Tipping Over Into Reverie: Jimmy DeSana

Editor's Note: In 2016, Pioneer Works exhibited a collection of little seen (and little known) photographs by late photographer Jimmy DeSana, titled Remainders. The works were made a few years before he died of AIDS, when he was ravaged by the disease; unlike the elaborate shoots he became known for in the 1970s involving nude models posed surreally in hyper-stylized, domestic environments, these works were smaller, more intimate in scale due to him being too ill to organize complex setups.

To coincide with the exhibition, the editors of Pioneer Works Journal commissioned noted cultural critic, poet, essayist, and man-about-town Wayne Koestenbaum to draft a handful of short stories, each responding to a work in the show. Now gathered into the writer's first book of short fiction recently put out by Semiotext(e), The Cheerful Scapegoat: Fables, Broadcast is reprinting Koestenbaum's stories online for the first time, paired with their respective works.

-David Everitt Howe

THE TERROR OF COMPLICATIONS

Maybe I mean the terroir of complications—a certain flinty vineyard in Chablis, where complicated tastes abound?

At the hospital, I saw the nurse bring the newborn infant into the mother’s room. I had no legitimate function in the room. I wasn’t the father. I wasn’t even a close friend of the mother. I was a reporter from the Times, but which Times?

The mother lifted the baby. To her breast the mother affixed the baby, in a moment of compassion and spite. The baby began to familiarize itself with the offered nipple. The baby was instinctively drawn to the nipple but also tentative in seizing it. The mother herself was just a kid, not willing to take on the dreadful responsibility of feeding this scrap of an infant, this poor excuse for a human being.

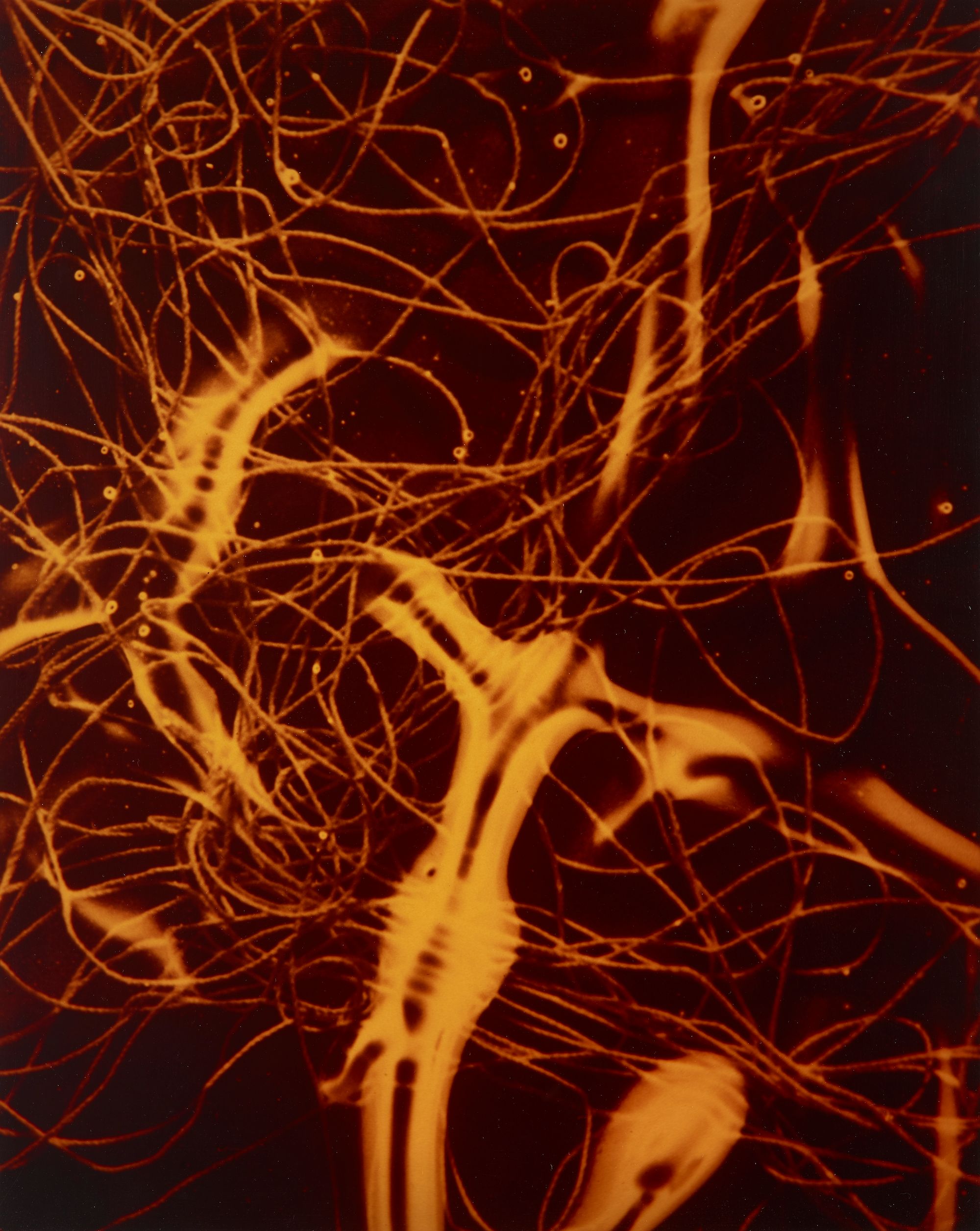

Inside my chest I felt a cough begin to form itself: a small lump of contagion. The lump had threads attached to it, and I was responsible for each of the threads, like telephone wires. The movement of the contagion-lump, in my chest—the lump’s palpitations—resembled an earthquake coming to consciousness, for the first time, of its potential to destroy Crete.

Let me backtrack. The mother’s name was Florence James. The infant’s name was Titian James. Titian had a red birthmark on its neck. Florence, seeing the birthmark, felt cough-like threads form in her heart—swirling tendrils she wanted to extirpate. Florence James decided, “I will refine my consciousness through elaborate yet unseen acts of masochism, and through these refinements I will destroy the spider-web filaments that tie my incipient croup to Titian’s birthmark—the red mark marring the neck of my first-born, a child I plan to disavow after I leave this hospital.”

Florence continued, “The color of the tendrils—connecting my nascent cough to Titian’s birthmark—is ochre, or copper, if copper had been smashed in the head or lightly swatted and thereby turned into a harmless, unlovable iridescence.”

You can see that I feel great responsibility for Florence’s consciousness. You can also probably discern that I feel no empathy for Titian. Titian doesn’t belong to the realm of art. Titian is a mistake. In his capacity as mistake I nominate him for a position on Golgotha. I am a reporter for the Golgotha Times, the newspaper of record for a little-known nation-state, the Kingdom of Needless Suffering.

TELEPHONE RECEIVERS OR COOKING SPOONS IN PURPLE HAZE

“The big lesson I learned from my year of immersion in purple emulsion—a viscous medium used for cloning—was how to quell anxiety in Botticelli admirers, those steely-gazed lemmings who bring their salty provisions in paper sacks to the Uffizi and stand around waiting for analog revelation. It’s better to be lascivious at home, to sit around plucking my eyebrows and applying Anusol to my itchy areas, those cavities sparse in pity and rife with nerve endings. Right? Like a Bauhaus craphole? A Tenderloin technology will soon be invented to recreate homosexual utopias in the desert, like Marfa: new choreographies, new vulgarities. Brian Eno and the Supremes formed a threaded-together “you” and “you,” an après-coup, an afterwardsness I was doomed to reconstruct because I’d forfeited the original fire; the original flame walked by on high heels, an apparition I couldn't drink or transform into vaudeville. What were the words I’d spun? Please don’t you start talking about Botticelli again. An elevated drawing of Fallopian tubes—was that the original flame I’d lost in the desert? Or was it a one-point perspective drawing of Fallopian tubes, seen from Botticelli’s point of view? And was the much-mourned afterwardsness just a sandwich of litterbug potentialities, a swizzle stick Lady Bird Johnson plaint intoned like the terrible Stock Market crash of 1904, when the futures of anyone worth mentioning grew unappetizing as a pizza—a pizza I’m trying to reconstruct (it’s the pizza I call “the original fire”)? On that pizza, small triangles of an unnameable substance were nestled amid the cheese. And I was impatient—impatient as an avocado, the most unsteady fruit, always waiting to ripen, never ripening. And as I wait, avocado-like, to ripen, I try to remember the name of the fruit that preceded me, the fruit I incarnated before I became avocado-like, before the Stock Market crash of 1904. I picked up the telephone in 1904 even though the telephone I picked up was a princess receiver that hadn’t yet been invented. And on that princess phone I heard the message from the desert I’m trying to reconstruct now—a message warning me about pointe shoes, about the torture of trying to fit your your soul’s motility into claustrophobia-inducing forms. Something else I’d tried to communicate to you, in that lost epoch—something about purple itself, its power to make everything a hazard, a toss of the dice… What else did I hide in that secret briefcase now buried under the sands? Had I locked in that briefcase some notes about the remorse plague that spread from mouth to mouth? The remorse I’m trying to describe and remember—it too was a triangle, like the substance nestled into the cheese on the forgotten pizza. The triangle was a small tucked-in object, a proclivity more than a personage. I set sail for that refinement, that edge of a proclivity, on whose shore I would one day land, my boat in tatters. I can’t end this complaint until I remember every detail of what happened in the desert asylum that summer, a drugged confinement I fallaciously bless with the name “afterwardsness” just because that word erupted in the middle of a Supremes tune never sung but held out as a promise of future reward. I could grow a very long beard and put ice in a tall glass and wait for that reward. Or I could return to the memory of that salmon bun I’ve been trying to reconstruct, a bun whose dough was pink and yellow—yellow from polenta, and pink from the flecks of dried salmon the careless cook tossed into the flour. I’m not mocking the salmon bun by mentioning it. I’m begging you to take the salmon bun seriously, and to sing about it to your children. If you ever have children. If the remorse contagion doesn’t strike you down first. How water can flow over the thought of the salmon bun but never destroy the bun and never destroy the thought itself, the thought that holds the salmon bun like a salty potentiality, perishable and not freaked out!”

AND THEN I THREW MY HANDS IN THE AIR

“And then I threw my hands in the air. My camisole had turned yellow, a sea-change. Had the gas begun to penetrate my lungs and blood vessels? Was my incompetence in the process of being discovered by the nation’s surveillance system? That’s a good one, I chuckled. My face essentially folded in half, in a hospitality basement—that is, in the basement of a hotel famed for forgetfulness. The maenad in me—I called the maenad ‘John Donne’—had become the equivalent of Freud’s ‘secondary process,’ and as a result I was lying in a meadow of heather, my face buried nonstop (like Cassandra’s) in the cat-gut strings of the blooms, which make me laugh and sneeze and whistle and issue directives, totalitarian dictations. To coincide with a phenomenon, rather than to glimpse it from outside! I haven’t spoken to them in three hours—the surveillance committee in the hospitality basement—and I must complete my time-sheet soon. I’ve acquired a festering disease, lying here in field of heather… Radical indecision, unvisualizable and finite: am I on a blooming meadow, or am I in a basement? Am I the star of a remake of Woman in the Dunes? Am I the director of the remake, a jazzed-up and goldenrod version of the afterwardsness original, an original film obsessed with afterwardsness, après-coup, like what they talk about at MIT? Everything’s wonderful in the hospitality basement, where I’m hired to sweep and curry favor with traveling idiots. Basically I’m under linden trees, a contrarian under the lindens. That’s final.”

GREEN ICE CREAM MAN I DIDN'T LOVE

The man was green, but the ice cream he sold, from his corner truck, wasn’t green. He didn’t carry pistachio or mint.

The ice cream man I didn’t love seemed to be floating in green ether—or seemed to have been born from a green womb. The womb’s greenness clung to him for the rest of his life. His penis was particularly green, he told me, when we hugged, behind his ice cream truck. The ice cream man I didn’t love was always eager to hug me, because, he said, “You look like a movie star.” In fact, I don’t look like a movie star. Pasty, scrawny, I have a large scar on my forehead.

I touched the butt of the ice cream man I didn’t love. I touched his butt during one of our protracted hugs, behind his ice cream truck. His butt, lazy, harbored no remorse. Nor should a mere pair of buttocks harbor remorse. Why is it the business of buttocks to huddle down with the emotions? Why must turbid anxieties disturb the calm of buttocks whose only ambition is to remain affixed to the legs and hips and torso of a person trying to make a living?

My sadism and remorselessness—almost equal to the remorselessness of Edgardo’s buttocks—will eventually doom me to become as green as Edgardo. Only in the last paragraph of this little narrative have I chosen to reveal the protagonist’s name. I waited to tell you his name because I am afraid that Edgardo’s family will read this tale and sue me for revealing sordid details about their green paterfamilias. We are grateful that no one will ever read this tale, and that no one will contact Edgardo’s family. We are grateful to be invisible, not yet green, though eventually Edgardo’s greenness will become my own. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast