Apple Incorporated

Who does nature belong to? According to U.S. case law, everyone. Natural phenomena are legally “part of the storehouse of knowledge,” “free to all men and reserved exclusively to none.” This line of thinking, unfortunately, is fundamentally incongruous with capitalism. So how do the enterprising sidestep this rule? One way is by copying nature and patenting the “inventions” they come up with.

When does an element or source become ownable? How does it transform from public to private, spirit to product, phenomena to property? This capricious, alchemical process is what preoccupies Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser’s new film. A Common Sequence is an observational documentary that takes us to three locations: a convent near Lake Pátzcuaro, Mexico where nuns farm-raise salamanders to make healing syrup; a high-tech apple orchard in Prosser, Washington, where human workers assist sophisticated robot harvesters; and the tribal homeland of the Cheyenne River Sioux, in South Dakota, where an organization called Native BioData Consortium is working to raise awareness around genomic data sovereignty. The film roams between these portraits, perforating whatever solid ideas we may have about labor, science, food, faith, and what is “common” to everyone.

On these topics, one can imagine a slick, pedantic documentary that claims to contain all the answers; in fact these exist by the dozens on Netflix. But A Common Sequence is not a simple film—rather, it's one that leaves room for awe. We watch the salamander, which can regenerate limbs, swim, and marvel at its existence. We see the sun rising over a lake, and are reminded of the magnificence of this everyday occurrence. Marx writes that only “the supersession of private property is the complete emancipation of all human senses and attributes.” This is a film full of the liberated sensations he was perhaps describing––they flash across the screen, winkingly, as glimmers of what could be possible beyond the bounds of transaction, ownership.

The artists and I discussed the film, which Broadcast is pleased to present for streaming. For maximal viewing experience, we suggest playing it on as large a screen as possible.

***

Where did you start?

We wanted to think through ideas of climate change and adaptation, but also a kind of ecological filmmaking that decenters the human.

The Basílica [de Nuestra Señora de la Salud] in Pátzcuaro was the first site that we learned about. Sister Ofelia, who you see in the film, and other nuns in the convent are breeding and caring for one of the world’s largest captive populations of the achoque, a salamander species that was once endemic to Lake Pátzcuaro but are now functionally extinct. They use the salamanders to make a medicinal syrup called jarabe, which they sell to the community to help sustain the convent. Their work with the salamander connects them with biologists and conservation efforts around the world.

So, from this site and this one specific animal, a nest of topics arose around it… this mixture of faith and science, ecological change and collapse, economy and adaptation.

The other sites came organically, after our first visit to the Basilica. I’ve worked intuitively before, but always on a smaller scale. On our first shoot we weren’t able to get access to the convent, and it began to feel like the project was off to a rocky start, but it was because of that redirection that we met the fishermen.

Our producer Graciela [Guerrero-Reyes] knew Don Mauricio and his family from working in the area and thought we should hear their perspective on the lake and the achoque salamander. Their stories of fishing and migrating to the U.S. completely reshaped the project. Shooting with them at night was our first touchstone for the film’s visual vocabulary. In Patzcuaro we developed the idea of engaging with a place through a single organism. It set up a logic for the film. The salamander was our first nonhuman subject, and the apple and AI would follow.

When we interviewed Don Mauricio and his sons, they mentioned that they had migrated temporarily to the U.S. for work. That story brought us to Washington and Tacoma, where we looked into the robotics work being developed in the agricultural industries there. I remember Mary Helena sending an image of one of the robotic claws at some point. In that same area, Joseph Yracheta, who eventually appears in the South Dakota section of the film, was giving a presentation about data sovereignty and his work in genomics with the Native BioData Consortium, and we realized he, Don Mauricio, and his sons all have Purépecha ancestry. It was another moment where a nest of interconnected topics spun out of a single location.

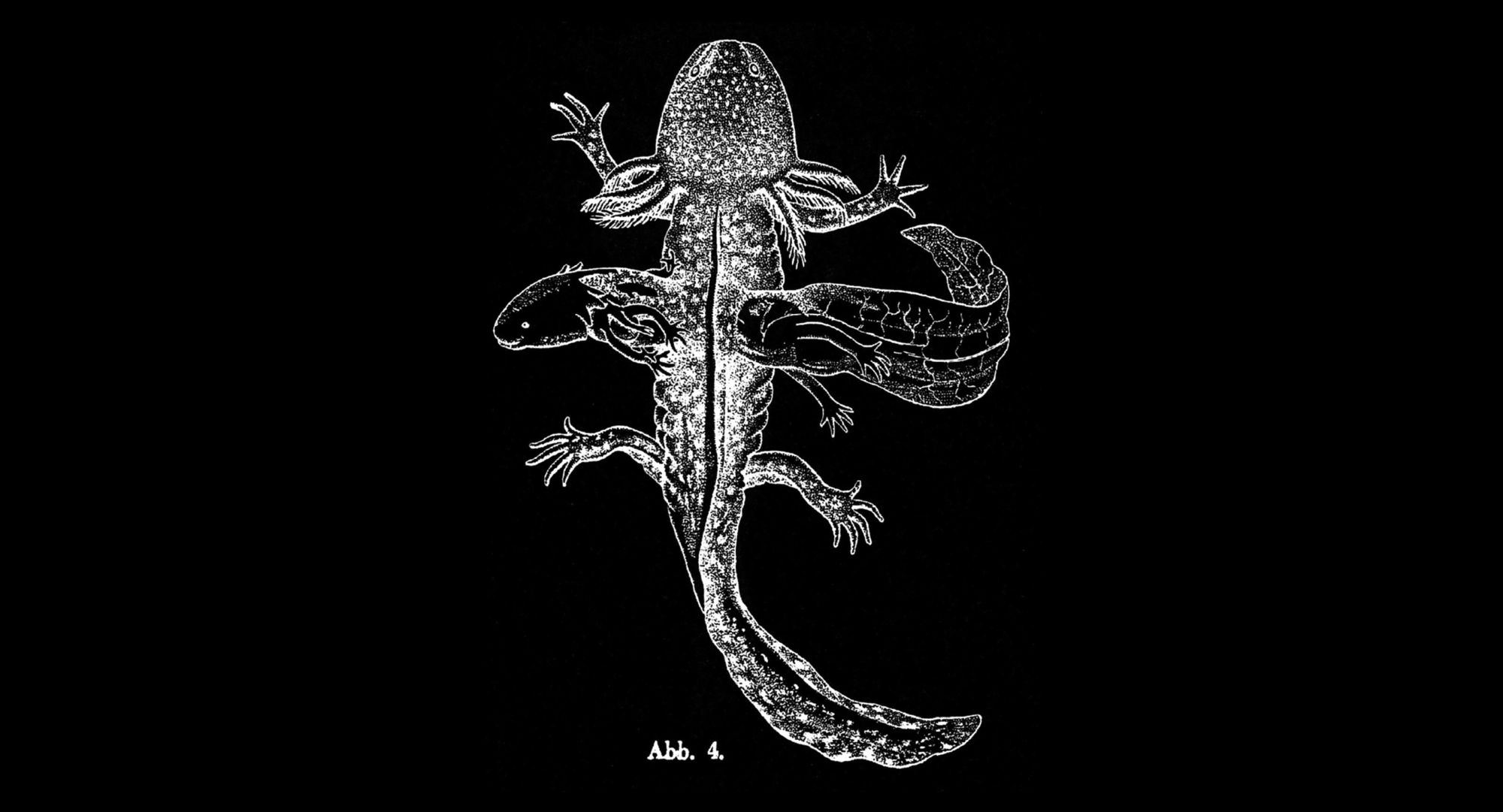

We were looking for an equally complex site to pair with Lake Pátzcuaro. But our thinking shifted from something comparative to the unexpected offshoots from the stories of the lake: the diasporic Purépecha community in Washington, the role of genetics in plant patenting and how that relates to the axolotl as the "lab rat" of genomic research, and threads of labor and extraction more generally. We were really struck by the visual similarities of the spliced axolotl and the grafted apple varieties, and the parallels between limb regeneration and the robotic hand in the agricultural engineering lab.

Still from A Common Sequence (2023), directed by Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser.

Courtesy of the artists

Still from A Common Sequence (2023), directed by Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser.

Courtesy of the artists

Still from A Common Sequence (2023), directed by Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser.

Courtesy of the artistsI’m from Washington, and thought, of course this robotics apple harvesting center is there. I had never seen that kind of machinery before.

Us either. It was exciting to see what the science looks like now, where agriculture is heading. These technologies and labor practices have such an impact on our lives and aren’t really considered or seen. There's something especially visceral about a robot picking fruit. I think of it as such a sensorial act.

One aspect I was struck by is the bareness of music. With these topics, I could easily imagine a documentary that goes either the doomerist or tech-evangelist route. But I felt like you guided with a light hand. The film conveyed information and showed me things I didn’t know, but still left room for mystery and awe. That balance seems difficult to strike.

We ultimately wanted to explore the ideology behind the present situation, like what has gotten us here, as opposed to coming down with judgments. We had a notecard on the wall of our studio that read “no heroes and no villains.”

We aren’t interested in condemning scientific or technological research, but in interrogating it. And the divide between the natural and non-natural world, a division that is somewhat arbitrary and has shifted through history. And where it falls has become a key to ideas around ownership and privatization, particularly in the U.S.

Not creating an overly simple story of heroes versus villains, but also not wanting to let anything remain neutral. A tool is not neutral, a technology is not neutral.

What have the responses been?

Some have talked about it as feeling hopeful, others as feeling apocalyptic. Or that it opens up rabbit holes for their own research. But some of my favorite responses have been from people who sought out the film because it relates to their own work, like conservationists, biomedical researchers, software designers. There’s a lot of siloing in expertise.

The fishing scene at the end is so gorgeous, when the sun dramatically radiates light over the lake. I sensed that what I was watching was likely a technical trick, but at the same time, I wasn't sure.

This sense of spectral, almost religious, enigma pervades the film. The scene made me think about how conversations around labor exclude the spiritual aspects that people may experience in their work. It makes sense that this aspect isn’t prioritized, as struggles for justice are oriented around higher wage compensation, liveable work conditions, life-or-death issues. I was just reading about farmworkers in Florida dying on the job from heat exposure.

Fair wages and heat protections were main concerns for the United Farm Workers when we spoke with them in Washington. They still are. Awareness of the punishing conditions in the field is a primary concern for Manoj [Karkee] and everyone else at the WSU lab where they are developing the automation technology.

Don Mauricio talks about what we’re calling the spiritual aspects––the reciprocal or symbiotic relationship between the fishermen and the lake. He talks about stirring the water of the lake, which aerates it and creates change in the ecosystem. And about his interactions with the water as play or that the movement, in itself, is medicinal.

There’s a trope within ethnographic film, the long take of a person working, right? We were aware we were engaging with that tradition and wanted Don Mauricio’s presence in the film––his work as labor, but also as expertise, artform and medicine––to complicate that trope. It also relates to the apple harvesting scenes, but there the focus is on the physicality, the manner and speed at which a farmworkers, Rosa, picks apples and how it is reduced to data for machine-learning.

We asked Rosa if she dreams of apples. It’s visually overwhelming and physically demanding to be in the field, after all, surrounded by rows and rows of apples. We used her answer––a much darker response about dreaming of falling off a ladder––as a way to enter a flicker "dream" sequence. This section shows an image dataset used to train the robotic picking machines. We wanted to engage the viewer’s body in the theater with its unsettling rhythm and evoke an ambiguous interiority. Whose dream are we seeing?

Can you tell me about the lines at the beginning of the film? From John Locke’s The Second Treatise of Government (1690):

He that is nourished by the acorns he picked up under an oak, or the apples he gathered from the trees in the wood, has certainly appropriated them to himself.

I ask then, when did they begin to be his?

When he digested?

Or when he ate?

Or when he brought them home?

Or when he picked them up?

This arbitrary line between what’s considered natural and non-natural has become a mechanism by which elements of the natural world can be owned. When we were looking out into the orchard, we thought, this technically doesn’t exist in nature. There’s something uncanny about that.

In the film, the apple patent was the first articulation of this idea. You can’t own an apple seed because it’s considered an organic part of nature. But if you graft an apple, if you cross a bunch of varieties and graft them onto a rootstock, then that thing can be owned because it’s an “invention.”

We came upon a Supreme Court case from 1823, a lawsuit called Johnson v McIntosh. This guy named Thomas Johnson had bought land from the Piankeshaw Tribe in the mid-1700s, and he gave the land to his children after he died. But then another guy, William McIntosh, bought the same land from Congress. The disagreement about the rightful ownership of the land was appealed until it reached the Supreme Court, who ultimately decided in favor of McIntosh, finding that the Piankeshaw did not have the right to sell the land to an individual. And the reasoning goes back to the John Locke quote, which is referenced in the Supreme Court decision. Essentially the argument is that the Native American tribes remained in a state of nature, and to leave the Native Americans in possession of land was to leave a country to wilderness. In Locke’s logic, it was only through cultivating the land, this idea of mixing your labor with the land, that one could own it instead of simply living on it.

There’s a direct and terrible resonance between the logic of the 1823 Supreme Court decision and contemporary ideas about genetics that come up later in the film, like that synthetic biology allows you to technically consider a human gene sequence to be non-natural and thereby ownable.

Mike had a realization that in a way, this is a nature movie, and all these nature movies are about the natural world disappearing through species collapse or extinction. We wanted our film to take a different tact by focusing on extraction. And ultimately we realized it’s always about adaptation… with capitalistic logic being the most highly adaptive.

It’s one of nature disappearing through privatization, not through ecological collapse.

There’s a passage in Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness on landscape painting that I thought of when I watched your film. It goes, "when nature becomes landscape—e.g. in contrast to the peasant's unconscious living within nature—the artist’s unmediated experience of the landscape presupposes a distance between the observer and the landscape. The observer stands outside the landscape, for were this not the case it would not be possible for nature to become a landscape at all."

I thought about how privatization forged this distance between us and the land, and turned nature (something we’re within) into landscape (something we regard with distance from ourselves.)

Exactly. A whole history of ownership is based on this notion that if you mix your labor with the soil, it can become something else. We realized over time that the argument presupposes the idea that the human is something separate from the natural world, otherwise nothing would be fundamentally changed through cultivation. So that mediation you’re talking about is also implicit in this proximity with the earth as well as the distance from it. That we are something other. And it’s through the logic of this otherness that we can look at something like a salamander and feel like, I want these attributes, they rightfully belong to me.

There’s mention in the film at some point about research on salamanders for the purposes of limb regrowth for war veterans––

Yes, the axolotl research on limb regeneration isn’t just funded by the National Institute of Health, but also by the Department of Defense. We were struck by how seamlessly this extraordinary, almost magical, possibility of limb regrowth gets instrumentalized. It’s like triage for the existing system. Instead of working to avoid conflict and war, the energy around the advancement is essentially to make more resilient soldiers... yeah, I don’t know if we need to say more. ♦

Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser are filmmakers working at the intersection of experimental and non-fiction film. A Common Sequence premiered at Sundance, followed by screenings at Hot Docs, BFI London, FICUNAM, and the Museum of Moving Image.

Subscribe to Broadcast