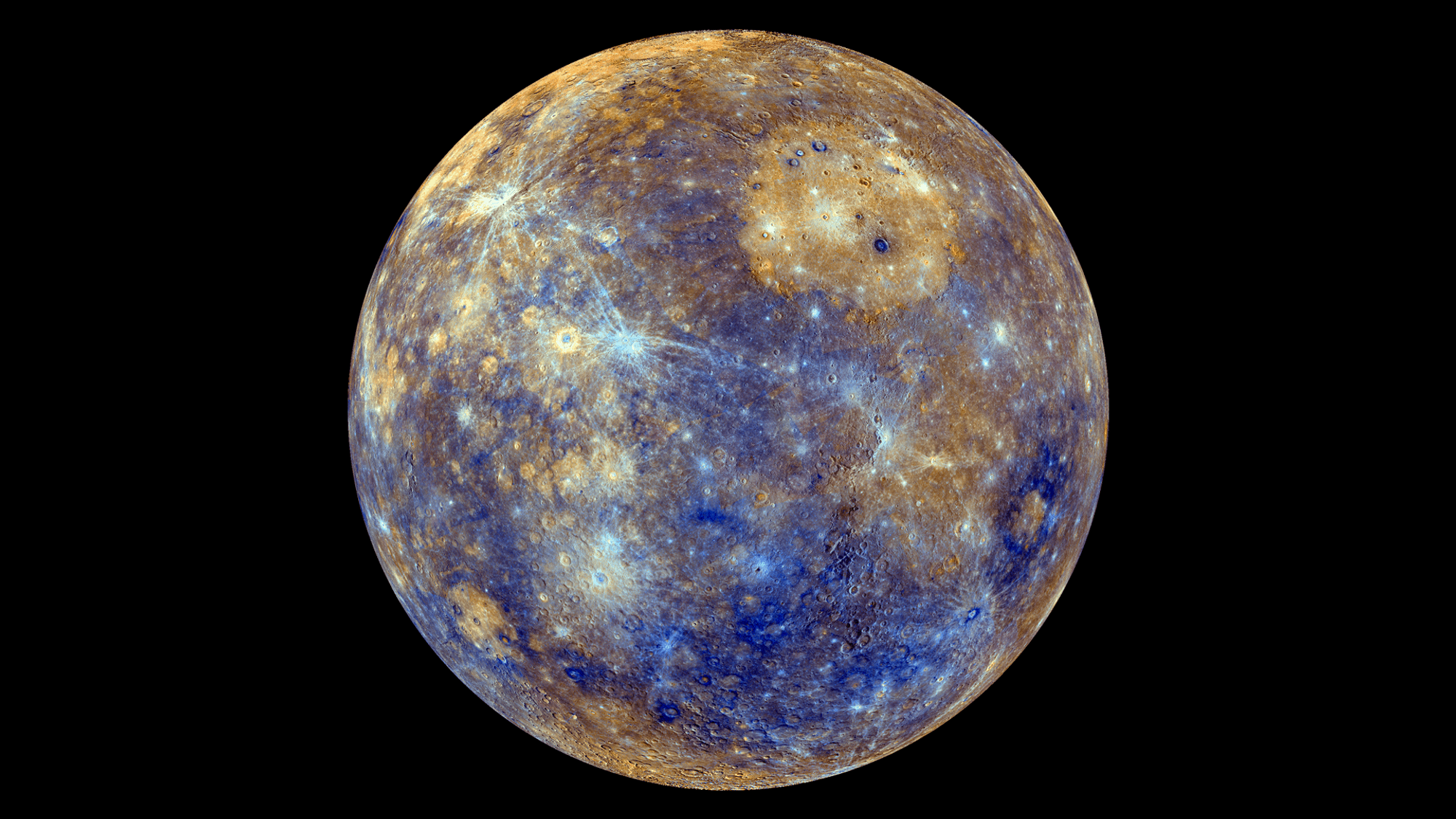

In tonight’s evening sky, if you have a clear western horizon, look for a bright starlike object just west of the (very thin) crescent Moon. It’s Mercury! Very few people have ever seen it, because it’s always so close to the Sun. Even Copernicus never did.

October 29

First quarter Moon, setting around 1 am. Any night within a few days is a good time for telescopic lunar viewing because the angle of the Sun (near 90 degrees) will cast long shadows on the lunar surface.

October 31

Sunrise 7:25 am EDT

Sunset 5:53 pm EDT

November

November 1

Sunrise 7:26 am EDT

Sunset 5:52 pm EDT

November 2

End of daylight saving time. At 2 am EDT, wake up and set your clocks back to 1 am—except in Hawaii and Arizona, which have plenty of daylight and have opted not to participate. This gets you back in reasonable harmony with the Earth-Sun clockwork.

November 5

Full Moon. The Moon is at perigee, so watch out for very high tides today and tonight.

November 7

Birthday of Marie Curie (née Sklodowska) in Warsaw in 1867. The only person ever to win Nobel Prizes in different fields: Physics in 1903 and Chemistry in 1911.

November 8

Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in his lab in Germany in 1895. On this day of discovery, he found that these rays were a new form of light of much higher energy—and that they were extremely penetrating, revealing the bones in animal tissue. Within a few months, X-rays were used to find bullets in wounded soldiers. In the 1960s, it was also found that many stars were copious natural emitters of X-rays—including the famous Cygnus X-1, the first black hole ever identified.

November 9

The Moon is just north of Jupiter tonight, and just south of the Gemini twins (Castor and Pollux).

November 12

Last quarter Moon, rising around midnight. On these two nights, the Moon passes near Mars. The Red Planet is rapidly brightening as it approaches its dramatic December 8 opposition (closest approach to Earth). Look at it up there, slightly above the constellation Orion.

Stargazing tonight for the public, 8–11 pm at Lincoln Center Plaza, weather permitting.

November 14

Birthday of Frederick Banting in 1886. I just had to mention it. No astronomical significance whatsoever. But there are very few movies about scientific discovery. Two great ones, in my opinion, are Galileo, a CBC production of Bertolt Brecht’s play, and Glory Enough for All (about Banting’s discovery of insulin). Another is Inherit the Wind (about the Scopes “Monkey” Trial). Lots of opportunities for new flicks. A really good cartoon movie, by Frank Capra, is The Strange Case of the Cosmic Rays (part of the old Bell Telephone series of shorts on science).

November 15

Sunrise 6:42 am EST

Sunset 4:38 pm EST

November 16–17

Last quarter Moon. Stargazing at Pioneer Works, 7–10 pm, weather permitting. It's also the anniversary of the 1974 “Arecibo Message,” the first attempt to send a message to extraterrestrial listeners about who we earthlings are. It was aimed at the globular cluster M13, which has about 100,000 stars. Who knows, maybe someone will receive it. It’s brief and primitive, but ingenious. But don’t expect a reply: M13 is 100,000 light-years distant.

Tonight is the peak night of the Leonid meteor shower, occurring when the Earth collides with dust debris strewn around the orbit of Comet Tempel-Tuttle. The comet itself is nothing special and is now out there beyond Jupiter. It's an ordinary comet, but at least once spewed a huge hunk of dirt and ice, which continues to orbit the Sun with the parent comet’s 33-year period. Astronomers keep an eye out each November 16–17, when we collide with "the orbit.” That apparently happened on November 13, 1833, when Boston observers reported meteors falling “like snowflakes in an average snowstorm.” Other great displays were seen in 1868 and 1966. Nothing special is expected this year, but comets and their debris are famously fickle. Roz Chast once likened comets to NYC landlords: they live very far away, with a heart made of ice and stone.

November 20

New Moon 1:47 am EST

November 21

The Sun enters the astrological sign Sagittarius.

November 23

The Sun enters the constellation Scorpius. Didn't stay long in Sagittarius, did it? And shouldn't it be traversing these constellations in the opposite order? Truth be told, astronomers—mostly the Brits—paid only rough attention to astrological boundaries when they divided up the sky in the nineteenth century. They had a difficult task: make the star pattern roughly resemble a scorpion, maintain the rough boundaries of old star maps, and assign each zodiacal constellation one-twelfth of the Sun’s path. On top of all this, they were well aware that the Earth's 26,000-year axial precession would make their assignments gradually obsolete. So, in the 2,000 years since traditional zodiacal boundaries were set, things have moved almost an entire constellation.

But it could have been worse: those Brits could have put Queen Victoria in the sky!

November 27

Thanksgiving. No astronomical significance whatsoever. But if you adopt the (highly recommended) practice of giving thanks at dinner, here's one for you: give thanks that the Moon and the Sun have the same angular diameter (0.5 degrees). And if you're pretty savvy, tell your dinner companions why it's worth celebrating. (They'll think it's weird, but tell them anyway.) Plus, if you're shrewd about such matters, tell them why it will not always be so. We live at a special time in history.

Note for those gutsy enough to take up my suggestion: it’s because the Moon is slowly spiraling away from the Earth, as it steals angular momentum from our rapidly spinning planet. In another billion years—no more total solar eclipses!

November 28–29

First quarter Moon. The medium-bright object near the Moon on these evenings, shining with a steady yellowish light, is Saturn. Usually great for telescopic viewing, of course—but not this year, because the very thin rings are close to edge-on.

November 30

Sunrise 6:59 am EST

Sunset 4:29 pm EST

Each year on November 30, the Sun travels through Ophiuchus (the Serpent Bearer), a sign missing from the standard zodiac list.

On this day in 1934, an Alabama woman (Ann Hodges) was napping on her couch when a 10-pound space rock ripped through her ceiling and struck her on the hip—the only known case of a human hit by a meteorite. She hoped to make some $$ by selling it, but so did the homeowner, and it eventually wound up in the Alabama Museum of Science.

December

December 1

Sunrise 7:01 am EST

Sunset 4:28 pm EST

December 2

On this date in 1942, the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved by the Manhattan Project scientists in an underground squash court at the University of Chicago. Working under the direction of Enrico Fermi, the team found that by bombarding uranium with neutrons, the uranium would fission into lighter elements, which would in turn trigger further fission in other uranium nuclei—each time with energy release (because mass is lost, and E = mc²). This was the basis of the atomic bomb. They had anticipated this outcome but needed to find a way to control the reaction—otherwise, building a bomb would risk blowing themselves up (along with much of Chicago). After the tense but successful experiment, the team cabled to the super-secret agency, “The Italian navigator has discovered the New World.” The cryptic reply came: “How were the natives?” eliciting the answer, “Very friendly.”

December 3

The nearly Full Moon is just north of the famous star cluster “The Pleiades” tonight.

December 4

Full Moon 6:14 pm EST

Death of Omar Khayyam in 1148. Perhaps the last of the great Persian astronomers—and my favorite.

Up from Earth's center through the Seventh Gate,

I rose, and on the throne of Saturn sate.

And many knots unravell'd by the road

But not the knot of Human Death and Fate.

December 8

Earliest sunset for NYC (4:27 pm). This might be surprising—why isn't it on the December solstice, which is always the shortest day (9 hours and 15 minutes)? It's because the exact time of “solar noon” (when the Sun is directly south) wanders by as much as 15 minutes during the year, due to the Sun's variable motion (owing to the slight eccentricity in the Earth's orbit). Also, it's only “earliest” by a gnat's eyelash. The NYC sunset varies by no more than 10 minutes for every December day.

December 11

Last quarter Moon, rising around midnight.

December 13–14

The Geminid meteors. Roughly after midnight on these nights, the Earth passes through the orbit of the asteroid Phaethon (just the orbit, not the asteroid itself), and a large supply of tiny particles burn up in our atmosphere. These are called Geminid meteors, because they appear to come roughly from the vicinity of the constellation Gemini. It’s the most prolific of the annual showers (approximately 100 meteors per hour), but the timing (after midnight, when Gemini is reasonably high in the sky) means that you should expect cold weather. A sleeping bag and a companion to keep your spirits high (“There’s one!”) are highly recommended. And perhaps a reclining chair; human necks are not naturally designed for this activity.

And for gaps between meteors, savor the majesty of Orion, a tad south of Gemini:

Thou splendid soulless warrior,

Ghost of the shimmering summer dawn,

King of the winter nights!

December 16

Birthday in 1917 of Sir Arthur C. Clarke, the great prophet of the Space Age (along with Willy Ley). His great space trilogy includes his non-fiction book The Exploration of Space, his novel Childhood’s End, and his movie (with Stanley Kubrick), 2001: A Space Odyssey. I even have a (borderline!) personal connection. My college girlfriend (the first American born in Pakistan) told me of a British man who taught her to swim and dive on a beach in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Her description matched Clarke in nationality and age. He lived in Colombo, was a pal of her ambassador-father, and wrote books on outer space and diving. She thought it was him, and it had to be.

For a much shorter read, I recommend The Nine Billion Names of God.

December 19

New Moon 8:43 pm EST

December 21

December (winter for us borealites) solstice at 10:03 am EST.

December 25

Christmas. The exact timing of Jesus's birth is highly uncertain. Neither the day, month, nor year is known. Early Christians may have favored a day near the winter solstice because that signifies the seasonal rebirth of the Sun's gifts (warmth and light). And some Christians celebrate January 6; that might be the origin of the “12 days of Christmas.” Some astronomers have tried to find an astronomical event (planetary conjunction, nova, comet, etc.) around that time, linked to the story of the Magi “who saw a star in the east.” These are my favorite themes in planetarium shows. But none of those events occur in the year zero (most are in the range 2–6 CE). It’s also hard to understand how an astronomical sighting can indicate a particular place on Earth, as implied in the Gospel of Matthew, the only source for the story. Everything in the sky moves!

Isaac Newton was also born on this day in 1642. Isaac's father had died a few months earlier, and Isaac's mother soon remarried, leaving the young Isaac to the care of his grandparents. René Descartes, the other intellectual giant of the seventeenth century, had a similar childhood.

December 26

Saturn and the Moon are very close together in tonight’s evening sky.

December 27

First quarter Moon. Also, Johannes Kepler was born on this day in 1571. Kepler's derivation of the precise orbits of planets (ellipses) was the first to establish that the planets moved in a precise geometric pattern. Arthur Koestler wrote a great book about Kepler called The Watershed. It was part of an equally great book about the Scientific Revolution, The Sleepwalkers. Read one of them. Very gifted writers seldom take on scientific subjects, but when they do, it’s magical!

December 28

Arthur Eddington was born on this day in England in 1882. In the early days of the twentieth century, knowledge of physics among astronomers—especially American astronomers—was rare. But Eddington was a gifted mathematician and physicist, and thoroughly acquainted with all the new advances from Einstein, Bohr, Rutherford, and Planck. (American physics was a tad moribund in those days.) He understood their implications for how energy is produced in stellar cores—and wrote about it beautifully in popular books, as well as technical journals. In college, I was enchanted by his books, especially The Nature of the Physical World.

December 31

Sunrise 7:19 am EST

Sunset 4:38 pm EST. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast