Color the Mind: 24 Hours of Ragas, Live!

The first Ragas Live Festival took place during 2012's summer solstice. Broadcast live from Columbia University's radio station WKCR, the twenty-four-hour marathon of Indian classical music was an immediate success and helped unleash New York's raga renaissance.

"After I returned from Calcutta," recalls Ragas Live executive producer David Ellenbogen, "I was the only guy with a radio show who was deeply into Indian classical music, so I invited anybody who played Indian classical instruments into WKCR's studio. Within a year, the gurus of all these people coming on the show were saying, 'Why are they on the show and not me?' So pretty soon I had all these maestros like [slide guitarist] Vishwa Mohan Bhatt and [sitarist] Shahid Parvez, amazing stars.

"Finally, this clever undergrad named Ahmet Ali Arslan said, 'Why don't you do this for twenty-four hours?' Everybody loved the idea. There were fifty musicians the first year and I think my budget was maybe $30, for chai and samosas. Six months later, people started calling me about next year's festival. We did it at WKCR for four more years, but we all knew it was destined to become a live event."

The first two performers at the first Ragas Live Festival happened to be sitarist Neel Murgai and the tabla duo of Sameer Gupta and Ehren Hanson. At the time, Murgai and Gupta were hosting weekly Indian jam sessions in a Brooklyn club. This was the gestation stage of what would officially become, in 2015, the Brooklyn Raga Massive, New York's democratically inclined and fusion friendly grass-roots answer to India's cool but corporate Coke Studio TV phenomenon.

With Ellenbogen now a guitar-playing member of the collective, BRM partnered with Ragas Live in 2013 for another in-studio marathon that drew a star in sitarist Krishna Bhatt, a teacher/guru to some massive members. Bhatt's appearance lent credibility to Ellenbogen's effort, and he's back for this year's online festival.

A Jaipur-raised member of an esteemed musical family that included uncle Vishwa Bhatt, Krishnaji found a guru in Ravi Shankar and, like the world's most famous Indian classical musician, performed both exquisite classical music while making syncretic forays into rock and jazz, in California. In the BRM, Krishnaji discovered a young generation of desi and American musicians unbound by the constraints of either the guru–shishya (mentor-protégé) or centuries-old gharana traditions of lineage and apprenticeship. These musicians performed Indian music of a specific style, or tempo, such as the slow and stately dhrupad genre.

"There's no purity of gharanas anymore, because people travel," Bhatt says. "We hear music from around the world, and there's so much beauty everywhere, it's hard not to be influenced." The BRM has definitely raised the profile of Indian music among younger local listeners, he says, noting that while Indian classical events were happening in the New York area when BRM came along, they were smaller in ambition and less frequent than the Massive's "broad-minded and collaborative" weekly events.

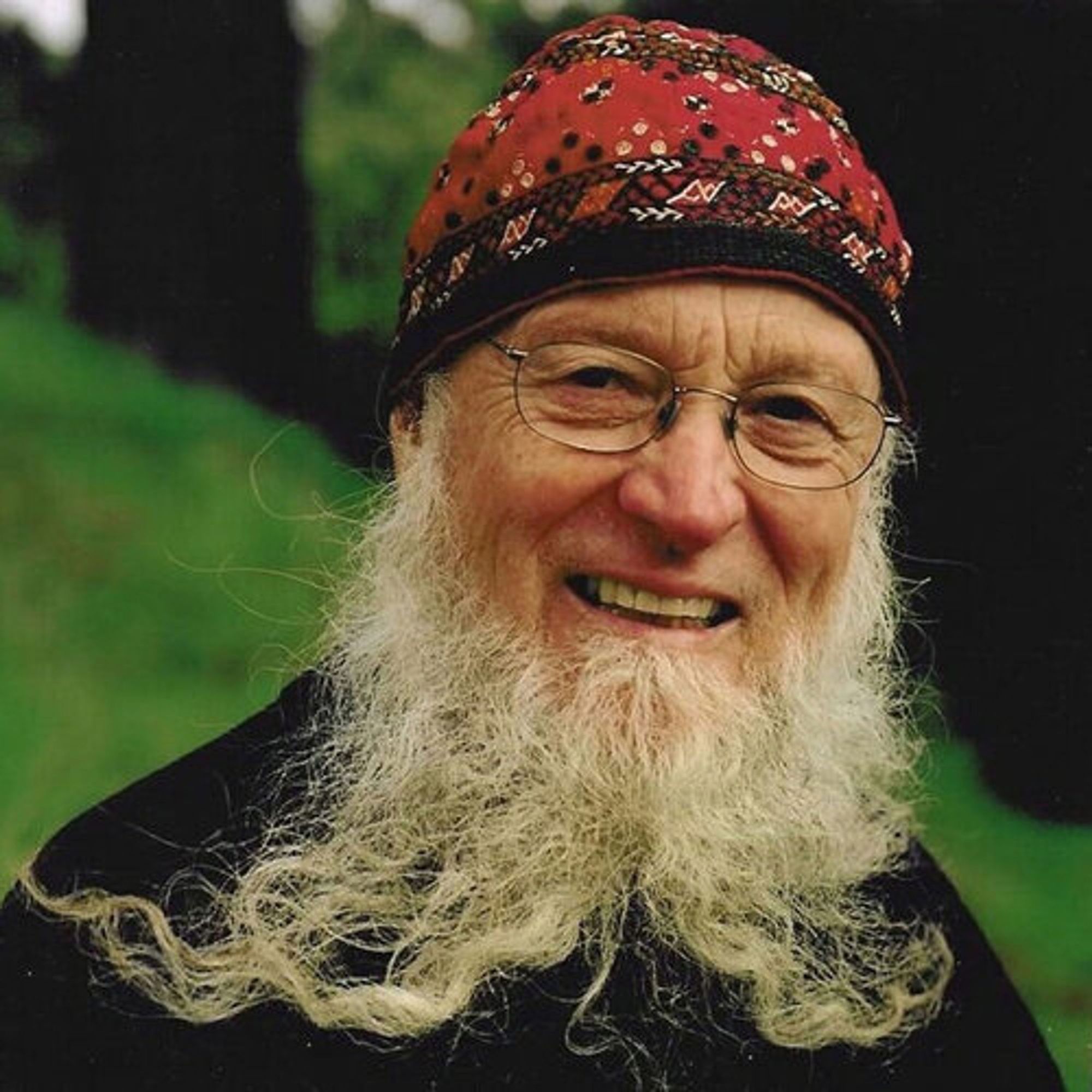

Ellenbogen began adding music from other cultures to the Ragas Live mix. African musicians and a chamber ensemble had become part of the mix by 2016, when the festival moved to Pioneer Works and where it has remained. Subsequent highlights have included a symphonic-scale collaboration with Adam Rudolph's Go: Organic Orchestra, a memorable tribute illuminating John Coltrane's raga-like tetrachordal explorations, and the New York premiere of BRM's Terry Riley tribute, In D. The latter will also serve as the penultimate performance at this year's online iteration and will be followed by a rare set of solo raga improvisations by the eighty-five-year-old Minimalist master himself.

This year's online iteration explodes with sounds from around the globe. The virtual context afforded Ellenbogen and art director Adrian Tillman the freedom to explore the world in search of music that would resonate with that of India. With ninety musicians in thirteen cities, it challenged the pair to do justice to the music visually as well. "It's the equivalent of producing twenty-four albums and twenty-four movies in fourteen cities," Ellenbogen says.

"One of the cool things about this festival," he adds, "is that, alongside classical artists, we're presenting a lot of South Asian musicians who represent the folk core of this music but wouldn't necessarily show up at an Indian classical-music festival." These include the Womanly Voices and Dhun Dhora from Rajasthan; Prince Nepali, an esteemed sarangi player from Nepal; and Parvathy Baul, a singer, dancer, and storyteller immersed in the mystical Sufi tradition of the West Bengal Bauls. "For the first time, you can see an amazing group of musicians in their own environments. It's a step deeper than being in a darkened theater," Ellenbogen says.

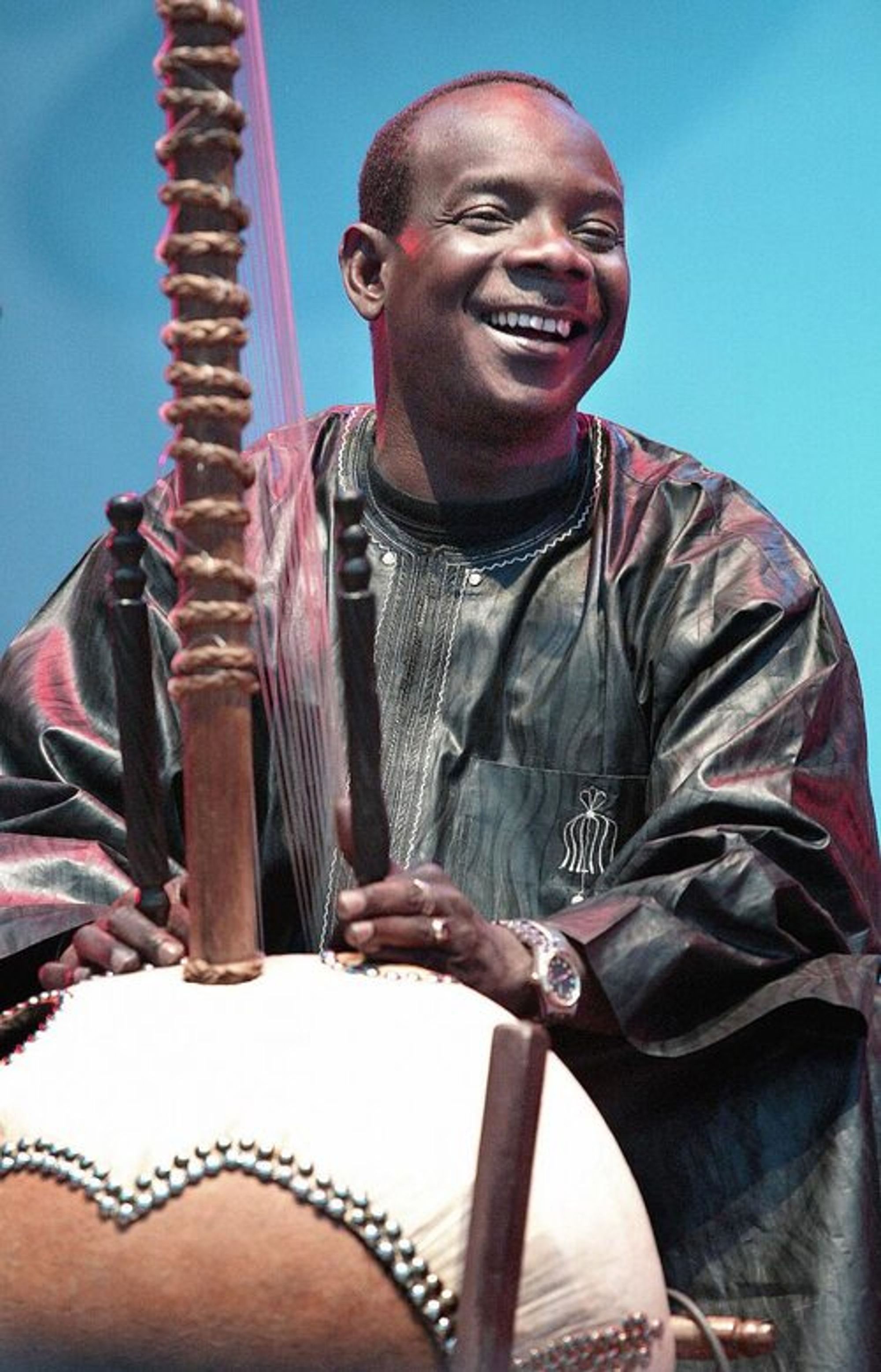

The renowned Mali kora master Toumani Diabate, Mali-immersed classical guitarist Derek Gripper, and Madagascar trio Toko Telo are on board for this virtual global tour. And of course so are Brooklyn Raga Massive all-stars like Jay Gandhi (bansuri), Arun Ramamurthy (violin), and vocalist Samarth Nagarkar.

Like many Western listeners, my gateway drug to the Indian classical hard stuff was rock. Pandit Ravi Shankar, working the post-Woodstock festival circuit, blew my mind for the first time at the ill-fated 1970 Portland Music & Art Fair, where he was one of only a few advertised name acts to actually show up and perform. (Delaney and Bonnie, you owe me!) However, I imagine many more afficionados found their way to India through the minimalists. Riley, Henry Flynt, and La Monte Young studied with Hindustani (North Indian) vocalist Pandit Pran Nath in New York during the 1970s, while Philip Glass studied and collaborated with Ravi Shankar.

Indian classical's appeal to the minimalists probably began with the harmonic drones produced on the tanbura, the humble stringed instrument whose mesmerizing overtones accompany nearly all Indian classical music. Essentially a tonal framework, a raga is introduced in a slow, non-metered, and unaccompanied section known as the alap. Thena percussionist, playing either tabla or a South Indian percussion instrument, organizes and embellishes a raga's cyclic structure, or tala. A singer or instrumentalist— performing on sitar, sarod, bansuri flute, or something else—improvises virtuosically over the five to seven ascending and then descending notes that define a raga—and that's where rock fans tended to tune in.

Indian music embodies great complexity while striving to convey a specific rasaSanskrit for juice, essence, flavor, or mood. Indeed, "the same artist can play the same raga ten times, and each one will have a different mood," Bhatt says, "which is so mysterious and beautiful." The various rasas embody love, laughter, fury, compassion, disgust, and sorrow, among other contemplative states. "A raga can relate to all those things," Bhatt says. "It connects to all aspects of human beings and is close to the heart."

Or as the Sanskrit sage Bharata Sastra observed a couple of thousand years ago in the pages of the Natya Sastra: "Just as noble-minded persons enjoying delicious food seasoned with different spices relish the taste with delight, so does the knowing audience relish and savour the experience of emotional states in a performance and are moved by them." Indian music is synesthetic; ragas "color the mind."

Among the hundreds of known ragas, only several dozen classics enjoy serious play. And since every raga is associated with a specific time of day, evening ragas obviously have a higher profile than morning and afternoon ragas. My friends in improv-rock fandom like to say "never miss a Sunday show," which may have its Indian correlate in "never miss a morning raga." Thus is the beauty of overnight festivals like Ragas Live, which provides a long-form musical experience not unlike India's venerable festival tradition.

Although the Hindustani music of North India enjoys a somewhat higher profile outside of South Asia, Southern India's Carnatic tradition is equally important. Krishna Bhatt (accompanied by tablist Mir Naqibul Islam) will in fact perform raga Charukesi, one of "ten to twenty" Carnatic ragas that have become a strong part of northern tradition. "The first half of the scale is natural and the sixth and seventh notes are flat," he explains. "It's a very romantic, devotional, and beautiful scale, and many musicians have interpreted and composed around it."

California-born Carnatic singer Roopa Mahadevan has made several Ragas Live appearances and embodies its classics-plus-crossover credo. "Carnatic music is distinguished by its dynamism," she says. "A given melodic shape will have a particular pacing to it, but that pacing will change even within a phrase. The raga's personality comes from these different shapes interacting with each other to paint a picture. Even the speed with which you oscillate a note becomes critical to the raga's identity. Carnatic compositions have lines that repeat several times, each time with a different variation that's part of the composition. And then you improvise on top of that. You need to learn and internalize a lot of stuff."

This year she will deliver a traditional Carnatic set as the "avatar" she calls Roopa and Six Yards. Why six yards? "A sari is six yards of cloth," she says. "Dressing up in a sari for a concert gets me in the right frame of mind. Wearing this heavy cloth is an intentional act. The sari enhances the ritual by evoking something outside of yourself with which you merge. I've been experimenting with keeping my hair out, though, because girls tying up their hair so as not to appear brazen is just gender crap," she laughs. "I'm all for mini-revolutions here and there. You can be a classical musician and still have a good time and enjoy yourself onstage. You can be human."

Mahadevan calls her other avatar Roopa in Flux. It's a genre-defying hybrid of her Carnatic sensibilities mixed with Hindustani, jazz, and the Middle Eastern maqam tradition she will explore during Ragas Live as part of trumpeter Amir Elsaffar's Raga Maqam collaboration with BRM. "I think the crossover sound will eventually become more of my identity," Roopa says.

Indian music is justly enjoyed for its transcendental properties, its ability to temporarily transport listeners somewhere outside themselves into ecstatic esthetic realms. Roopa, however, believes there's also plenty of political potential in Carnatic music.

"Carnatic compositions talk about the personal journey and describe escape and reunion with the divine," she says. "It's rare to hear a call to action involving ethical obligations or interdependence with other people. But a conversation with the needs of the day could make it even more interesting. You need rigor, and I respect that. But wouldn't it be cool if there were new compositions that retain the form while talking about the things we talk about now?"

What the musicians I know are talking about, largely, is the work-in-progress nature of online performance technology. Ragas Live offers one solution in its beautifully captured performances. Many musicians, however, bemoan the delays and lags that make online performances involving geographically separated performers so problematic. Not to mention the lack of an audience with which to respond.

Bona-fide Indian music superstar Zakir Hussain, however, finds something special in the sort of classical tabla solo performance he will deliver during Ragas Live. Having played in nearly every conceivable classical configuration, as well as in heavy-duty fusion ensembles such as Shakti, the California-based percussionist offers a Zen-like take on his current situation.

"Reactions among your fellow musicians and the audience set the tone and intensity of a performance," Hussain says. "And we miss that. But when you perform alone, you're more in the position of speaking your mind and sharing your thoughts – rather than sharing one thought and waiting for another musician to develop it, or an audience reaction. In a live setting, you might be able to share one, two, or even three layers of your inner self.

"During a solo virtual concert, however, you have more time to reveal yourself in depth. When I play by myself, I draw upon all the information transmitted to me by my teacher—my father—and from having played with the great masters of Indian music. Putting that forward in as pristine a form as possible is what has been special about virtual concerts for me. It's straight from the heart, spontaneous, without fixes or airbrushing. I'm revealed to the audience without the camouflage of a sitar, sarangi, guitar, or anything else."

What should audiences, especially Western audiences, listen for in a solo tabla concert?

"The one problem an audience might have is following the time, because I don't have a support instrument to hold the time together. If possible, I'll have a sarangi to support my solo performance. If not, the audience will need to focus on how the time signatures move and how the rhythm cycle unfolds, which requires some intense focus.

"Otherwise, my only advice is to sit back and relax—with your headphones on. You'll hear the full depth of the instrument. Close your eyes and focus on that. The visuals are otherwise pretty static. But I'm happy to play—what do you call that?—unplugged. I'm quite happy to share myself in that manner, lay myself bare, and hope for the best."

Subscribe to Broadcast