Close Encounters in the Fourth Dimension

At some lost moment in the Pleistocene, over 200,000 years ago, early Homo sapiens wandered into western Eurasia for the first time. The world they found there was largely the realm of non-human animals. As they edged northwest into the great steppe-tundra, they came across species they had never seen in Africa. Plants were no longer grazed by gazelles but by reindeer; the bloodstained muzzles snarling at them no longer belonged to cheetahs, but to cave lions. Yet there was another, much more uncanny presence in these strange parts. Somewhere along their path, these pioneers would meet alternate versions of themselves: human, yes, but of another species altogether. Soon they would get to know the Neanderthals, and this relationship would forever change the course of both species.

Maybe they first stumbled on their artifacts. Imagine it like this: a group of early Homo sapiens round a cliff and see a cave open up before them like a great dark eye. Inside, as their vision adjusts to the gloom, among moss and dust and owl pellets, they find stone tools. These objects are recognizable to them, yet nonetheless strange, made in ways that are not their own. They creep farther in, exploring tunnels and chambers. Deep in the guts of the mountain, the dancing light of their pine torches illuminates a glittering film of translucent calcite, revealing something else almost familiar. Bones, but not those of cave bear or hyaena. Instead, a skull with a human-like face, though longer and with deeper eye sockets.

Of course, perhaps this first contact was truly face-to-face, eye-to-eye—staring right into the original uncanny valley.

What’s incontrovertible at this point—though it was deemed near-science-fiction not more than a decade ago—is that among the encounters that eventually took place in the flesh, some were of a decidedly carnal nature. Numerous studies of ancient DNA prove that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were having sex with each other; indeed, this happened quite a bit. The genetic inheritance of that interbreeding, which began over 200 millennia ago, survives today: up to 2% of all living people’s genomes are Neanderthal.

The context of these relations is harder to discern. Were they care-free flings born of curiosity, long-term relationships, or were they chance assaults, part of a wider pattern of subjugation? Perhaps alternating between all three, this interbreeding persisted until around 40,000 years ago. And only a few centuries after it stopped, the Neanderthals vanished altogether, leaving behind only hybrid babies and their descendants.

And then we forgot all about them. It took until the nineteenth century, amidst seismic scientific, social, and economic change, for European industrial-military infrastructure to blast Neanderthals back into the light. We rediscovered them piecemeal, puzzling out faces and minds from dry bones and cold stones, eventually recognizing them as another sort of human. Neanderthals would become a foil for our desires, dreams, and demons. They inspired new conceptions, expectations, and imaginings about humanity in a way that is strikingly similar to emerging ideas about alien life. This connection might at first seem like a stretch, but offers many instructive commonalities. The discovery of Neanderthals and the search for beings from other worlds each challenged parochial perspectives on time, language, technology and culture—the very tenets of what had long been believed to set humanity apart from the rest of life as we know it.

Immediately following their rediscovery over 160 years ago, Neanderthals started exerting a magnetic pull on human thought, whether scientific, literary or artistic, eliciting a cascade of emotional and cultural responses. They inspired wonder—quite literally, in the only recorded response to a Neanderthal skull from Charles Darwin—and a desire to connect across tens and hundreds of millennia. But they also caused deep anxiety, because of what happened to them: extinction. The realization of the Neanderthals’ existence challenged our central metaphysical place in the cosmos. It drastically stretched our frame of reference, much like the development of deep-sky astronomy.

By the early eighteenth century, astronomers had already absorbed the fact that the Sun, rather than an exceptional entity, was ‘just’ the closest star to Earth. Around a century later, when the largest-yet telescope focused on fuzzy clouds beyond the visible stars, another alarming scale-shift occurred: farther off than the constellations of our own Milky Way, the heavens held yet more galaxies, downy with stars. And so, four decades after the first Neanderthal discovery in 1856, people were fizzing with ideas not only about life on the moon and Mars, but on planets circling other stars. Those speculations, both serious and fantasy, have since continued to build on each other. As we began to grasp the dizzying diversity of organisms on our own heavenly sphere, the staggering vista of potential life on worlds with different conditions of gravity, chemistry, pressure and temperature rapidly became vertiginous with possibility.

Researchers have since come up with a number of ways to detect simple alien life based on biosignatures—essentially, observable signs like tell-tale chemicals that point to living creatures processing energy or reproducing. Finding smart aliens might in fact be easier, because if they have a material culture, then we enter the realm of potential technosignatures: the manifestation of technology via perceptible, intentional manipulations of matter and energy. This could be in the form of radiation unexplainable via known astral processes, or tangible objects. The largest telescope within current feasible technological capability could exploit how gravity of the Sun can bend space itself, forming a gigantic magnifying lens, potentially letting us see the surface of an exoplanet, and any ETI (Extraterrestrial Intelligence)-made megastructures.

Searching for and analyzing bio- and techno-signatures is, of course, precisely how archaeologists like myself investigate the ancient human past, though we are separated from our subjects not by space, but time. We might excavate the ashy layers of a 100,000-year-old hearth, measure its temperature, analyze the fuels burned, but we cannot feel the heat of its flames on our faces. In this way, archaeologists, astrobiologists, and ETI researchers are all fundamentally trying to reach beyond the here and now: to map, describe, reconstruct and, in a real sense, experience other worlds of the 4th dimension, and the beings who lived there.

Thinking about how to detect technosignatures, whether across interstellar distances or in archaeological sites on Earth, brings us back to first principles, and the question: what is technology, and why is it? Technology allows two things: ever-more powerful and complicated ways to alter materials, and a means to store information. Ultimately, one key aspect of intelligence is about the intentional manipulation of the surrounding world or environment, in a way that goes beyond immediate survival. It’s the manifestation of some level of consciousness. Archaeologists study the emergence of technology, but while we may draw on theories of anthropology based on our own species, with Neanderthals we can’t assume we’re dealing with evidence of minds all too similar to ours.

Thinking in this way is proving useful for SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), too. And so, in 2018, I was invited to take part in workshops with the Breakthrough Listen project, with anthropologists and ETI experts thrashing out ideas about what technosignatures mean, the ways in which they might appear, and how humans might deal with a situation where we actually make contact. Even in the absence of some sort of direct encounter, technosignatures can still tell us about more than just their makers’ cleverness. Artifacts are the embodiment of ideas. A silver fork implies solid foods, a particular notion of eating and a value system including rare, processed metals; an alien signal implies a transmitter, implies a desire to communicate, implies an understanding of relationality between entities. The challenge will be making sense of these discoveries.

At least in our world, technology and artifacts have implications far beyond mere functionality. Creativity remains one of the essential benchmarks for how we think about ourselves as humans. Accordingly, one of the most common questions people have about Neanderthals is whether they made art. Answering that is always tricky because it’s necessary first to parse what exactly we mean by “art.” Almost all the time, the person asking is thinking of visual art, and often something akin to the layered lions and horses heads painted on the walls of Chauvet cave, or the carved female figurines scattered across western Eurasia.

No objects like this have ever been excavated from any Neanderthal site, but there is evidence of an aesthetic engagement with materials. Neanderthals altered surfaces by incising them, and used colorful substances like mineral pigment. They left behind other more ambitious projects, like the giant rings of stalagmite fragments discovered in a deep cave in France. This site, called Bruniquel, is so primal and yet weirdly beautiful it could come from any era. In its simplicity, it’s also something we might imagine stumbling upon in a cave on Mars. In this case, the pattern-recognition system represented by our eyes and brain would be the technosignature detection software. Thinking through the ways we identify aesthetic material engagements in Neanderthals and other hominins therefore has real significance for how we deal with the idea of an ETI signal that contains scant obvious symbolic content, or even none that we can recognize.

The notion of contact is based on the assumption that communication is possible. Humans communicate with each other using a multiplicity of media: by sound or movement, light or texture. What these all share, however, are underlying commonly-understood meanings, whether expressed with a character that is easily traceable to what is being referenced, or via symbols that require decoding. While it’s been possible to discover, investigate, and sometimes decode ancient communication systems like Mayan hieroglyphs, the farther back we go in time, the more difficult it is to reconstruct or even assess the presence of language. That’s because, aside from the added complication of script changes, sound in human speech alters far faster than meaning. (Sometimes you can trace the mutations. For example, the English word brother and the French frère derive from the Sanskrit bhrātr and the Latin frāter, respectively.)

Even the most ancient potential shared word roots only go back a few thousand years. Deeper into prehistory, beyond any written texts, we face a linguistic abyss. This gives us some idea of the conundrum we might face with an extraterrestrial signal, where there is no contextual data at all from which to reconstruct meaning. The question of whether Neanderthals talked is therefore of relevance for approaching SETI. Anatomically, there’s very good evidence that Neanderthals were both capable of making sounds a lot like ours, and also that their hearing was tuned into the same frequencies of speech. However, precisely how they spoke and what they spoke about remains unknowable.

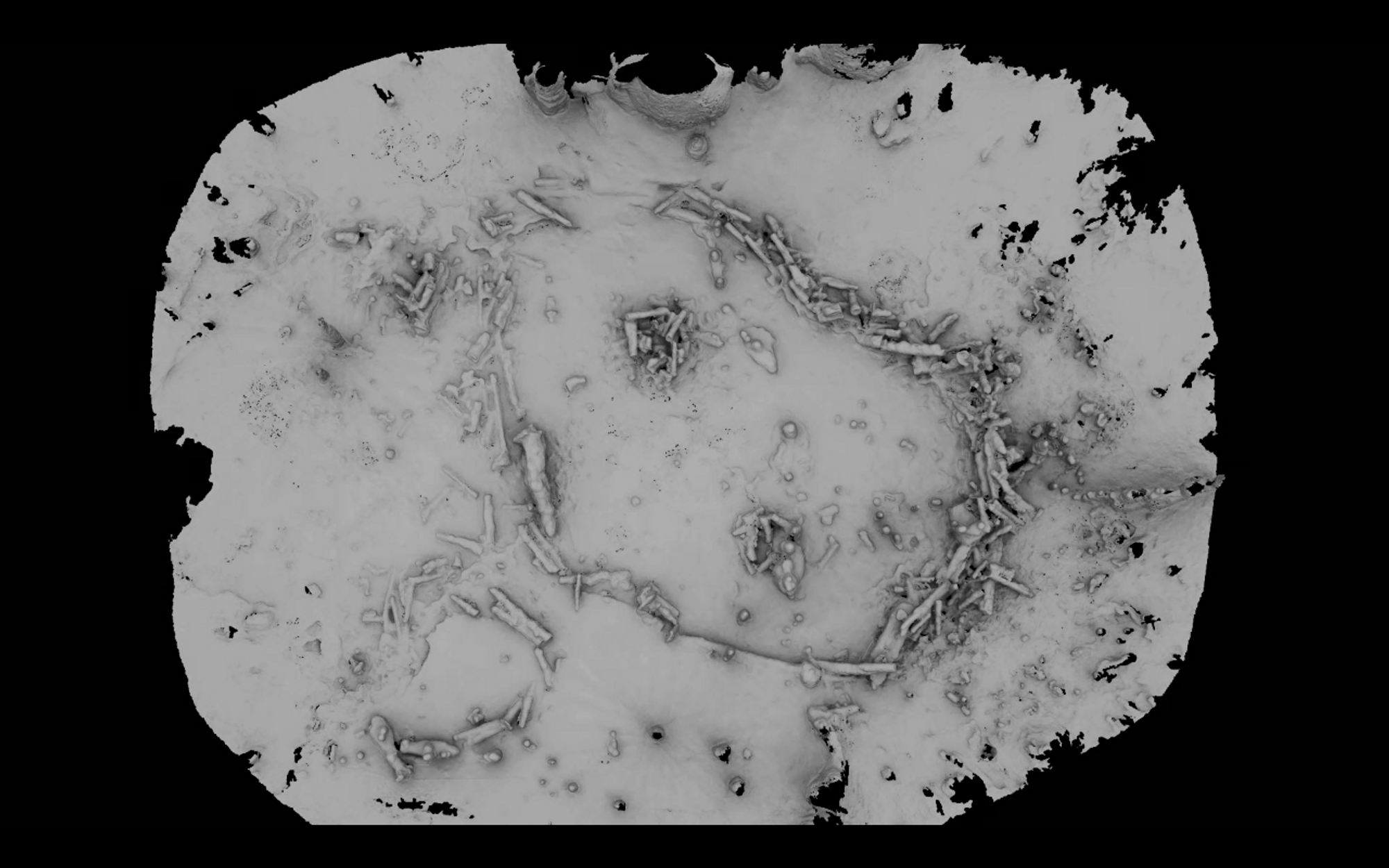

If we do ever detect a technosignature, it is entirely possible that its makers could be long dead, or that the culture, species, or even total planetary biota from which it sprang are extinct. Theoretical considerations of SETI require estimating the longevity of technology and cultures; we are certainly talking about timescales covering at least thousands, if not millions, of years (also taking lightyears into account, the space separating a signal from its source). While the origin of the signals might be technically “derelict,” ruined traces of the hardware might survive. Here, too, there are archaeological correlations: we can only see the barest outlines of an open-air Neanderthal campsite at the site of La Folie, France, marked by a circle of postholes enclosing scattered debris inside. But sometimes, when excavated, the edges of their stone tools are still sharp enough to cut a human hand.

Whether we are talking about intelligence in Neanderthals or ETI, we tend to focus on things like processing or memory in a computing sense, the ability to manipulate matter in complicated ways, and to connect ideas and make leaps of inference. Less attention is paid to emotional intelligence as a metric of adaptive importance. Humans have immense capacity for empathy on an individual basis and can demonstrate extraordinary levels of compassion and altruism at societal levels. Yet as a species, though we are exceptionally good at creatively using materials, extracting energy, distributing labor, and manufacturing a profusion of choice and stuff, we aren’t so great at doing all this in a truly equitable or sustainable manner. Most strikingly, notions of competition and exploitation for resources as the basis for “civilization” end up being projected onto other species, both non-human and ETI, as the definition of evolutionary success.

For example, discussion about Neanderthal subsistence has often involved comparing it to that of Homo sapiens, in order to look for evidence of dietary underachievement. This assumes that the Neanderthals’ disappearance was caused, or hastened in some way, by their own incompetence. Archaeological discoveries several decades ago undermined once-popular theories that Neanderthals were scavengers rather than top hunters. Those ideas were soon replaced by suggestions that they were incapable of fully exploiting their environments by eating seafood, small game, or plants. Today, we know that they were capable of all of this, and on occasion even appear to have over-indulged in some easily-available foods like tortoise. Nevertheless, the sense that being a successful hominin means capitalizing on resources, rather than using them “lightly” and sustainably, has persisted. This idea, that ultra-exploitation is a natural outgrowth of evolved intelligences, is echoed in some early technosignature theories of how ETI harvest energy.

Proposed in the mid-1960s, the Kardashev scale presents quite mind-boggling definitions of alien technological development. It held that the first stage of this definition of “civilization” here on Earth, or Type I, would be achieved once we were using all available energy, from solar, tide, wind, geothermal, nuclear, fossil fuels, and anything else. Type III, the most advanced “civilization” predicted by this scale, envisions a culture that has managed to gather the energy from the majority of stars in its entire galaxy. This means enclosing celestial bodies in gigantic spheres, which would dramatically alter the way such galaxies appear to distant observers, making them glow in infrared. In theory, this should be a relatively straightforward way to work out whether vast, smart ETIs exist. Using astronomical data already collected, searches for signatures potentially suggestive of Type III engineering have been undertaken, but so far reveal very little, even of possibilities. A new study examining over 16,000 sources found just two galaxies with an unusual infrared emission worth investigating further.

It follows that these Type III cultures must be extremely rare. But why? In 1961, the likelihood of ETI existence was quantified by the Drake Equation: if the physics and chemistry which led to life on Earth are universal, then it seems likely that they are out there. This led to the Fermi Paradox: if ETI likely exists, why the lacuna in confirmed evidence? The timely explanation—based on our experiences of the nuclear age—was that perhaps massive technological development inevitably led civilizations to self-destruction. Another, more nuanced answer followed, based on something termed the Inevitable Expansion Fallacy. Somewhere along the line, it might become obvious to ETIs—as it is dawning on us—that rampant development is not the most adaptive choice, if it means maxing out every available resource at the cost of sustainability or quality of life. Instead, they might choose another path. In other words, the dominant, and decidedly capitalist, conceptualization of Earth’s techno-civilization may be hampering our search for other lifeforms.

What if we did meet aliens? Science fiction often imagines such an encounter as innately hostile; either they mistreat us, or we mistreat them. In the latter scenario, they invariably fall victim to our scientific curiosity. We reduce them to specimens for testing, rather than an opportunity for new relations and exchange. There are echoes here too in debates over the future of Neanderthal research. Genetic engineering is allowing us to examine, through small agglomerations of cells, how Neanderthal-specific genes alter very early brain development and connectivity. The results are admittedly intriguing, showing clear differences, but there is an unaddressed ethical question. At what point do we stop such research? How large and diversified should we allow these Neanderoid cerebral blobs to get? What about connecting them to sensory inputs? Or splicing bits into living creatures, from mice to primates? What if some rogue lab attempts a de-extinction, using a Neanderthal genome in an ape or human fetus, as is being pursued for mammoths? We should consider carefully where giving free rein to cold curiosity, rather than empathy, could take us.

Thinking about the ways we approach studying both Neanderthals and any potential ETI from a moral and ethical point of view forces us to consider deeper questions about who we are as a species, and who we want to be. Pasts, present, and futures are connected, and even though archaeology and astronomy more broadly lead us to confront the temporality of existence, our perspective on cosmological scales tends to be extremely myopic. We can just about comprehend centennial time, envisioning the handful of generations separating us from the Renaissance. Move beyond that and we struggle. Millennial timescales become fuzzy, while thinking across spans that saw the vanishing of entire other forms of humanity—Neanderthals, Denisovans, the Flores “Hobbits”—is solidly beyond our imagination.

The prospect of annihilation is especially difficult to process. The ever-present specter of extinction that hangs over Neanderthals is a reminder of the ephemerality of existence. The few hundred thousand years they were around is small beer within deep time palaeontology, and even the much-discussed claim that Homo sapiens’ presence and significant impact on Earth merits the naming of a new geological epoch—the Anthropocene—fades somewhat when looked at over properly ancient time. In fact, it was the long durée viewpoint of astrobiology that led some researchers to seriously consider the possibility that an intelligent species arose and developed an industrialized lifeway at some past point in Earth’s history.

While the evidence was not convincing, the intellectual exercise did reveal something sobering. Even if some humans eventually leave this planet for other cosmic shores, what remains of us here when passed through the wringer of 10s or even 100s of millions of future years—and the inevitable continental shuffling and tectonic ructions—will be little more than geological perfume. The entirety of hominin material existence will on average be reduced to a rock layer of less than a hand’s breadth. Aside from freakishly rare preservation of fossils or objects, our presence will only be traceable through relative amounts of chemical biomarkers and elemental isotopes, unusual molecular patterning, rare metal abundance, and possibly nano-scale plastics and synthetics.

Far-future ponderings on Earth’s mid-life “human phase” seem to be pulled out of us by Neanderthals, even from the earliest days of their discovery. Through a mashup of evolutionary ideas, palaeontology and deep time, the latter nineteenth century gave rise to new visions of the future, and what it means to survive. In 1885, a largely-forgotten intellectual English clergyman named Bourchier Wrey Savile published a treatise against evolution and natural selection. Its content initially appears fairly unremarkable, but its title is striking: The Neanderthal skull on evolution, in an address supposed to be delivered A.D. 2085, with three illustrations. After an extraordinarily long preface, Wrey Savile then has the skull itself narrate while onstage in an imagined future soiree at St James’s Hall in Piccadilly, contemporary London’s principal concert venue. Less than a decade later, the more-celebrated mind of H.G. Wells was imagining in 1893 what humans would look like in a million years’ time.

Today, 2085 AD does not sound so very distant, and our fantasies about the future have metamorphosed. One persistent notion found in science fiction consists of a post-human future, where various interfaces between consciousness and cyber data will allow us to transcend our meat sack, or embodied existence. In a real sense, Neanderthals have already ascended in this way. Rather than ceasing entirely to exist, their DNA still walks the Earth—in varying proportions and configurations—within you and me. When all that is left of a species is the blood running through the veins of another, is that extinction or survival?

Perhaps the greatest gift the Neanderthals bequeathed us—beyond genetic upgrades and perhaps even technological or cultural know-how—is the opportunity for self-reflection. What makes us different, and what do we share? In what ways do they influence what we mean by “human”? And how do societies react when scientific discovery puts a damper on their narrative of exceptionalism? One of the most fundamental lessons from recent decades in human origins research is that there is no neat narrative where Homo sapiens’ inherent superiority guaranteed our survival. Plenty of those pioneer populations that made their way into Eurasia went extinct. Perhaps rather than disparaging Neanderthals for not domesticating the reindeer they hunted, making metal bifaces, or building skyscrapers, we need to take a hard look at what we define as success in ourselves. Is our legacy we are on track for as a species one of massive, metastasized levels of material production and consumption, or of species-level collaboration built on empathy and altruism?

Being the last surviving hominin is not a victory, but rather a story of serendipity. Facing an uncertain future, it’s time to accept that perhaps we didn’t outlive the Neanderthals because of our capacity for cleverness or coercion, but thanks to our knack for conviviality, cooperation, and compassion. We can only hope that we share these attributes with lifeforms from worlds elsewhere, and that contact, whenever that happens, will be based on cordial curiosity, not fear and domination. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast