Splitting the Atom

A woman wearing a black body suit appears on a phone screen. She looks uncanny, almost cyborgian; her face is covered with a sheer augmented reality filter, like plastic film clinging onto her skin. In a fast-clipped, insouciant voice digitally-altered to sound like a sultry robot, she makes the following claim: “A long, long time ago, there was a sugar free, fat free, carbon free, all natural nuclear reactor.”

In this sixty-second TikTok video posted in June 2021, Isabelle Boemeke, also known as Isodope, explains how the Oklo uranium mine in Gabon triggered a nuclear chain reaction without human intervention, becoming the only known geological formation to naturally generate nuclear fission. The video features a blue grid backdrop where floating aliens wearing cowboy hats stand in for uranium atoms. A gold chain necklace signifies a nuclear chain reaction. Isodope revels in slapdash and irreverent internet culture to describe the wonders of nuclear energy, and it seems to be working: her Oklo video has received over 150,000 views, with some genuinely engaged commentary. (“What would happen if you built a city around the area?” one commenter asked.) In another TikTok post, she lists her skin care routine before abruptly changing the topic to debunking the common fear of radiation, visualized with rapid-fire GIFs (“Hot springs are radioactive, bananas are radioactive, even you are radioactive!”) Considered as the first “nuclear influencer,” Isodope is part of a group of young activists eager to re-introduce “nuclear” into popular vernacular, ready to defend the technology from those who dismiss it as solely dangerous.

For something indestructible, the atom has always suffered from a fragile public image, in part because of the confusing, and at times conflicting, stories people tell about its potential. One recent study found that American public perception of “nuclear” conflates atomic energy with military imagery, as a visual and emotional mishmash of science, power, contamination, explosions, and bombs. Nuclear war still looms over us like a permanent shadow; American politicians evoke the language of the Cold War in their narratives of military and economic rivalries with China. Debates about modern-day hypersonic missiles mirror past anxieties about intercontinental ballistic missiles. While advocates of nuclear energy distinguish between peaceful and military uses of the atom, they wrestle with public concern that cuts across both areas: waste. The images of accidents like Chernobyl, Church Rock, Three Mile Island, and Fukushima are seared into public memory. Shiprock, Hanford, Runit Dome, and other “legacy” sites around the world that hold waste from nuclear weapons production also erode public trust. The atom had become hopelessly entangled with the policies, images, and stories of our own making.

Isodope’s efforts to rebrand the atom is all the more remarkable when considered alongside those over half a century ago, namely Walt Disney’s famous 1957 project, Our Friend the Atom. One of its stories, Walt Disney’s retelling of the folktale The Fisherman and the Genie, begins with a mysterious jar caught between the tangled ropes of a fisherman’s empty net. Desperate for a catch, the fisherman opens the jar in hopes of finding something valuable inside. To his horror, the jar releases a trail of smoke, billowing out to form a towering mushroom cloud. In the debris emerges a sinister entity: a cursed genie. “Thou, old man, art my liberator,” the genie thundered. “And according to my solemn vow, thou must Disney remained true to the original fable: in the end, the clever fisherman manages to trap the genie back in the vessel until it promises to spare his life and bestow him wishes and wealth. But the moral of the story has been repurposed. In this version, a tale of the future, the genie is the atom, the fisherman is mankind. Their fateful encounter represents the difference between prosperous life or cruel death: can humans tame this new powerful force?

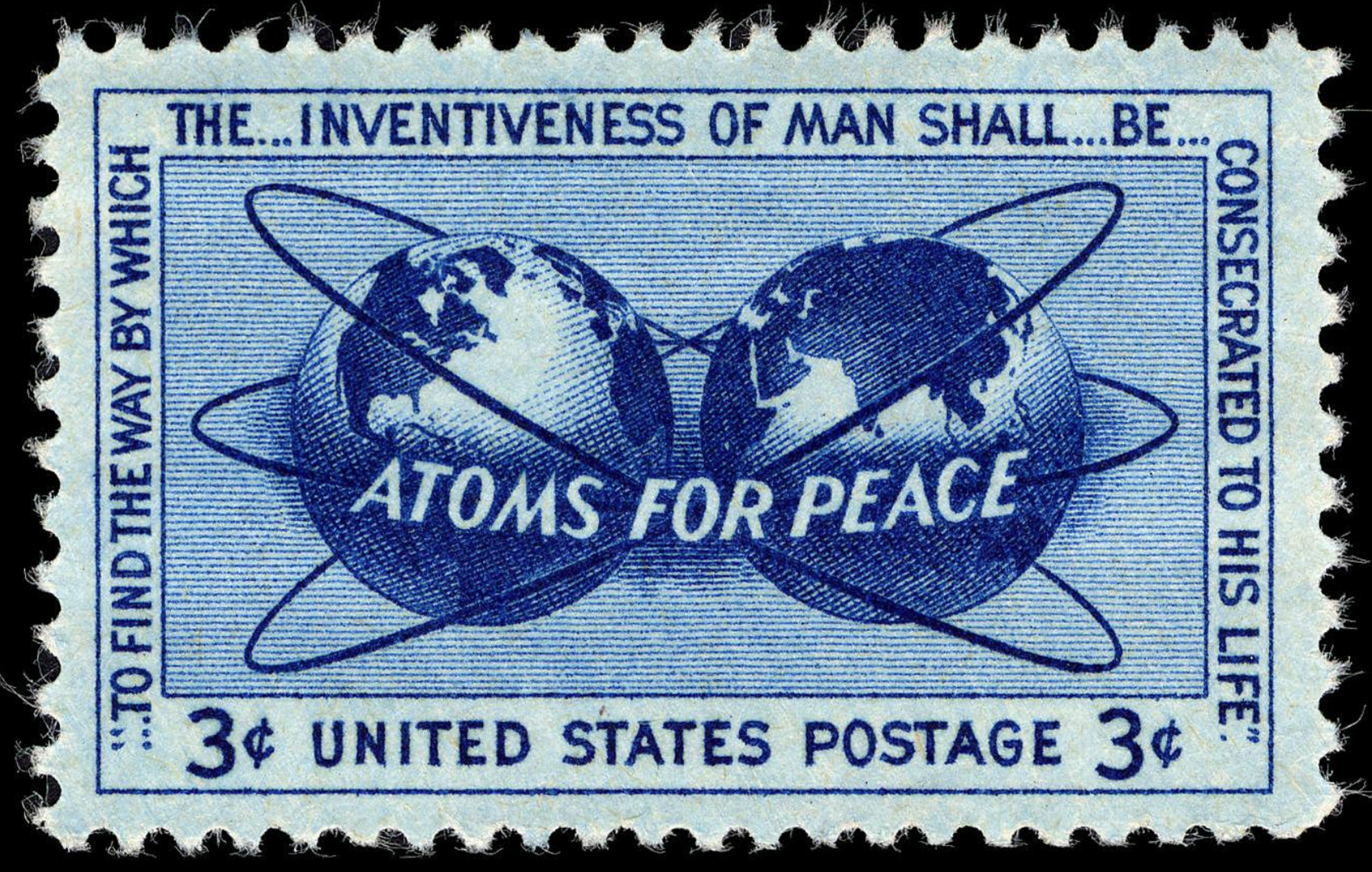

Our Friend the Atom is a thinly-veiled propaganda book and animation released to promote “positive and creative” atomic projects amid an escalating nuclear arms race. Our Friend the Atom captures Disney’s enthusiasm for nuclear science, encouraged by partnerships with the U.S. Navy, General Dynamics (the company that built the first nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Nautilus), as well as scientists like Heinz Haber, who advised American missile technology during the Cold The project followed President Eisenhower’s 1952 “Atoms for Peace” speech, the first diplomatic call to share nuclear knowledge and technology to improve the fields of medicine, agriculture, and energy around the world. A peaceful atom was a tough sell after American atomic bombs had killed hundreds of thousands in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945; besides, other nations like the Soviet Union were actively building their own weapons programs. Convinced that an amicable bond between man and atom is possible, Disney used image and plot to help popularize Eisenhower’s vision to reimagine nuclear science beyond warfare, and in turn, transmute “nuclear” into a political and ethical aesthetic.

The common visual associations of the atom fail to convey the amount of space and energy it contains. The most recognized atomic structure is based on Niels Bohr’s model—the nucleus at the center with electrons whizzing around it like planets orbiting the sun. Plastered on textbooks, coffee mugs, and Powerpoint presentations, it is often used as a generic symbol for anything scientific or futuristic. Used as an aesthetic, the atom loses its active meaning, and becomes a flat, abstract image in our minds.

So instead, we rely on stories and images to help us understand the atom. Spencer Weart, the first historian to catalog stories and images associated with nuclear phenomena, produced an archive that resembles a cabinet of curiosities: mad scientists from novels written by H.G. Wells and early sci-fi authors; radioactive monsters spawned by Studio Toho and other post-WWII Japanese cinema houses; and films ranging from Paramount News’s The Atom and You (1953) to the BBC’s Threads (1984). A common theme emerges from these disparate artifacts: humans are at the center of the story, depicted as champions or victims. In his book The Rise of Nuclear Fear, Weart describes this as a “classic confrontation between hero and monster.” Weart explains that both protagonist and antagonist narratives are compelling since “each component represents an aspect of our own At work here is the fusion of image, story, science, and politics to generate a collective myth which, as scholar Michael C. Williams argues, plays a crucial role in mobilizing political concepts among a typically disengaged polity. In Williams’s view, the public’s fear and hope during the Cold War became a “productive aesthetic dimension of power

Nuclear proponents like Disney built on this rhetorical technique. Film scholar Mark Langer observed that Our Friend the Atom characterized the pioneers of nuclear physics––from ancient Greek philosophers who first questioned the composition of matter to the scientists who discovered atomic properties––as “historical pageantry,” similar to the way Disney portrayed David Crockett, Abraham Lincoln, and other historical figures. However, Our Friend the Atom and similar “atoms for peace” initiatives could not completely escape the reality of the Cold War; it is difficult to persuade hope in the nuclear story, when this technology is actively used for committing acts of violence. By the early 1960s, scientists and physicians were using newfound knowledge on radioactive materials to develop medical diagnostics, cancer therapies, and molecular tracers that propelled environmental studies. At the same times, the nuclear weapons club would expand: France would test a nuclear bomb in the Saharan Desert, followed by China’s in the salt beds of Lop Nur. The United States’ and the Soviet Union’s tense rivalry would almost lead to nuclear exchanges, most notably the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. The rare, but horrendous, accidents in nuclear power facilities would overshadow the atom’s contributions to medicine and agriculture research. Disney’s project had failed to materialize as he envisioned it. The push and pull between experimentation and weaponization split the atom in a binary of good or bad, which would frame political and scientific debates for decades to come.

Today, new narratives about the prowess of the atom attempt to complicate this binary. Similar to Our Friend the Atom, Isodope’s TikTok intrigues audiences with striking images suited to the sensibilities of the current generation. She side-steps visual clichés and excessive scientific detail, preferring youthful, eclectic aesthetics: animated eyes and lips superimposed onto videos of nuclear power plants, or neon GIF collages paired with direct criticism of fossil fuels or wasteful fashion industries. The work calls to mind Marshall McLuhan’s premonitions about new forms of media, particularly the role of probes: when “seemingly disparate elements are imaginatively poised, put in apposition in new and unique ways, startling discoveries For Isodope, it is less essential to know the facts as a nuclear physicist would, but to come to new ways of synthesizing scientific knowledge.

Isodope challenges what she believes is an anachronistic contempt for nuclear technology. While she renounces nuclear weapons, she also points out a new imminent threat to humanity: the unchecked dependence on fossil fuels, ushering the world towards environmental collapse. As a low-carbon energy source in the form of nuclear power, the atom is not just a gateway to a promising future, but an essential means to save the future. Isodope’s stories and others like them are invitations to re-evaluate humanity’s relationship with nuclear technology, a necessary exercise for younger generations that have inherited all of its inventions, images, and stories. Yet many of them have not witnessed the atom’s potential for destruction firsthand, and might not remember that nuclear weapons are an equally serious threat today.

Atoms are made in the center of stars, and in turn, atoms make life as we know it. But over time, this infinitesimal power became flattened into overly simplistic categories of “good” and “bad.” The atom shouldn’t be understood through such a reductive binary. To tell stories that champion peaceful uses of atomic technology, including nuclear energy, will require equal effort to denounce the development and use of nuclear weapons. We will never see the atom’s true promise of prosperity, if it also continues to only remind us of death. As we generate new aesthetics that explain what the atom is and could be, we must go beyond the usual frame of dominance and control by sharing nuanced stories that seed responsibility, stewardship, and respect. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast