Atomic Fireballs: Artists,

Activists and the Bomb at 75 (Part II)

This essay is part of the bomb at 75—a virtual experience dedicated to the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seventy-five years ago, as well as the existential dangers that we still face today. It is paired with a limited podcast series wherein author Eric Schlosser and artist Smriti Keshari talk with six preeminent experts in the nuclear field about their personal histories, current work, the shocking and fascinating scenes that they have witnessed, and their hope and messages for the future. Read Part I here.

Fearing that the Red Army could quickly overrun Western Europe, the United States used the threat of a nuclear attack on Russian cities to deter the Soviet Union and defend its NATO allies. American atomic bombs seemed to be all that stood in the way of a Communist invasion—and American propaganda tried to normalize nuclear weapons, reassuring the public that a nuclear war wouldn’t be the end of the world. The Soviet development of atomic bombs made the task seem urgent. “Survival Under Atomic Attack” (1950), a pamphlet widely distributed in the United States by the Federal Civil Defense Administration, provided useful and encouraging household tips:

YOUR CHANCES OF SURVIVING AN ATOMIC ATTACK ARE BETTER THAN YOU MAY HAVE THOUGHT… EVEN A LITTLE MATERIAL GIVES PROTECTION FROM FLASH BURNS, SO BE SURE TO DRESS PROPERLY… KEEP A FLASHLIGHT HANDY… AVOID GETTING WET AFTER UNDERWATER BURSTS… BE CAREFUL NOT TO TRACK RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS INTO THE HOUSE

The pamphlet was later made into a film, which made this assertion: “If the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had known what we know about civil defense, thousands of lives would’ve been saved.” The claim not only implied that the victims of the atomic bombings were in some way responsible for their own deaths, but it also promoted the idea that shutting your curtains could save your family from a nuclear blast.

The historians Guy Oakes and Andrew Grossman have argued that the underlying goal of Cold War civil defense exercises and propaganda was “emotional management.” None of the official advice needed to work, it just had to maintain popular support for America’s nuclear weapons. Hoping to boost morale as the Soviet hydrogen-bomb program gained momentum, President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration staged Operation Alert in 1955, the largest civil defense drill in American history. During its mock attack on the United States, sixty-one cities were hit by Soviet nuclear weapons. Families across the country rehearsed their escape routes and shelter plans. President Eisenhower and members of his cabinet were taken to secret locations and kept there for three days. In New York City, everybody was cleared from the streets and kept inside for ten minutes, preparing for the arrival of a Soviet hydrogen bomb—whose ground zero, for some reason, was to be the corner of North 7th Street and Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Federal authorities publicly called Operation Alert a great success. But President Eisenhower knew the whole thing was a charade, subsequently recording in his diary what would really happen after such an attack: “Something on the order of 65 percent of the [American] population would require some sort of medical care, and in most instances, no opportunity whatsoever to get it...” He later told officials at a national security meeting that “There just aren’t enough bulldozers to scrape the bodies off the streets.”

Nevertheless, American mass culture followed the official line and supported government efforts at emotional management. “Atomic Power,” a country song recorded by several artists, became a hit in 1946. Written by Fred Kirby the day after Hiroshima’s destruction, its lyrics suggested that “the mighty hand of God” had given the atomic bomb to America and that “Hiroshima and Nagasaki paid a big price for their sins.” The producers of the first Hollywood film about the making of the atomic bomb, The Beginning or the End (1947), set out to provide a morally ambiguous look at America’s nuclear arsenal. As a recent book reveals, the film wound up with a title selected by President Truman, a script rewritten at the direction of the general who headed the Manhattan Project, and a patriotic message justifying the use of the atomic bomb. That same year, CBS broadcast an hour-long radio show promoting the official view of atomic energy, with the title “The Sunny Side of the Atom.”

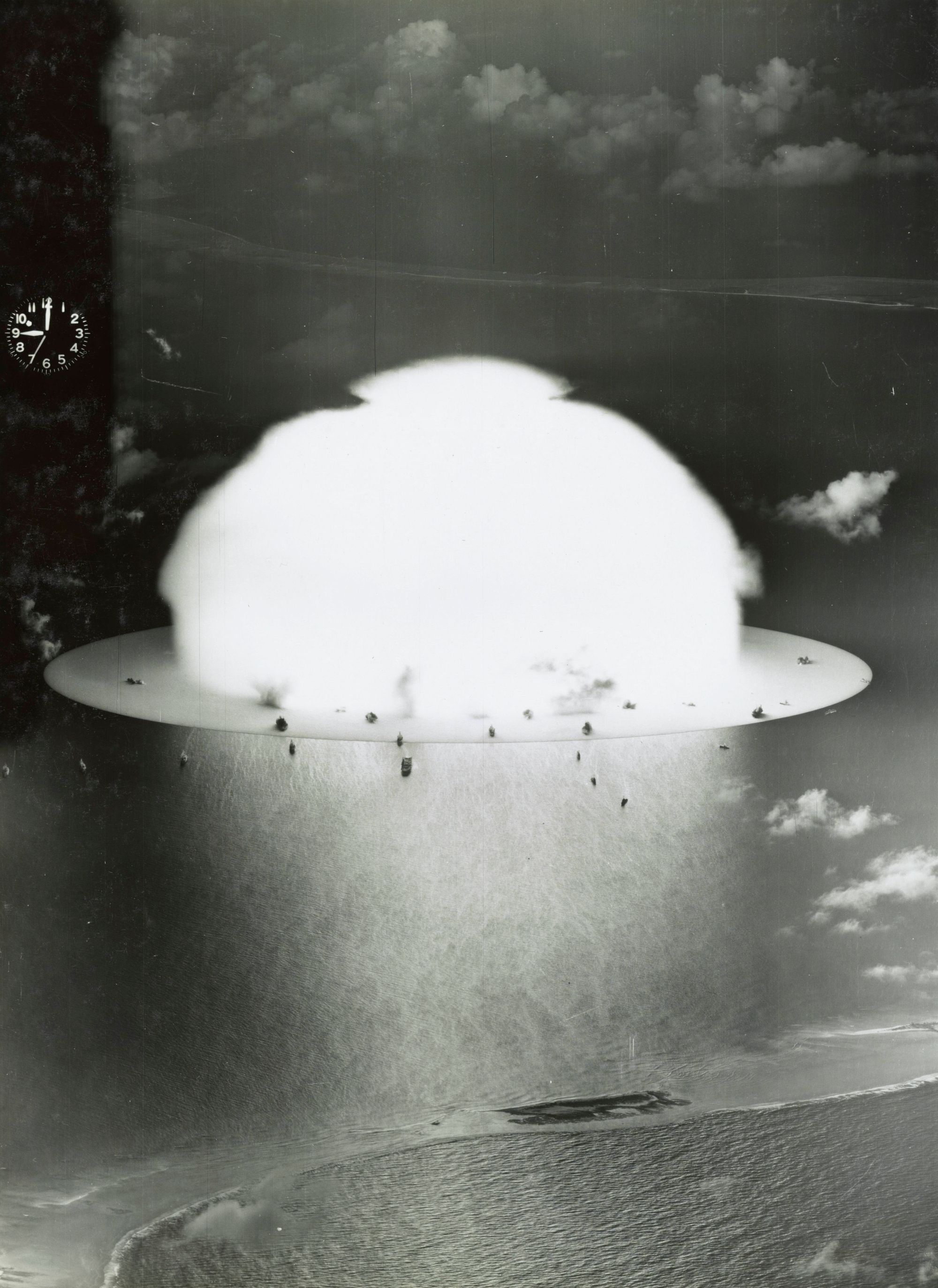

The word “atomic” became an adjective to describe something powerful and strong, not something murderous or genocidal. The Atomic Cocktail—-a potent mix of vodka, brandy, sherry, and champagne—became a popular drink in Las Vegas. And a daring women’s two-piece bathing suit was named after the Bikini Atoll, a test site in the Marshall Islands obliterated by atomic bombs. The psychiatrist Robert J. Lifton later came up with the term “psychic numbing” to explain the widespread refusal to face the reality of what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the threat of future catastrophe.

Similar messages were crafted to assuage the fears of children. “Duck and Cover” (1951), a civil defense film starring an animated character named Bert the Turtle, told kids that hiding under their desks at school could protect them from a nuclear blast. Popular comic book characters like Atomic Rabbit, Atomic Mouse, and Atom the Cat derived their powers from nuclear energy. “These were no atomic animal villains,” the historians Ferenc M. Szasz and Issei Takechi observed about the underlying themes of such comics. “Evil, it seems, would always be defeated by the proper use of atomic strength.” Astro Boy, a Japanese character in both manga and anime,also got his powers from nuclear energy but had a totally different sensibility. Astro Boy’s exploits often encouraged compassion, warned against blind faith in science, and sought the peaceful resolution of conflict.

Captain Marvel had a more nuanced view of nuclear issues than other American superheroes. At the end of “Captain Marvel Battles the Dread Atomic War” (October 1946), he told children, “I guess we’d all better learn to live and get along together… one nation with all the other nations… so that the terrible Atomic War will never occur!” In other comics, he supported the United Nations, questioned the safety of atomic energy, and saved the world from an “atomic fire.” But these increasingly subversive views were silenced by a lawsuit, filed by DC Comics, claiming that Captain Marvel too closely resembled Superman and violated copyright law. Captain Marvel ceased publication in 1953 and later returned for DC as a very different character. The following year, the United States detonated “shrimp,” a hydrogen bomb about one thousand times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. The new weapon created a fireball roughly four-and-a-half miles wide and contaminated an area of the Pacific Ocean more than one hundred miles wide with lethal radioactive fallout. And the Ferrara Pan Candy Company introduced the Atomic Fireball, a hugely successful new jawbreaker for kids. Sold for a penny from a carton decorated with a mushroom cloud, the candy combined cinnamon with capsaicin to produce a flavor that was “RED HOT.”

Perhaps the most disturbing atomic propaganda aimed at children was “Our Friend the Atom” (1957), an episode of the ABC television series “Disneyland.” Although the Disney comic book “Donald Duck’s Atom Bomb” (1947) was more blatantly in poor taste, “Our Friend the Atom” had the distinction of being hosted by a German scientist linked to medical experiments performed on inmates from the Dachau concentration camp during the Second World War. Heinz Haber, the host of “Our Friend the Atom” and author of the Disney children’s book with the same title, was a protégé of Dr. Hubertus Strughold, director of the Luftwaffe Institute for Aviation Medicine, whose physicians subjected hundreds of Dachau inmates to freezing cold temperatures and extreme pressure environments to observe how they’d respond. Inmates who survived the tests were usually killed and dissected. The Institute also placed mentally impaired children with epilepsy in a vacuum chamber and deprived them of oxygen, as part of an experiment to see if seizures could be induced.

After the war, Strughold and Haber were brought to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip. This top-secret program recruited German scientists with skills useful to the American military, regardless of their previous crimes against humanity. Strughold later became a professor at the U.S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine and Chief Scientist at the NASA Aerospace Medical Division. Haber became the chief scientific consultant to Walt Disney Productions—and the presenter of a television show urging American children not to be afraid of atomic power.

Although more widely known as a scholar, historian, sociologist, civil rights activist, and founder of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People, W.E.B. Du Bois was an outspoken proponent of world peace for more than half a century. He opposed the First World War, called for disarmament before the Second World War, and attended the San Francisco conference in 1945 that established the United Nations. He hoped that the UN would defend the human rights of every person, regardless of race, and finally put an end to the war. On February 16, 1951, one week short of his eighty-third birthday, Du Bois was handcuffed at a federal courthouse in Washington, D.C.—to embarrass and humiliate him, hardly to prevent an escape—and charged with failing to register as an agent of a foreign government. His alleged crime was heading an organization called the “Peace Information Center,” and he faced five years in prison for urging people to sign a petition that demanded “the outlawing of atomic weapons as instruments of aggression and mass murders of peoples.”

Not long after the Second World War, an opinion poll found that 54 percent of the American people wanted the United Nations to become “a world government with power to control the armed forces of all nations, including the United States.” The first resolution passed by the UN called for the banning of nuclear weapons, a position initially supported by President Truman. He also supported the international control of atomic energy. And then the Cold War began, the Korean War broke out, an anti-communist Red Scare swept the United States—and suddenly, it was considered deeply anti-American to be anti-nuclear. The title of a 1951 report by the House Committee on Un-American Activities made the point clear: “The Communist Peace Offensive: A Campaign to Defeat and Disarm the United States.”

W.E.B. Du Bois and his close friend Paul Robeson, the legendary actor and singer, thought the fight for civil rights within the United States was inextricably linked to the fight for Black liberation in colonial Africa—and opposition to all forms of militarism. Their views closely aligned with those being promoted by the Soviet Union. And both men soon paid a heavy price for their work on behalf of peace, racial justice, and anti-colonialism. The Justice Department claimed that the Peace Information Center was a communist front group bankrolled by the Soviet Union. When the case went to trial, the conservative judge who presided over it asked the government for evidence that Du Bois had received money from a foreign power—and when the government couldn’t provide any, the case was dismissed. But the damage had been done. The NAACP refused to support Du Bois, old friends abandoned him, and many Americans considered him a traitor. “Is it our strategy,” Du Bois asked, “that when the Soviet Union asks for peace, we insist on war?” Robeson posed a similar question: “Shall we have atom bombs and hydrogen bombs and rocketships and bacteriological war… or the peaceful construction of the good life everywhere?”

Robeson was blacklisted and unable to find work as an actor or a singer in the United States for years, as a result of his activism. And the State Department took away his passport, preventing him from working overseas, destroying his career. He later suffered from severe depression, attempted suicide, underwent electroshock therapy, and largely withdrew from public life. “The artist must take sides,” Robeson once said. “He must elect for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.” Du Bois had his passport seized, as well. When it was returned to him in 1958, he spent most of his time traveling outside the United States and eventually settled in Ghana. After the US Supreme Court refused to overturn restrictions on the political freedom of communists, he formally joined the Communist Party in 1961 as an act of defiance. The State Department revoked his passport again, and Du Bois died in exile two years later, at the age of ninety-five.

Over the years, when visiting Moscow, Robeson and Du Bois were welcomed like heroes and witnessed no racism. The lynchings, segregation, and Jim Crow laws in the United States encouraged them to have an idealized view of the Soviet Union, which publicly condemned all those things. But their vision of Soviet life was contradicted by reality. While attacking the United States for its nuclear weapons program, the Soviet Union secretly conducted espionage to launch its own, not only stealing the design of American atomic bombs but also copying the design of the principal American bomber to deliver them. While attacking the United States for its hydrogen bomb program, the Soviet Union secretly developed its own H-bomb. While demanding that the United States promise never to be the first to use a nuclear weapon in battle, the Soviet Union secretly adopted war plans that began with nuclear surprise attacks on American forces. Joseph Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union whom Robeson and Du Bois praised for his enlightened outlook, was responsible for killing more civilians than Adolf Hitler. And Soviet propaganda about civil rights was rendered absurd by the brutal violation of human rights throughout the Eastern bloc. During the Cold War, anyone who thought nuclear weapons posed a grave threat to humanity was caught in the middle of a rivalry between two superpowers determined to have them.

The Red Scare and the harassment of Robeson and Du Bois discouraged others from speaking out against American nuclear policies. But some people weren’t intimidated. “Fear is now the American way of life,” said an antinuclear pamphlet handed out by Dorothy Day, the radical Christian pacifist and co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, whose followers tried to emulate the selfless compassion of Jesus Christ. Day was arrested in New York City for refusing to participate in the 1955 Operation Alert civil defense drill. Instead of taking shelter, she and two dozen other protesters sat on benches in City Hall Park. “We will not obey this order to pretend, to evacuate, to hide,” her pamphlet explained:

In view of the certain knowledge the administration of this country has that there is no defense in atomic warfare, we know this drill to be a military act in a cold war to instill fear, to prepare the collective mind for war. We refuse to cooperate.

Day received a suspended sentence—but continued to protest the annual drills until they were ended in 1962, getting arrested four more times and spending a total of six weeks in jail.

Albert Einstein and the philosopher Bertrand Russell also spoke out against the nuclear arms race, carefully navigating the controversy surrounding the issue. Not long after Einstein’s death in 1955, their joint manifesto contained the memorable lines, “We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest… if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.” The following year, one of the most famous lines in twentieth-century poetry appeared in “America,” Allen Ginsberg’s beat rant against Eisenhower era conformity: “Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.”

Fears of the radioactive fallout from nuclear weapon testing, which traveled many thousands of miles from test sites, inspired an antinuclear movement among largely white, middle-class Americans in the late 1950s. The National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) attracted a liberal membership, in part, by banning Communists from becoming members. Folk singers began to include songs about the nuclear threat in their live sets—most memorably Bonnie Dobson’s haunting, post-apocalyptic “Morning Dew” (1962), later covered by the Grateful Dead, and “Take Back Your Atom Bomb,” written and sung by Peter La Farge, a rival of Bob Dylan in the New York City folk scene who mysteriously died young. James Baldwin and Martin Luther King became prominent supporters of SANE, carrying on the tradition of Robeson and Du Bois, stressing the connection between civil rights and disarmament. “I don’t think the choice is any longer between violence and nonviolence in a day when guided ballistic missiles are carving a highway of death through the stratosphere,” King said in 1961. “I think now it is a choice between nonviolence and nonexistence.”

The United Kingdom, thanks to its high population density, was especially vulnerable to a nuclear attack. A top secret study in 1955 found that ten hydrogen bombs, detonated on the west coast of the UK, would blanket the entire nation with radioactive fallout and render most of the nation’s farmland too dangerous to use for months. A few years later, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) led thousands of protesters on a fifty-mile march from Trafalgar Square in London to the British nuclear weapons factory in Aldermaston. In preparation for the march, the artist Gerald Holtom designed a symbol for the anti-nuclear movement. “I drew myself,” Holtom recalled, “the representation of an individual in despair, with palms stretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad.” He placed a circle around the self-portrait, an elongated stick figure, and created an image later known as the peace sign.

“The H-bomb’s Thunder,” written for the Aldermaston march by the science fiction novelist John Brunner, became the theme song of the CND. After waning in popularity during the late 1960s, the antinuclear movement experienced a resurgence a decade later, with a very different musical vibe.

A pair of anarcho-punk bands provided the CND’s soundtrack during the Thatcher era: Poison Girls, headed by Vi Subversa, a mother of two in her early forties—and Crass, whose “They’ve Got a Bomb” featured seventeen seconds of silence mid-song, representing the moments after a nuclear detonation.

Ben Shahn’s “Stop H-bomb Tests” (1960) was created as a poster for SANE, and its simplicity prefigured the pop art that would soon dominate New York galleries. Over a decade, Shahn made a series of drawings, posters, and paintings about the nuclear threat. “We are living in a time when civilization has become highly expert in the art of destroying human beings and increasingly weak in its power to give meaning to their lives,” Shahn said. Roy Lichtenstein’s “Atom Burst” (1965) resembled a panel from a comic book like “Only A Strong America Can Prevent Nuclear War! (1952), though more light-hearted and ironic. Andy Warhol’s art was notable for its clean, detached, striking design, not its emotional or political content. But his silkscreen painting “Red Explosion [Atomic Bomb]” (1965) defies that description, presenting five rows of five mushroom clouds, rendered in black and red, that become increasingly darker and more ominous. There is nothing coy, detached, kitschy, or amusing about the painting. It was exhibited for the twentieth anniversary of Hiroshima’s destruction, which happened to fall on Warhol’s birthday.

In 2014 the artist Smriti Keshari and I decided to create a multimedia installation about nuclear weapons. Smriti had recently seen “Massive Attack V Adam Curtis”(2013) at the Park Avenue Armory, an immersive combination of archival footage and live music. I had spent years researching the science, culture, and technology of nuclear weapons for my book Command and Control (2013). And we’d both been transfixed by Bruce Conner’s “Crossroads” (1975) at the Museum of Modern Art, a film that simultaneously conveyed the horror and strange beauty of nuclear detonations. We wanted to remind people of a threat that had been largely forgotten, to surround them with images, bombard them with sound, put them in the middle of the nuclear madness, and provide them with a visceral, unsettling experience. We were helped immeasurably by Kevin Ford, a filmmaker and editor; Stanley Donwood, the artist responsible for Radiohead’s visuals; Ben Kreukniet, a designer at United Visual Artists; Kingdom of Ludd, an animator; and the Acid, an electronica band comprised of Ry X, Adam Freeland, Steve Nalepa, and Jens Kuross. The installation, called the bomb, premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2016 and has been subsequently staged in Berlin, Oslo, Sydney, Glastonbury, and Washington, D.C. Whatever you think of the piece’s artistic merit, without lecturing, hectoring, or resorting to agitprop, it’s our attempt to take sides.

Support for the antinuclear movement has ebbed and flowed over the years, driven by world events, the prominence of other issues, the perceived level of risk. The signing of arms control treaties in the 1960s and protests against the Vietnam War diverted attention from the nuclear threat. The election of Ronald Reagan and a renewed arms race between the superpowers galvanized mass demonstrations throughout the world. In 1982 an opinion poll found that more than half of the American people feared that President Reagan would involve the United States in a nuclear war. During that era, I remember thinking that a nuclear attack could come at any moment, that the world might literally end without warning. Far from being irrational, we now know that such fears were grounded in reality. Recently declassified documents reveal that Abel Archer, a large-scale military exercise conducted by the United States and its NATO allies in November, 1983, was misinterpreted by the Soviet Union. It thought Abel Archer might be a cover for a nuclear surprise attack. Soviet ballistic missiles were put on high alert, ready to be launched within three minutes. The exercise ended peacefully—without the United States realizing that its practice drill had almost caused the real thing.

Today the threat of a city being destroyed by a nuclear weapon is extraordinarily high. The rise of racism and nationalism worldwide, the new arms race between the United States and Russia, the nuclear rivalry between India and Pakistan, the border skirmishes between India and China, the emergence of North Korea as a nuclear power, the nuclear ambitions of Iran, the possibility of terrorists obtaining a nuclear weapon, and the unpredictable behavior of world leaders like President Donald Trump have greatly increased the danger. According to the Doomsday Clock created by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a symbolic measure of the threat, we are only one hundred seconds from midnight—the closest the world has come since the 1940s. And yet remarkably little attention is being paid, as doomsday grows closer and closer.

A new anti-nuclear movement has emerged to confront the new nuclear threat. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) has in many ways reframed the argument, denying that these weapons are symbols of national strength and stressing the humanitarian consequences of their use. Beatrice Fihn, the executive director of ICAN, considers nuclear weapons the ultimate form of toxic masculinity. “White men in ties discussing missile size” is how one feminist scholar described the making of nuclear policy. International law prohibits the deliberate targeting of civilians—and yet that’s pretty much all nuclear weapons are good for. Precision weapons using conventional explosives can now destroy just about every possible target without much collateral damage. International treaties have banned landmines, cluster munitions, chemical weapons, and biological weapons because they may indiscriminately harm civilians. “You’re not supposed to target civilians under the laws of war, you’re not supposed to wipe out whole cities,” Beatrice Fihn argues. “But we justify nuclear weapons, and that doesn’t make any sense.” Even a relatively small-scale nuclear war between India and Pakistan—using a few hundred weapons much less powerful than those deployed by the United States and Russia—would kill perhaps one billion people.

ICAN was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, and a UN treaty sponsored by the group has been ratified by forty-three countries. The treaty would ban the development, testing, production, use, and threat to use nuclear weapons. If seven more countries ratify the treaty, it will become international law. Fihn hopes that will happen by the end of 2020. She considers the antinuclear movement to be part of a broader fight against racism, sexism, inequality, militarism, climate change, and war. She has no illusions that passage of the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty will immediately usher in an age of peace, love, and understanding. But it will mark a step forward, help shift the conversation, stigmatize unacceptable behavior by nation-states. Most of all, Fihn says, it will be “the starting point, you know, for the end of nuclear weapons.”

Some of the most powerful art about nuclear weapons has been created by those who experienced them firsthand, people whom the historian John Dower called “The Bombed.” The hardships endured by hibakusha, the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, almost defy words. Many suffered severe injuries and lasting illnesses. They received neither financial aid nor medical treatment from the American occupying army, local officials, or Japan’s government. They were considered tainted and contaminated by other people in Japan, who shunned them and their children. And for almost seven years, they were silenced by American censorship. “With but rare exceptions, survivors of the [atomic] bombs could not grieve publicly, could not share their experiences through the written word, could not be offered public counsel and support,” Dower wrote. But their plight enabled Japanese leaders to promote a sense of national victimhood and avoid acknowledging or reckoning with the “Asian Holocaust”—the roughly 10 to 15 million civilians, mainly Chinese, that the Japanese military killed with chemical, biological, and conventional weapons during the Second World War.

The opening of Nakazawa Keiji’s autobiography matter-of-factly describes the events that inspired Barefoot Gen (1973 to 1985), his ten-volume manga classic set in Hiroshima and the anime adaption of it (1983, 1986):

August 6, 1945. I was a first-grader. That morning I was at the wall that enclosed the school, talking with the mother of a classmate who had stopped me when the atomic bomb fell. She died instantly. I was pinned beneath the wall and survived miraculously.

Of my family, Dad, older sister Eiko, and younger brother Susumu died that day...

Mom, too survived, but from then on, her health was fragile from the aftereffects of the bomb. [Her] baby was born into that horror right after the bombing and died soon after birth of malnutrition.

I lost Dad, Eiko, Susumu, and the baby in the atomic bombing and went to live with relatives, where I was treated as an “outsider.”

Barefoot Gen tells the story of a young boy, much like Nakazawa Keiji, who lives through the destruction of Hiroshima and fights to survive in the city’s ruins. It does not flinch from depicting the horrors of the bombing and its aftermath, the struggles of orphaned children, the discrimination faced by the hibakusha, and the brutal crimes committed by the Japanese military during the war. Like John Hersey’s Hiroshima, it is ultimately life-affirming, as Gen, the young protagonist, regains his hair, remembers his father’s words, and vows to persevere. Nevertheless, Barefoot Gen has been banned from some Japanese public schools and attacked by conservatives for being an “ultra-leftist manga that perpetuated lies and instilled defeatist ideology in the minds of young Japanese.”

Iri and Toshi Maruki arrived in Hiroshima a few days after the bombing, hoping their friends and relatives there had survived. The Marukis were a married couple, both artists, one an oil painter, the other a practitioner of traditional Japanese ink painting. Here is their description of what they found:

We lost our uncle to the atomic bomb. Two young nieceswere killed. Our younger sister suffered burns, and our father died after six months. Many friends and acquaintances perished… Just over two kilometers from the center of the explosion, the family home was still standing.

But the roof and roof tiles and windows were blown away by the blast, along with pans, bowls, and chopsticks from the kitchen… large numbers of injured people had gathered there and lay on the floor from wall to wall. We carried the injured, cremated the dead, searched for food, and found scorched sheets of tin to patch the roof. With the stench of death and flies and maggots all around us, we wandered about just as those who had experienced the bomb.

After returning to Tokyo and recovering from radiation sickness, the Marukis felt compelled to depict the scenes they’d witnessed in Hiroshima.

Pika-don (1950), a collection of the Marukis’ black-and-white drawings, gave perhaps the first visual representation of atomic bomb victims permitted in Japan. Five large murals they’d made, depicting the carnage in Hiroshima, were soon exhibited in Tokyo and Kyoto, causing a sensation. About six feet high, composed of eight panels extending for about twenty-four feet, created with ink, charcoal, pigment, glue, and conté crayons, the murals were viewed by about a million people within the first two years. In a representational style evoking the work of Kathe Kollwitz, a German expressionist and pacifist, the Marukis depicted bodies consumed by flames, survivors desperate for water, the corpses of children heaped along a riverbank. The murals offered a daring criticism of America’s use of the atomic bomb. Over the next three decades, the Marukis created another ten murals, known collectively as the Hiroshima Panels, broadening their critique to include atrocities committed by the Japanese during the Second World War—and alienating many who’d celebrated the early focus on Japanese victims. Six of the panels were exhibited at Pioneer Works in 2015. Although not as well-known as Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), the Hiroshima Panels are a similarly monumental work that fuses art and activism and righteous anger at the needless slaughter of civilians.

In recent years, Eve Andréé Laramée, Pedro Reyes, Michael Koerner, Lovely Umayam, Kayla Briët, Shiva Ahmadi, and others have created provocative works of art that address the nuclear issue. We need more.

and if you’d like to know more...

For more reading about the legacy of the atomic bomb, tune into the six-part limited podcast featuring interviews with prominent figures in the nuclear deterrent movement.

Subscribe to Broadcast