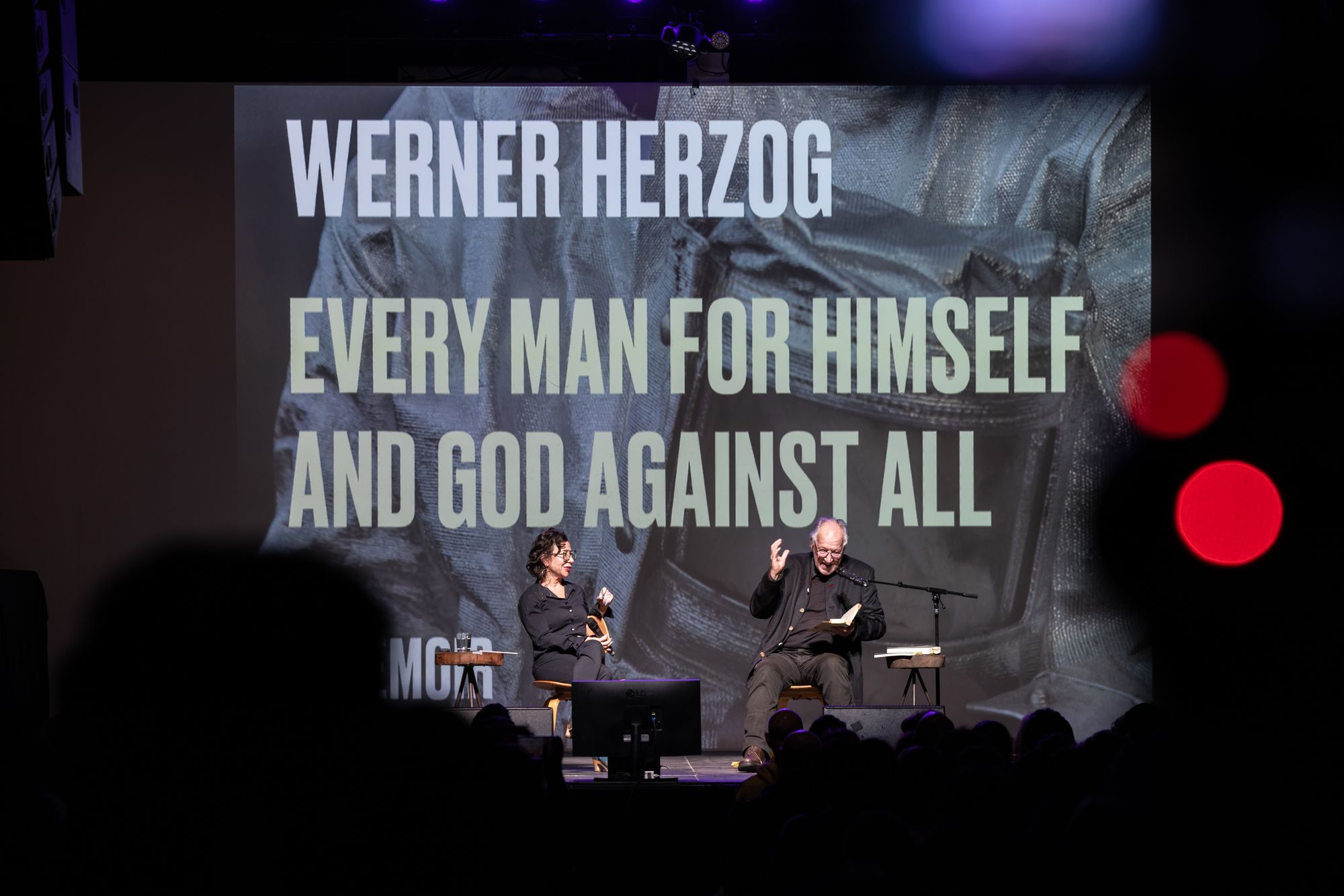

Werner Herzog Is A Poet (And He Knows It)

Werner Herzog holds the young Brooklyn audience in total thrall. They stare in silence as the iconic German filmmaker performs a pristine rendition of Werner Herzog-ness, and erupt in near-horny giggles whenever they think he might be telling a joke. This ambiguity is key to Herzog's seductiveness—the sense that he's always, at once, being dead serious and playing a funny little game.

Herzog seems to find almost everything profound—tragic and funny, in equal parts—and he has a unique gift for transmitting that feeling to audiences. This, in his own estimation, comes down to his writing. He wants to be considered an author, first and foremost, he says. The films that made him one of modern cinema’s greatest arthouse directors are mere distractions at this point. “I am a poet,” he concludes, and it’s totally beside the point whether or not he’s joking.

This is, among other things, a hell of a way to promote your new memoir. In Every Man for Himself and God Against All, Herzog commits a semi-novelized account of his life to paper, offering the most distilled look yet at what’s going on in his head. One of the recurring tenets of his story is a belief in the innate cruelty of nature. His work, he says, has been an effort to wrestle with this haunted order and perhaps to make peace with it, temporarily, in images and on the page.

What does it mean to believe that the natural world is out to get us, and how has this notion informed Herzog’s work? Our own Janna Levin sat down with him at Pioneer Works to find out.

— Leon Dische Becker

Werner has made over 80 films. So imagine my surprise when last weekend he emailed me, saying, "I don't want to talk about my films." And then in that same email, he also said, "I don’t want to be interviewed." So this whole thing is going to be very interesting.

I am trying to get across that I'm a writer as much as I'm a filmmaker. I have a formula; filmmaking is like my voyage, but writing is home. I reject the whole premise of this evening completely, but for your sake I'll go along with it.

Since I was given instructions not to discuss your films, I'll discuss Les Blank's documentary Burden of Dreams instead, which chronicles the production of your 1982 film Fitzcarraldo. There’s a famous monologue in which you say nature is “not harmony but chaos, hostility, and murder.” Can you elaborate on why you feel that way?

You don't need to be a scientist to look up and see the mess, and how very dangerous and hostile it is out there. You don't need to have any schooling at all. You know it. You can tell. I delivered that monologue for Les after two of our planes crashed and our camp was attacked and burned down during a border war between Peru and Ecuador. Three people that were fishing for us were also attacked by a tribal group that lived up in the mountains. The tribe shot one of our men with a gigantic arrow, something like six feet long with razor sharp bamboo tips. They shot him through the throat, and he survived. And then a woman was hit in the abdomen by three arrows. One broke inside her pelvis and one went through her body next to the kidneys, then one was deflected from the hip. We had to operate on them on the kitchen table. They would have died if we had tried to transport them. Two days later, Les asked me, "Speak about nature."

There are two parallel things going on. One is, you're trying to make this film, but you're also actually living the film. It's not CGI, it's not a little model. You are actually engineering solutions, which you worked on daily.

It's all my life, the memoirs as well. That's why it's easy to write, because…

…you lived it. But I think the response you give Les—just raw, in front of the camera—is beautiful. You seem stripped and vulnerable, and speak completely naturally about the work, in a way that I think represents what we're discussing tonight: that you see yourself as a writer and you have been writing this incredible prose all along. You say, "Everyday life is only an illusion, an illusion behind which is the reality of dreams. It's not just my dreams, it's my belief that all these dreams are yours as well. The only distinction between me and you is I can articulate them. I make films because I have not learned anything else. It's my duty. This might be the inner chronicle of what we are, and we have to articulate that. Otherwise, we are just cows in the field." And I think that this is a beautiful segue to a passage in Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo—which was essentially your diary during that time—where you address those feelings again.

Well, it has to do with an anti-romantic view of nature, of the environment. It was written back in 1981, when we were filming Fitzcarraldo, and I made a film on [Klaus] Kinski and our collaboration. I met some men who long before had offered to kill Kinski for me, which I declined; I still needed him for work. I was at this small village in the jungle.

"It was midday, and very still. I looked around, because everything was so motionless. I recognized the jungle as something familiar, something I had inside me, and I knew that I loved it: yet against my better judgment. Then words came back to me that had been circling, swirling inside me through all those years. Hearken, heifer, hoarfrost. Denizens of the crag, will-o'-the-wisp, hogwash. Uncouth, flotsam, fiend. Only now did it seem as though I could escape from the vortex of words.

Something struck me, a change that actually was no change at all. I had simply not noticed it when I was working there. There had been an odd tension hovering over the huts, a brooding hostility. The native families hardly had any contact with each other, as if a feud reigned among them. But I had always overlooked that somehow, or denied it. Only the children had played together. Now, as I made my way past the huts and asked for directions, it was hardly possible to get one family to acknowledge another. The seething hatred was undeniable, as if something like a climate of vengeance prevailed, from hut to hut, from family to family, from clan to clan.

I looked around, and there was the jungle, manifesting the same seething hatred, wrathful and steaming, while the river flowed by in majestic indifference and scornful condescension, ignoring everything: the plight of man, the burden of dreams, and the torment of time."

I was so moved by the idea that you were living this experience, not as a distant observer or trying to summarize things theoretically or hypothetically, through books. But you were actually going right in and experiencing it. And so much of your [new] memoir is a broken nose and a busted lip, and you're about to fall into a ravine, and then something catches fire. And it's almost as though you're hurtling into the most extreme of experiences. You go to Antarctica, you go to the precipice of an active volcano. You go to the furthest reaches of the Earth.

It kind of sounds sexy, "I'm going to Antarctica." You know what? When you're at McMurdo Station in Antarctica there's an ATM machine, and there are abominations like aerobic studios and yoga classes. It's not like in Shackleton's time.

Of course I have done risky things. The photo [on the memoir’s cover] is from not long ago; I was on a volcano in Vanuatu, in the western Pacific, with a very competent volcanologist. And we put on these fireproof suits, and we went very, very close to the crater, because it looked alright—but they are unpredictable. All of a sudden we were too close: a massive ejection of glowing slabs rained on us. So you better flee. You flee, because you’re a professional. I do not expose myself to these things. It was good for the images, and it was good for the texts that I wrote. But of course, there are certain risks, yes.

I do think that there is this sense that your very unusual experience growing up forced you to become expert in a variety of survival tactics, that other people were maybe coddled out of.

Well, yes. I was born while the war was still going on, and then in particular the postwar years.

In Munich?

No, not in Munich. It was bombed out when I was two weeks old, everything was destroyed, and the place where we lived was ruined. My mother found me in my cradle under a thick layer of glass shards and debris. I was completely unhurt, but she got scared and fled with my older brother and me [to Sachrang]. So we were refugees in the remotest mountain valley you can imagine. We grew up without running water; we had to go to the well with a bucket, and we had only an outhouse as a toilet. We had no sewage system or electricity, and snow drifts would come in.

Sometimes, to make a mattress, my mother would cut ferns and dry them like hay. But ferns, of course, somehow condense when you lie on them, and when you cut them they make these stems that are sharp like a sharpened pencil. So they would sting you at night, and form some sort of undulating surface. For 11 years I never had a flat bed. I had to sleep somehow. And of course we were starving. We were very hungry.

You say literally, and this is a quote, "It was the most wonderful childhood."

It was, yes. And all the children who grew up in the bombed-out cities say exactly the same thing. It's where children were kings of bombed-out blocks, and there were no fathers around—no drill marshals who would tell them how to behave. Some of my strongest childhood memories are of my mother. Maybe I can read some of those.

She had higher degrees, and your father, too.

She had a PhD, and my father as well, but…

They were intellectuals, and scientists.

Biologists. But because she was Dr. Herzog, the peasants believed she was a medical doctor. And in emergencies, they would call for her.

So she was at a loss.

For example, a four-year-old child reached up to a pot on the stove in their farmhouse, toppling it. Boiling water went from his chin all over his body. When my mother arrived the boy was dead. His heartbeat had stopped. My mother, as solid as she was, injected—I think adrenaline or whatever—between his ribs and right into his heart muscle. The boy survived.

And bearing in mind that she had absolutely no medical training, but just rose to the title.

You had this passage…

Yes, I would love for you to read it. I have it here. This really moved me, when you are talking about your mother very early on.

All right.

"My older brother Till and I grew up in extreme poverty, but we never even knew we were poor except perhaps in the first two or three years after the end of the war. We were simply always hungry, and my mother was unable to produce enough food for us. We ate salad from dandelion leaves; my mother made syrups from ribwort, and fresh pine shoots; the former was more of a house remedy for coughs and colds, the latter stood in for sugar. Once a week, there was a longish loaf of bread from the village baker, purchased with one of our ration coupons. With a point of a knife, our mother scratched a mark in it for each day, Monday to Sunday, allowing about a slice of bread for each of us. When hunger got to be very bad, we were each given a piece from the next day's ration because my mother hoped something might turn up in the meantime. But generally, the bread was finished by Friday, and Saturdays and Sundays were particularly bad. My deepest memory of my mother, burned into my brain, is the moment when my brother and I were clutching at her skirts, whimpering with hunger. With a sudden jolt, she freed herself, spun round, and she had a face full of anger and despair that I have never seen before or since. She said, perfectly calmly, 'Listen, boys. If I could cut it out of my ribs, I would cut it out of my ribs, but I can't. All right?' At that moment we learned not to wail. The so-called culture of complaint disgusts me."

It's tremendous in so many ways, this sort of resilience that your mother is teaching you, almost unintentionally. It's just who she is.

We had to learn it ourselves. We re-educated our mother, who grew up in a regular household where she never had to starve. But we had to invent our toys, we had to invent our games. Although the valley where I grew up was idyllic, there was nothing like romanticism. And it's very strange, because sometimes reviewers of my films, or of my books, try to put me on some sort of a shelf, in some sort of order. And they keep saying, "He's in the tradition of German romanticism." No, I am not. And there's proof after proof after proof in my writing. For example, in Conquest of the Useless, my description of nature—of the jungle—is really harsh and stark.

So what I'm doing with my writing and filmmaking is dealing with whatever is being thrown at me. I will deal with it like a soldier, with a sense of duty. So don't worry about that. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast