The Jacket

MARCH 11, 2016: Hillary Clinton apologized today, saying she “misspoke” in an interview on MSNBC. The former Secretary of State had stated that Nancy Reagan, who died on Sunday, March 6, and her husband, president Ronald Reagan, “started a national conversation” on AIDS that “penetrated the public conscience.” But the former president didn’t deliver a major speech on the epidemic until 1987, six years after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) first reported on the disease, and after more than 47,993 people had already died in the US of AIDS.

After Clinton “misspoke,” I kept thinking about an odd (in hindsight) episode from Nancy Reagan’s real history: her cover-story in the December 1981 issue of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. Editor Bob Colacello and his assistant Doria Reagan (Ron Jr.’s new wife) had arranged the chat, the first lady’s debut in-depth conversation after occupying the White House. Warhol reluctantly agreed to go down to Washington to conduct the discussion. The same issue featured erotic pictures of men by Herbert List, George Platt Lynes, and even Edward Steichen, who once took an interest in two bare-chested sailors. There were also photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, staff photographer for the magazine, of various glamorous people partying around New York.

It’s strange to think that Nancy Reagan could have been an ally for queer communities, that perhaps the homophobic culture wars of the 1980s could have been avoided. Was this what Clinton imagined? Probably not. Right after her statement was published, a fierce outcry broke out across social media. Many people were particularly enraged that the truth surrounding the Reagans and AIDS—the administration notoriously saw the disease as only afflicting gay men and, to a lesser extent, intravenous drug users—continued to be forgotten, ignored, and, even worse, fabricated. The redrafting of the past had to stop.

Clinton wasn’t the only presidential candidate putting out fires that day. Donald Trump’s campaign cancelled his Chicago rally moments before it was to begin, citing security concerns. Hundreds of anti-Trump protestors had breached the rally’s University of Illinois venue, and police arrested five people as violent clashes broke out. Trump called for “peace” in a statement, and, while I wasn’t sure what was going on with Clinton’s bizarre misremembering, Trump’s words amounted to a withering sarcasm.

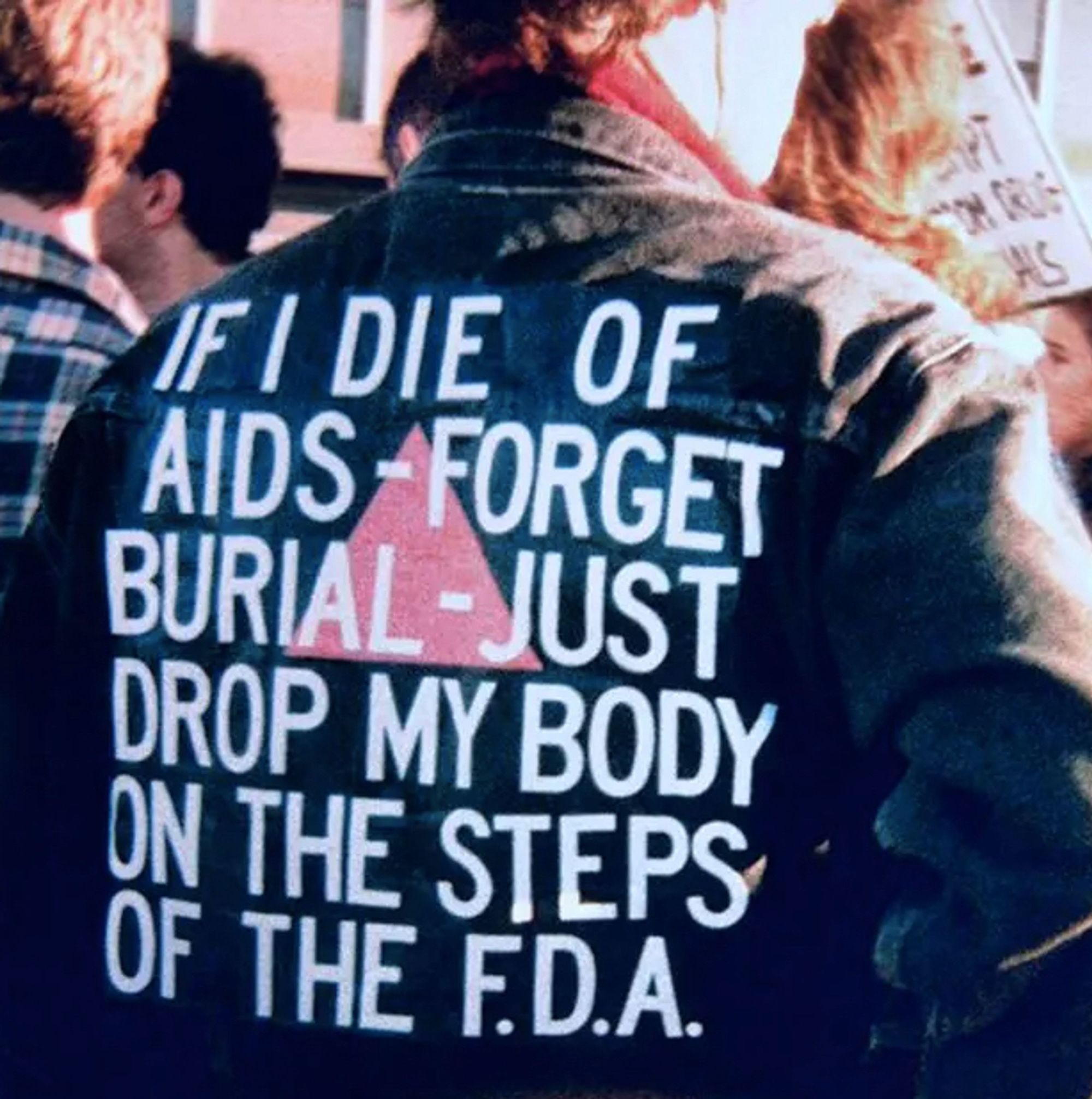

Meanwhile, an iconic image of the artist David Wojnarowicz began to circulate on Instagram, from a protest that took place in another, not too far away world. It pictured him from the back, wearing a bespoke denim jacket during a 1988 demonstration at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) headquarters. The image was taken by activist and lawyer William Dobbs. Over a painted pink triangle (a reclaimed LGBTQ symbol, made in response to the upside-down version used by the Nazis) Wojnarowicz meticulously scripted a rageful text in white letters on his jacket:

IF I DIE OF AIDS—FORGET BURIAL—JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA.

In 1988, Wojnarowicz was 34 years old. He had been diagnosed with HIV the year before and he was known for his deep sense of parrhesia: an obligation to speak out, even at personal risk. The Ancient Greek tragedian Euripides, who coined the term, would have loved Wojnarowicz’s capacity for refusing silencing and the production of false histories. (Tragic theater, particularly its tradition of showing violent wounds, and activism are uniquely interlinked. The tragic plays were one of the earliest forms of activism, but that’s a story for another time.) In 1987, after the death of Peter Hujar, his longtime friend/mentor/lover, Wojnarowicz became more politically active, crafting works about AIDS and the political conflicts in El Salvador. Prior to this, one of his main outlets for expressing his political views was his East Village band 3 Teens Kill 4, which he was primarily involved with from 1980–83.

Wojnarowicz’s parrhesia found a home in his bespoke jacket. He knew that it helps to come up with a short and iconic statement, something that follows the logic of activist art—take, copy, distribute—which is a trio that prefigures the self-propagating digital meme while also contributing to the legacy of the multiple (a series or edition of identical artworks). Some were already incubating statements, namely the 1987 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) project for Silence=Death and General Idea’s Imagevirus, 1987–1994.2 Wojnarowicz may have had those in mind when he wrote the text; it’s also possible he was crafting his 1989 catalogue essay for Nan Goldin’s “Witnesses” exhibition, “Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell,” in which he wrote:

"I imagine what it would be like if friends had a demonstration each time a lover or friend or stranger died of AIDS. I imagine what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers, or neighbors would take their dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles to Washington, DC, and blast through the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and then dump their lifeless forms on the front steps. It would be comforting to see those friends, neighbors, lovers and strangers mark time and place and history in such a public way."

Vulnerability, abandonment, and communal decline had become central to his art, as evident in his stark and somber untitled photograph of buffalos falling over a cliff, which U2 famously employed as an album cover for their single One. Wojnarowicz took the picture at the Natural History Museum in Washington, DC, in a diorama showing the mighty bison being hunted. The image still circulates widely on social media, but the picture of him in the jacket has been gaining traction since at least 2016 and may have eclipsed it. What’s more, its text has turned into its own image “virus” and has mutated, as variations on a meme. Adopted by different people in different cataclysmic circumstances, the transmuted text in each case has condemned a government that didn’t operate under conditions of maximum public transparency, nor communicate the real scope of a threat to endangered populations, nor implement measures of mass testing and preventive care. In the face of a public health emergency and a rising death toll, the people circulated their own infection.

William Burroughs’s idea of language as a virus from outer space—of humanity as infected by a language-virus that is really a medium for social control—is relevant here as a foil, though I don’t purport to totally understand what he meant by it, and likely he didn’t want it to be understood, anyway. But it helps to show the flipside of this story, of this coin: That take, copy, and distribute is a tactic embraced by most political campaigns. This is an ancient and non-partisan strategy: meme (a word modeled on gene), which derives from mimeme (or the Ancient Greek μίμημα): an imitated thing.

Another word derived from Ancient Greek: metaphor. The original Greek is μεταφορά (metaphorá), or “transfer.” Today in Greece you can still see the word emblazoned on certain trucks and vans carrying boxes and furniture, as the modern Greek equivalent, metaphores, means “movers,” or those that transfer stuff from one place to another. Metaphors and illnesses often function as bedfellows, which is something we should always be wary of, per Susan Sontag. “My point is that illness is not a metaphor,” she wrote in 1978, “and that the most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”

In a series of three essays first published in the New York Review of Books (and collected six months later as the book Illness as Metaphor), Sontag famously tracked the influence of metaphors linked to diseases such as tuberculosis and cancer, and how these comparisons were applied to ill people so persistently that they obscured the actual facts of the illnesses. (For example, it was said at the turn of the last century that people contracted tuberculosis due to “too much passion.” Fifty years later, cancer stemmed from “psychological repression” and “insufficient passion.”) In 1989, Sontag applied her same ethical analysis in a follow-up book, AIDS and Its Metaphors. Throughout the 1980s, the Reagan administration and the conservative Christian right held that those with HIV contracted it because they were prone to “moral laxity or turpitude.” Some even believed the disease was a divine punishment, and so, as Sontag writes, “With this illness,” as with others, “the effort to detach it from loaded meanings and misleading metaphors seems particularly liberating, even consoling.”

Wojnarowicz’s “If I Die…” statement is resistant to metaphoric thinking, and almost comes off as a response to Sontag’s book, which is why I bring her up (though, I always want to bring her up). The subsequent variations on his jacket are also not metaphors. They are not clicktivism. They do not delay nor thwart the treatment of a problem or disease—rather they are urgent calls for change. I want to be clear on this because I’m afraid that in the endlessly context-less context of the internet, these images may seem as such.

Under the sign of Sontag (and Wojnarowicz), my intention here is to push back against the idea that diseases, illnesses, and pandemics are political metaphors because, more often than not, such representations are only used to further marginalize and target underprivileged and vulnerable communities. As I write this, I fear that the constant metaphorization of the novel coronavirus will enable new surveillance technologies beyond contact tracing. I worry that the creation of metaphors is a way of distancing, forgetting, and spinning false narratives rather than challenging and overcoming. But most of all, I fear that metaphors being invented and deployed are a way of avoiding a confrontation with those who are truly responsible for mass destruction.

July 18, 2015: A viral hashtag once again exposed the deep distrust between African Americans and US police. The hashtag #IfIDieInPoliceCustody emerged after the death of Sandra Bland. Bland was pulled over by a Texas police officer for failing to signal before changing lanes, and cops detained her after, they claim, she assaulted an officer. Three days later she was found dead in her jail cell. Police say the 28-year-old Black woman killed herself, but family, friends, and people on social media do not believe the story—in large part because Bland had just moved to Texas to start a job as a college outreach officer.

While #IfIDieinPoliceCustody is not directly linked to Wojnarowicz’s “If I Die…” statement, I begin with it because police brutality against Black communities continues to be our most pervasive public health emergency. Just as #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) became a unifying narrative frame connecting anti-Black racism to the history of slavery, debt bondage, segregation, and a punishment system geared toward the degradation of Black lives, #SayHerName and #IfIDieinPoliceCustody have also amplified the BLM movement.

In June 2020, during the first wave of the novel coronavirus pandemic and worldwide BLM protests following the police killing of George Floyd, several professors of public health and officials in major cities in America began to declare racism as a public health emergency. They argued that racism is built into institutional and structural mechanisms, such as residential segregation: “Where you live, for most Americans, determines where you go to school and the quality of education you receive,” scholar David R. Williams noted. “Where you live determines the quality of your neighborhood environment. Where you live determines even the quality of city services that you have access to. So, in many profound ways, your zip code is a powerful predictor of the factors that drive health.” From birth rates to death rates to places of residency and everything in between, racism impacts all levels of public health. As Williams concluded, “We have gotten to the point where we can no longer tolerate such behavior that is literally killing people.” Enough is enough.

March 14, 2018: During today’s national student walkout to advocate for gun policy change, a protester carried a sign that read: IF I DIE IN A SCHOOL SHOOTING DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE CDC. #IfIDieInASchoolShooting circulated widely on social media in the following weeks, after other school shootings transpired. In another direct reference to Wojnarowicz, Leah Ogdon wrote on Twitter, “The news will talk about me for a while and then forget about me. I will never get to graduate college, become CEO of a company, or start a loving family. If I die, I want my body to be thrown on the steps of the capitol building.”

The parallels between the FDA’s lack of AIDS research in the 1980s and the CDC’s ongoing inaction to prevent yet another ongoing public health crisis—gun violence—is striking. We can fault the Reagan administration for the former and Arkansas congressman Jay Dickey for the latter. In 1996, the Dickey Amendment passed in congress and effectively ordered the CDC never to fund research that could be seen as advocacy work for gun control.

By and large, the amendment passed because of the National Rifle Association’s lobbying efforts—the notorious organization claimed it discovered anti-gun bias in previous CDC-funded studies. And then, in an inexplicable turn of events, congress members took the exact same amount allocated to gun-violence research ($2.6 million) and reserved the funds for researching traumatic brain injury. Since 1996, the American Medical Association and the American Public Health Association have shown again and again that gun violence is a public health problem. After the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, president Obama signed an executive order commanding the National Institutes of Health to take up the study of gun violence. It never happened. More recently, a bill passed in May 2018 now allows the CDC to study gun violence, yet it doesn’t reverse the Dickey Amendment and there’s a debate about proper funding behind it. Essentially this means that it’s still up to lawmakers to balance Second Amendment rights with scientific data. In the spring of 2020, there were frequent news reports and commentaries on the spikes in gun sales all over the US. A June 2020 study found that gun owners were nearly four times as likely to die by suicide than people without guns, even when controlling for gender, age, race, and neighborhood.

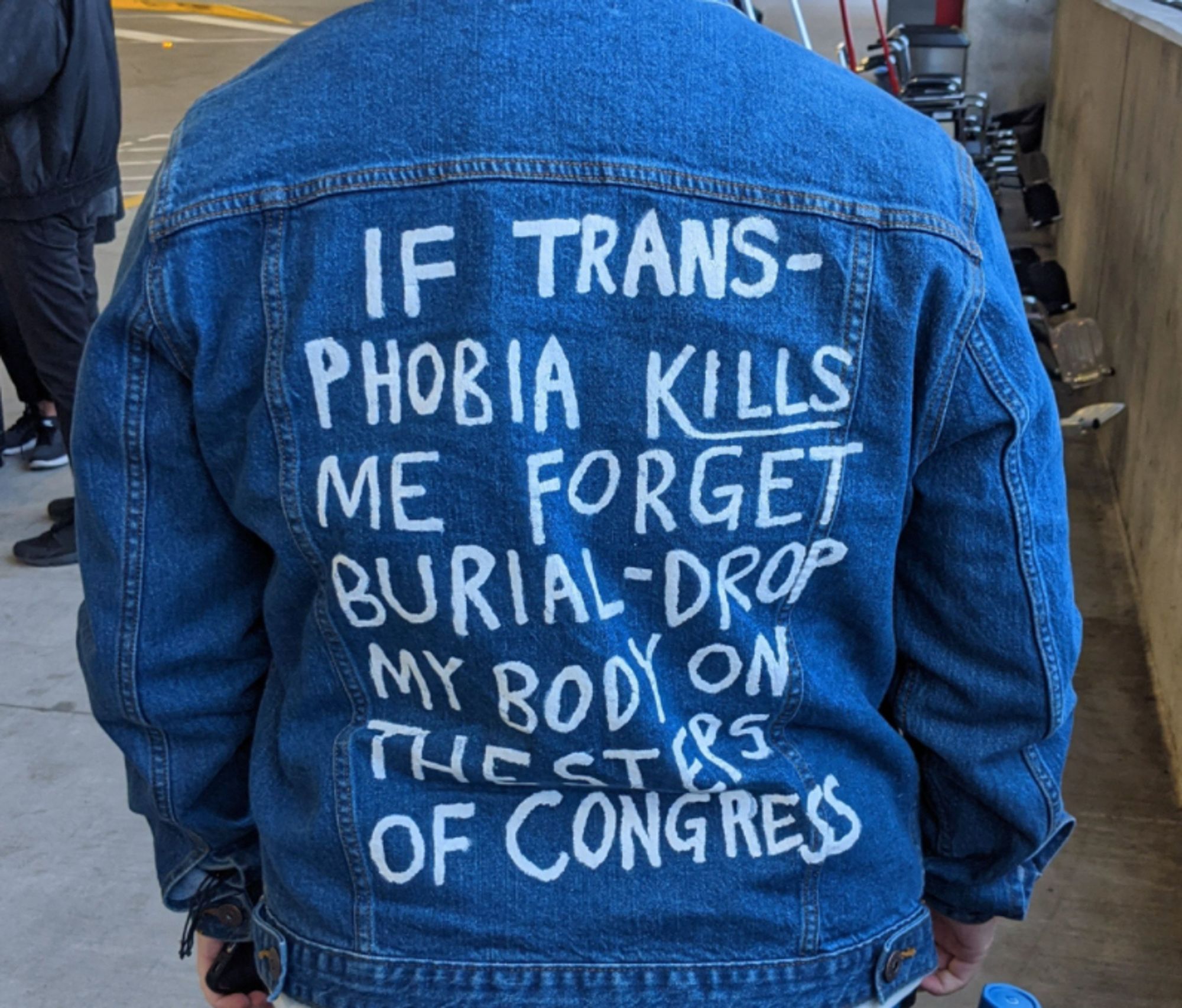

December 1, 2019: IF TRANSPHOBIA KILLS ME—FORGET BURIAL—DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF CONGRESS, via Instagram at the Nashville airport.

One thing the CDC considers a public health issue: suicide. According to a 2015 report, nearly one-third of lesbian, gay, and bisexual high school students had attempted suicide at least once in the prior year compared to 6% of heterosexual youth. A study published in 2018 found that gender nonconforming youths are at even greater risk, with more than half of the transgender male teenagers attempting suicide over the three years they were followed.

Despite these reports and the rising rates of violence against trans individuals in the US, states continue to introduce transphobic measures to chip away at transgender rights, including criminalizing medical professionals who prescribe hormone treatments to minors. Other proposed and recent measures include prohibiting transgender people from changing their birth certificates to match their gender identities; banning transgender athletes from playing on sports teams that do not correspond to their sex assigned at birth; and making it illegal to perform gender-affirming surgery.

March 24, 2020: The New York chapter of ACT UP and Housing Works collaborated on a face mask: “If I die of Covid-19—forget burial—drop my body on the steps of Mar-a-Lago.”

I’d been waiting for the Wojnarowicz text to pop up again, but I didn’t think the comparison of AIDS to the novel coronavirus would be so controversial. In an April 2020 op-ed for the Washington Post, professor Paul Renfro commented on the ACT UP/Housing Works mask: “While the novel coronavirus and HIV/AIDS should certainly be placed in conversation with one another, the notion that the former closely mirrors the latter is overly simplistic and problematic,” he wrote. “Yet the gap between the two can always shrink if the president and others continue to couch the coronavirus pandemic in racist and xenophobic terms—and if rich and famous Americans continue to obtain testing and treatment while others go undiagnosed and untreated.” Unfortunately, by then the gap had already shriveled. Trump repeatedly linked Covid-19 to Chinese and East Asian societies (in calling it the “Chinese virus” and “Kung flu”), which has, in turn, stoked violence and harassment in the US. Through that othering, fearmongering, and stigmatization, the coronavirus and AIDS share some, and probably many more, similarities.

Avram Finkelstein, artist and founding member of the Silence=Death and Gran Fury collectives, recently wrote that “The question of whether AIDS and Covid-19 are comparable, is a question with many answers. Placing aside differences in rapidity of transmission and universality, both pandemics have been molded by institutional lies, intentional neglect, and political subtext. The American agencies responsible for disease surveillance and drug research and approval remain institutionally entrenched, and mass graves of Covid-19 patients have been excavated on Hart Island in New York, where the bodies of the AIDS dead were buried when their families didn’t/wouldn’t/couldn’t claim them.”

I wonder if, decades from now when we look back at 2020, we’ll say that the connections between Covid-19 and AIDS seemed almost formal in the beginning—lies, neglect, subtext—but in the end they had nothing in common. As artist Robert Gober recently put it: “Nobody was banging on pots and pans at 7 o’clock during the AIDS crisis.”

October 11, 1988: “Our takeover of the FDA was unquestionably the most significant demonstration of the AIDS activist movement’s first two years. Organized nationally by ACT NOW to take place on the anniversary of the March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights and just following the second Washington Showing of the Names Project quilt, the protest began with a Columbus Day rally at the Department of Health and Human Services under the banner HEALTH CARE IS A RIGHT and proceeded the following morning to a siege of FDA headquarters in a Washington suburb.” —from Douglas Crimp’s AIDS Demo Graphics.

Nearly a thousand people attended “Seize Control of the FDA” in Rockville, Maryland, on October 11, 1988. ACT UP, which formed in 1987, had been conducting teach-ins for the rally in the months before. “I think they did them at P.S. 122 . . . I remember these big fat handbooks and all this research,” recalled the artist Zoe Leonard, adding,“I basically walked in and then within like two weeks or three weeks was actually understanding the landscape of AIDS in a way that I’d never understood it before.”

Wojnarowicz drove down from New York with his partner Tom Rauffenbart and Leonard, who was then twenty-seven years old. Leonard had met Wojnarowicz when they were both working at Danceteria in 1980. By 1988, they had formed the Candelabras, an ACT UP affinity group. Each group—comprising five to fifteen people—was tasked with coming up with its own action and making its own props for the FDA protest. ACT UP had already held a few die-ins, wherein protestors would lay down on the ground; accordingly the Candelabras came up with foam-core and painted tombstones for protestors to hold. Slogans written on them included “AZT wasn’t enough” and “I got the placebo."4 In her brilliant Wojnarowicz biography, Fire in the Belly, Cynthia Carr notes that he and Wojnarowicz were arrested that day along with 176 others—one person was charged with assaulting a police officer and the other 175 were charged with loitering. According to a Washington Post article, “A glass door and two windows were shattered, and organizers said six activists managed to sneak inside the building for a brief period. The only reported injury was a police officer’s scraped nose.”

Crimp, who certainly knew of Wojnarowicz’s art though they were not friends, observed that the protest’s success “can perhaps best be measured by what ensued in the year following the action. Government agencies dealing with AIDS, particularly the FDA and NIH, began to listen to us, to include us in decision-making, even to ask for our input.” As I stated in the beginning of this essay, by 1987 more than 47,000 people had already died in the US of AIDS. Many of the protestors wore T-shirts that day designed by ACT UP’s Majority Actions Committee that read:

WE DIE—THEY DO NOTHING.

In smaller text they were listed: Ronald Reagan, George Bush, Michael Dukakis, the NIH, the FDA, the U.S. Congress, the Congressional Black and Hispanic Caucus, our national media, and our national minority leaders.

Wojnarowicz died at age thirty-seven on July 22, 1992 in New York. One week later, an ACT UP affinity group called The Marys, who were known for organizing bold actions, prepared a demonstration for him in the East Village. (The Marys comprised, among others, Joy Episalla and Carrie Yamaoka, also of the lesbian art collective fierce pussy.) This was the first “political funeral” in a series that came out of the crisis. In the years following Wojnarowicz’s death, Rauffenbart scattered his ashes in several meaningful places, including on the lawn of the White House: On October 13, 1996, during ACT UP’s second Ashes Action, Rauffenbart climbed the fence in front of the presidential palace and threw some of Wojnarowicz’s remains over. As for the jacket, Wojnarowicz was not known to wear it after the FDA protest and it’s never turned up since 1992. According to sources, Rauffenbart—who passed away in 2019—did not know of its whereabouts.

*The author wishes to thank Anneliis Beadnell for sharing her expertise and speaking with the Wojnarowicz estate on her behalf.

Endnotes:

1. The former president was advised by Dr. Anthony Fauci, who became director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in 1984. He encouraged Reagan to act swiftly.

2. For more on viral modes of cultural production and physical epidemic, see Gregg Bordowitz, General Idea: Imagevirus. Cambridge: Afterall Books (MIT Press), 2010.

3. Burroughs once compared Wojnarowicz to François Villon, poet of “the outcast, the thief, the whore.”

4. Dr. Fauci’s work on the regulation of the human immune system was credited with helping to reveal how the HIV virus destroys the body. He led clinical trials for zidovudine (aka AZT), the first antiretroviral drug to treat AIDS.

Subscribe to Broadcast