In the Reek of the Real

Smell isn’t like most other senses. Unlike sight or hearing, olfaction is immersive—a subliminal contact sport. The odors that pass us by every day—a blast of sea-spray issuing from a laundry room vent, a passing cloud of marijuana smoke—are actually complex, morphing masses of volatile compounds we take in through the nostrils, which our brains translate into smells. From our noses, they’re directly conveyed to the part of our brain that processes memory, which is why odors prompt such immediate responses, making us draw near or recoil. And recoil is just what I did when my nose was invaded by some syrupy, pungent molecules steaming off a garbage bin outside the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. I was there to meet the artist Sissel Tolaas, who had just opened a solo exhibition in the space. The offending odor drifted past us again just as we began our conversation, and I felt compelled to mention it. “I think it’s very interesting,” Tolaas responded with a joyful grin. “Come to me!” She proclaimed in the odor’s direction. “I embrace you. Let’s be friends.”

This moment gets to the heart of Tolaas’s three-decades-long artistic practice devoted to the world of smell. The first tenet of her practice is that “every smell has a purpose and a right to exist.” The second, that “nothing is more honest or true or real than smell.” Learning to abide by her own principles required her to rigorously retrain her senses: to slough off the emotional triggers attached to some smells (such as, for Tolaas, sour milk), and to reject the customary drive to divide smells into binaries such as dirty and clean, or foul and fragrant. “My aim was to go beyond bad or good, to just approach smell as pure information,” Tolaas explained to me. Cultivating tolerance and even a liking for initially off-putting smells, she pointed out, is a capacity that humans have intrinsically. “Like cockroaches and rats, humans are the biggest generalists on planet earth.”

This call for olfactory equanimity runs through Tolaas’s work, including the first piece that introduced me to it: Sweat Fear/Fear Sweat at the 2014 Kochi Biennale in India. In this installation, she conscripted twenty anatomophobic men—that is, men who shared a fear of bodies—and had them collect their armpit sweat after they encountered what they feared. She analyzed these sweat deposits through a gas chromatography sampler machine, and then created smell imitations, which she infused into locally sourced ballast stones. Rubbing those cool, dark stones and taking in the variously nutty, sour, and gamey fragrances that arose from them was strangely intimate and almost felt intrusive to inhale, like pressing up against a stranger in a moment of acute distress. Such an experience is not to every gallery-goer’s taste. As Bill Arning, Curator of MIT’s List Visual Arts Center (where an early iteration of Sweat Fear/Fear Sweat was displayed in 2005) observed in his essay for the exhibition catalog, it was “not uncommon for visitors to huffily refuse” to participate in Tolaas’s exhibit, “as if to accept would forever compromise their personal security.”

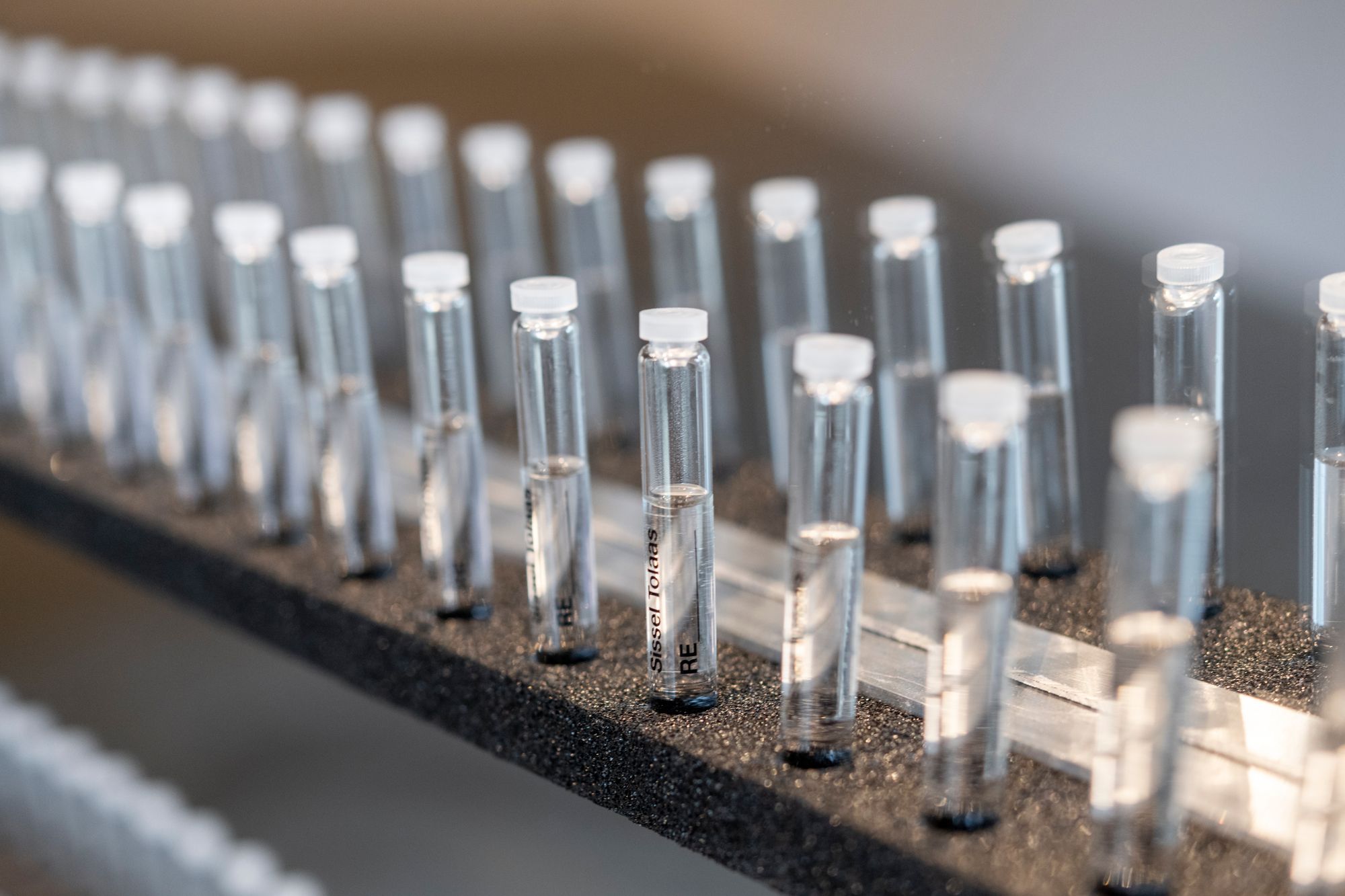

The exhibition “RE_________,” which ran at the ICA Philadelphia between September and December in 2022, gave people plenty of opportunities to take in odors that were less than inviting. Right at the entrance, visitors encountered a wall of vials—an installation titled Liquid Money—each of which, uncorked, gave off the metallic reek of nickels and dimes. (Visitors could walk away with an ampoule each.) Another installation, titled AirReBorn BelowAbove (1994-2021), featured fans containing chalky smell recordings from the North Sea, made as part of a research project with UNESCO to detect pollution through smell and pattern flow. These fans were connected to real-time sensor data on the weather off the coast of Oslo. So, when the wind blew there, the fans whirled, sending out a powdery fragrance, and making the thin periwinkle-blue curtains around them flutter. Visitors could also wash their hands with Self-Portrait, a soap Tolaas made out of her own odor. Then, there was what she referred to as the “table of empathy,” containing 250 objects embedded with smells collected from around the world, from South Korea, to China, South Africa, Australia, and the Midwest. The essence of fearful men made a reappearance, this time slathered onto a wall and a banister, their smells activated by touch. Not all the installations were intended for human consumption. One artwork, developed with the University of Pennsylvania’s veterinary school, could only be experienced by dogs. A compound smell, developed to train rescue or sniffer dogs, was daubed onto the walls at a canine-friendly height. (Some accompanying humans did kneel down to take a futile whiff.)

Tolaas’s fondness for sensorial provocations puts her work in conversation with practitioners in the burgeoning field of bio-art, many of whom are her collaborators. They include the microbiologist Christina Agapakis, with whom Tolaas once produced cheeses cultured from skin-dwelling microbes. It also includes Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, one of whose recent artworks featured a dawn chorus in which birdsong was gradually supplanted by synthetic machine-learned calls. Ginsberg, Agapakis, and Tolaas have worked on a project that attempted to reconjure the smells of extinct plant species lost to colonial extraction. All of them are adept at what ICA curator Zoe Ryan calls “ambidextrous thinking,” which straddles the worlds of the laboratory and the art gallery. They are also driven by a similar purpose: using technology to draw attention to complex webs of interrelatedness in an age of mass extinction.

As weighty as many of these issues are, Tolaas explores them with an anarchic, Dadaist spirit, and a penchant for playful, body-first experimentation. She has coined her own lexicon—nasalo—which supplies more precise, neutral terms for smells. These range from FRE, to refer to a “a wet and rainy street after a sunny day,” to P’ULCHA for “dog,” and WOO for “timber.” “I have two wardrobes, a wardrobe of garments and a wardrobe of smells,” she told me. “If I want attention, I wear molecules that amplify my own smell. But I also have molecules that make dogs come after me. Or bees.” Her preferred party trick makes good use of this olfactory armamentarium. She likes getting dressed in cocktail attire—Tolaas strikes an impressive figure, with her angular blond bob and icy blue eyes—and dabbing on molecules that evoke something incongruous, like the goaty reek of a footballers’ locker room. “Sometimes I go to a party, don’t say a word, and just stand around looking at people totally upset about some smell invading the space,” she told me. “No one would ever think it came from me because I don’t look like I smell like that. I love that kind of organic confusion, you know? The number one subject of small talk in the world is the weather. When I’m around, that changes.”

It was, in fact, small talk about the weather that inspired Tolaas’s earliest forays into the world of smells, when she was “a nerdy child” growing up on the coasts of Norway and Iceland. “I was provoked by the fact that people just spoke of good and bad weather, despite there being so many different types of rain, snow, and wind.” As a teenager, she carried out experiments in the kitchen and the laboratory, “forcing chemicals together” in beakers to produce micro-weather situations, like a little explosion that approximated a thunder clap. Very often, her micro-weather systems left behind a lingering odor. It then occurred to her that, like weather, smell was a sense that “had a kind of invisibility perception” that eluded language.

Installation view, AirREborn, Sissel Tolaas, "RE________”, ICA Philadelphia, 2022.

Photo: Constance Mensh.

Installation view, D_earth, Sissel Tolaas, "RE________”, ICA Philadelphia, 2022.

Photo: Constance Mensh.

Installation view, Liquid Money_ (Ampoules), Sissel Tolaas, "RE________”, ICA Philadelphia, 2022.

Photo: Constance Mensh.These experiments led Tolaas to study chemistry, mathematics, linguistics, and fine art in a number of institutions and art academies in Bergen, Warsaw, Poznan, Oslo, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. Shortly after, she moved to Berlin, where she decided to investigate the under-explored world of smells, and to hone her olfactory skills. Between 1990 and 1997, she traveled around the world, gathering a diverse archive of 6,733 “non-obvious” smells from a variety of sources—everything from dried fish and rotten bananas to grimy cloth––and archiving them in cans. This research, as she put it, entailed “putting my nose first, literally. Exploring the world through my nose. To let the smell do the talking.” Sometimes, smells spoke in a whisper, which invariably led to a dogged hunt of their elusive trail. “I always made an effort to find the source of the smell, and it sometimes would lead me to the façade behind a courtyard. Like a combination of a hound and an archeologist.” Using her nose and simple tools, she investigated the life cycle of a smell—how long it lingered, and how swiftly it decayed.

Pursuing smells in the intensive way that Tolaas does would not be possible without the cooperation of the industries that dominate the realm of smell and taste. From the early 2000s onwards, her work has been supported by industrial behemoths that create the high-end fragrances and tub-scrubbing liquids that blitz into oblivion the sorts of real and complex smells she likes befriending. These include the Paris-based Quest and the New York-headquartered International Flavors and Fragrances, the latter of which helped her build her research studio in Berlin. By working with their research and development teams, psychologists and chemists, she was able to gain access to devices and proprietary technology that would otherwise be inaccessible to most artists. She found out how exactly these corporations synthesized the smell of a rose, and learned to use headspace technology, a technique developed in the ’80s that isolates and decodes odoriferous molecules found in the air, enabling a sort of smell snapshot. “What I tried to accomplish was to use the same knowledge [they controlled] to reveal what is going on before they come and cover it up,” she told me. “It’s about understanding the invisible part of the world. Otherwise, we’re letting marketing take over where science leaves.”

The fragrance industry titans—and headspace technology’s inventor—were, according to Tolaas, curious about her unorthodox approach. The inventor, Braja Mookherjee, in fact, contacted Tolaas to help develop technology that caters to her specific research needs. From then on, she began to carry with her a mobile odor recorder to document and analyze smellscapes everywhere she went. She has since amassed as many as ten thousand molecules and compounds, some of which have since been banned by regulators—whom she calls the “molecule police”—in the EU. The collection is driven by Tolaas’s determination to resist her industry patrons’ drive for deodorization, which produces, she thinks, a reflexive intolerance, an indifference to local particularity, and worse, an incuriosity about the histories, cultures, and contexts of so many smells. She uses the industry’s tools to resist the “blandscapes” their deodorizing brings into being: placeless places whose floors are all redolent of the synthetic smells of Granny Smith Apple™. To walk through her show was to encounter, through my nose, evocations of fleeting life-worlds. After three pandemic years of understimulation, I smelled my way through the installations, noticing the many feelings and memories they dislodged, thinking of Tolaas’s words: “A smell is an artifact of life,” she reminds us. “It’s not abstract nothingness; it comes from a source.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast