Learning to Listen with Annea Lockwood

I’ve made many documentary films over the years, and each one has changed me in some way, but none as much as the film I just recently finished called 32 Sounds. The film weaves together 32 different recordings as well as images, music by JD Samson, and voice-over to create a meditation on sound. Or put a different way, the film uses sound to consider some of the basic features of our experience of being alive: time and time passing, loss, memory, connection with others, and the ephemeral beauty of the present moment.

The 32 sounds range from the foghorns of San Francisco to a recording of the womb made by Aggie Murch (whose husband is the great film editor Walter Murch), and from the sound of Philip Glass playing the piano to a recording of a man playing trumpet while bombs fall all around him in Beirut. Throughout the process of making this film, and even today, I marvel at how tuning into the sounds all around us can root us in the present moment and connect us to the world outside in profound ways.

Which brings me to one of the inspirations for 32 Sounds: very early in the pandemic, I was reading a book about the great composer Pauline Oliveros, and came across a reference to a lifelong friend of hers and a fellow composer, named Annea Lockwood. The book mentioned that Annea Lockwood had been recording the sounds of rivers for more than 50 years, and that intrigued me.

I poked around online and learned that Annea Lockwood was born in 1939 in New Zealand. She was musical and studied classical piano as a young person. But then in the early '60s, she moved to Europe and fell in with early avant-garde music circles. She studied with an electronic music pioneer named Gottfried Michael Koenig, where she attended Darmstadt (the German music festival that was a kind of mecca for the radical wing of the classical music world at that time) and crossed paths with John Cage.

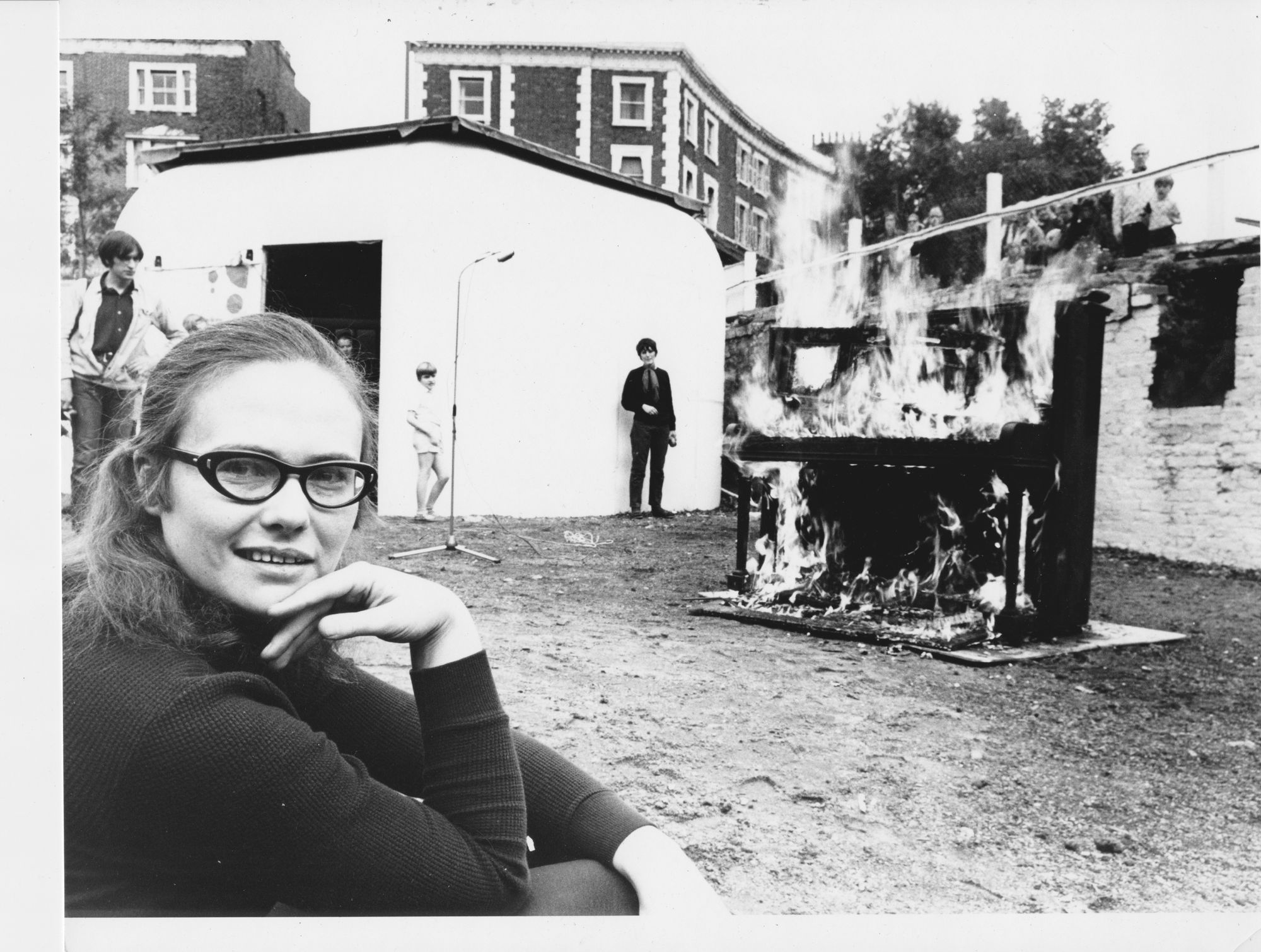

Her work was all over the place (in the best sense of the word), from early electronic collage-y pieces, to a body of music made with glass, to performative works such as Piano Burning (basically lighting an old piano on fire and calling it music), to the long-running project of recording rivers, which has resulted in a series of albums based on specific waterways.

This being the spring of 2020, everyone was stuck at home. I emailed Annea Lockwood out of the blue and asked if she’d be up for talking with me on Skype. She said sure and we struck up a wonderful ongoing conversation and friendship.

(This is a bit of an odd essay, in that I’m wondering if at certain points you might be up for listening to some audio while you read, which I think will open up what I’m saying in nice ways. If you are, hit play on this audio file below. It’s an eight minute excerpt from Annea Lockwood’s 2005 record A Sound Map of the Danube. And it will be much better if you are wearing headphones! Feel free to take some breaks to listen.)

Annea Lockwood was a great pandemic muse. I was in Austin, Texas, and she was in Crompond, New York. Our conversation continued through the summer and fall of 2020. (Even writing that, I find myself feeling a swell of early pandemic nostalgia.) Stuck at home, I learned as much as I could about her, doing the kind of deep research one can do with Google these days (transcripts of long oral history interviews from Yale, etc.). I also wrote emails a couple of times a week asking about this or that obscure moment in her career. We Skyped sometimes. She was gracious and game for it all.

As I worked, I often played Annea’s music. There was one song that just mesmerized me. And I noticed that my three-year-old son, who was often around my desk because this was early COVID and we were all at home, seemed to love it, too. I chalked this up to the song having some odd magic, which it really does.

Annea made “Tiger Balm” in 1970. The song fits roughly in the category of “tape music” or “collage” or “musique concrete.” It’s a series of non-musical sounds (a cat purring, a plane passing overhead, a person having an orgasm) combined with some melodic elements, and the effect is absolutely spell-binding—or at least it is for me (and apparently my three-year-old son as well). It’s a long song—it very slowly unfolds. (I’d encourage you to give yourself at least five minutes to be drawn in, in fact, so I won’t be mad if you take a little break from reading to do so.)

One of the questions I asked myself often in doing research on Annea Lockwood was “why had I never heard of her?” And many people who see my film ask the same thing. She has been making important work, and work that is critically acclaimed, for more than 50 years. She’s a treasure and a piece of living history. She should be as well known as Terry Riley or John Cage or Pauline Oliveros.

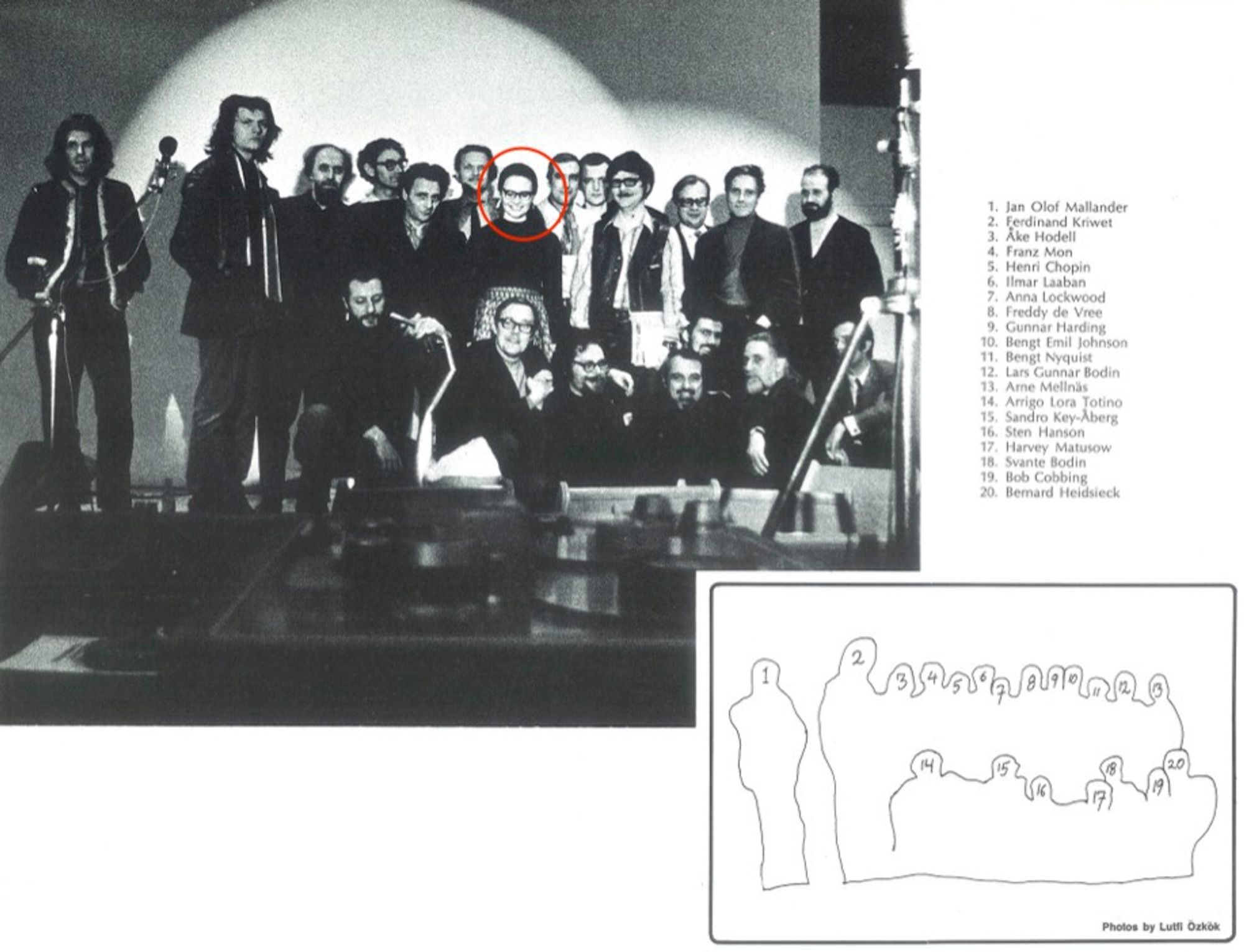

Obviously, some of this is just sexism. There’s a famous photo of a kind of who’s-who of avant-garde composers from Source magazine in the late '60s, and it’s 25 dudes and Annea. It says a lot.

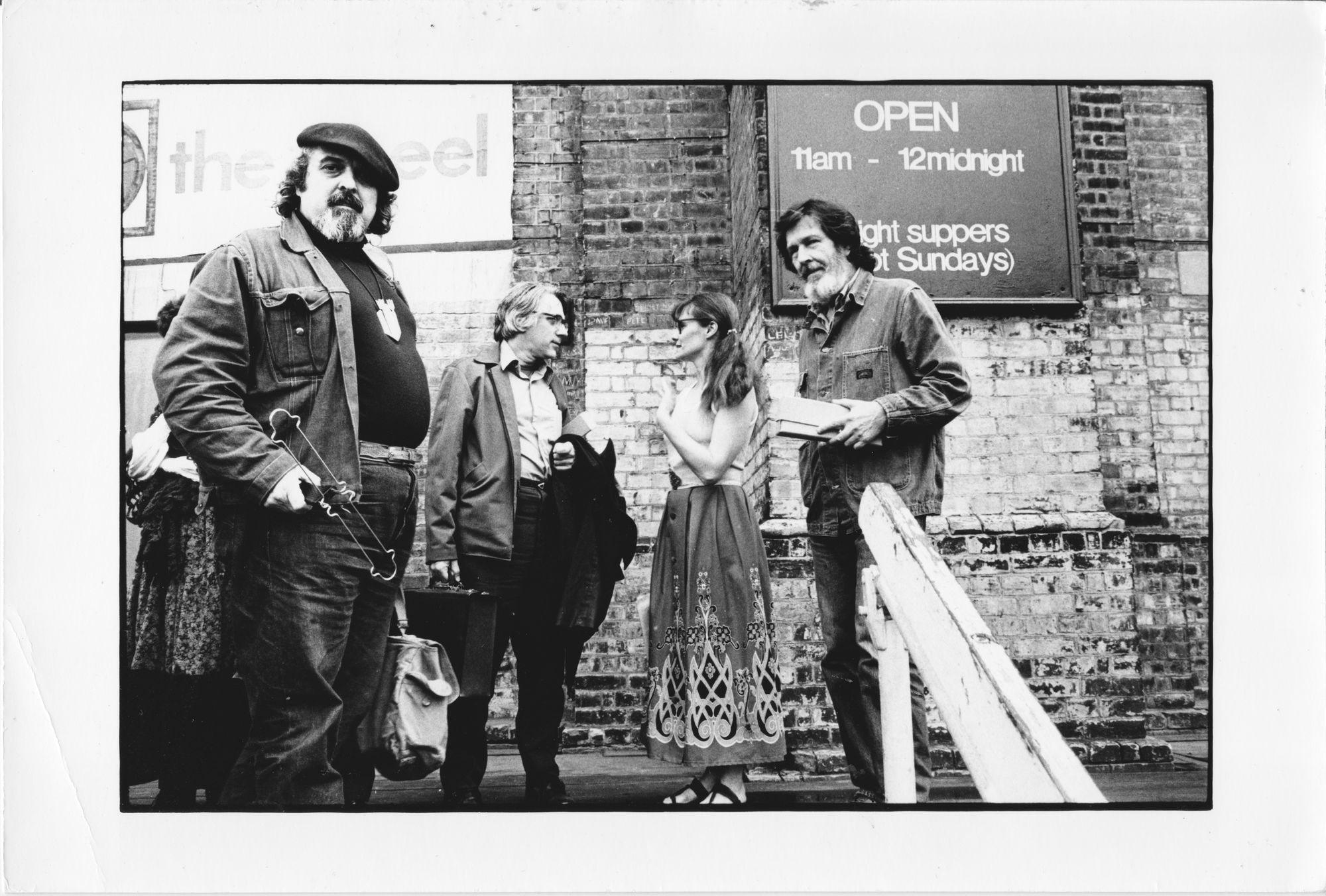

But sexism seemed like only part of the story. At some point, Annea sent me a bunch of old photos, and I was especially struck by one image of her with John Cage (below), taken in London during the ICES Festival in 1972, which was kind of the Woodstock of the musical avant-garde.

It may be just a coincidence, but I couldn’t help but notice the way that Cage seems aware of the camera, with his usual air of self-satisfaction, and Annea is completely unaware, facing left and talking with David Tudor so you don’t get a good sense of her. And this photo too seems apropos to me. John Cage was a brilliant artist and a huge genius, but he was also a consummate mover and shaker. And Annea Lockwood is not.

I’m not trying to romanticize someone who is bad at schmoozing here. I just think Annea has always been a grounded person who does her work without an all-consuming need for attention. And that’s one of the things I really admire about her. In the early 1970s, she fell in love with a composer named Ruth Anderson and they bought a little house in Crompond, a small town about an hour north of New York City. She’s always had this quiet base from which to work. She is a genuinely sweet person, seemingly without any of the trauma and grudges and accumulated bruises that many older artists have.

During one of my many pandemic conversations with Annea, I asked her what music she was listening to, and she said that she wasn’t listening to music at all. She explained that Ruth Anderson had died a few months earlier, and music stirred up too many feelings. She said that she had recently come across an old cassette tape, put it in a player to see what it was, and a song called “Graceful Ghost Rag” came out—it had been one of their favorite songs many years ago and “it's absolutely beautiful, the harmonies are gorgeous, subtle, and lovely. It just knocked me out, I hadn't heard it for years. Whoops!”

Instead of listening to music, Annea said that she was going out on the deck behind her little house in Crompond every night at dusk, and listening to the sound of the world—the crickets and birds and distant traffic and dogs barking. That this was soothing to her. She went on to describe this as part of something she calls “listening with.” It might seem a bit hippy-dippy, but I was profoundly moved by the concept coming from her:

There's something I started writing about, about a year ago, listening 'with' as opposed to listening 'to.' And it's my sense that if I'm standing here, I'm just one of many organisms that are listening with one another within this environment. Not even to the environment, we're within it, and we're all listening together, as it were. I think of sound as being an energy channel from one phenomenon to another, a sensory channel of connection that's very strong and shows me how deeply connected we are with everything else that's around us.

Occasionally in my life I’ve come across an idea, or a book, or had a conversation that’s changed me, and hearing Annea talk about “listening with” was one of those moments. I think of sound in a fundamentally different way now. And I now take great pleasure and comfort in opening my ears from time to time and paying close attention to the sounds around me. I often think of Annea in these moments, and sometimes even whip out my phone and record a quick voice memo to send to her as a text—like this recording I made of church bells in Venice in the spring:

“For those 5 minutes I was truly somewhere else,” she wrote back. “It was lovely—such a cloud of resonances/pitches around the main tones—sort of shimmering. Thank you!”

In one of our conversations, Annea offhandedly described herself as a ‘lucky person,’ and I was taken aback. I don’t know if I’ve ever met someone who describes themselves that way. (She’s definitely not Jewish!) But it’s wonderful, and this sunny-ness is part of what drew me to her. She became the glue, really, that held my ideas together while I made 32 Sounds—and it was a no-brainer, really, to also make a short companion film just about Annea, while I was at it (watch at the end of this essay).

And the world is now coming around. At a moment when people are looking critically at the history of classical music and who has been raised up over the years, Annea Lockwood is being discovered. Or rediscovered? There was a big spread on her in the New York Times a few years ago. She was recently elected to the Academy of Arts and Letters. Her schedule is packed these days with international travel—projects, concerts, speaking engagements. I said to her at some point, “Annea, are you having a moment?” And she paused to think about it and then said “Well, I’ve never been asked to talk as much as I am now,” and then let out one of her signature big laughs. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast