Actual Presence

Watch selected films from Michael and Christian Blackwood here.

Cinéma vérité is simultaneously one of film’s least helpful categories and a sign that you are close to the gold. Developed as an idea in the late ’50s by filmmakers like Jean Rouch, vérité (or “direct cinema”) was thought of as a kind of pulling back on the director’s part, a way of foregrounding that which was being filmed instead of the person with the camera. Voiceover is a no-no in vérité—the creator and the audience member are both thought of as flies on the wall, eavesdropping on life as it unfolds. In 1967, in the Journal of the University Film Producers Association, filmmaker Hubert Smith wrote that cinéma vérité ideally “minimizes the limitations that film imposes in transferring reality.” Smith went on to write that vérité “gets as close as possible to the visual, aural, and kinesthetic sense of actual presence” (italics mine). The work of American filmmakers like Frederick Wiseman, Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, and the Maysles Brothers foregrounds that presence as much as possible. If you know just one of their movies, you’re well on your way to understanding vérité.

Drew said in an early TV interview that this new movement, aided by the development of portable cameras with sync sound, enabled filmmakers to get away from the “word logic” of the documentary form, which felt to him like “lectures.” It was time to let the subject speak, so to speak. Drew’s documentary about the 1960 Wisconsin primary, called Primary, was one of the first vérité documentaries: no voiceover, no intermediary between the viewer and what had been filmed. The relationship of the subject and the director was drastically revised by the practice of cinéma vérité, a way of adjusting the balance of power between these two figures. When the director’s presence is limited to framing and editing, that being filmed can take over. But the director is still making the decisions about the frame, no matter what happens inside the frame. There is no documentary in which a subject spontaneously films all by themselves for ninety unbroken minutes (though social media and livestreaming bring us closer to that singularity). What seems like a genuine break from other forms is long, unbroken segments of sync sound film, free from voiceover. If you watch someone perform a task for a solid minute or two without commentary—something rarely seen in a feature film or a traditional documentary—a presence will emerge, and that authority is something no editor can easily supersede.

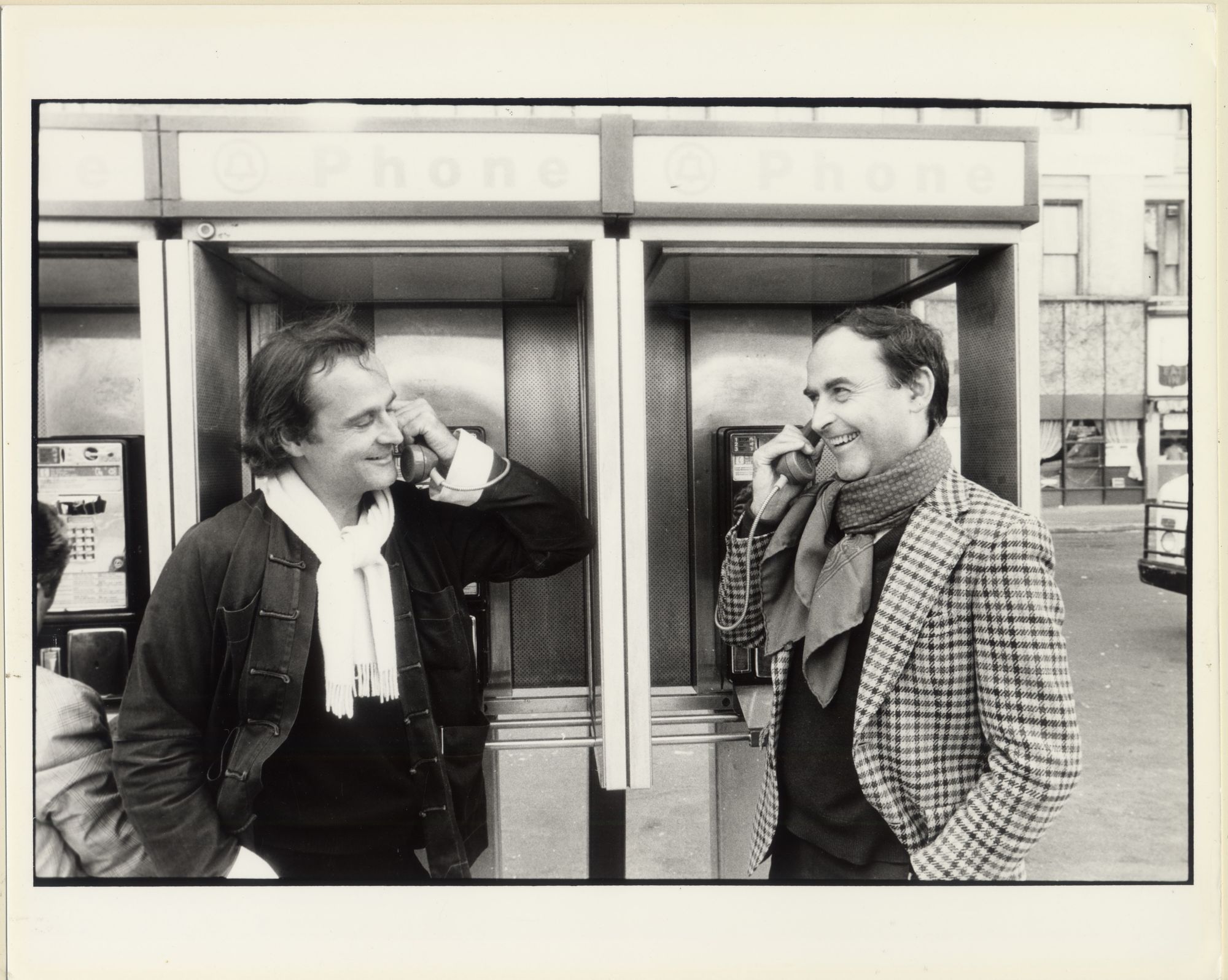

A long attention span and respect for the subject are at the heart of the documentaries Michael and Christian Blackwood made over the last sixty years. Time and time again, they manage to get out of their own way, beautifully. The brothers began working together in and around news television, and made important records of mid-century New York. In the subsequent decades, Michael made a series of essential films about artists and architects that I’ve been returning to for just as long.

Michael and Christian Schwarzwald came to New York from Germany in 1949, when Michael was fifteen and his brother only seven. In Berlin, their parents ran a textile business that made costumes for theater productions. “The director would come and discuss needs with my parents,” Michael told me a few summers ago. (Christian died in 1992.) “My grandfather had a company that sold textiles to department stores. My father was a salesman, and he changed what the business did.” Once in New York, Blackwood went to George Washington High School and sold Fuller Brushes. “After high school I soon decided to become a documentary filmmaker and was apprenticed to Isaac Kleinerman, a first-rate film editor at the time,” Blackwood wrote in a 1994 essay. “By 1957 I was making my own films, the first being a portrait of the New York subways at night, titled Broadway Express.”

Broadway Express is a twenty-minute silent film set to an original jazz score by Howard Gilbert. Riders on the A train sleep, jostle, and argue, all without the framing of narration or subtitles. They simply exist, and we have to pay close attention to them in the absence of outside explanation. Seen sixty-odd years later, it feels like an actual time capsule, lives being lived without being reduced.

In 1961, Michael and his brother went back to Munich and worked for West German television until 1965. Upon returning to New York, Michael and Christian began an astonishing run as documentary filmmakers, working together often, though not always. The films that they are best known for, by a wide margin, have an unusual history within any branch of documentary. Still working with West German television, the Blackwood brothers produced two-hour-long films about Thelonious Monk in 1968—Monk and Monk In Europe, the former shot in New York. These became widely known, because twenty years later, Christian made a deal with director Charlotte Zwerin, who built her Straight, No Chaser Monk film largely from the footage shot by the Blackwoods.

Zwerin’s film brought Monk to the masses, but it’s the Blackwood movies I return to. This is straight vérité, with absolutely no narration or text outside the events in the frame. Nobody is calling Monk “eccentric” when he turns around in circles, more than once. You don’t know that Monk and his band are at the Village Vanguard or at Sony Studios with Teo Macero—you have to absorb what Monk is doing and how he is playing, guessing at his moods. The film quality is dense, shades of black and silver. The actual presence of Monk and his collaborators sinks into your consciousness.

The brothers stopped collaborating in the early ’80s, and Michael leaned into what became his legacy: the ways of artists. This pursuit began early, in 1969, with Christo and Wrapped Coast. Have you ever wondered what it looked like when Christo clambered all over the rocks in Australia and dragged tarps across them? Or how the onlookers were reacting, long before Christo was a celebrity? The physicality of a practice that often seems entirely conceptual is not a minor piece of reporting.

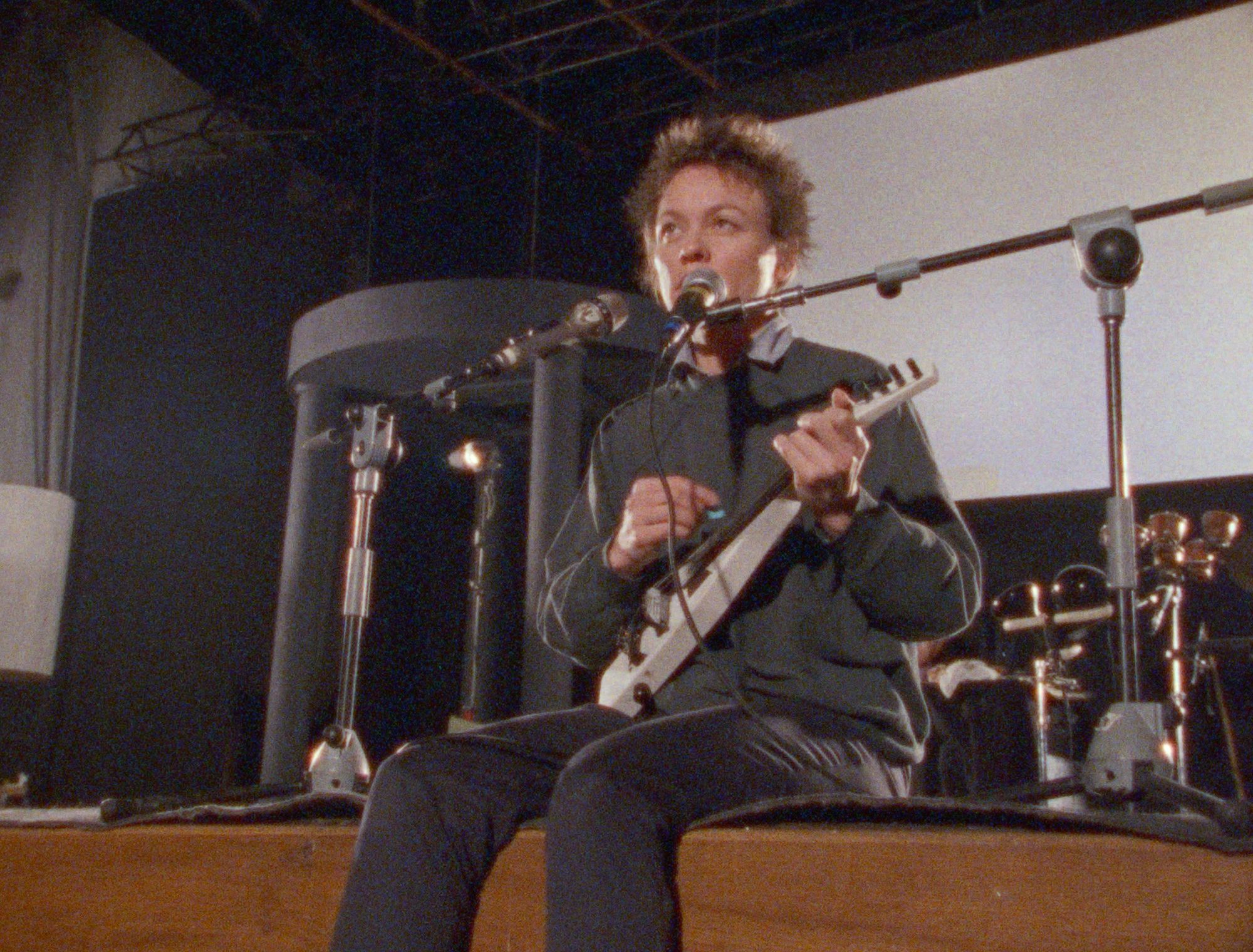

Laurie Anderson. Michael Blackwood, The Sensual Nature of Sound, 1993, 58 mins, color.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Pauline Oliveros. Michael Blackwood, The Sensual Nature of Sound, 1993, 58 mins, color.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Talia Leon. Michael Blackwood, The Sensual Nature of Sound, 1993, 58 mins, color.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Talia Leon. Michael Blackwood, The Sensual Nature of Sound, 1993, 58 mins, color.

Photo courtesy of the artist.Philip Guston: A Life Lived, from 1981, is a modest masterpiece, partly because of how openly and easily Guston talks. I love watching Guston paint (I like watching pretty much anyone paint, as it’s such a distinct piece of information, a gesture you can't fake or take back) and he narrates his life, talking about the New York School (he likes the term) and meeting DeKooning at the WPA projects. He talks about Rothko and Motherwell, and how “we all electrified each other.” In Robert Motherwell: Summer 1971, Motherwell paints the 114th (he thinks) in his Spanish Civil War Elegy series, cigarette dangling, calmly applying the black as if he’s redoing the bathroom.

The thread that ties together so much of Blackwood’s work is a sense of patience and respect, so that even when the documentary form includes narration, it usually comes from the painters and musicians themselves. For as many times as some magazine runs a “women in music” feature, there are very few films as valuable as Blackwood’s The Sensual Nature of Sound, which documents and interviews Laurie Anderson, Meredith Monk, Pauline Oliveros, and Tania León. There are very few films that give as much unbroken time to these artists, to let them simply talk.

My favorite might be The Artist’s Studio: Jean Dubuffet, most of which was filmed in 1973, as Dubuffet prepares for a theater piece and builds a model for a large public plaza. Long, long stretches of the movies, minute after minute, are devoted to Dubuffet carefully clipping shapes from paper, or cutting larger shapes out of sheet metal, or carving three-dimensional forms in styrofoam, silent except for the rustle of the material under the knife, falling from his hands to the floor. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast