Anthony Banua-Simon on Sweetness and Power

White Heat (1934)––the first Hollywood production on the Hawaiian island of Kauaʻi, directed by Lois Weber––emanates like a colonial fever dream, doused by fuels of sexual desire, fear, and paranoia. One night, through booze-bleary eyes, a plantation owner named William Hawkes sees the plantation worker Leilani bathing on the beach. Roused by his lust, he runs across the sand to greet her; she falls into his embrace, and their love affair commences. Later, Hawkes travels to San Francisco for a planter’s convention, and returns with a high-society woman as his wife. Perilous jealousy and betrayal ensue in all directions, and the film ends with the ripe sugar cane fields scorched by a kerosene lamp. The review board censored the film, fearing that the blazing fields would flicker too suggestively in the eyes of its class-conscious viewers.

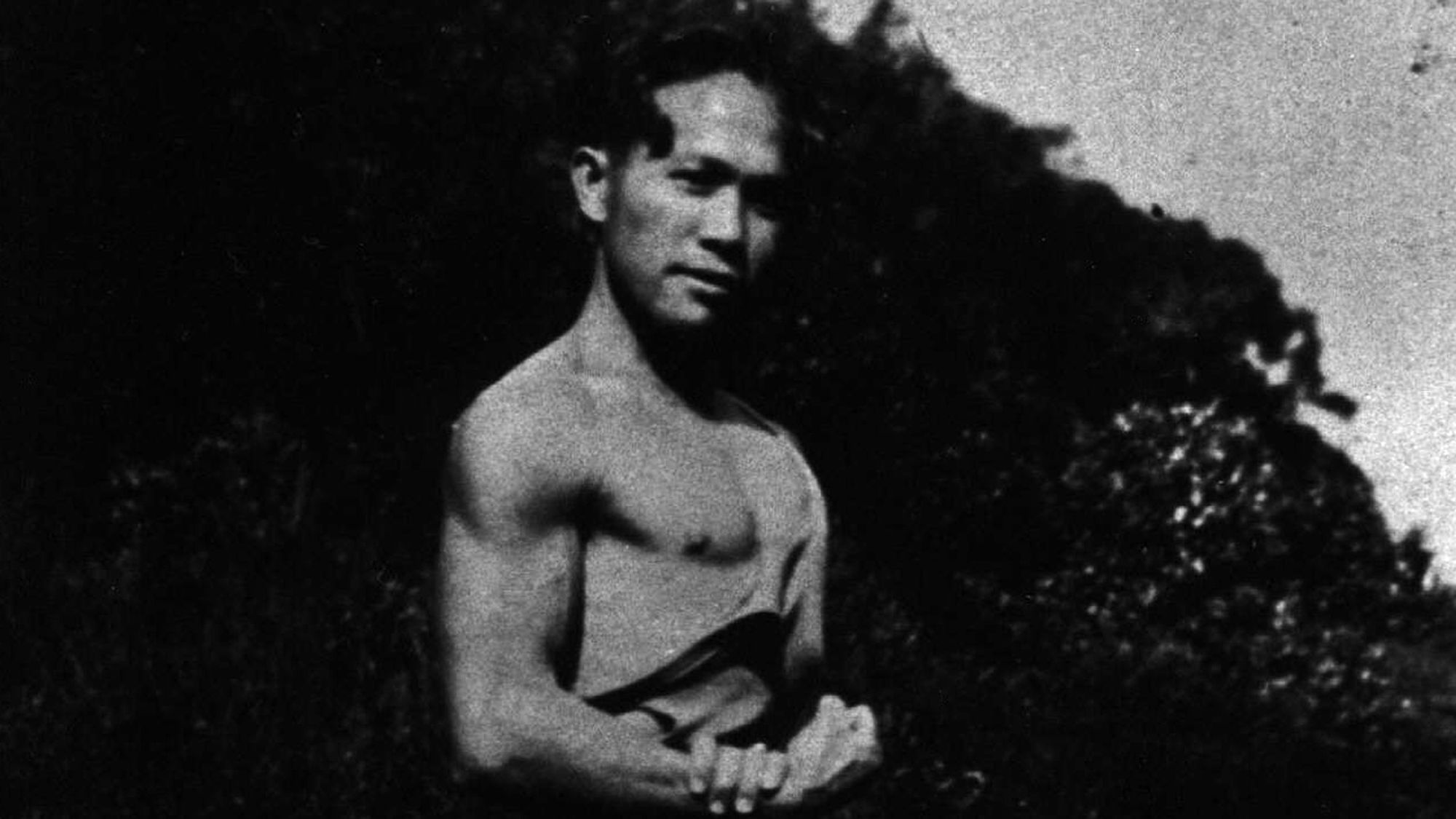

Anthony Banua-Simon learned of a rumor that his great grandfather Albert appeared as an extra in White Heat, also known as Cane Fire. A cannery worker and labor organizer, Albert was the start of four generations of his family who were to be employed by Alexander & Baldwin, one of the Big Five sugar and pineapple companies that controlled Hawaiʻi’s economy for over a hundred years. This legend is one thread Banua-Simon pulls in his film Cane Fire (2020), which examines––in personally granular and historically broad strokes––the collusions between the agricultural industry, Hollywood, and the US government to exert control of Hawaiʻi. These themes recur in his films, as with Third Shift (2014), a short that accompanies two former workers of the now-defunct Domino Sugar Refinery in South Williamsburg, which at one point produced half of the nation’s sugar. Astonishingly, this too is connected to Banua-Simon’s family: his great, great grandmother worked in the Puerto Rican sugar fields that shipped the raw sugar to Domino.

Banua-Simon and I met for sugarcane juice, at the NYC Chinatown beverage shop Sugarcane Daddy. We spoke about tracing the history of labor through one’s family, the exercise of colonial power through culture, and using strategies in documentary filmmaking to undermine so-called truths.

–– Minh Nguyen

Let’s start with White Heat.

Though Weber’s White Heat has long been identified as the first Hollywood production on Kauaʻi, there is little information about it. I think recent increased interest in Weber has surfaced more details, but not an actual print. When I interviewed Art Umezu, the Kauaʻi Film Commissioner at the time, he said that one of the first things he wanted to do in office was find this lost artifact. It would be such a unique historical document that shows Kauaʻi’s plantations in this era.

There’s actually no definitive proof that my great grandfather was in it. The entire shoot only lasted two weeks, mostly in the nearby Waimea Plantation, but they visited other plantations to get coverage of workers during their daily operations. Even the cane fire climax was filmed from the routine of burning the cane to better access the stalks afterward.

Regardless, I thought it was an interesting starting point for both my family’s story and Hollywood’s relationship to Kauaʻi, which would continue to remain entangled in the present day. My great grandfather was dealing with the material conditions of plantation life that the production was simultaneously documenting, dramatizing, and later censoring.

You make surprising, yet seamless, connections between the sugar companies and the tourism industry that Hawaiʻi is known for today––like the Big Five’s PR strategy of enlisting Hollywood to make Kauaʻi a backdrop.

Hawaiʻi––Kauaʻi specifically––has been used by Hollywood in a variety of different ways, but it really started in the 1930s as a partnership with the Big Five sugar companies as PR after the rest of the world started hearing about the harsh labor conditions imposed by the companies. It’s what led to the creation of the “South Seas Fantasy” genre, a term first coined by historian Delia Malia Caparoso Konzett in Hollywood’s Hawaii, where Asian Hawaiian and Native Hawaiian residents were portrayed interchangeably as carefree and subservient to visitors.

Gradually, as the US government gained more control on Hawaiʻi, they used Hollywood to further their case for statehood leading to 1959 through the Office of War Information and the Hawaii Tourism Bureau, by pushing pro-military and tourism productions like the anti-communist propaganda Big Jim Mclain and the musical South Pacific.

The transition of power from the Big Five companies to the US government is a complicated one but both used Hollywood productions to sell their vision. It’s not to say films were the most important means of influence, but this is a film, so why not tell the story through other films?

Today we’re able to see the seams in these dated depictions, and the ideology is more blatant. But I also wanted to show the motive of US cultural hegemony is still here. The last phase I surveyed was contemporary user generated videos on YouTube that end up reflecting back these Hollywood myths––tourist vlogs, “plantation-style” lifestyles flaunted by seasonal residents, the appropriation of Native Hawaiian practices by New Age life coaches.

What was your research and interviewing process?

Two texts really energized the project: Moon-Kie Jung’s Reworking Race, about Hawaiʻi’s interracial labor movement, and The Autobiography of Protest in Hawaii by Robert H. and Anne B. Mast, which focuses on progressive activists in both the labor and sovereignty movements of Hawaiʻi. It also details historical instances of solidarity between working class and Native Hawaiian residents, particularly around housing issues.

As I researched, I came up with questions for conducting oral histories with people on Kauaʻi, branching from my extended family. It’s always surprising, the assumptions I gather through research that are confirmed or challenged through in-person conversations.

Documentary filmmaking can be a humbling process, and your conversations with people led by open curiosity will shape the result. With Cane Fire, I tried to be honest about where I was coming from and what I didn’t know, without being too self-flagellating. I didn’t want to make myself the main character in a narrative sense, but I also wanted to pull from my impressions as someone a bit removed from this history. I remember the exotic appeal Kauaʻi had on me when I was a kid, and I wanted to interrogate that.

Sugar is prominent in both Cane Fire and your previous documentary, Third Shift. Was this linkage deliberate?

The co-writer and co-producer of Cane Fire, Mike Vass, and I made Third Shift while in residence at UnionDocs in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It was part of the “Living Los Sures” project, which was an homage to the 1984 documentary Los Sures, about the surrounding neighborhood made up of predominantly Puerto Rican and Dominican residents at the time.

We focused on the Domino Sugar Refinery. While researching for this project, I thought about my extended family and how the sugar industry was responsible for their emigration from the Philippines and Puerto Rico to the Hawaiian islands. So in a way, I was following that migration.

Other parallels between the two projects became apparent, such as a long-organized labor struggle, the quick flip into luxury real estate after deindustrialization, and––in the case of the Kānaka Maoli activists at Wailua and Johnny’s Berry Street Community Garden in Williamsburg––the use of the land that defies market logic.

When Domino closed in Williamsburg, the industrial area along the East River was rezoned as residential practically overnight, resulting in a kind of hyper-gentrification. Families who lived in the neighborhood for several years were bought out, offered what seemed like a large sum of money for their houses but was minuscule in comparison with what developers knew they would gain in the investment. The refinery itself was converted into a luxury condominium made up of over 2,300 units.

In Kauaʻi, and across Hawaiʻi, there’s been a huge displacement of local residents over the years. A recent statistic states that ⅓ of Native Hawaiians live outside of Hawaiʻi because of the exorbitant cost of living. The influx of speculative real estate has raised the property taxes and other costs dramatically for working class and Native Hawaiian residents.

In the film, you walk through the old refinery, which is being developed by the real estate company Two Trees. You ran into some skirmishes with Two Trees, right?

To record inside the abandoned space, we had to sneak into the building with the help of a friend who had previously orchestrated an excursion there. The building had increased their security and there were guards doing active rounds––we had to hide while trying to get good footage.

We knew we couldn’t safely sneak Johnny and Frank [two former Domino workers and the main characters in Third Shift] into the space so we followed up with Two Trees to grant us access, which is the final scene in the film. At the beginning of the shoot, a representative gave us a tour and we all had to pretend we had never been there before!

From their previous interactions with a photographer, we knew that Two Trees imposes content restrictions by contract. We didn’t want to be tied to them in any way. We were able to film that one day without any obligation, but it was made clear to us that for further access, they would want further control of our film. We completely ended contact after that day. Two Trees badgered me over email to get Frank and Johnny’s contact for their own PR purposes. But I didn’t respond. They found Frank on their own eventually––you can see his interview in their project for Domino Park.

You have family ties to Domino, too.

My great, great grandmother worked in the sugar fields of Puerto Rico that shipped the raw sugar to be refined to Domino in Brooklyn. There was a hurricane that wiped out several acres of fields, which left people without work. The then-US-instated civilian governor of Puerto Rico after the 1898 annexation, Charles Herbert Allen, orchestrated a system of labor migration that brought one side of my family from Puerto Rico to Hawaiʻi in 1901, and that’s where our story continued. Allen later became the president of Domino.

It’s amazing that your story connects these seemingly disparate economies, in Kauaʻi and Puerto Rico and Brooklyn, but it’s also such a testament to how family stories are labor stories.

Third Shift mentions that Domino was the site of one of the longest strikes in US history in 1999, throughout twenty months. Cane Fire covers a long, embittered history of exploitation and organizing, like of companies that pitted different migrant labor factions against each other. Then it moves into the present-day with the Kauaʻi Division Director Pamela Green on the current weakness of union power and the importance of collective bargaining.

When I found a video of an ILA union meeting, shot by Domino employee Kenny Malcom in 1989, it was such a revelation to witness this diverse workforce, dialed in, unapologetic, and aware of their strength. Domino had just proposed a revised contract in response to a five-week strike, which was a precursor to the one in 1999.

When I was briefly a freelance employee at Vice Media headquarters, I actually worked in a building formerly occupied by Domino, across from where the 1999 twenty-month strike occurred. Workers at Vice Media recently started their own union in 2015 and are continually responding to the same age-old tactics by management. A further irony is that Two Trees and Vice’s branded content branch, Virtue, ended up collaborating on a project advertising the former Domino building’s future retail and office space.

In the recent nationwide resurgence of union power, in which workers have been responding to their mistreatment during COVID––while hypocritically being deemed ‘essential’––I see a parallel with Hawaiʻi’s labor history. In Reworking Race, Jung writes about the period in World War II when the US declared martial law and Hawaiʻi was basically under lockdown and prohibited from unionizing. After the conditions were lifted one year later there was an explosion of enrollment for Hawaiʻi’s ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union.) It speaks to the dual frustration and enthusiasm for collectivizing that can build up.

Looking at my cousins who are my age on Kauaʻi, I can see them disillusioned with a precarious system that worked for their grandparents' generation but isn’t serving them anymore. What really stuck with me was my cousin Dylan saying “I’m willing to put the work in,” in Cane Fire. He struggles to feel secure, and wears the onus of that feeling as a personal responsibility. They are so overwhelmed with the day-to-day that it’s hard to stop and evaluate or question the system they are in.

You’re working on something now that follows Cane Fire.

I’m currently finishing a short companion documentary called The Experiment Station, about the biotech industry on Kauaʻi. For several decades, it has used Hawaiʻi as an open-air testing site of lethal chemicals, which has impacted the environment and health of residents. The Experiment Station looks at how Hawaiʻi’s legacy of colonialism and extractive capitalism has emboldened these biotech companies to continue to function with impunity. There are already a few films on this subject, in a broader sense of challenging the science of GMOs, but I’ll be focusing on how biotech also specifically developed out of the sugar and pineapple industry here. ♦

Third Shift is currently available on the Criterion Channel.

Cane Fire will be released commercially in 2022 including a limited theatrical run.

Subscribe to Broadcast