Bad Mind Music

Bass(less) Culture

Perhaps it is in the nature of cultural commentators to glorify or even romanticize the youthful period in which they first found their voice. Thus it is that when I found myself unexpectedly living in Jamaica, a COVID refugee at the start of 2020, I was shocked as an old school reggae lover by the change I heard in Jamaican music. What, no bass?

When I first landed in Jamaica from London in the mid ‘70s, I was in thrall to dub and classic “one drop” reggae: the music’s low end was a fetish. Rounded and resonant, reggae bass was amplified by “sound systems” in the street to roaring melodic thunder; speaker stacks were designed just for it. The instrument was defined as the soul of global reggae culture, and that of Black Britain in particular, when the great dub bard Linton Kwesi Johnson described what bound a generation as Bass Culture.

Coming from leafy Hampstead, I had lucked into living in London’s Bass Culture country, in loucher Ladbroke Grove. Known for London Carnival—the biggest street party in Europe—it was also home to a number of all-night reggae dance parties in firetrap abandoned properties called shebeens, which provided me with a great social life for a long time. In addition, I found myself briefly working as the publicist for Bob Marley and the Wailers, and then covering Bob as a music journalist, learning from his commitment, compassion and ferocious work ethic. He became a mentor and set a high bar for the connection between music and activism—his message always powered by that propulsive bass—in Bob’s case, coming courtesy of Aston “Family Man” Barrett. Fams had mentored Robbie Shakespeare, known for his work with Sly and Robbie, Jamaica’s session rhythm powerhouse. But both “bassies” have recently died—with Fams’ passing this winter, I felt the era of bass-heavy “conscious” reggae fading further into the past.

When reggae was my religion, during the 1970s, I became part of a generation that benefited from a sort of reverse cultural colonialism which followed the colonies gaining Independence. The sounds of the Empire’s former subjects ruled us all—a process furthered right now by the global dominance of Nigerian Afrobeats. But back when I was staying at Hope Road, reggae’s international market was exploding. Famously, oil-flush Nigerian customers would turn up at Virgin Records’ offices in London with suitcases of cash to buy up wax of U Roy or The Mighty Diamonds. Pivotal was the ascent of Bob Marley.

In Jamaica in 1976 for Virgin’s Front Line label, I overstayed my hotel tab and Bob kindly invited me to stay at his home in uptown Kingston. An ample mini-great house of the late colonial era, the communal space on Hope Road––now the Bob Marley Museum— offered the dynamic theater of people constantly dropping in from all classes and social circles—uptown, downtown, and those like myself, “from foreign.” Marley had spent his own boyhood in one of downtown Kingston’s impoverished ghettos; and was now determined, he told me, to “bring the ghetto uptown.” He continued deliberately, “You have to show people some improvement. Not necessarily materially, but in freedom of thinking.” The day after I left for London, gunmen burst in and tried to kill him, wounding two others and leaving a bullet in Bob’s arm that stayed there until his death. I’ll never forget arriving to the rock paper where I worked, the morning after I flew home, and seeing the shocking news on the telex: “reggae singer shot”—in the bustling commune I had just left.

The author displays the only extant photo of her, taken by Kate Simon, with Aston “Family Man” Barrett and Bob Marley, as printed in her 2006 work, The Book of Exodus.

Photo: Alexesie PinnockNow, the period leading up to and following this assassination attempt—a period when Bob fled Kingston for London, and I had a front-row seat for the recording of his great 1977 album Exodus––is the subject of a big-budget movie. The release of One Love is another reason my mind has been returning to those formative days, and contemplating how the new sounds of Jamaica’s streets they resonate with these even tougher times.

AudioMack playlists blasting, I’ve spent much time since 2020 cruising around the island, with my friend Alex, a 27-year-old photographer steeped in current island music and always searching for new sounds. I was surprised at the noisy vacuum left in these hot new tunes by the absence of what we lovers of “one drop” reggae treasured most—the bass. More unsettling still, this bass-less genre seemed to dwell on the "bad mind," malicious backstabbers who smile in your face while plotting your downfall; it was more nihilistic than emo. While Jamaican music has evolved in countless ways since the ‘70s, the shift from that era’s conscious “roots” sound to the faster, rougher dancehall styles of the 1980s and ‘90s didn’t involve quieting the music’s low end. In today’s dancehall records, by contrast, the bass is a ghost of its old self, suggested by a low drone or irregular pulse, if at all.

But as it often goes with new sounds, after a while I started to adjust to and even enjoy the thinner, tinnier music, despite its excessive use of vocoder. I was struck by three artists in particular. Rygin King lured me with plaintive tracks like “Song Cry,” and “Broken,” sung from the wheelchair he’s used since he was paralyzed by gunfire at a show. Then there was Shane-O. His anthems like “Dark Room,” “Wicked People,” and “Hold On,” tuneful, heart-stabbing evocations of loneliness and angst, namecheck “bad mind boys,” yet suggest, with surges of female harmonies, how they might survive seemingly impossible obstacles and live to hit a higher note.

Chief in this new crew was Rebel Sixx, aka Kyle George—a prime purveyor of the new “Trinibad” dancehall sound, who I learned was not Jamaican but Trinidadian: a Trini from the southern Caribbean island known as the wellspring not of reggae but cheerful, friendly-sounding calypso and soca. Rebel’s cynical poignancy on “No Trust No Love,” sung with Travis World, reeled me in. It was a breath-stopping shock when I heard that he was already dead at 26; his ironic soprano was reaching me from the grave. I was determined to learn more about his fate.

*

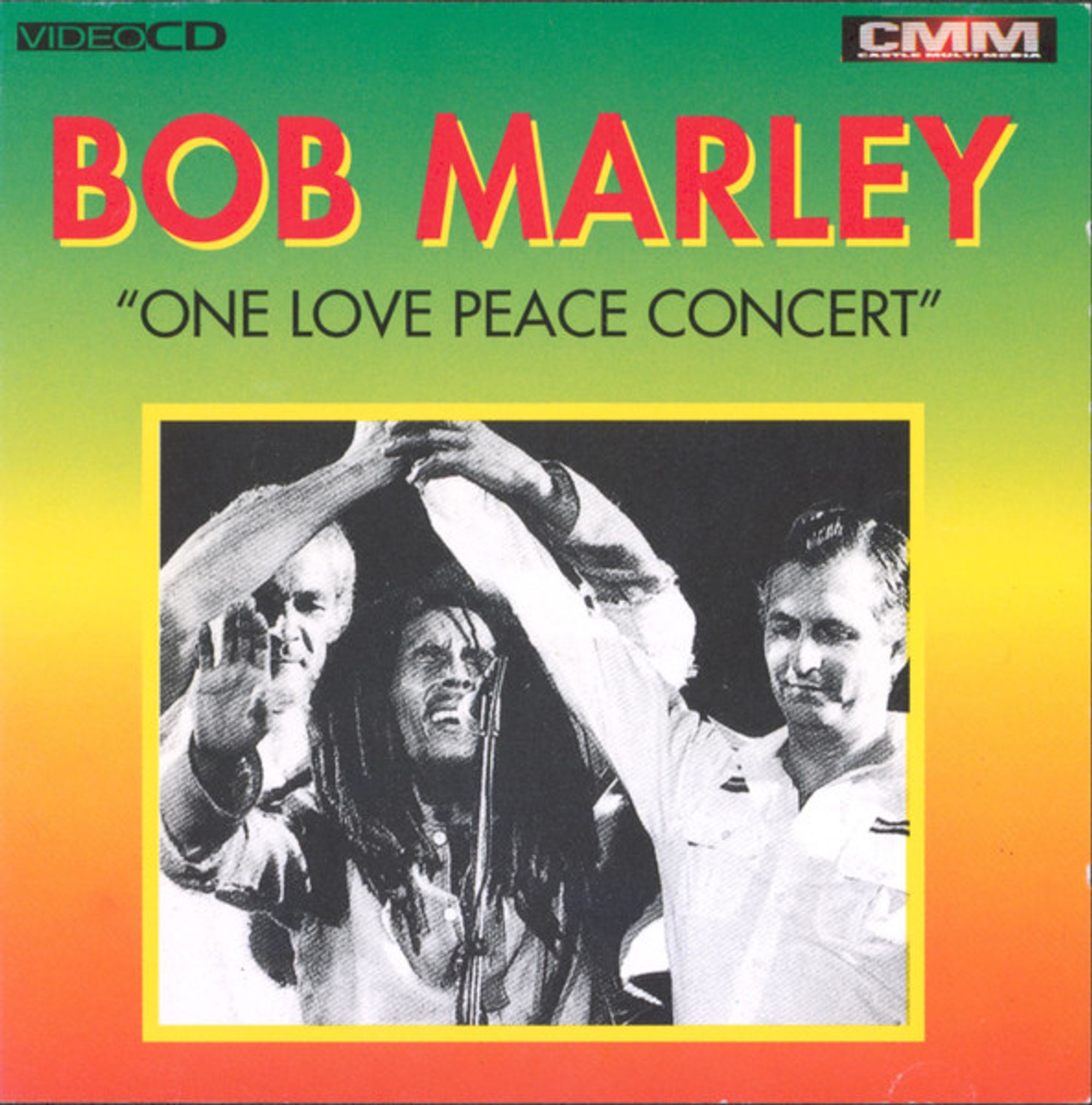

My need to find out more about Rebel Sixx’s story was propelled, no doubt, by events I lived five decades ago, and that I later chronicled in my Book of Exodus—an account of the attempt on Marley’s life, his escape to London where he made Exodus, and his return to Jamaica 18 months later for a historic peace concert.

The idea for the concert was hatched by two rival dons—as the gangster-bosses of Jamaica’s “garrisons,” or impoverished neighborhoods shaped by political patronage, are known here—who found themselves in the same jail cell. Claudie Massop and Bucky Marshall connected the dots to see how, as neighbors and enemies, they had been manipulated into trying to kill each other. Both “bredren” of Marley’s, they called on Bob to risk returning to the island and playing a “One Love Concert” for peace—and he paid for their tickets to come to London to discuss it.

In the mid-1970s, the loyalties of Jamaica’s two-party system were clearly aligned with Cold War interests. The Peoples National Party (PNP), headed by the glamorous Michael Manley, was involved with Castro’s Cuba and Russia, whereas the Jamaican Labour Party (JLP) headed by Edward Seaga (also known as a record producer and student of African rituals) was tucked in bed with America. Kingston neighborhoods like Marley’s Trenchtown (a PNP garrison) and his childhood friend Claudie Massop’s Tivoli Gardens (a JLP stronghold) were warring no-go zones whose residents could not cross into neighboring streets. The strings of the puppets performing gang warfare in the rundown ghetto were being pulled from far away, but the bullets and killings were real.

So the dons’ initiative was bold: an attempt to throw off the political shackles that were holding Jamaica’s poor captive. The exhilaration of the Peace Concert, and the Rasta drums that throbbed through the city all night, will always stay with me. The music was magnificent and a joy for bass fans. Robbie Shakespeare brandished his bass like a spear as he backed Peter Tosh, and the inimitably rounded notes of Family Man’s instrument anchored Bob’s Wailers. Bob called the rival political leaders to the stage and made Manley and Seaga clasp hands over his head. Mystically, and as if by sympathetic magic, lightning flashed, thunder rolled, and the moon shone red above their heads. The truce may have only been theater, but the image was indelible.

Deep in the throng pressing against the stage, I was entranced and permanently infused with the idea that music can bring about change––even as I fought off someone trying to steal my cassette player. The Peace Concert of 1978 has stood since as a beacon of possibility for those who believe that artists have a role in bringing change to their community and the world.

In the weeks after the concert, Bob’s friend Claudie Massop was just one of the peacemakers killed by the police. There was a widely-held rumor, often now mentioned as fact, that one of the political parties smuggled guns inside the sound equipment brought in from the States for the show. The undercurrent of violence simmered beneath the release of peace, even then.

Nowadays in Jamaica, the PNP-JLP rivalry persists. The murder rate is still formidable. Around the world, as in Jamaica and the wealthier island of Trinidad, the sway of powerful gangs has grown in recent decades, with all the gangsterism that implies. With COVID and its repercussions intensifying the mix, all these elements shake up into today’s toxic “Bad Mind” cocktail, arguably even more lethal than when Bob got shot.

Bad Mind

Must they always kill the best and brightest, or try to? Rebel Sixx foretold his demise in music, like Tupac and Biggie. But his murder, for me, reverberated with Marley’s narrow escape and the death of the Wailers-style bass—killed by changing tastes and technology. Somehow the bass came to represent not just a sonorous absence, but an absence within what I’ve come to think of as the Bad Mind movement––that sense of militant, against-all-odds, revolutionary optimism, which few of this popular generation of artists seem to feel. In the old conscious reggae crew, Bob Marley was not the only one to leaven his most dire critiques of humanity with enough hope to keep you going. Bad Mind music is the offspring of a generation several times removed from Bob’s. They were raised on digital music amid the drip of trickle-down financial policies and the chasm of the economic gap.

Before the island won independence in 1962, Jamaica’s music was the mellow, folk-y lilt of mento, which sped up to the urgent scurry of ska in the 1960s, inspiring Britain’s lauded 2-Tone movement—The Specials, Selecter—and a worldwide community that still flourishes today. Live DJs equipped with giant sound systems—“toasting” over twelve-inch disco mix records at Kingston street dances—are generally acknowledged as being forerunners of American hip-hop. Conscious reggae was spearheaded by the leonine Bob Marley, while the masters of dub, its ghostly sister, turned the studio into a tool for crafting records from a post-modern collaging of echoes and beats. Both were grounded in classic organic rhythm sections of bass and drums, until the rise of synthesizers and other digital tools eliminated the need, for many music makers, to play live instruments at all.

The big shift came with Wayne Smith’s “Sleng Teng” in 1985, an iconic hit whose reedy, sugar-high Casio loop was designed by a Japanese woman, Okuda Hiroko, and tweaked for reggaematic purposes by the producer Prince Jammy. After that, the deluge of synthesizers, along with an increase in guns and cocaine on the island, saw the music become ever more crude, urgent, and violent. Dancehall went on to be the impetus for the Latinx reggaeton sound. Born in Puerto Rico and elsewhere of Jamaican parents, reggaeton dominated many of the world’s dancefloors until Afrobeats emerged from the motherland, Nigeria specifically, a few years back. All these post-digital sounds share the bass-lessness of Jamaica’s Bad Mind hits. Haunting and haunted, these songs sound like premature requiems, de profundis, coming at us live from the depths. Was hope alive? I hoped so. Hope had to be there, somewhere, as ultimately, humans cannot live without it.

*

The producer most responsible for the Bad Mind sound, I’d heard, hailed not from Kingston but rather a volatile area outside Montego Bay called Salt Spring, on the other end of the island. Born Andre Whitaker, he was better known as Squash. Regarded as charismatic and creative, he posts images to TikTok that highlight his puppy dog eyes, peering from his heavily bleached, tattooed face—the “in” look for “bad boys” in Jamaica—and he poses endearingly with his young children. He also ran a notorious gang, the 6ix, who were as well known for violence as he was for toothsome beats. That was as much as I had to go on.

But digging into the deeper matrix of the Bad Mind sound would prove to be one of the trickiest music stories I’ve ever tried to report.

Squash’s unavailability was easy to understand, as right then he was in jail in Florida on ICE charges. But almost everyone I tried to speak with was wary, I quickly gleaned, about what the Jamaican media have dubbed the Salt Spring Gang Wars: a steady barrage of killings, over recent years, in this and other garrisons also known for music. Salt Spring is Squash territory, just as its next and rival town, Flanker, is known as the stronghold of Tommy “Sparta” Lee. Interviewees displayed a reluctance I had never encountered in six decades of music journalism. They suddenly left the island or stopped returning calls. People didn’t want their names used. Was I living one of my beloved Agatha Christie mysteries?

First to vanish was Rygin King, whose melodic track, “Song Cry,” always reached out and touched from the car radio. Rygin had recorded with foreign rock stars like drummer Zak Starkey and his singer wife, Sshh Liguzz, who put us in touch. And we did speak briefly. Rygin told me of his busy schedule in America, where he’s been living near Miami, still doing concerts while undergoing physical therapy. He confided his interest in writing a book about his experiences; he seemed eager for any help I could give. It seemed worthwhile. He was determined to use his fate as a positive example. But when time came for the interview, Rygin ghosted me—an unusual move for an artist on the make, and one that made me paranoid he was feeling paranoid.

Luckily, a friend of a friend introduced me to a source close to the various communities and investigations key to this story. This crucial guide, who hereinafter shall be known as Nameless, explained to me that the 6ix crew, like most Jamaican gangs, generally liked to keep their wars confined to their own HQ; the Jamaican police and Defense Force are in a valiant struggle to make sure it stays that way, and that the fighting in Salt Spring and nearby doesn’t spill over into the prosperous tourist hub of Montego Bay—even as the 6ix crew has succeeded in spreading its gangsterism to Atlanta and Miami.

The 6ix was a formidable two-headed creature, it seemed. The gang was also a sound, and it was Squash’s “riddims” that had inspired Rebel Sixx. His belief in the 6ix seemed absolute; most of his songs start with a sibilant utterance of the numeral. But before I tried to make my way to Salt Spring—with the guidance of Nameless and Alex at the wheel—I sought out Shane-O in Kingston. Buoyed by banks of harmonies, I had already begun to turn to his music when fending off despair.

Hold On

Bad Mind ghetto dramas were lived material for both Rebel and Shane-O. Rebel’s mordant irony compelled me, while Shane-O’s swelling melodies moved me differently. And Shane-O was accessible. Having grown up in a garrison called Common Pen, at the foot of a steeply climbing hill in Kingston, his success has seen him move to its breezy heights.

In the 1960s, “garrison” emerged as Jamaica’s territorial term for communities built by one or other of its rival political parties, to house residents of slums cleared to construct them. These neo-Stalinist concrete enclaves, replete with violence and absent licit economic sustenance, became fiefdoms controlled by gangsters who do their political patrons’ dirty work, leaving the manicured hands of those who run the system clean. The boat is only rocked when the dons start to think twice about who it is they report to, or look for better deals elsewhere, on or off the island. The notorious Kingston don Christopher “Dudus” Coke, whose father was implicated in the attack on Bob Marley, ran the old JLP garrison of Tivoli Gardens until 2010. His extradition to an American prison made international news and embarrassed Jamaican authorities; not only did Coke and his Shower Posse enjoy the support of the country’s people, but it was revealed that Coke had links, through legitimate businesses he owned, to the Jamaican government. As much as a garrison can be an armed fortress, it can also be a culture, community, and home, as Shane-O told me of the one where he grew up.

An engaging character with shrewd yet merry eyes, the singer of “Hold On” has a jaunty uni-plait hairdo and an affinity for cartoon graphics t-shirts. Shane-O’s lighthearted affect, as we spoke, countered the emotional intensity of his videos, in which he’s seen listening carefully to his grandmother’s advice; wailing his Bad Mind choruses, a solitary anti-hero ranting on a pier against a turbulent sea; or dropping to his knees, frenzied, in the middle of a busy highway.

Common Pen, he tells me, “is an educated garrison. That means they teach you how to move, when to talk, when to see, hear, or act deaf. Principles. Common sense. We keep party’ and no one dead round there. I am proud to hold the vibes, play with the musicians. When I am there, it is all – Shane-O!” He mimes the happy fans and smiles. “Yeah, it is my garrison.”

That feeling may enliven Common Pen, but not all garrisons. “You cannot be careless,” he tells me of visiting rival areas, and I should look out for men with guns. “It is not a joke. As an artist you are not supposed to go certain places. If the police don’t understand and start to say you are involved with guns, start to brand you as a don, then you are a target. You have to be aware. It is a skill.”

For Shane-O, those skills were absorbed early on. Raised in poverty by his mother, who often didn’t have food or water for her kids, he credits his mostly-absent father—a skilled singer and DJ in Common Pen—for his musical talent. His lifeline was an older youth called Sno-Cone, who would help him out if he had nowhere to eat or sleep, and took him in the studio to record his first single, “Rice and Peas,” aged 11. Big artists like Beenie Man and Bounty Killer were there, but Shane-O wasn’t nervous. “Mi haffi do what me haffi do.” The record did well and he went on to perform, that same year, at Sting, an annual showcase for dancehall’s latest and greatest.

In this villa that he rarely leaves except for shows, he plans to install a recording studio. It feels like a communal “ranch,” with sundry dread bredren making it their HQ. He coos over the white pigeons who take pride of place in his backyard. And then he shows me to his ample villa’s cave-like basement. It’s a utilitarian room I recognize from his video for “Dark Room,” a fraught, luscious song that’s among my favorites.

It feels like a privilege to sit right next to Shane-O on the low, velveteen ottoman he’d used in the video . He launches into a full-throated acapella performance of “Hold On,” which always cheers me with its message of tenacity for hope. “It’s for the people who have it hard,” he says, before he segues into “Distress Of Mind,” from his forthcoming first album: “Where is the end of the tunnel, can someone show me / Mi wanna bawl Jah Jah / Help me out, tek me, hold me / Place dark, can’t even read a story.”

As Alex and I listen, entranced, he sounds out the chorus, then explains, “When the lights turn out, it is murder, official, a whole heap of bloodshed. That’s the place where we ghetto youth grow up. I always sing ‘dem kind of music, to hold on tough to life, as long as life lasts.”

Why do so many of his songs revolve around Bad Mind? Shane-O snorts with appreciative laughter at the analysis, then gets serious. “It’s people [who] try to fight and hold down other people, when they don’t even know a person. Nuff people me’ a meet, and me no’ know what a gwan, but it becomes a strong fight, bad mind – active! When you’ talented, it terrible.”

I ask if he knows much about Rebel Sixx. No luck, though he appreciates his music and knows of his fate. He shakes his head. “I live like this, often in a room by myself,” he says. “So me just live, because on earth, you have to work with it while it goes by.”

It felt like he was echoing Marley telling me in 1976, “Me is not a man who move up and down too much.” Days later, gunmen had assailed his house with fatal intent.

As we’re leaving Shane-O’s yard, I wonder if there might be another Peace Concert, like Marley had? “It no gonna work,” he replied. “The government alone can do it, but they themselves have their own wickedness them must deal with.” But hope is a must, Shane-O insists. “If it used to be nice before, it shall be nice again. The bass and the one drop soon come back,” he says. “So it go.”

Heartily encouraged by our session, I mention to Shane-O, before his wrought-iron gates close behind us, that Alex and I plan to visit Salt Spring. His face grows somber. “Salt Spring is rough,” he warns. “Remember, dem have a curfew.”

Salt Spring

Survival is serious business for prominent artists like Shane-O. On a recent episode of a popular online show devoted to Caribbean music, “The Fix,” the host asked singer Jahlanno, a friend of Rebel Sixx, how he “maintains neutrality.” Dapper and astute, Jahlanno had his reply ready: “I don’t try to be the best. It comes with a lot of things. Once you get to the top, you still have to keep climbing and don’t fall. I just try to do my thing, the way I do it.”

What a signal to send for survival. But also canny advice, it was clear, on this island where the epicenter of the bass-less Bad Mind sound appeared to be one of its most notorious garrisons: Squash’s home area of Salt Spring, a few hours’ drive from Kingston and reachable via a turn-off from the highway that lines the island’s beautiful north coast, leading to Montego Bay.

Obviously, this was touchy territory, but surely with the help of a local, we could enjoy a moment in some local hostelry? Alex asked an Old School Friend who lived there to accompany us, and he agreed, so off we confidently set to meet him in Salt Spring.

The drive along the North Coast in the parish of St. James curves through a series of mellow bends beside the turquoise ocean, or what you can see of it between high mansion walls. This is the Caribbean’s true Gold Coast, a series of towns whose Spanish or English names—Ocho Rios, Gibraltar, Salem, Rio Grande—remind us of all the blood shed here in the serial conquests of invaders from Europe. The Taino or Arawak Indians, Jamaica’s first nations, were genocided within fifty years of the Spanish arrival, followed by 400 years of subjugation under varying levels of sadistic brutality or social suppression under the British. By the side of the road, old water wheels that kept the plantations turning are now historical landmarks. Fantastic examples of workmanship and engineering, they are a testament to the skills of enslaved people, and still so valued that they have not—as one might think—been torn down stone by stone.

After independence, and a collapse of the global market for the one natural resource—bauxite—in which Jamaica is rich, the island’s leaders decreed that tourism was to be the key to financial independence. Shifts in the weather and the world economy alike can torpedo income from tourism. Within the hotel industry that dominates the North Coast, there are opportunities for jobs, but often no pay for workers in the off-season. There are energetic Jamaican-owned resorts like Sandals and Couples, and characterful boutique hotels like GoldenEye and Jake’s, but most of the money earned by big resorts owned by American or Spanish conglomerates leaves the island. The stubborn colonial mentality that shapes much of the tourist trade is also reflected in the fact that Jamaica’s residents don’t have access to many of their own beaches, carved up as they are between billionaires, foreign governments, and hospitality chains. And an island dependent on tourism as its main “industry” is vulnerable, like an aging courtesan dependent on fading charms.

But I’m reminded as we drive the North Coast that at least Jamaica’s beauty is eternally ravishing. Tourists are needed, and there is plenty of reason for them to come; the ghetto incidents depicted here won’t touch them. In Ocho Rios, we pass a mural of the North Coast’s musical godfather in the 1970s, Jack Ruby, bumping fists with his bred’ren, Bob Marley, born nearby in the “garden parish” of St. Ann. As we pass towering cruise ships, Dunn’s River Falls, the Dolphinarium, and enter St. James, nearing Montego Bay, I recall what Nameless said about the workings of the underworld in this parish. Known as an epicenter for credit card fraud and other financial scams, the parish’s local Jamaican perpetrators, targeting marks around the world, have become infamous. “St. James’ persons whose wealth comes from areas other than music,” he told me, “use music to legitimize someone with potential. Scammers and people who do fraud will back this person as their producer or manager, laundering their money. Almost all the gangs in St. James are connected to a musical person.”

Salt Spring, I understand, is a JLP area run by Squash. The nearby garrison of Flanker, Nameless has told me, is affiliated with the rival PNP. Both areas have recently been ravaged by murders aggravated by splits among the gang factions. Gangs don’t only have friction with those they attempt to dominate; they have intra-cell beefs that cause them, like amoebas, to continuously divide.

Gang-associated musicians, whichever team they bat for, often release celebratory tunes describing local murders with grim detail only insiders would know. Gangs lure young artists by giving them access to popular “riddims” to sing over—with the ever-lurking danger they’ll get in so deep they can’t back out. While St. Jams has always had an underground economy. “The trade kept on re-defining itself,” Nameless told me. “Before it moved to cocaine, back in the day when marijuana was illegal, the Rose Hall stretch of straight road would be closed for 5-10 minutes, a plane would land, load up with ganja, take off, and the traffic would move again.”

His words echoed in my ears as we drove down that very same scenic strip, past the lush green lawns of the Rose Hall Golf Course, some miles outside of Montego Bay proper—and then Alex’s phone rang. It was the Old School Friend. Something had come up. Despite our 3-hour drive, he couldn’t meet us after all. Nevertheless, we had to try and get at least some sense of what Salt Spring looked and felt like. Its energy propelled the dance sounds that turned so many of its youth into “soldiers” of various kinds—some combat-ready—but many conscripted into armies they never wanted to join. Three miles before the turn-off for Salt Spring, we took the road heading to Flanker—its rival garrison and the home of Tommy “Sparta” Lee—instead.

*

Salt Spring, like much of coastal Jamaica, was a plantation in slavery days when the phrase Bad Mind was born of the horrors its residents endured. In 1774, the sugar plantation at Salt Spring belonged to one Joseph Bowen, and produced 93 hogsheads of sugar; it was the enforced home of 151 enslaved individuals as well as 4 men bearing arms and 8 “women or children.” The human trade, of course, is the Great Crime, bigger than scamming—the primal scar that, along with the death of the Tainos, wounds Jamaica and with it, the world. It’s perhaps only fitting that this island, once known as the “Reaper’s Garden” for its brutality, is now also where Tommy “Sparta” Lee invented what’s known as Gothic Dancehall.

Since his recent release from a two year stint in prison on gun charges, I learn Lee has been laying low: even his own co-workers can’t track him down. With his music’s allusions to horror films and devils, the leader of the “Sparta Army” is a divisive figure in Jamaica, despite his huge following. On this island full of churches, he invited accusations of satanism by releasing the song “Daddy Demon,” and adopting the title as his alias. Then there’s his track, “Psycho,” familiar to players of Grand Theft Auto 5, for whose video he donned a slasher flick mask. It seemed unlikely that we would get to talk to Tommy Lee, but some miracle might make it happen.

We drove up the road toward Flanker until we encountered signs of life; a bar with a tree-filled, shady garden on the right and what looked like a lumber yard on the left. Behind this comparatively prosperous outskirt, I knew, there sat a shanty town––fetid, oppressive tenement alleyways and tumbledown shacks strapped together with flotsam of the garbage heap, zinc if you’re lucky. But around us, Flanker seemed to be booming.

A curious feeling came over me as I took in my immediate community of low concrete bungalows and its busy flurry of building work, with second stories and balconies being added on. A couple of years ago I was a victim of the global scamming web whose HQ, both Nameless and the papers said, was located right here in Flanker and in its nearby, though apparently hated neighbor, Salt Spring.

While trying to receive some funds in 2022 to do building work, I was fiscally fileted by a smooth-talking Jamaican man from Mandeville who operates in America, supposedly specializing in insurance and real estate, but actually majoring in scamming. (His name starts with alphabet letters that follow one another – contact me if in doubt.) An innocent, I walked into his trap. As I write, I am still painfully trying to crawl back into the Western banking system, and it ain’t easy. The stress takes a toll. I had to deal with the domino effect of sequential bank accounts suddenly folding, taking my money with them for months because of the fraud. My scammer cost me, in addition to money, many months of positive production and my fiscal standing. Scammers and hackers are vampires who suck money and identities like blood. According to Nameless, some of them are very gifted individuals, performing more than one role in a single phone call, hoodwinking poor twits to part with their pension. “If these guys would put their minds to doing lawful things,” as Nameless sighed, “the sky’s the limit.”

My fraud hell gave me a more intimate feeling of connection to the flurry of new construction I could see in Flanker––maybe in my own small way, I had helped fund those fake Doric pillars stuck in front of little bungalows for a sad go at grandeur. And as if determined to contradict the area’s bad rep, locals in the inviting yard of the small but colorful bar gave me a major welcome. I was invited to sit, play dominoes, have a beer. Then I mentioned our mission to visit Salt Spring. Oh, dear. Heads were shaking and frowns all round. “You’ll never get in there,” said a domino player, just as Alex called me over from across the street. By the lumber yard there, a group of guys included a friendly man in neat jeans who insisted: “Forget going to Salt Spring. You won’t be allowed in.”

Our new friend, it turned out, was a cop who informed us we’d just missed Lee himself. The compact car we’d seen pull out of the lumber yard just as we’d entered contained the man we sought. Perhaps he’d been warned, by some angels or devils, of the media’s impending approach, though we hadn’t known it ourselves. But with darkness soon setting in, our luck turned.

The cop was moonlighting as a bodyguard and introduced us to his client, who explained, “Tommy Lee is my uncle. I am an artist also. My name is Diedohh.” A quizzical, heavily tattooed fellow wearing a sleeveless “wifebeater,” he agreed to pose for pictures by the roadside sign welcoming visitors to Flanker. Smoothly, he dropped into a series of poses, some echoing the crouching trigger move made famous by Jimmy Cliff in The Harder They Come, before explaining how his uncle—everyone else’s Daddy Demon—had fostered his rise.

Haunting and haunted, these songs sound like premature requiems, de profundis, coming at us live from the depths.

It was Sparta, Diedohh said, who’d brought him along to sound systems and into the studio, encouraging him to record his first song. In the video for “True Believer,” the personable Diedohh celebrates the chorus, “Live life!” in a neon-lit shopping mall parking lot at night, and then at a wildly orgiastic house party. The video’s effective yet somehow circumscribed urban landscape feels indicative of the physical narrowness thrust upon the inhabitants of these famously outlaw communities, regularly listed as places to avoid, which nonetheless keep churning out fresh music, some but not all celebrating the badness that feeds it.

*

Tommy Lee’s Gothic Dancehall is designed to send chills that are both a reflection of, and a diversion from, IRL violence. For good or ill, Diedohh demystifies his uncle’s demonic presence. “It’s an image he created, not that personal.” Despite all the hissing and scary gesturing, Tommy Lee seems to prefer a quiet life. He had changed his name to Sparta, and built his Sparta Army, as a declaration of independence from former associates like Vybz Kartel—the iconic dancehall artist with a genuinely demonic image, who’s still releasing fantastic music from the prison cell where he landed after a charred body was found in his yard. Vybz hails from a section of the Kingston-adjacent city of Portmore that’s known as Gaza City.

I mentioned the coincidence of the original Gaza Strip, now devastated by war, being in the news; Gaza’s image of beleaguered volatility is what inspired Jamaican ghetto-dwellers to adopt the name. Diedohh hasn’t heard about it. “As Jamaicans, we are locked off from knowledge of those things, though I have a little taste.” As a professor, I suggest he look it up online. One North Coast neighbor reckoned it was natural that a far-off war shouldn’t engage his interest when Jamaica, and this corner of it, is so riddled with domestic ones. But Diedohh is also insistent that, despite the regular shootings and his grandmother’s warnings not to play with kids from Salt Spring, Flanker and its neighboring garrison aren’t at war. “Every community have a little bad side to it,” he says. “Flanker and Salt Spring [people] both have bad intentions. We have bullies in common, but we also have good people.” What most perturbs him these days is the public curfew that’s been instituted in both Salt Spring and Flanker, to try and curtail shoot-outs at night.

“It affects us as young people,” he explains, frustrated. “And it really drains our energy as artists. Often when we reach the show, we find police lock it off.” But this 21-year old, proud that his music is streamed in both Flanker and Salt Spring—and, he says, “in all 14 parishes”—is also hopeful that music can bring peace. “Music is life and music can make a difference,” he says. “I hope that my music is a message of positivity.” He also hopes, he says, to one day work with Squash in Salt Spring. “He’s a friend of my uncle.”

This is surprising, but perhaps it shouldn’t be. Hadn’t deadly political enemies Claudie Massop and Bucky Marshall brokered Marley’s Peace Concert back in the day? With island gossip and the music industry both invested in their rivalries, it may be too complex for Squash and Sparta—even if they privately enjoy each other’s company—to officially hang out.

Nameless has explained to me that Squash’s own backstory and involvement in crime were both shaped by his elder brother—a kingpin of scamming here, who was killed by police before Squash took over his 6ix gang. A divisive and complex figure, Squash has been cleared of scamming charges here, but tainted by incidents like a recent double murder committed by a producer from his crew that was caught on video. He has told journalists that police harassment drove him to move to Florida for a while; others claim the attacks were from his reputation as a “violence producer” of “murder music” and the scammers who seem to surround him as they did his late big brother. Either way, with Squash unreachable in prison I turned to one of his associates, the producer Dindin of Hemton Music, to try and untangle the story of what befell the great Rebel Sixx.

“But it really isn’t me you should ask,” he insisted. If I really wanted to understand Rebel Sixx, Dindin told me, I needed to direct my queries to another island.

Trinibad

Trinidad and Jamaica are both Caribbean islands colonized by the British, but in key ways that’s where the resemblance ends. Jamaica is bigger; Trinidad richer. Jamaica is mostly Black; Trinidad’s population pie is split three pretty equal ways: Black, Indian, and Everybody Else. Trinidad’s economy, like that of its sibling island Tobago (the nation-state of Trinidad and Tobago is known as “T&T”) was long shaped by the unpaid labor of captive Africans, and also by indentured workers from India. But T&T’s modern fate has been carved by geology. Once attached to Venezuela––and still attached, in terms of being an entrepot for its cocaine and guns and human trafficking—Trinidad has oil resources that mean it has long been awash with petro-dollars, depending on the market. Trinis, on average, earn about three times as much as Jamaicans.

Musically, satire has dominated sequential genres of witty calypso, happy, hearty soca, and Trini rap, known as rapso. Starting in the 1940s, Trini calypso was so big worldwide that people thought Lord Invader’s “Rum and Coca Cola” was actually by the crystal-voiced blonde Andrews Sisters – though their international cover hit was rarely understood as referring to local sex workers on the US Navy base built there during the war.

The famous steel pan chimes the sound of rebellion. In this place where drums were once banned by the British, the “pan” was forged in the 1940s from oil cans in the still turbulent Laventille area of Port of Spain. In the 1980s, soca star David Rudder scored a conscious hit with “The Hammer.” Since then, Trinidad has become a much more violent place—along with everywhere else. In pace with “urban” American music, in the 1990s Trinidad’s response to hip-hop was rapso; today’s exponents of the “Trinibad” sound project themselves as musical gangsters reflecting Jamaican dancehall through the prism of Trini creativity.

Above all, on this island that’s been shaped by Catholic culture since colonial days, the sexy glitter of carnival—marking a “farewell to the flesh” before the onset of Lent—is the cultural hub. Climaxes of carnival, like the Soca Monarch Competition, consume the island and magnetize international Trinis to do whatever it takes to get home. Carnival has also long been the main focus and inspiration for Trinidad’s music. But in recent years, as crime and anxiety have come to dominate the island’s culture, that’s changed. On this island where “liming,” an active form of chilling, is a national pastime, party and events promotion are key activities for many gangs. So are sex trafficking, money-laundering, and sand-blasting for concrete used for endlessly ongoing construction projects, many of them born of crime that’s organized, disorganized, or governmental.

By contrast, in Jamaica, and especially on its north coast where Squash is based, the beleaguered economy is based on tourism, and the scamming which, paying for much of the country’s musical output, has itself become an art form requiring ingenuity, teamwork, guile, and expert acting skills. In fatter Trinidad, many prominent gangsters and gangs double as “community leaders” who kill to secure government contracts in areas like St. James, the part of Port of Spain where Rebel Sixx grew up.

*

A wry intelligence in his voice first drew me in. The way Rebel Sixx sang it, bloody images became a sad seduction, leading to contemplation; his sweet and sour sound poetically, cynically, recounting brutality with a honeyed soprano and heavenly timing.

He was a musical original, and I had no idea when I first heard his music that he was dead, let alone the circumstances. When I fell for Rebel like any fangirl, I assumed he was Jamaican as he was so popular there. During that year I spent back on the island, his songs were everywhere—the bleak delicacy of his and Travis World’s “No Trust No Love,” and “Rifle War,” “Ghetto Prophet,” “Message to the Heart.” As I adjusted to the feel of this music, oddly bass-free and with an alarming emphasis on the evils of Bad Mind, realizing my favorites were by one artist helped me to absorb and understand the new sound.

Among the phrases Rebel spread was “Fully Dunce,” a backhanded compliment. When the expression wound up on bookbags and t-shirts, Rebel was accused of spreading anti-intellectualism—whereas he was always encouraging youth to keep studying. His sardonic throwaway had been enough to start a craze and a controversy. His early death disturbed me so deeply, I needed to find out what had happened.

It was, I soon learned, a direct hit. Two masked men broke in at 11:45 PM on Sunday, July 5, 2020, and shot him 20 times at close range at his home in Bon Air Gardens, Arouca, outside Port of Spain; Rebel hadn’t heard them enter as he was on his Playstation with headphones. Obviously Rebel had upset some people badly – but his music sang so implicitly of humanity with all our foibles! Why would people want Rebel killed, even as his art was deepening?

Having been at Bob Marley’s side in London and Kingston, in those months and years surrounding the dons’ attempt on his life in 1976—and having seen many friends and associates killed after the Peace Concert there two years later—Rebel’s murder hit me with a sort of contact PTSD. It seemed, whatever the details, a part of the same sick phenomenon. Bad Mind. A targeting of the most gifted artists that also seemed to share hallmarks—politically motivated gang allegiances—with Bob’s narrow escape. I was haunted by Rebel Sixx’s murder.

Laconically, he loped through his videos of bullets and betrayal with self-effacing detachment, as if to say: look at the craziness we have let ourselves get into. Along with the music, it was the philosophical sorrow in Rebel’s eyes that compelled me to explore his story. Whether in interviews or music videos, even when surrounded by a dancing, drinking crowd, his eyes signaled that he was running—making music—as fast as he could, trying to keep ahead of the doom he could sense was chasing him down.

But whichever hellhound Rebel tried to out-run had caught up with him. His friendship with Squash, the 6ix boss from Salt Spring, was the link between the Jamaican scene I was familiar with and Rebel’s Trini milieu. But Squash was unavailable. Not only was he incarcerated in Florida on ICE charges, but Salt Spring, his HQ, was impenetrable under police lockdown. Dindin, an associate, turned my quest around by directing me to the other island. “Find the one who knew Rebel best,” he said. “His producer in Port of Spain: El Faltino.”

*

Seen over Zoom sitting in the shade of a white-walled building, El Faltino, aka Asim El-Salih Faltine, was a humorous, quick-witted man with a boho uni-dread. He told me he’d met Rebel in 2019, on the Friday after carnival. "We were on a musical journey together.” Among the claims to fame of El Faltino’s area, Belmont, is being the birthplace of Stokely Carmichael, the 1960s Black Power activist. But the foremost artist it had recently produced when Rebel came on the scene was Faltino’s artist K-Lion. Born Kwinton Thomas, the sparky young man’s light, skipping vocals were pushing a new strand of Trinibad he and Faltino were calling “Zess.” Rebel and K-Lion became friends, and went on to record together. “K-Lion was so young, but very talented, one of the few artists we all looked up to.”

Firmly, El Faltino continued, “Rebel was the young Ghetto Prophet he sang of, speaking his mind in his humorous way,” he says. “But a lot was going on. He may have offended certain people…”

The producer’s worldview, if not cynical, is sophisticated. “In Trinidad each and every one of us have bad friends, even if we not bad,” he explains. “Big businessmen use money to control youths’ heads and those who are too sensible to take a buyout may have a problem. But Rebel had the power of the streets without having to use a gun. He planned to build a school in his area, he was developing other artists. It was a whole movement. Rebel did not deserve it like that. He was always on a good path.”

This didn’t prevent him, though, from falling prey to people who’d helped build him up. “Very small grudges can be turned into big issues,” El Faltino says, “because of power and egos. What happened to Rebel is jealousy, bad mind coming from people who are trying to control the youths’ thinking. Political corruption in high and low places. His murder is bigger than people think.” How exactly that’s so, he doesn’t say. But he does suggest, if I want to know about Rebel’s last days, and what led him to them, that I talk with his last manager, Hugh Callender.

*

“I don’t think of Rebel’s death as martyrdom,” says Hugh, a garrulous, eloquent man whose bushy beard fills my phone’s screen when we connect. “He was on a pilgrim’s journey—and his journey was a big one.” Rebel was also, in Hugh’s estimation, the foremost exponent of the exported Trinibad sound.

He tells me about how the bass-less sound of Trinibad, and of dancehall in general, reached Jamaica. It’s a story, he says, that begins in the 2010s, when the heyday of dancehall stars like Vybez Kartel and Popcaan—whose hits didn’t want for booming bass lines—began to fade. When it did, around 2016, a Trinidadian producer named Isaac Cozier began experimenting with a sound that joined dancehall beats with soca touches that Cozier laid, crucially, over the bass-less feel of Afrobeats. It was a sound that El-Faltino and others in Trinidad embraced. So did key “riddim”-makers in Jamaica, many of them associated with Squash—among them my contact Dindin and another prolific producer called Automatic who has, Hugh says, spent much time in Trinidad.

The key moment in the transition from Zess to Trinibad, Hugh says, came in 2018. “That’s when it went from party music to life music. From light to dark.” Artists like Swanny and Teacher were key to this shift. “But no one bus’ like Rebel. Like Mount Rushmore, he was the last president—the most influential. With Rebel, Trinibad went from life music to action music. To soldier tales, and stories of war. Stories you only get from living it.”

When Rebel was growing up, Hugh tells me, his mother was an ardent church-goer. She made him join her church’s choir, where his soprano was prized. But it was in church that he earned the nickname Rebel, because he was the one always pulling pranks. Growing up, he became a star school athlete and sang in a harmony trio, Z-Tech. But his upbringing was not smooth. When Rebel was young, his hard-working mother, a nurse, had to travel a lot and lived for periods in the U.K. His father, a singer called El Negro, was not a stable source of guidance or love, and moved to America while Rebel was very young.

On TikTok, there’s a video that would have surprised the youth. It’s of El Negro being applauded in a nightclub—not long after his son’s funeral—for singing Rebel’s “Rifle War,” a much-loved, ironic critique of gun fever. Comments beneath the post indicate that many in Trinidad knew how little El Negro had been around for Rebel.

Before he became Sixx, aligning himself with Squash, Rebel was just called Rebel. And as a youth left to raise himself, he created his own family. In his early teenage years, Rebel and his best friend Swanny harmonized together in a trio they called Z-Tech. Like most youth in their area of Port of Spain, they also became affiliates of a gang called Rasta City. But then Rebel decided to split off. Locals look back nostalgically to that moment just before intra-crew beefs saw Rasta City and their rivals, Muslim City, sub-divide into cliques that sound like numerological codes. Certain “Muslims” became known as “9.” After Rebel began identifying with the 6ix, whose members here nurture mysterious ties to Squash and Salt Spring, Jamaica, Rebel’s old friend Swanny joined with other erstwhile members of Rasta City who started calling themselves “7” and “4”––as if picking the right numbers could be a free pass in the lottery of death. Between Rebel and Swanny, a notorious frenemy-ship was born.

The 6ix were loved and feared. What was their true identity? Squash had a keen instinct for making hit records, with a following for his own songs like “Trending” and “Money Fever.” On TikTok, he posed for pictures with his adorable children. But still, I venture to Hugh, maybe not the sort of the guy you’d bring home to mother? He chuckles. "You'd be surprised. Squash can be so endearing, before you know it, he'd be back again, cooking dinner for your mother!" Yet Squash also posed with heavy weapons on TikTok, in his other job description as the inheritor of his late brother's scamming syndicate, and he’s a face of Jamaica’s larger G-City gang, whose connections with criminal organizations were terrorizing Atlanta and Miami.

But Rebel, by all accounts, didn’t care about this side of his mentor. When it came to Squash, Rebel was a fanboy. And then he was a prize. In Jamaica, Squash heard and loved Rebel’s work, and their online exchange led Squash to visit Trinidad, and Rebel, with members of his entourage.

It was during that visit, Hugh says, that Rebel first turned up to use the recording studio he managed. (With his partner Kyle West, Hugh now runs WeLove Productions, a company that works to develop corporate brands and artists.) Cracking jokes but working hard as ever, Squash turned the session into a productive party. He said Rebel had been invited to join him in his capacity as “the only official 6 in the country,” as Hugh put it. After all, Rebel had adopted the name Sixx from the music’s inspiration alone, before ever meeting the producer who crafted it.

It sounds, I suggest, like being invited to join the Freemasons. Hugh laughs. “It felt almost like that. It was the relationship that they have, and how they keep this circle. You feel very safe with the 6ix, as a creative. Here in Trinidad you kinda have to cross a lot of mountains and rivers to get to where you want to be. But them fellas move with a kind of confidence that makes you feel like, you know, it have no mountains. It have no river. It’s just flat road. Because they have a kind of ‘do anything’ mindset; there’s few limitations between creative and content.”

They maintained contact. Hugh even filmed Rebel at home. Though low-key at first, Rebel was the only one of the many denizens of the studio whom Hugh encouraged, to respond seriously to his support: “I have a plan. I want you to manage my music career and platform and help make this dream real.” Their collaboration began on Christmas Day of that year. “I have never known a musician to work harder than Rebel,” Hugh recollects. He would be in the studio at 8 and leave at 10, and write 2 or 3 new songs a day. He worked even harder than Squash.”

He continues, “Rebel and Squash had a lot in common. They both raised themselves on the streets. The only difference was, Squash is very close to his mother and they were often together in Jamaica. Rebel was also close to his mother, but they could only speak on the phone as she was often working in England. He hadn’t seen her since he was a kid. So it felt good that the 6ix family embraced him fully, he was like their extension in Trinidad. That is the honor they graced him with.”

In a TV interview, Rebel said, “I talk to Squash every day. He is literally like a father to me. Literally. He is my mentor.” If from distant Jamaica Squash became a replacement for El Negro, in Trinidad Hugh—businesslike and a big thinker—and El Faltino—the energetic hipster—became Rebel’s guides to the music business. “I am an elder in the business,” Faltino says. “Rebel used to call me Fada, even though I told him not to!”

Hugh explains it this way: “We were trying to smooth up his image for the public but still keep it authentic. Under his ministrations, the packaging, marketing, and streaming of Rebel saw “Rifle War” soar to Number One on the local Apple charts, and appear on numerous playlists, within four days of its release.

The Ghetto Prophet

The more acclaimed Rebel became, the more rumors and negative noises he heard from certain Bad Minds in his vicinity. Encouraged by success, he moved to Bon Air Gardens, Arouca, a slightly “better” neighborhood that was nearer the studio and his family. St. James, where he had been living, was a close-knit community, with old friends. Still, it would be nice to have a change of scene, and there would be new people nearby, like the area leader “Nye,” who occasionally booked him on shows.

But trouble followed him.

A cop living across the road had turned his security cameras on his new neighbor full-time, which was more unnerving than reassuring. Then, to Rebel’s distress, some of his old Bad Mind acquaintances followed him to the new neighborhood, increasing the artist’s paranoia. For protection, he started to surround himself with five or six “soldiers” in the new yard.

Though barbs had been flung in gossip and song, Swanny and Rebel were still, in the public eye at least, in the same groove—they appeared on the same playlists, and put differences aside when paths crossed. Thus, early in carnival season 2020, Rebel agreed to be featured on a group recording of Trinibad’s key artists, called “Big Badness.” It was requested by the island’s powers-that-be, to promote peace. With COVID looming and unemployment and fear rising, the murder rates in Port of Spain were raging, and peace was definitely needed. Rebel responded to the call for unity affirmatively.

Carnival offered him a further chance to show support. The government of T&T, like that of all Caribbean islands, has long maintained an official interest in promoting its nation’s culture. Trinibad’s key figures were put on official alert that they were to disrupt the venerable Soca Monarch Competition, held on February 17, 2020. It was a contest that represented a tradition of friendly creative rivalry quite different from the vicious shoot-outs depicted by today’s musicians. T&T’s boosters and political establishment were clearly banking on the Trinibad sound to sell internationally, despite or because of its lyrical violence—a changing of the guard from the feel-good soca days of yore, but still meant, so the invitation said, to promote peace.

Backstage TikTok videos show the bros laughing, drinking, and singing together. But while the talk was of peace, the gang warfare kept going; murder, in many areas, became the norm. To pick up a newspaper in Trinidad was to glimpse images, at least once or twice per week, of a body splayed in the street.

*

Right after carnival ended that March, COVID hit the island. Rebel dismissed the “soldiers'' patrolling his yard. It was time to hunker down. But not before Rebel played his first show off the island, in Barbados. He was excited, but still irritated by a problem. When the Trinibad crew played the Soca Monarch Festival in February, they had expected to perform their joint peace tune, “Big Badness.” But the release had been delayed. Before leaving for Barbados, Rebel heard that certain artists had never completed their parts and the record had been shelved indefinitely. It was all the more annoying as Rebel had only done it to take one for the establishment team – which was now dissing him.

As Trinidad went into lockdown, Rebel considered staying in Barbados. It was tempting to duck the tensions of home. But he couldn’t abandon his folks or newborn son – and then there was the music. The melancholy lure of “No Trust No Love,” the first Rebel track to fascinate me, turns out to have been a premeditated strategy on the part of Rebel and Hugh, in tune with the times.

“We in Trinidad had just left a period of peace,” Hugh explains. “There was supposed to be no more bad mind. We made ‘No Trust No Love’ on purpose; our effort to go fully international. I calculated it was a good number one, and so said, so done.” On the morning of Wednesday, June 3, after spending all spring locked down at home, Rebel messaged their group chat: “I want to drop ‘No Trust’ today.”

One week after “No Trust No Love” came out, it was top of the T&T Apple Music chart. But then came the blows. On June 10, Rebel and Hugh learned that K-Lion had died in Miami. He was 26 years old and had seemed in perfect health. “It changed Rebel,” Hugh said. “They said K-Lion had a heart attack playing football, but it was COVID time and there was no autopsy. It seemed suspicious. He broke down in the car when he heard, and from that day forward, it was a totally different Rebel.”

Compounding the loss of K-Lion, just days later Nye—the friendly area leader who was producing a show featuring Rebel—was killed. His fate never made the news. Rebel knew he was trapped. No matter that he was trying, like Marley before him, to stay on good terms with every clique on the island. Whatever move he made would displease someone. By now, the jollity of February’s Soca Monarch Competition had evaporated. At a moment when COVID had the island on lockdown, Rebel’s success soared and the demands on him mounted. He became mistrustful of the whole music/political/industry complex and threw himself into a frenzy of creativity. Within three months, he laid down forty new songs—many of which, Hugh recalls, revolved around Bad Mind.

Then came a phone call, from whom Rebel never revealed: an invitation to join a press conference for peace with artists like Swanny, from his old crew, Rasta City, and Muslim City singers including Toppy Boss. This gathering was one of many responding to what became known as the Morvant Killings—the murder of three men by police in that area of Laventille, on June 27, 2020. Occurring a few weeks after George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, these killings’ impact here was akin to that of Floyd’s in the US. As gunfire held citizens hostage nightly, the murder rate spiked alongside mass protests for justice and peace. (In 2022, almost 10 percent of the island’s murders occurred in Morvant and Laventille, averaging at least one a week.)

This time, Rebel turned them down. He was tired of playing what he saw as a phony peace game, particularly as he had spent the previous months wasting his time trying to fulfill everyone’s expectations. He felt the whole thing was more a cosmetic charade than anything, s. He had been jerked around about “Big Badness.” After the unexpected death of K-Lion and the unacknowledged murder of Nye, he had lost faith in what he now saw as a mere performance of peace. Plus, he was busy. The trajectory of Rebel’s career now had a global thrust that looked set to far outstrip Swanny’s, or any of his other fellow Trinibad artists.

On July 4, the rival Trinibad crews gathered for peace. Among the artists present were baby-faced Prince Swanny from Rasta City, and “Muslims” like Toppy Boss, whose career was based on singing about the sort of beefs—including one with Swanny, who had one with Rebel— that buzzed about on the many online sources for gossip about Trinibad. Also on hand were Medz Boss and Lawless, Magic and Siah Boss, Bravo and Leo King and Leroy. Bold hopes were stated to journalists, and the mood was loving elation. But where was Rebel Sixx? Everyone knew the missing musician was untouchable when it came to sophistication, subtlety, and depth. In the Trinibad jungle, his was the loudest roar.

The next day, he was assassinated.

*

No one was ever convicted of the crime, and the police closed the case after a couple of weeks. But it was impossible for the public not to draw its own conclusions. Fans raged that Prince Swanny had been seen on social media happily drinking as if glad of Rebel’s demise, but he could have been laughing at fond memories. With virtually everyone in the T&T entertainment industry and associated bodies involved, how could anyone not be implicated?

What failed to feature in Trinidad’s articles after Rebel’s death was another factor in his complicated, ambitious life. The response to his new song, the 6ix-oriented “868 King,” with its steel pans, had been so strong that Rebel was ready to make a change. “Though Rebel would always love Squash, we were trying to leave the 6ix, this stigma and the box that people were already trying to put us in, and become international now,” Hugh explains. If there really was love in their bromance, Squash would understand Rebel’s need to distance himself professionally—not personally—drop the Sixx, and just call himself Rebel again.

As if to guarantee that some mystery will always envelop Rebel’s killing, there is a dispute regarding the date of the peace gathering held at George Street. Sources said it happened on Saturday, July 4th, the day before Rebel got shot. Others insist that it took place the previous day, and that the mix-up is a manipulation—misinformation calculated to make people think that Rebel was killed solely because he was not there.

*

Several factions were after Rebel; like a John le Carré novel, it was a case of spin the bottle to see who succeeded first. Rebel had been paranoid as he understood twisted Bad Mind thinking. He knew that some would blame him for the death of his pal Nye, the music-loving area leader. Equally, Rebel’s refusal to co-operate with his successor from a different team might have made a new enemy. Or could a threat come from someone who hated the 6ix, or loved them and heard he might leave? Rebel’s reality was fragmenting as if in a hall of distorting mirrors.

Whichever, on the day the papers reported the peace gathering took place, Rebel had a quiet but productive day at home in Bon Air Gardens. In the afternoon, he had a long phone call with his mother in London. Later in the day, El Faltino dropped by. They spoke of Rebel’s plan to move from Bon Air Gardens as soon as possible. “Certain energies weren’t working any more,” Faltino told me. “We were looking for somewhere we could be safe.”

Did you find anywhere? I asked.

"No."

Rebel was pleased to play El Faltino “Badness Cya Done,” a new track he had just delivered to Automatic Records. Melancholy, rippling with subdued beats, the track turned the “Fully Dunce” phrase he made so popular to “Fully Paranoid.” The lyrics run: “You could win inna music/And still get your life lose.”

“It was a message,” says El Faltino. The 6ix are scarcely mentioned in the song; but at its close, Rebel once again refers to himself by his old persona, Ghetto Prophet.

Cruelly, the world was just opening up for Rebel. “In the week before he was shot, Rebel got his first international bookings, two in New York and one in the UK,” Hugh recalled, as he described making his way to Rebel’s house the night he heard of the shooting, only to be told by police the investigation would take its course. “We got a double fee for one of those as a down payment, and after the fact, the promoter said, I don’t want it back. Keep that money for the family and funeral.”

*

The investigation was closed with comparative speed. Maybe we will never know the truth. For Rebel’s friends, some connection between that peace no-show and his death does not seem self-evident. Poetically, El Faltino pointed out that Rebel had people gunning for him in high and low places—instinctively turning to the phrase from Ephesians that Bob Marley used, in his song “So Much Things to Say,” to describe where wickedness dwells. An optical “peace” mentality is the flip side of that same weighted coin as Bad Mind.

“Every time you see a peace concert, just know that behind it is darkness,” opined Hugh. “For somebody to openly propagandize and want to showcase that form of theater, it means they have an agenda.”

He recalled other events less grounded in the community than Marley’s half a century ago, like the signing of a peace accord between warring gangs in 2005. “In the weeks following, all the guys who signed the Peace dropped, one after the next. When these events do rise authentically, there are bound to be attempts to cut them down from the powers that be. They don’t want positive change that doesn’t benefit the establishment, as they see it. In no time in history has it been different.”

The loss of both K-Lion and his bredren Rebel, so close together, cut the sapling of Trinibad at the roots. Toppy Boss mourned them in a song that was otherwise all bums and guns. But an infinity of mourning can sap energy needed to make change. In the fall of 2023, news emerged of yet another new truce between Rasta City and 6ix. But in a scene so steeped in the nihilism of Bad Mind, is it too late to give proper peace a chance?

“Hope is there!” insists Hugh confidently. “Because Trinibad, like rapso, is the new branch of a legacy that comes from steel pan and calypso. They all represent the decision to go against what is popular or deemed acceptable and choose to carve your own voice and your own way. It is a decision, and when those guys make that decision, they almost always accept the rest. It is an attempt to try and leave the situation they have grown up in and it is do or die. The irony is, if you do, you might die too, but you might get a better life and be able to get a house for your mum.”

No doubt Squash has long since bought a fine residence for his beloved, flamboyant mum, Shelley Anne Millwood. Through his travails, she has become his spokeswoman. As I was driving to the airport to fly home to New York and its own lethal forms of craziness—guns and gangs included—news came on the radio that Millwood had just confirmed Squash’s release from those ICE charges in Florida. Interested parties can only await forthcoming music and events from Salt Spring and the 6ix crew, with hope for a sound, soon, that mellows the violence as conscious bass once did. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast