Outgrowing God: Richard Dawkins in Conversation

The Nobel Prize winning physicist Leon Lederman wanted to title his 1993 book The Goddamn Particle as an expression of frustration that the elusive Higgs particle had still managed to evade detection. His publisher objected, fearing a public backlash. The no-nonsense scientist was eventually coaxed to agree to the epically misleading variation, The God Particle. Lederman relays that upon the book’s publication they managed to offend two groups: Those that believed in God, and those that didn’t. He adds, they were warmly received by those in the middle.

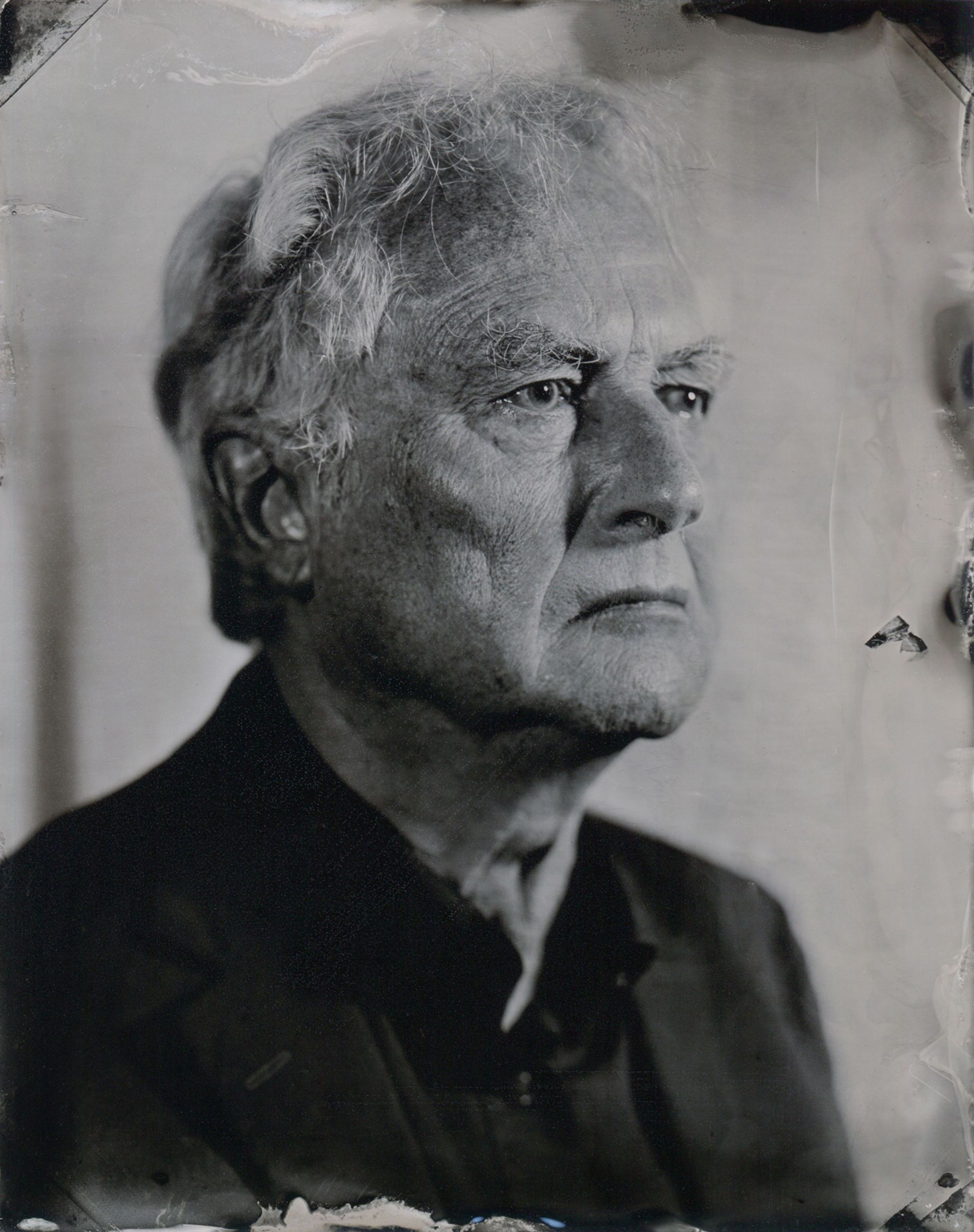

Not since Richard Dawkins’s 1976 nonfiction classic The Selfish Gene has a title been so misunderstood. At times Dawkins expresses regret that he didn’t call the book The Immortal Gene. But then, Dawkins has a great deal of experience being misunderstood. A masterful, prolific writer, he is a champion of evolutionary biology and ethology. He is also a champion of reason, a proponent that humanism and rational thinking can improve the human condition and transcend cultures, ideologies, warring factions, and nationalism. An unwavering extension of that faith in reason—pun intended—is his atheism, which he espouses in his conscientious and provocative prose, as in the simultaneously famous and infamous book, The God Delusion.

In a conversation at Pioneer Works in 2019, Dawkins recounts his own transition to atheism. As a child, he had some vague, cursory relationship to the Church of England. Ironically, he felt certain that the elaborate ecosystem of living things, so impossibly beautiful and unfathomably complex, must have had a designer. The theory of evolution changed his mind. Even more compelling than a god was the premise that the intricately layered and interwoven glory of life arose naturally.

Our conversation, which you can watch in full above, coincided with the publication of his latest book Outgrowing God: A Beginner’s Guide, in which Dawkins provides an accessible primer for young atheists—the kind of book he could have consulted during his own conversion.

Dawkins, like Leon Lederman, also manages to offend two groups: those that believe in God and those that don’t...but do believe that religion deserves a privileged, uncritical respect. (Dawkins reminds us of the bumper sticker "Blasphemy is a victimless crime.") He also seems to be warmly received by those in the middle.

Extreme adherents in the first camp have taken to writing Dawkins fraught missives, alternatively referred to sardonically as “love letters” or “fan mail.” We asked Richard to read aloud some of the most outrageous invective-laden letters. The deranged dispatches are absolutely hilarious, as any basic theory of humor would explain: humor is always at someone’s expense, in this case Dawkins’s. (Although, a few sober viewers did not find the readings in the least bit funny. Warning label: they are deeply offensive.) Here he is at Pioneer Works sharing some of the most vicious submissions:

It is unfair to implicate all believers with the pathologies of these extremists, who clearly exhibit values that are antithetical to any true adherent to Jesus. There are thoughtful theists and Gnostics who are interested in debate and open to subtle, sometimes painful, intellectual combat with the unwavering atheism Dawkins advocates. The internet abounds with such exchanges featuring the neo-atheists most vocally represented by the “Four Horsemen”: Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens. Truth be told, the rhetorical skills of the Horseman are daunting. Love or loathe them, these are the most cogent, spectacular, rousing orators of our times. When the Hitch was still with us, Richard gave the emphatic advice, “If you are a religious apologist and you are invited to debate Christopher Hitchens … decline!”

More surprising perhaps is the second offended group: those that don’t believe in God but share with the first group a conviction of moral certitude, a sense that their beliefs are so objectively righteous that there is no room for debate. They also resort to invective in lieu of thoughtful arguments and demand an end to the conversation, although I imagine their letters to be significantly less hilarious. They are reasonable, often well intentioned. But they threaten not just the antagonist—in this case, Dawkins again. They threaten anyone who chooses to listen, as though even observing the exchange of opposing views is sinful.

Maybe Richard’s own unwavering certitude inflames his fiercest critics on both sides. When accused of fanaticism, Richard says in The God Delusion, “No, please, it is all too easy to mistake passion that can change its mind for fundamentalism, which never will.” The scientific disposition is to engage with those you respect but with whom you disagree, to be open to the exchange of ideas, even uncomfortable ideas, to suffer challenges to your most foundational thinking.

Dawkins relays a pivotal experience as a young student at Oxford. An elder statesman of the Zoology Department had maintained for years a conviction that a certain microscopic feature of the cell known as the Golgi Apparatus was an illusion. Emphatically, he taught this principle to generations of students. As was customary in this class, visiting lecturers were invited weekly to present new work. On one occasion a scholar from the U.S. delivered his testimony to the contrary with compelling evidence that the feature in the cell was in fact real. Dawkins recounts, “The old man strode to the front of the hall, shook the American by the hand and said—with passion—‘My dear fellow, I wish to thank you. I have been wrong these fifteen years.’ We clapped our hands red...The memory of the incident I have described still brings a lump to my throat."

I admire Richard most as an advocate for science. I implore anyone who has not done so to read the masterpiece that is his chapter "A Garden Inclosed" in Climbing Mount Improbable. Forgive that I cannot do the tale justice in the following brief summary: Dawkins tells a gripping story set in the dark, glorious cave of a particular species of fig. The heroine is a wasp, driven by instinct to leave her home fig where all the males in the colony will spend their entire lives in darkness. When ready to lay her eggs, she flies for the first time into the light of day, never to return, ripping her wings off on entry to her new chosen home fig where her progeny will be born—only one of which, the next queen, will ever leave. She will never need her wings again and will never re-emerge. Devastatingly, the end scene concludes in the beginning. The entire drama will play out again. And again.

The fig and the wasp demonstrate what Dawkins describes as the magnificence of a world without God. Therein lies the way to transcend social boundaries, to shift our perceptions of the world, and thereby to shift our perceptions of each other.

These purely scientific dramas strike me as more compelling than any prosthelytizing for neo-atheism. But I’m not in the closet about my lack of religiosity either. When Dawkins’s publisher asked me for a blurb for Outgrowing God, I relayed this story:

My son came home from his first day in the fourth grade with arms outstretched plaintively demanding to know, practically shouting: “Have you ever heard of Jesus?!”

We burst out laughing. Maybe not our finest parenting moment, given that he was genuinely distraught. Stricken by the hilarity of the impassioned entrance, we had to reflect the same question back at him, “Haveyou never heard of Jesus?!” Had he been insulated from religion so thoroughly that the most famous figure in Western culture was new to him? He woke up one day to a world in which his peers were expressing beliefs he found frighteningly unreasonable. He began devouring books on atheism, books that helped him formulate his own arguments and helped him stand his ground. The book Outgrowing God is special in the terrain of atheists’ pleas for humanism and rationalism precisely because it speaks to those most vulnerable to the coercive tactics of religion. As Dawkins himself says in the dedication, this book is for “all young people when they’re old enough to decide for themselves.” It is also, I must add, for their parents.

A family friend, a believer, was mortified by this story, mortified that I had not taught my son about Jesus. Another friend, a nonbeliever, was scandalized that I had extended any invitation to Richard Dawkins, citing his brash tweets, not his magnificent books. I guess I also offended two groups. Sometimes, you just have to be grateful to be warmly received by those in the middle.

Stay up-to-date on new videos from the Science Studios: Subscribe to our YouTube channel

Subscribe to Broadcast