The Future is Bright?

On my first day in Basel, I hole up in our Airbnb to work on a story about a smaller art fair in Moscow. I am sharing the flat with Sanaz Askari, founder of a nomadic platform for contemporary art exhibitions called The Mine, art collector Nigel Wilkinson, and Hugo Vitrani, a curator at Palais de Tokyo, who we never saw. This was the first time I wasn’t on an official press trip for Art Basel, so I could take my time and take it in. While I was excited to see what the mega-fair had in store for those who could make the pilgrimage to Switzerland, I was also reluctant about joining the art industry’s frenetic pace after a cataclysmic interruption.

Upon my entry to Messeplatz, there was an eerily jubilant air. I was almost rolled over by acrobatic dancers in shimmering leotards moving inside transparent, sea-urchin-textured orbs, as part of Monster Chetwynd’s outdoor performance, Tears. I then explored Basel Unlimited, the fair’s section for oversize art, including Urs Fischer’s Untitled (Bread House) (2004-6), a 20 x 16 feet, 3-million-dollar wood-and-bread house that is replenished with fresh loaves each time it is installed. It felt like the stuff of fairytales — the H.C. Andersen nightmarish kind — and I found myself wondering if I had wandered down the wrong path in the artworld forest myself. The sense of monumentality (and waste) in Unlimited felt unnecessary, though commercially successful: Thaddaeus Ropac sold a Robert Rauschenberg’s Rollings (Salvage) (1984) for $4.5m in an early sale, and Dan Flavin’s untitled 1974 light installation sold for $3m.

In my decade of writing for and editing art publications, I had never been to this mother of all fairs. In my former position as editor of Dubai-based art magazine Canvas (until the pandemic hit and the publishing industry plunged even further into crisis), I was predominantly focused on the Middle East — ‘the region’, as we say in the Gulf — which expanded to South Asia during my stewardship to uphold a Global South framework.

Among the 272 galleries from 33 countries at Art Basel this year, only two galleries, Sfeir-Semler gallery and Marfa gallery, represented Middle Eastern and Lebanese artists respectively. Also only two galleries were from India, Chemould Prescott Road and Experimenter. The inherent Eurocentrism of the fair was inadvertently acknowledged by Marc Spiegler, Art Basel’s Global Director, in a press conference. After countering press claims that there were no visitors from Asia and North America due to COVID travel restrictions, Spiegler stated that, “on the one hand, this is a more European fair than ever. On the other hand, this has always been a European fair. Basel’s strength has been the fact that it lies at the center of Europe.”

There also seemed to be a disconnect between artists showcased from the Arab world. On display was Etel Adnan’s Le Soleil Toujours (2020), a joyful mural intended to raise morale amid severe crisis in her native country Lebanon, and Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s The Whole Truth (2012), which expands on his experiments on the forensics of voice analysis in lie-detection procedures and migrant policies. Adnan was born in 1925 and Hamdan was born in 1985; there was little in between these ends of the generational spectrum.

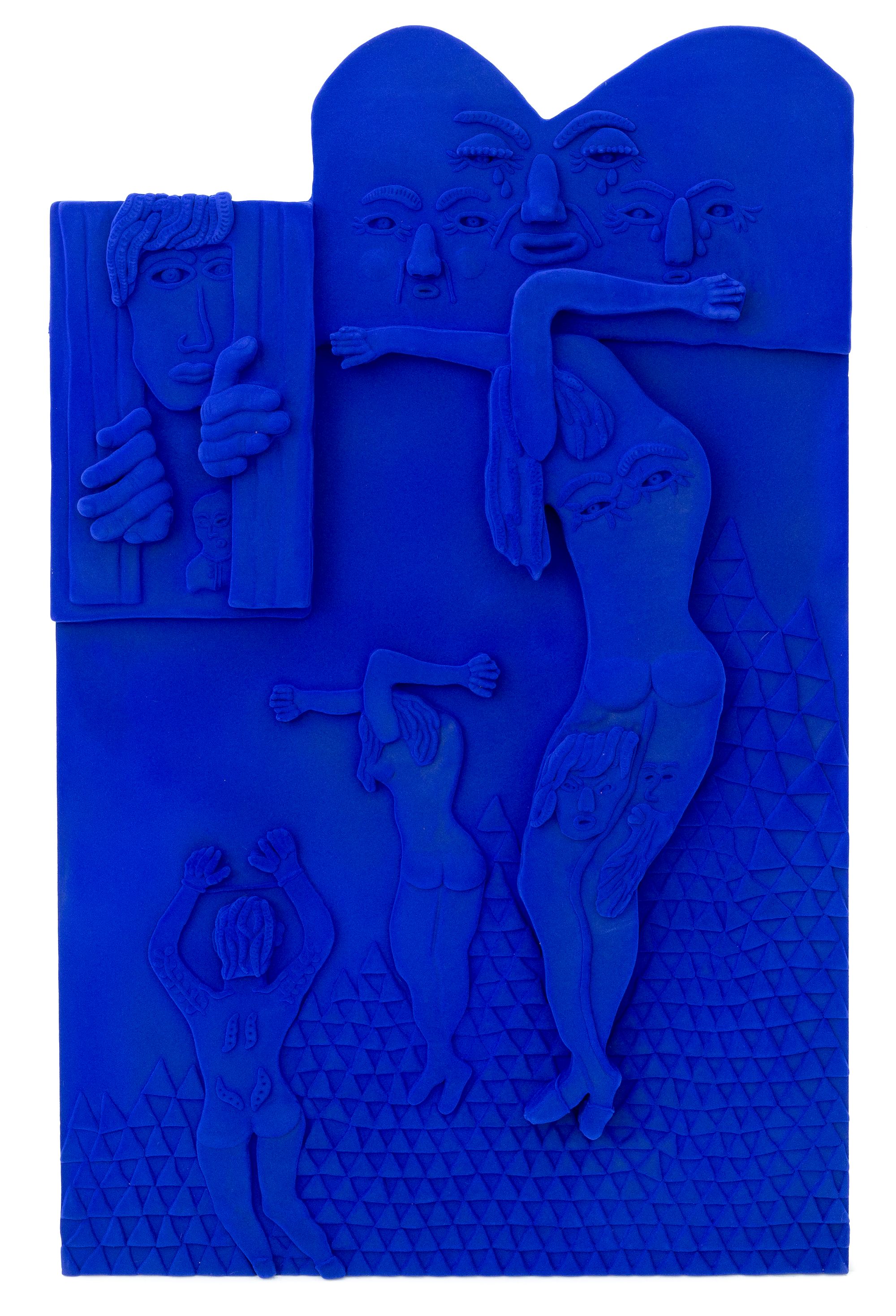

As Sanaz and I walked through the fair, she pointed to works by Iranian artists that struck her eye: the late Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s Third Family (2011), geometric sculptures in mirrored glass emblematic of her signature reverse painting technique in Unlimited, and rising artist Borna Sammak’s Not Yet Titled (2021), a swirly, fantastical landscape with dispersed American flags in heat-applied t-shirt graphics and vinyl at Sadie Coles HQ’s booth. As for Tehran-based artists, there was Mostafa Sarabi’s The sea, which can't be seen from the coast (2020) at Delgosha Gallery, paintings of idyllic pea farms and sunset vistas, and Nazgol Ansarinia’s Connected Pools (2020) at Green Art Gallery, modular-looking pastel-blue plaster blocks that allude to empty pools (and dreams) in Tehran’s middle class neighborhoods. Paris-based Mamali Shafahi was showing Heirloom Velvet (2020) at Dastan’s Basement, epoxy resin relief sculptures of scenes conveying kinship and metamorphosis. Yet only Sammak and Farmanfarmaian were in Art Basel, while Sarabi, Shafahi and Ansarinia exhibited at Liste and June, satellite fairs at the Messeplatz.

There were signs of a more collaborative spirit brought about by the pandemic, namely the fair’s “solidarity fund” of 1.5m Swiss Francs that enabled galleries with strong sales or better financial standing to subsidize other galleries. Yet it still remains to be seen if the innately exclusive industry can become a space that’s convivial and supportive. It likely surprises no one that most of the highest six-figure sales were of American male artists (among them, Phillip Guston sold at $6.5m and Keith Haring between $5 and 5.5m), with the exception of a Black-American artist (Mark Bradford at $4.95m) and a woman artist, also American (a painting by Helen Frankenthaler for $3m).

Despite Spiegler’s reference to the fair’s transformation in terms of “an acceleration towards really embracing the digital in a way that this industry had not,” I was surprised to see only one booth (Galerie Nagel Draxler) selling NFTs. Curated by Kenny Schachter, it was replete with Anna Ridler’s video installation of tulips that morph with the price of Bitcoin, and Olive Allen’s CGI rendering of destroyed NFTs, a brilliant visualization that counteracted the perceived timelessness of digital artifacts. I almost missed it, if it wasn’t for the tacky wallpaper emblazoned with the bright red and blue logos “NFTism.” But perhaps Art Basel, despite its commerce-driven model, isn’t the reference point for new ideas.

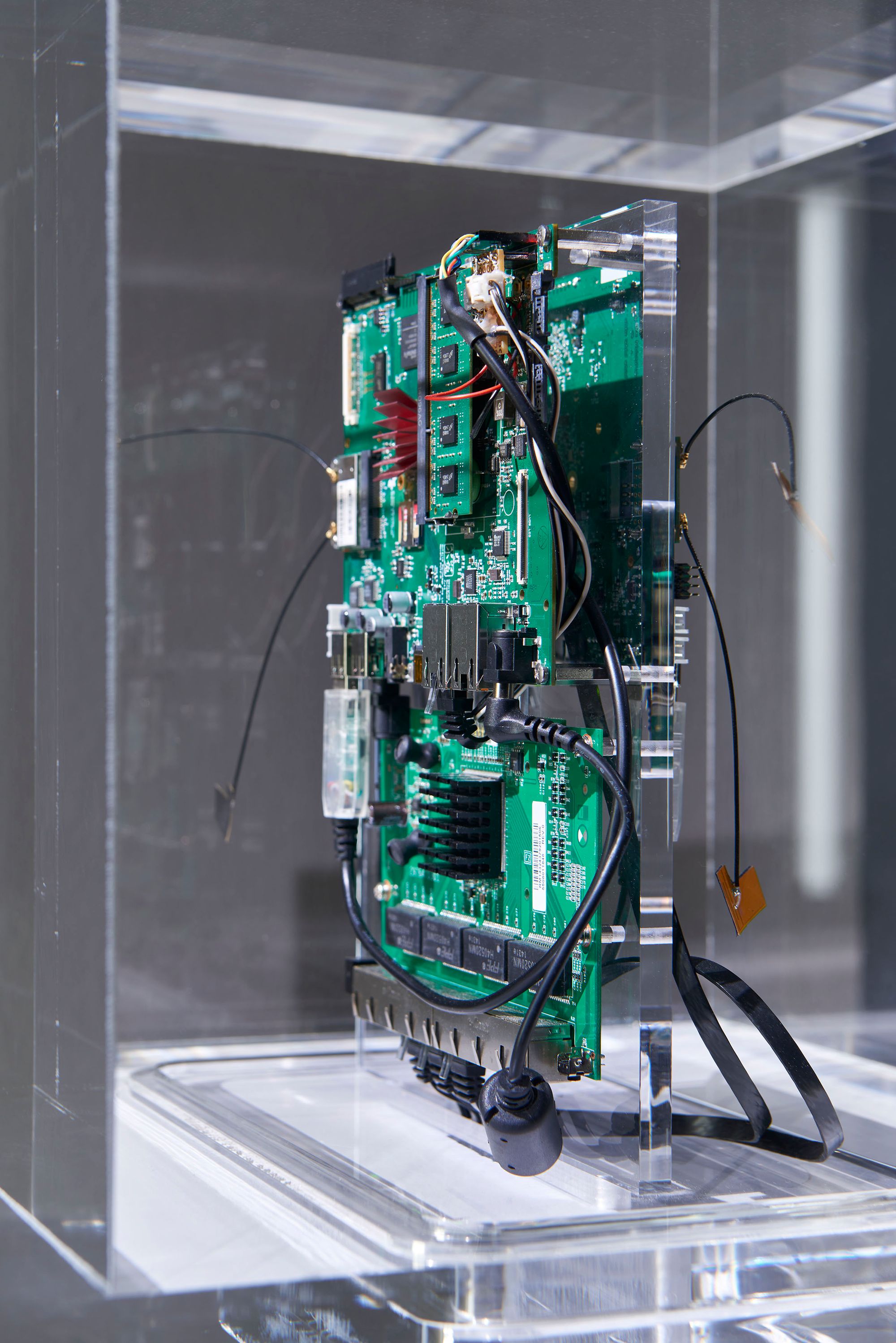

That’s not to say there wasn’t plenty of digital art such as Upstream Gallery’s showcase of 90s net art pioneers JODI, including their first website in 1997 (shown at Documenta X in Kassel), and more recent work \/\/iFi (2017-2019) that has been exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2018. The booth was curated in a seamless flicker of scrolling screens that lined the walls, where works by early internet artists corresponded with newer ones to display a movement developing since the onset of the World Wide Web. Further contextualizing our digital age was INFORMATION (Today) at the Kunsthalle Basel, conceived in response to MOMA’s landmark 1970 Information show. There were works that situated our current state of affairs in forbidding and playful ways, including Laura Owen’s smart painting (Untitled [SMS +41 79 807 86 34]) (2021), where a pixelated, upside down pink cat responds to your SMS’es, and Trevor Paglen’s Autonomy Cube (2015), a motherboard-like sculpture that accesses a Wi-Fi hotspot free of tracking using the global network, Tor.

Despite the UBS art market 2020 report claiming that more women, and millennials, are collecting art, Sanaz often pointed out that we were the few women among middle-aged, white men in every room, launch, or opening. We were almost always the only ones from the Middle East. This was true during a particularly hard-to-watch Matthew Barney performance, Catasterism in Three Movements, at the Schaulager Laurenz Foundation. Dutch athlete (Jill Bettonvil) appeared as a sniper, dressed in white and strapped with a hunting rifle, and stood in a tense face-off with an Indigenous hoop dancer from Alberta’s Bigstone Cree Nation (Sandra Lamouche). Lamouche twirls in a complex hula-hoop configuration and the piece ends. Barney, who included an experimental orchestra composed by Jonathan Bepler as part of the performance, was drawing on themes of his film Redoubt (2018). I learn this in a handout, which also references the sublime as a cultural construct, the mythology of the American Frontier, a nation born out of extreme violence to nature. But without this background, the experience was abstruse and confusing. Even with my decade reviewing art, I’m sometimes left with the feeling that a secret has been withheld from me. Like when you’re in a crowd and everyone is familiar but you don’t really know anyone.

Like my experience at the invitation-only fair party (the card read “FAIRCLUB.DIRECTORSCUT”) in a decrepit industrial building. Surrounded by writers, gallerists, and Art Basel reps, including Spiegler, who had replaced his daytime navy suit for a party tracksuit, I again wondered if I had strayed from the path. Here I was, lured by the hype of this party into a different kind of black box, while DJ Tennis mixed aggressive tunes, reminding me of the last time I saw him on a boat afterparty in Dubai. Amid the high-octane raucouses of the event, I thought of Mario García Torres’s It Must Have Been a Tuesday (2020), which attempted to find language for our former inertia: 164 photocopies with the words “Cerrado temporalmente” (or ‘temporarily closed’ in Spanish), marked the perimeter of a room, their repeated copies disintegrating into the illegible abstraction.

Others tried to find a language for the future, such as Lebanese artist Vartan Avakian’s A Sign For Things to Come (2021) in Marfa gallery’s solo presentation as part of Art Basel’s program, Statements. A glowing display of neon tubes placed inside blood-orange polysiloxane formed Cy-Twombly-like 3D squiggles. Installed on plinths, they carried the ghostly air of a public memorial or cemetery. It was a stunning distillation of the political volatility and economic collapse of a country, when there’s not enough electricity to go around and light up failing businesses. “These used to be the signs of shops and neighborhoods in Beirut. Now they are signs of an era that no longer exists,” Vartan told me. “In the future, maybe people won’t understand our languages.” The discarded neon remains appear fossilized, as abstract signs, haunting archives for an unknown future.

In Basel, I had run into Swiss collector Maja Hoffmann, Belgian collectors Frédéric de Goldschmidt and the more contentious Alain Servais, and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Upon my return to Dubai’s contemporary art scene, I was no longer surrounded by well-heeled European art patrons, but in the midst of the high-tech hype of EXPO 2020 and other openings. The new Volte Art Projects launched in late September with a group exhibition, Sublime Convergence, that explored a futurity that was more machinic than manmade. Rejecting the notion that nature is in opposition to technology, this exhibition embraced technology as an interface of the natural.

As is befitting a city of Biggest and Bests like Dubai, there is a star-attraction in the show that includes Wim Delvoye’s Tower (2009), a neo-Gothic computer-generated structure at once both ancient and futuristic. I engaged with the works at Volte alone, and they spoke back to me in tongues. Upstairs was William Kentridge’s Sibyl (2020), a lyrical, animated flipbook recalling the confounding prophecies of an ancient priestess. All I could sense was the unknowability of our environmental futures. As the narrator declares: "Forget the smell of the eucalyptus leaves. The smell of the wind (as it once was). Let them think I am a tree, or the shadow of a tree. A doubt, a shadow of a doubt. There will be no epiphany.”

Kentridge’s inky, lithe silhouettes reminded me of Kara Walker’s work, which I experienced during Art Basel at the Kunstmuseum Basel’s exhibition A Black Hole Is Everything a Star Longs to Be. Drawing from her personal archives and writing, Walker presented a disturbing look at racial histories, subjugated bodies, and bondage in an attempt to rearticulate and reclaim them. “Be scary and disenfranchised and you will make great art,” she proclaims in one text. Another fragment that remains with me was painted next to a charcoal-like drawing of a hanging man: “True painters understand tradition and how to upend it (while never changing anything).” This sentiment felt reflective of the artworld at large, which somehow simultaneously constantly reinvents itself and stays the same. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast